Abstract

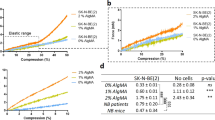

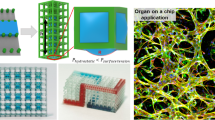

This protocol describes how to build and implement a three-dimensional (3D) cell culture system, TRACER (tissue roll for analysis of cellular environment and response), that enables analysis of cellular behavior and phenotype in hypoxic gradients. TRACER consists of infiltrating cells encapsulated in a hydrogel extracellular matrix (ECM) within a thin strip of porous cellulose scaffolding that is then rolled around an oxygen-impermeable mandrel for assembly of thick and layered 3D tissue constructs that develop cell-defined oxygen gradients. TRACER differs from other stacked-paper cell culture models because it is assembled from a single-piece scaffold, which facilitates rapid disassembly for analysis of different cell populations and metabolites. The protocol describes how to fabricate TRACER components, cell seeding in the scaffold, and scaffold assembly and disassembly. Furthermore, it provides methods to quantify live, dead, or proliferating cells, as well as gradients of oxygen using the nitroimidazole derivative EF5, in a layer-by-layer analysis with confocal microscopy or by flow cytometry of cells isolated from the TRACER scaffold. Additional methods to isolate live cells from TRACER layers for dose–response analysis with a clonogenic assay, as well as steps to extract RNA or fast-changing metabolites from TRACER layers, are also presented. Finally, we provide alternative steps to establish TRACER co-cultures for assessment of tumor cell invasion and metastasis, in this case in the absence of a hypoxic gradient. Although analysis time varies according to the assay chosen, scaffold fabrication and seeding typically take 2 h, and TRACER assembly takes 20 min on the day following scaffold seeding. The TRACER platform is designed for use by researchers and students who have basic tissue culture experience.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bissell, M. J. & Radisky, D. Putting tumours in context. Nat. Rev. Cancer 1, 46–54 (2001).

Xing, Y., Zhao, S., Zhou, B. P. & Mi, J. Metabolic reprogramming of the tumour microenvironment. FEBS J 282, 3892–3898 (2015).

Kumar, R., Kuniyasu, H., Bucana, C. D., Wilson, M. R. & Fidler, I. J. Spatial and temporal expression of angiogenic molecules during tumor growth and progression. Oncol. Res. 10, 301–311 (1998).

Quail, D. F. & Joyce, J. A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Med. 19, 1423–1437 (2013).

McAllister, S. S. & Weinberg, R. A. The tumour-induced systemic environment as a critical regulator of cancer progression and metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 717–727 (2014).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011).

Infanger, D. W., Lynch, M. E. & Fischbach, C. Engineered culture models for studies of tumor-microenvironment interactions. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 15, 29–53 (2013).

Gill, B. J. & West, J. L. Modeling the tumor extracellular matrix: tissue engineering tools repurposed towards new frontiers in cancer biology. J. Biomech. 47, 1969–1978 (2014).

DelNero, P., Song, Y. H. & Fischbach, C. Microengineered tumor models: insights & opportunities from a physical sciences-oncology perspective. Biomed. Microdevices 15, 583–593 (2013).

Rodenhizer, D., Cojocari, D., Wouters, B. G. & McGuigan, A. P. Development of TRACER: tissue roll for analysis of cellular environment and response. Biofabrication 8, 045008 (2016).

Rodenhizer, D. et al. A three-dimensional engineered tumour for spatial snapshot analysis of cell metabolism and phenotype in hypoxic gradients. Nat. Mater. 15, 227–234 (2016).

Derda, R. et al. Multizone paper platform for 3D cell cultures. PLoS ONE 6, e18940 (2011).

Hirschhaeuser, F. et al. Multicellular tumor spheroids: an underestimated tool is catching up again. J. Biotechnol. 148, 3–15 (2010).

Clevers, H. Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell 165, 1586–1597 (2016).

Sachs, N. & Clevers, H. Organoid cultures for the analysis of cancer phenotypes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 24, 68–73 (2014).

