Abstract

Mechanosensitive ion channels convert mechanical stimuli into a flow of ions. These channels are widely distributed from bacteria to higher plants and humans, and are involved in many crucial physiological processes. Here we show that two members of the OSCA protein family in Arabidopsis thaliana, namely AtOSCA1.1 and AtOSCA3.1, belong to a new class of mechanosensitive ion channels. We solve the structure of the AtOSCA1.1 channel at 3.5-Å resolution and AtOSCA3.1 at 4.8-Å resolution by cryo-electron microscopy. OSCA channels are symmetric dimers that are mediated by cytosolic inter-subunit interactions. Strikingly, they have structural similarity to the mammalian TMEM16 family proteins. Our structural analysis accompanied with electrophysiological studies identifies the ion permeation pathway within each subunit and suggests a conformational change model for activation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The modeled atomic coordinates have been deposited in PDB with accession codes 5YD1 (AtOSCA1.1) and 5Z1F (AtOSCA3.1). In addition, EM maps have been deposited in EMDB with accession codes EMD-6822 (AtOSCA1.1) and EMD-6875 (AtOSCA3.1). All other source data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Booth, I. R. & Blount, P. The MscS and MscL families of mechanosensitive channels act as microbial emergency release valves. J. Bacteriol. 194, 4802–4809 (2012).

Walker, R. G., Willingham, A. T. & Zuker, C. S. A Drosophila mechanosensory transduction channel. Science 287, 2229–2234 (2000).

Yan, Z. et al. Drosophila NOMPC is a mechanotransduction channel subunit for gentle-touch sensation. Nature 493, 221–225 (2013).

Zhang, W., Yan, Z., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. Sound response mediated by the TRP channels NOMPC, NANCHUNG, and INACTIVE in chordotonal organs of Drosophila larvae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13612–13617 (2013).

Lehnert, B. P., Baker, A. E., Gaudry, Q., Chiang, A. S. & Wilson, R. I. Distinct roles of TRP channels in auditory transduction and amplification in Drosophila. Neuron 77, 115–128 (2013).

Maingret, F., Fosset, M., Lesage, F., Lazdunski, M. & Honore, E. TRAAK is a mammalian neuronal mechano-gated K+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1381–1387 (1999).

Wu, J., Lewis, A. H. & Grandl, J. Touch, tension, and transduction—the function and regulation of piezo ion channels. Trends Biochem. Sci. 42, 57–71 (2017).

Basu, D. & Haswell, E. S. Plant mechanosensitive ion channels: an ocean of possibilities. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 40, 43–48 (2017).

Jin, P. et al. Electron cryo-microscopy structure of the mechanotransduction channel NOMPC. Nature 547, 118–122 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Ankyrin repeats convey force to gate the NOMPC mechanotransduction channel. Cell 162, 1391–1403 (2015).

Martinac, B., Adler, J. & Kung, C. Mechanosensitive ion channels of E. coli activated by amphipaths. Nature 348, 261–263 (1990).

Kung, C. A possible unifying principle for mechanosensation. Nature 436, 647–654 (2005).

Perozo, E., Cortes, D. M., Sompornpisut, P., Kloda, A. & Martinac, B. Open channel structure of MscL and the gating mechanism of mechanosensitive channels. Nature 418, 942–948 (2002).

Perozo, E., Kloda, A., Cortes, D. M. & Martinac, B. Physical principles underlying the transduction of bilayer deformation forces during mechanosensitive channel gating. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 696–703 (2002).

Sukharev, S. I., Blount, P., Martinac, B., Blattner, F. R. & Kung, C. A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature 368, 265–268 (1994).

Brohawn, S. G., Campbell, E. B. & MacKinnon, R. Physical mechanism for gating and mechanosensitivity of the human TRAAK K+ channel. Nature 516, 126–130 (2014).

