Abstract

Psychiatric morbidity is high in cities, so identifying potential modifiable urban protective factors is important. We show that exposure to urban green space improves well-being in naturally behaving male and female city dwellers, particularly in districts with higher psychiatric incidence and fewer green resources. Higher green-related affective benefit was related to lower prefrontal activity during negative-emotion processing, which suggests that urban green space exposure may compensate for reduced neural regulatory capacity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

The custom code used for the analyses of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Tost, H., Champagne, F. A. & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1421–1431 (2015).

Peen, J., Schoevers, R. A., Beekman, A. T. & Dekker, J. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 121, 84–93 (2010).

Lederbogen, F. et al. Nature 474, 498–501 (2011).

Haddad, L. et al. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 115–122 (2015).

Triguero-Mas, M. et al. Environ. Res. 159, 629–638 (2017).

Gascon, M. et al. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 4354–4379 (2015).

Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L. M., Knight, T. M. & Pullin, A. S. BMC Public Health 10, 456 (2010).

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., Hahn, K. S., Daily, G. C. & Gross, J. J. Proc. Acad. Natl Sci. USA 112, 8567–8572 (2015).

Park, B. J. et al. J. Physiol. Anthr. 26, 123–128 (2007).

Alcock, I., White, M. P., Wheeler, B. W., Fleming, L. E. & Depledge, M. H. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1247–1255 (2014).

Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Koudela, S., Mutz, G. & Kanning, M. Front. Psychol. 3, 596 (2012).

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. Science 330, 932 (2010).

Hariri, A. R. et al. Science 297, 400–403 (2002).

Pezawas, L. et al. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 828–834 (2005).

Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Nature 468, 194–202 (2010).

Opel, N. et al. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 42, 343–352 (2017).

Phillips, M. L., Drevets, W. C., Rauch, S. L. & Lane, R. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 515–528 (2003).

Stuhrmann, A., Suslow, T. & Dannlowski, U. Biol. Mood Anxiety Disord. 1, 10 (2011).

Häfner, H., Reimann, H., Immich, H. & Martini, H. Soc. Psych. Psych. Epid 4, 126–135 (1969).

Faris, R. E. L. & Dunham, H. W. Mental Disorders in Urban Areas: An Ecological Study of Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses. (University of Chicago Press, 1934).

Lampert, T., Kroll, L. E., Müters, S. & Stolzenberg, H. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 56, 131–143 (2013).

Borkenau, P. & Ostendorf, F. NEO-FFI: NEO-Fünf-Faktoren-Inventar nach Costa und McCrae. (Hogrefe, Göttingen, 2008).

Laux, L., Glanzmann, P., Schaffner, P. & Spielberger, C. D. STAI: Das State-Trait-Angstinventar. (Hogrefe, Göttingen, 1981).

Raine, A. & Benishay, D. J. Pers. Disord. 9, 346–355 (1995).

Krieger, T. et al. J. Affect Disord. 156, 240–244 (2014).

Glaesmer, H., Grande, G., Braehler, E. & Roth, M. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 27, 127–132 (2011).

Traue, H. C., Hrabal, V. & Kosarz, P. Verhalt. und Verhalt. 21, 15–38 (2000).

Goodman, E. et al. Pediatrics 108, e31 (2001).

Margraf, J. Diagnostisches Kurz-Interview bei psychischen Störungen (Mini-DIPS). (Springer, Berlin, 1994).

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M. & van de Schoot, R. Multilevel Analysis. Techniques and Applications. (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, New York, 2017).

Maas, C. J. M. & Hox, J. J. Methodology 1, 86–92 (2005).

Wilhelm, P. & Schoebi, D. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 23, 258–267 (2007).

Collip, D. et al. PLoS ONE 8, e62688 (2013).

Myin-Germeys, I., van Os, J., Schwartz, J. E., Stone, A. A. & Delespaul, P. A. Arch. Gen. Psychiat 58, 1137–1144 (2001).

McIntyre, C. W., Watson, D. & Cunningham, A. C. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 28, 141–143 (1990).

McIntyre, C. W., Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Cross, S. A. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 29, 67–70 (1991).

Vittengl, J. R. & Holt, C. S. Motiv. Emot. 22, 255–275 (1998).

Flory, J. D., Räikkönen, K., Matthews, K. A. & Owens, J. F. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 875–883 (2000).

Törnros, T. et al. Geospat. Health 11, 473 (2016).

Dorn, H. et al. GI_Forum 1, 113–116 (2015).

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N. & Stone, A. A. Science 306, 1776–1780 (2004).

Reichert, M. et al. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 49, 763–773 (2017).

Kanning, M. K., Ebner-Priemer, U. W. & Schlicht, W. M. Front. Psychol. 4, 187 (2013).

Reichert, M. et al. Front. Psychol. 9, 981 (2016).