Francies, H. E. & Garnett, M. J. What role could organoids play in the personalization of cancer treatment? Pharmacogenomics 16, 1523–1526 (2015).

Dunne, L. W. et al. Human decellularized adipose tissue scaffold as a model for breast cancer cell growth and drug treatments. Biomaterials 35, 4940–4949 (2014).

Nyga, A., Cheema, U. & Loizidou, M. 3D tumour models: novel in vitro approaches to cancer studies. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 5, 239–248 (2011).

Villasante, A. & Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Tissue-engineered models of human tumors for cancer research. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 10, 257–268 (2015).

Charbe, N., McCarron, P. A. & Tambuwala, M. M. Three-dimensional bio-printing: a new frontier in oncology research. World J. Clin. Oncol. 8, 21–36 (2017).

Sung, K. E. et al. Transition to invasion in breast cancer: a microfluidic in vitro model enables examination of spatial and temporal effects. Integr. Biol. 3, 439–450 (2011).

Zervantonakis, I. K. et al. Three-dimensional microfluidic model for tumor cell intravasation and endothelial barrier function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 13515–13520 (2012).

Chen, M. B. et al. On-chip human microvasculature assay for visualization and quantification of tumor cell extravasation dynamics. Nat. Protoc. 12, 865–880 (2017).

Bai, J., Tu, T. Y., Kim, C., Thiery, J. P. & Kamm, R. D. Identification of drugs as single agents or in combination to prevent carcinoma dissemination in a microfluidic 3D environment. Oncotarget 6, 36603–36614 (2015).

Jeon, J. S. et al. Generation of 3D functional microvascular networks with human mesenchymal stem cells in microfluidic systems. Integr. Biol. 6, 555–563 (2014).

Derda, R. et al. Paper-supported 3D cell culture for tissue-based bioassays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18457–18462 (2009).

Young, M. et al. A TRACER 3D co-culture tumour model for head and neck cancer. Biomaterials 164, 54–69 (2018).

Amann, A. et al. Development of an innovative 3D cell culture system to study tumour–stroma interactions in non-small cell lung cancer cells. PLoS ONE 9, e92511 (2014).

Zhang, J. Z. et al. The use of spectroscopic imaging and mapping techniques in the characterisation and study of DLD-1 cell spheroid tumour models. Integr. Biol. 4, 1072–1080 (2012).

Ohnishi, K. et al. Plastic induction of CD133AC133-positive cells in the microenvironment of glioblastoma spheroids. Int. J. Oncol. 45, 581–586 (2014).

van de Wetering, M. et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell 161, 933–945 (2015).

Gao, D. et al. Organoid cultures derived from patients with advanced prostate cancer. Cell 159, 176–187 (2014).

Boj, S. F. et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell 160, 324–338 (2015).

Pradhan, S., Hassani, I., Seeto, W. J. & Lipke, E. A. PEG-fibrinogen hydrogels for three-dimensional breast cancer cell culture. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 105, 236–252 (2017).

Kievit, F. M. et al. Chitosan-alginate 3D scaffolds as a mimic of the glioma tumor microenvironment. Biomaterials 31, 5903–5910 (2010).

Lü, W. D. et al. Development of an acellular tumor extracellular matrix as a three-dimensional scaffold for tumor engineering. PLoS ONE 9, e103672 (2014).

Gill, B. J. et al. A synthetic matrix with independently tunable biochemistry and mechanical properties to study epithelial morphogenesis and EMT in a lung adenocarcinoma model. Cancer Res. 72, 6013–6023 (2012).

Jeon, J. S. et al. Human 3D vascularized organotypic microfluidic assays to study breast cancer cell extravasation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 214–219 (2015).

Ayuso, J. M. et al. Development and characterization of a microfluidic model of the tumour microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 6, 36086 (2016).

Albrengues, J. et al. LIF mediates proinvasive activation of stromal fibroblasts in cancer. Cell Rep. 7, 1664–1678 (2014).

Gaggioli, C. et al. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1392–1400 (2007).

Boyce, M. W., LaBonia, G. J., Hummon, A. B. & Lockett, M. R. Assessing chemotherapeutic effectiveness using a paper-based tumor model. Analyst 142, 2819–2827 (2017).