Brohawn, S. G., Su, Z. & MacKinnon, R. Mechanosensitivity is mediated directly by the lipid membrane in TRAAK and TREK1 K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3614–3619 (2014).

Syeda, R. et al. Piezo1 channels are inherently mechanosensitive. Cell Rep. 17, 1739–1746 (2016).

Cox, C. D. et al. Removal of the mechanoprotective influence of the cytoskeleton reveals PIEZO1 is gated by bilayer tension. Nat. Commun. 7, 10366 (2016).

Osakabe, Y., Osakabe, K., Shinozaki, K. & Tran, L. S. Response of plants to water stress. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 86 (2014).

Yuan, F. et al. OSCA1 mediates osmotic-stress-evoked Ca2+ increases vital for osmosensing in Arabidopsis. Nature 514, 367–371 (2014).

Hou, C. et al. DUF221 proteins are a family of osmosensitive calcium-permeable cation channels conserved across eukaryotes. Cell Res. 24, 632–635 (2014).

Vasquez, R. J., Howell, B., Yvon, A. M., Wadsworth, P. & Cassimeris, L. Nanomolar concentrations of nocodazole alter microtubule dynamic instability in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 973–985 (1997).

Kiyosue, T., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. Cloning of cDNAs for genes that are early-responsive to dehydration stress (ERDs) in Arabidopsis thaliana L.: identification of three ERDs as HSP cognate genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 25, 791–798 (1994).

Kawate, T. & Gouaux, E. Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography for precrystallization screening of integral membrane proteins. Structure 14, 673–681 (2006).

Guo, J. et al. Structure of the voltage-gated two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 531, 196–201 (2016).

Kintzer, A. F. & Stroud, R. M. Structure, inhibition and regulation of two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 531, 258–262 (2016).

Holm, L. & Rosenstrom, P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 (2010).

Caputo, A. et al. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science 322, 590–594 (2008).

Schroeder, B. C., Cheng, T., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell 134, 1019–1029 (2008).

Yang, Y. D. et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 455, 1210–1215 (2008).

Dang, S. et al. Cryo-EM structures of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel. Nature 552, 426–429 (2017).

Paulino, C., Kalienkova, V., Lam, A. K. M., Neldner, Y. & Dutzler, R. Activation mechanism of the calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A revealed by cryo-EM. Nature 552, 421–425 (2017).

Jeng, G., Aggarwal, M., Yu, W. P. & Chen, T. Y. Independent activation of distinct pores in dimeric TMEM16A channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 148, 393–404 (2016).

Lim, N. K., Lam, A. K. & Dutzler, R. Independent activation of ion conduction pores in the double-barreled calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A. J. Gen. Physiol. 148, 375–392 (2016).

Paulino, C. et al. Structural basis for anion conduction in the calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A. eLife 6, e26232 (2017).

Peters, C. J. et al. Four basic residues critical for the ion selectivity and pore blocker sensitivity of TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3547–3552 (2015).

Duszyk, M., French, A. S. & Man, S. F. The 20-pS chloride channel of the human airway epithelium. Biophys. J. 57, 223–230 (1990).

Haswell, E. S., Phillips, R. & Rees, D. C. Mechanosensitive channels: what can they do and how do they do it? Structure 19, 1356–1369 (2011).

Goehring, A. et al. Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2574–2585 (2014).

Doerner, J. F., Febvay, S. & Clapham, D. E. Controlled delivery of bioactive molecules into live cells using the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nat. Commun. 3, 990 (2012).

Mansouri, M. et al. Highly efficient baculovirus-mediated multigene delivery in primary cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 11529 (2016).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Zhang, K. Gctf: real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016).

Kimanius, D., Forsberg, B. O., Scheres, S. H. & Lindahl, E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. eLife 5, e18722 (2016).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy 135, 24–35 (2013).

Kucukelbir, A., Sigworth, F. J. & Tagare, H. D. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat. Methods 11, 63–65 (2014).