Koch, E. et al. Front. Psychol. 9, 268 (2018).

Reed, J. & Buck, S. Psychol. Sports Exerc. 10, 581–594 (2009).

Reed, J. & Ones, D. S. Psychol. Sports Exerc. 7, 477–514 (2006).

Haaren, Bvon et al. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 116, 383–394 (2016).

Anastasopoulou, P. et al. PLoS ONE 9, e90606 (2014).

Kanning, M., Ebner-Priemer, U. & Brand, R. J. Sports Exerc. Psychol. 34, 260–269 (2012).

Dunton, G. F., Liao, Y., Intille, S., Huh, J. & Leventhal, A. Health Psychol. 34, 1145–1153 (2015).

Dunton, G. F., Liao, Y., Kawabata, K. & Intille, S. Front. Psychol. 3, 260 (2012).

Liao, Y., Shonkoff, E. T. & Dunton, G. F. Front. Psychol. 6, 1975 (2015).

Keller, M. C. et al. Psychol. Sci. 16, 724–731 (2005).

Kaspar, F. et al. Adv. Sci. Res. 10, 99–106 (2013).

Sprengler, R. The new quality control and monitoring system of the Deutscher Wetterdienst. in Proc. WMO Technical Conference on Meteorological and Environmental Instruments and Methods of Observation https://www.wmo.int/pages/prog/www/IMOP/publications/IOM-75-TECO2002/Papers/2(01)Spengler.doc (2002).

Paek, J., Kim, J. & Govindan, R. Energy-efficient rate-adaptive GPS-based positioning for smartphones. In MobiSys’10. Proc. 8th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services (eds. Banerjee, S., Keshav, S. & Wolman, A.) 299–314 (ACM, 2010).

Kjærgaard, M. B., Bhattacharya, S., Blunck, H. & Nurmi, P. Energy-efficient trajectory tracking for mobile devices. In MobiSys’11. Proc. 9th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services (eds. Agrawala, A., Corner, M. D. & Wetherall, D.) 307–320 (ACM, 2011).

Abdesslem, F., Phillips, A. & Henderson, T. Less is more: energy-efficient mobile sensing with SenseLess. In Proc. 1st ACM workshop on networking, systems, and applications for mobile handhelds 61–62 (ACM, 2009).

Stumpp, J. Platform for interactive ambulatory psychophysiological assessment. Doctoral dissertation, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (2014).

Opitz, D. & Blundell, S. in Object-based Image Analysis. Spatial Concepts for Knowledge-driven Remote Sensing Applications. 1st ed. (eds. Blaschke, T., Lang, S. & Hay, G. J.) 153–167 (Springer, Berlin, 2008).

Blaschke, T. ISPRS J. Photo. Remote Sens. 65, 2–16 (2010).

Opitz, D. W. AAAI/IAAI 379–384 (1999).

Almorox, J., Hontoria, C. & Benito, M. Energ. Convers. Manag. 46, 1465–1471 (2005).

Bolger, N. & Laurenceau, J.-P. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. (The Guilford Press, New York, 2013)

Hox, J. J. Multilevel Analysis. Techniques and Applications. (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, New York, 2010).

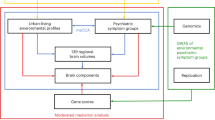

Cao, H. et al. Neuropsychopharmacol. 43, 406–414 (2018).

Cao, H. et al. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 598–605 (2016).