Zanoni, M. et al. 3D tumor spheroid models for in vitro therapeutic screening: a systematic approach to enhance the biological relevance of data obtained. Sci. Rep. 6, 19103 (2016).

Sirenko, O. et al. High-content assays for characterizing the viability and morphology of 3D cancer spheroid cultures. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 13, 402–414 (2015).

Beaumont, K. A., Anfosso, A., Ahmed, F., Weninger, W. & Haass, N. K. Imaging- and flow cytometry-based analysis of cell position and the cell cycle in 3D melanoma spheroids. J. Vis. Exp. (106), e53486 (2015).

Hubert, C. G. et al. A three-dimensional organoid culture system derived from human glioblastomas recapitulates the hypoxic gradients and cancer stem cell heterogeneity of tumors found in vivo. Cancer Res. 76, 2465–2477 (2016).

Giesbrecht, J. L., Wilson, W. R. & Hill, R. P. Radiobiological studies of cells in multicellular spheroids using a sequential trypsinization technique. Radiat. Res. 86, 368–386 (1981).

Taubenberger, A. V. et al. 3D extracellular matrix interactions modulate tumour cell growth, invasion and angiogenesis in engineered tumour microenvironments. Acta Biomater. 36, 73–85 (2016).

Kim, S. A., Lee, E. K. & Kuh, H. J. Co-culture of 3D tumor spheroids with fibroblasts as a model for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 335, 187–196 (2015).

Ehsan, S. M., Welch-Reardon, K. M., Waterman, M. L., Hughes, C. C. & George, S. C. A three-dimensional in vitro model of tumor cell intravasation. Integr. Biol. 6, 603–610 (2014).

Liu, T., Lin, B. & Qin, J. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts promoted tumor spheroid invasion on a microfluidic 3D co-culture device. Lab Chip 10, 1671–1677 (2010).

Young, M. et al. A TRACER 3D co-culture tumour model for head and neck cancer. Biomaterials 164, 54–69 (2018).

Mosadegh, B. et al. A paper-based invasion assay: assessing chemotaxis of cancer cells in gradients of oxygen. Biomaterials 52, 262–271 (2015).

Camci-Unal, G., Newsome, D., Eustace, B. K. & Whitesides, G. M. Fibroblasts enhance migration of human lung cancer cells in a paper-based coculture system. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 5, 641–647 (2016).

Achilli, T. M., McCalla, S., Meyer, J., Tripathi, A. & Morgan, J. R. Multilayer spheroids to quantify drug uptake and diffusion in 3D. Mol. Pharm. 11, 2071–2081 (2014).

Tung, Y. C. et al. High-throughput 3D spheroid culture and drug testing using a 384 hanging drop array. Analyst 136, 473–478 (2011).

Galateanu, B. et al. Impact of multicellular tumor spheroids as an in vivo-like tumor model on anticancer drug response. Int. J. Oncol. 48, 2295–2302 (2016).

Diniz, F. B. et al. Evaluation of carcass traits and meat characteristics of Guzerat-crossbred bulls. Meat Sci. 112, 58–62 (2016).

Walsh, A. J., Cook, R. S., Sanders, M. E., Arteaga, C. L. & Skala, M. C. Drug response in organoids generated from frozen primary tumor tissues. Sci. Rep. 6, 18889 (2016).

Walsh, A. J., Castellanos, J. A., Nagathihalli, N. S., Merchant, N. B. & Skala, M. C. Optical imaging of drug-induced metabolism changes in murine and human pancreatic cancer organoids reveals heterogeneous drug response. Pancreas 45, 863–869 (2016).

Walsh, A. J. et al. Quantitative optical imaging of primary tumor organoid metabolism predicts drug response in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 74, 5184–5194 (2014).

Raghavan, S. et al. Personalized medicine-based approach to model patterns of chemoresistance and tumor recurrence using ovarian cancer stem cell spheroids. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 6934–6945 (2017).