Zhou, N., Wang, H. & Wang, J. EMBuilder: a template matching-based automatic model-building program for high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy maps. Sci. Rep. 7, 2664 (2017).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Nicholls, R. A., Long, F. & Murshudov, G. N. Low-resolution refinement tools in REFMAC5. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 404–417 (2012).

Biasini, M. et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W252–W258 (2014).

Smart, O. S., Neduvelil, J. G., Wang, X., Wallace, B. A. & Sansom, M. S. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 354–360 (1996).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2, 19–25 (2015).

Marrink, S. J., Risselada, H. J., Yefimov, S., Tieleman, D. P. & De Vries, A. H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 7812–7824 (2007).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Berendsen, C. et al. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Wassenaar, T. A., Pluhackova, K., Böckmann, R. A., Marrink, S. J. & Tieleman, D. P. Going backward: a flexible geometric approach to reverse transformation from coarse grained to atomistic models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 676–690 (2014).

Šali, A. & Blundell, T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 (1993).

Lindorff-Larsen, K. et al. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 78, 1950–1958 (2010).

Jämbeck, J. P. M. & Lyubartsev, A. P. An extension and further validation of an all-atomistic force field for biological membranes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2938–2948 (2012).

Jämbeck, J. P. M. & Lyubartsev, A. P. Derivation and systematic validation of a refined all-atom force field for phosphatidylcholine lipids. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 3164–3179 (2012).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: an Nlog(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993).

Bussi, G. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Nosé, S. & Klein, M. L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics for molecular systems. Mol. Phys. 50, 1055–1076 (1983).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the Chen laboratory members for support, especially M. Wang and Y. Niu for help with manuscript preparation, and D. Ding, W. Guo, Q. Tang, and S. Qiu for help with EM data collection. We thank C. Zhang for sharing electrophysiology equipments, S. Zhong at Peking University for providing Arabidopsis thaliana total cDNA, and D. Ren at the Department of Biology, University of Pennsylvania for providing mouse TPC1 cDNA. Cryo-EM data collection was supported by the National Center for Protein Science (Shanghai) with the assistance of L. Kong and Z. Fu, the Center for Biological Imaging, the Electron Microscopy Laboratory and Cryo-EM platform of Peking University with the assistance of X. Li and the Center for Biological Imaging, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Science with the assistance of Z. Guo. Part of the structural computation and molecular dynamics simulation was performed on the High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University and the Computing Platform of the Center for Life Science, Peking University. The work is supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (National Key R&D Program of China, grant no. 2016YFA0502004 to L.C., grant no. 2016YFA0500401 to C.S., grant nos. 2017YFA0103900 and 2016YFA0502800 to Z.Y.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31622021 and 31521062 to L.C., grant no. 31571083 to Z.Y.), the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar of Shanghai, grant no. TP2014008 to Z.Y.), the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (grant no. 14QA1400800 to Z.Y.), the Young Thousand Talents Program of China to L.C., C.S., and Z.Y., and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant nos. 2016M600856 and 2017T100014 to J.-X.W.). J.-X.W. is supported by the Peking University Boya Postdoctoral Fellowship and the postdoctoral foundation of the Peking-Tsinghua Center for Life Sciences, Peking University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. and L.C. conceived the project. Z.Y., C.S., and L.C. designed experiments. M.Z., C.P., and Z.Y. performed electrophysiology experiments. M.Z., J.-X.W., F.Y., and L.C. performed mutagenesis and FSEC experiments. Y.K. and J.-X.W. performed the calcium imaging experiments. D.W. and C.S. performed molecular dynamics simulations. M.Z. prepared the cryo-EM sample. M.Z., J.-X.W., Y.K., and L.C. collected cryo-EM data. M.Z. and L.C. performed image processing and analyzed EM data. L.C. built the model and wrote the manuscript draft. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Integrated supplementary information

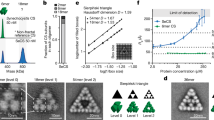

Supplementary Figure 1 Characterization of the AtOSCA1.1 channel.

a, Calcium imaging of AtOSCA1.1-transfected FreeStyle 293-F cells. Hyperosmolality (650 mm sorbitol, denoted as an arrow) triggers a [Ca2+]i increase in FreeStyle 293-F cells expressing AtOSCA1.1-GFP or GFP. [Ca2+]i was monitored by Rhod2 fluorescence (ΔF/F0); data are mean ± s.e.m. (n = 20). n stands for the number of independent cells. The experiments were repeated three times and similar results were obtained. b, Representative traces of negative-pressure-activated currents recorded from HsTRAAK-transfected cells at a holding potential of −60 mV. Negative pressure was applied from 0 to −210 mm Hg with 10 mm Hg per step. Data from multiple experiments are shown in c. c, The current–pressure relationship of the HsTRAAK channel (n = 5). The currents from each patch were normalized to Imax. The error bar indicates ±s.e.m. P50 is –141.5 ± 4.7 mm Hg. n stands for the number of independent experiments. d, Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography (FSEC) traces of a mouse TPC1 channel with C-terminal GFP and AtOSCA1.1 with C-terminal GFP. The AtOSCA1.1-CGFP protein was eluted as a monodispersed peak at a position (1.86 mL) slightly behind that of the well-characterized mTPC1-CGFP dimer (1.76 mL). An asterisk denotes the position of free GFP. e, Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) traces of AtOSCA1.1. The pooled fractions used for cryo-EM analysis are between the dashes. f, AtOSCA1.1 protein samples of the indicated SEC fractions were subjected to SDS–PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. An asterisk denotes the pooled fractions. g, FSEC traces of wild-type AtOSCA1.1 and two mutants (N124Q and N138Q) with (red) or without (black) PNGase F treatment. PNGase F treatment slightly delayed the peak position of the wild-type protein and the N124Q mutant, while the peak position of N138Q was the same before and after PNGase F treatment. An asterisk denotes the position of free GFP. h, SDS–PAGE of purified AtOSCA1.1 with or without PNGase F treatments. An asterisk denotes the position of the AtOSCA1.1 protein before PNGase F treatment.

Supplementary Figure 2 AtOSCA3.1 is a mechanosensitive channel activated by high pressure.

a, Representative negative-pressure-activated currents recorded from AtOSCA3.1-CGFP-transfected cells at a holding potential of −60 mV in inside-out mode. Negative pressure was applied from −50 to −230 mm Hg with 10 mm Hg per step. b, Currents from seven independent cells were fitted with the Boltzmann equation; the red curve represents data points from a (P50 = –215.9 ± 10.44 mm Hg). c, Representative I–V curves of the AtOSCA3.1channel. Currents were elicited by negative pressure (−220 mm Hg for 150 KGlu–150 KGlu; −230 mm Hg for 150 KGlu–150 KCl; >−230 mm Hg for 150 KGlu–30 KGlu). Data from multiple experiments are shown in d. d, Reversal potentials of the AtOSCA1.1 and AtOSCA3.1 channels in the indicated solutions (n = 3 for 150 KGlu–150 KGlu and 150 KGlu–150 KCl; n = 2 for 150 KGlu–30 KGlu; data are means ± s.e.m.). n stands for the number of independent experiments. e, SEC traces of AtOSCA3.1. The pooled fractions used for cryo-EM analysis are between the dashes. f, AtOSCA3.1 protein samples of the indicated SEC fractions were subjected to SDS–PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. An asterisk denotes the pooled fractions.