Ruppen, J. et al. Towards personalized medicine: chemosensitivity assays of patient lung cancer cell spheroids in a perfused microfluidic platform. Lab Chip 15, 3076–3085 (2015).

Grist, S. M., Schmok, J. C., Liu, M. C., Chrostowski, L. & Cheung, K. C. Designing a microfluidic device with integrated ratiometric oxygen sensors for the long-term control and monitoring of chronic and cyclic hypoxia. Sensors 15, 20030–20052 (2015).

Raza, A. et al. Oxygen mapping of melanoma spheroids using small molecule platinum probe and phosphorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Sci. Rep. 7, 10743 (2017).

Grimes, D. R., Kelly, C., Bloch, K. & Partridge, M. A method for estimating the oxygen consumption rate in multicellular tumour spheroids. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20131124 (2014).

Ashton, T. M. et al. The anti-malarial atovaquone increases radiosensitivity by alleviating tumour hypoxia. Nat. Commun. 7, 12308 (2016).

Jain, M. et al. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science 336, 1040–1044 (2012).

Armitage, E. G. et al. Metabolic profiling reveals potential metabolic markers associated with Hypoxia Inducible Factor-mediated signalling in hypoxic cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 15649 (2015).

Gunda, V., Yu, F. & Singh, P. K. Validation of metabolic alterations in microscale cell culture lysates using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC)-tandem mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. PLoS ONE 11, e0154416 (2016).

Rodenhizer, D. et al. A three-dimensional engineered tumour for spatial snapshot analysis of cell metabolism and phenotype in hypoxic gradients. Nat. Mater. 15, 227–234 (2015).

Matsumoto, B. Cell Biological Applications of Confocal Microscopy (Elsevier Science, San Diego, 2003).

Shapiro, H. M. Practical Flow Cytometry 4th Edition (John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2003).

Franken, N. A., Rodermond, H. M., Stap, J., Haveman, J. & van Bree, C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2315–2319 (2006).

Xiao, J. F., Zhou, B. & Ressom, H. W. Metabolite identification and quantitation in LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics. Trends Anal. Chem. 32, 1–14 (2012).

Hoogsteen, I. J. et al. Hypoxia in larynx carcinomas assessed by pimonidazole binding and the value of CA-IX and vascularity as surrogate markers of hypoxia. Eur. J. Cancer 45, 2906–2914 (2009).

Wilson, W. R. & Hay, M. P. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 393–410 (2011).

Koch, C. J. Measurement of absolute oxygen levels in cells and tissues using oxygen sensors and 2-nitroimidazole EF5. Methods Enzymol. 352, 3–31 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank S.-U. Ngo-Trong for filming and editing the video protocols. This work was funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant Accelerator supplement (RGPIN-314056 to A.P.M.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R., T.D., D.C., B.X., and A.P.M. designed the research; D.R., T.D., D.C., and B.X. performed the research; D.R., T.D., B.X., and D.C. analyzed the data; and D.R., T.D., and A.P.M. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

Key references using this protocol

1. Rodenhizer, D. et al. Nat. Mater. 15, 227–234 (2016) https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4482.

2. Rodenhizer, D. et al. Biofabrication 8, 045008 (2016) https://doi.org/10.1088/1758-5090/8/4/045008.

3. Young, M. et al. Biomaterials 164, 54–69 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.01.038.

Supplementary information

Combined Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1–16

Supplementary Video 1

Video showing biocomposite

Supplementary Video 2

Video showing TRACER assembly by rolling (Steps 20–30)

Supplementary Video 3

Video showing TRACER disassembly for general analysis (Steps 31–40)

Supplementary Video 4

Video Showing TRACER disassembly for metabolomics analysis (Step 41K)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodenhizer, D., Dean, T., Xu, B. et al. A three-dimensional engineered heterogeneous tumor model for assessing cellular environment and response. Nat Protoc 13, 1917–1957 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-018-0022-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-018-0022-9

This article is cited by

-

3D Models of Sarcomas: The Next-generation Tool for Personalized Medicine

Phenomics (2023)

-

Natural Killer Cells: the Missing Link in Effective Treatment for High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma

Current Treatment Options in Oncology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.