Supplementary Figure 3 Cryo-EM image processing procedure of the AtOSCA1.1 channel.

a, Representative raw micrograph of AtOSCA1.1. b, Representative 2D class averages of the cryo-EM particles of AtOSCA1.1. 2D with an apparent twofold rotation symmetry are boxed in red. c, Flowchart of the image processing procedure for AtOSCA1.1. d, Gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curves of the final refined maps for unmasked (blue line) and masked and corrected (purple line). Resolution estimation (4.5 Å for the unmasked map and 3.5 Å for the masked and corrected map) is based on the criterion of an FSC cutoff of 0.143. e, Angular distribution histogram of the final AtOSCA1.1 reconstruction. This is a standard output from cryoSPARC.

Supplementary Figure 4 Single-particle cryo-EM analysis of the AtOSCA1.1 structure.

a,b, Side view (a) and bottom view (b) of local resolution estimation of the final sharpened AtOSCA1.1 cryo-EM density map. c, FSC curves of the model versus half map1 (black line), half map2 (green), and full map (red). d,e, EM density segments (blue mesh) of the 11 transmembrane helices (M0–M10) (d) and representative CTD residues (e) are superimposed on the model in a stick representation.

Supplementary Figure 5 Cryo-EM image processing procedure and single-particle cryo-EM analysis of AtOSCA3.1 structure.

a, Representative 2D class averages of the cryo-EM particles of AtOSCA3.1. b–d, Side (b), top (c), and bottom (d) views of the cryo-EM density map of AtOSCA3.1 fitted to the model. e, Gold-standard FSC curves of the final refined maps for unmasked (black line) and masked and corrected (red line). Resolution estimation (6.2 Å for the unmasked map and 4.8 Å for the masked and corrected map) is based on the criterion of an FSC cutoff of 0.143. f, EM density segments (blue mesh) of the 11 representative transmembrane helices (M0–M10) are superimposed on the model in a stick representation.

Supplementary Figure 6 Sequence alignment of AtOSCA1.1, AtOSCA1.2, AtOSCA3.1, ScCSC1, and HsTMEM63C.

Secondary structure elements are shown above the sequences (α-helices as cylinders, β-sheets as arrows, loops as lines, and unmodeled residues as dashed lines). Conserved and highly conserved residues are highlighted in orange and gray. Cylinders of M0 and M6 are colored in red. Mutations in M0, the pore region, and M6 are boxed in pink, yellow, and brown.

Supplementary Figure 7 20-Å low-pass-filtered cryo-EM density map of AtOSCA1.1 and single-channel currents of AtOSCA1.1.

a,b, Top (a) and bottom (b) views of the cryo-EM density map of AtOSCA1.1 with a 20-Å low-pass filter. Monomer A and B are colored in blue and green. The pore regions (M3, M4, M5, M6, and M7) are colored in magenta and indicated with arrows. c–e, Histograms of negative-pressure-activated wild-type AtOSCA1.1 (c), E462K (d), and E462A (e) single-channel currents at a holding potential of –60 mV with 1-s duration. Bin width is 0.05 pA. f, Reversal potential of wild-type AtOSCA1.1, E462K, and E462A in the indicated solutions (n = 3, data are means ± s.e.m.). n stands for the number of independent experiments.

Supplementary Figure 8 molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the ion permeation pathway.

a,b, Top view (a) and side view (b) of a self-assembled channel-in-lipid bilayer system. The central cavity between the two subunits (in green) was spontaneously filled by lipid molecules (in white), while the pores within both subunits were exposed to the extracellular side. c,d, A continuous water distribution (in orange) formed within one of the subunits during the simulations. Part of the subunit is removed for clarity, and the narrowest part (black circle) is zoomed in d showing the key residues forming the restriction site of the channel.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–8

Supplementary Video 1

Cryo-EM density map and model of AtOSCA1.1. The video first shows the overall density map and fitted atomic model of AtOSCA1.1. The video then shows the 20-Å low-pass filtered map with the putative pore regions (M3, M4, M5, M6, and M7) in magenta.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Wang, D., Kang, Y. et al. Structure of the mechanosensitive OSCA channels. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 850–858 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-018-0117-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-018-0117-6