Park, B. J. et al. J. Physiol. Anthr. 26, 123–128 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank H. Häfner, the founder of the Central Institute of Mental Health, for providing a community-oriented reference point19 and inspiration for the current work. We further thank all ‘Monnemer’ participants for kindly supporting our research and C. Akdeniz, C. Stief, B. Höchemer, A. Schäfer, E. Bilek, C. Moessnang, G. Gan and R. Ma for research support. H.T. acknowledges grant support by the German Research Foundation (DFG, Collaborative Research Center SFB 1158 project B04, Collaborative Research Center TRR 265 project A04, GRK 2350 project B2, grant TO 539/3-1) and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant 01EF1803A project WP3, grant 01GQ1102). U.B. acknowledges grant support by the DFG (grant BR 5951/1-1). AML acknowledges grant support by the DFG (Collaborative Research Center SFB 1158 project B09, Collaborative Research Center TRR 265 project S02, grant ME 1591/4-1), BMBF (grants 01EF1803A, 01ZX1314G and 01GQ1003B), European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (grants 602450, 602805, 115300 and HEALTH-F2-2010-241909), Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (IMI, grant 115008) and Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of the State of Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany (MWK, grant 42-04HV.MED(16)/16/1). S.L. acknowledges support by the Klaus Tschira Stiftung. E.S. acknowledges grant support by the DFG (grant SCHW 1768/1-1) and BMBF (grant 01KU1905A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T. designed and coordinated the study, supervised data analyses and wrote the paper. M.R. designed the study, collected and analyzed EMA and sensor data and wrote the paper. U.B. designed the study, collected and analyzed neuroimaging data and wrote the paper. I.R. and E.S. supervised EMA and psychological data analyses and wrote the paper. R.P. and S.L. performed geoinformatic data analyses and wrote the paper. A.H. organized the collection of psychological data, supported psychological data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. U.E.-P. designed the study, supervised EMA and sensor data acquisition and analyses and wrote the paper. A.Z. designed the study, supervised geoinformatic data analyses and wrote the paper. A.M.-L. obtained funding, designed the study and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.M.-L. has received consultant fees from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Atheneum Partners, Blueprint Partnership, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daimler und Benz Stiftung, Elsevier, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, ICARE Schizophrenia, K. G. Jebsen Foundation, L.E.K. Consulting, Lundbeck International Foundation (LINF), R. Adamczak, Roche Pharma, Science Foundation, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Synapsis Foundation – Alzheimer Research Switzerland, System Analytics, and has received lecture fees, including travel fees, from Boehringer Ingelheim, Fama Public Relations, Institut d’investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Janssen-Cilag, Klinikum Christophsbad, Göppingen, Lilly Deutschland, Luzerner Psychiatrie, LVR Klinikum Düsseldorf, LWL PsychiatrieVerbund Westfalen-Lippe, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Reunions i Ciencia S. L., the Spanish Society of Psychiatry, Südwestrundfunk Fernsehen, Stern TV and Vitos Klinikum Kurhessen. All other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Distribution of level-1 residuals.

The histogram depicts the distribution (y-axis shows the frequency) of level-1 (assessment-level) residuals (x-axis), which measure deviations from the conditional mean (conditional residuals) derived from our multilevel model (see Methods, section “Multilevel analysis”) in the combined sample (discovery and replication study; n = 85 participants). Graphical inspection confirmed that there was no obvious deviation from normal distribution providing evidence that our multilevel model is suited to deal with the given data structure.

Supplementary Figure 2 Panel plots depicting the raw-data on subject-level including the estimated random slopes from the multilevel model.

Within-subject associations between green space density and affective valence for each individual: The x-axis shows the individual green space exposure centered on the subjects’ means (range: 0-100%). The y-axis depicts the individuals’ affective valence ratings (range: 0-100). Individual slopes are derived from the random part of the multilevel model (see Methods, section “multilevel analysis”) depicting the individuals’ within-subject effect of green space on affective valence for each of the participants (discovery and replication study; n = 85 participants). The individuals’ raw data points and their random slope estimates are displayed in the same color, respectively. This figure illustrates that although we used a custom-developed sampling strategy (see Methods, section “e-diary sampling strategy”), that is, a mixed time- and location-based sampling strategy which minimizes the shortcomings of traditional time-based strategies and increases the spatial coverage of assessments and data variability within individuals (Ebner-Priemer, U.W., Koudela, S., Mutz, G. & Kanning, M. Interactive Multimodal Ambulatory Monitoring to Investigate the Association between Physical Activity and Affect. Front Psychol 3 (2013); Dorn, H. et al. Incorporating land use in a spatiotemporal trigger for ecological momentary assessments. GI_Forum 2015 – Geospatial Minds for Society 1 113–116 (2015); Törnros, T. et al. A comparison of temporal and location-based sampling strategies for global positioning system-triggered electronic diaries. Geospat Health 11, 473 (2016)), the daily routines and main whereabouts (for example, at home, at work) of participants led to restricted variance in urban green space exposure across the study week. Thus, in a supportive analysis in the combined sample (discovery and replication study; n = 85 participants), we rank ordered the predictor green space exposure within participants and computed an additional multilevel model with exactly the same specifications as in our main model (see Methods, section “multilevel analysis”), but entered the rank ordered green space predictor into the analysis. Here we received only a marginally different effect of urban green space on valence (original green distribution: P = 0.0026; rank ordered green distribution: P = 0.0034; Supplementary Table 8), which further confirmed the robustness of our findings.

Supplementary Figure 3 Causal relation between green space exposure and affect.

Within-subject associations between green space exposure estimates and affective valence for two models with different causal assumptions: (1) green space exposure within the 5 minute time frame prior to the e-diary prompts predicting the following affective valence ratings (that is, model of our main analysis, standardized beta coefficient = 0.056, P = 0.003, left panel) vs. (2) affective valence ratings predicting the green space exposure within the 5 minute time frame following the e-diary prompts (that is, model with inverted causal logic, standardized beta coefficient = 0.017, P = 0.209, right panel). In model (2), all other elements of the model were kept constant with that of our main analysis (see Methods, section “multilevel analysis”). P-values for the beta coefficients are two-sided and derived from the t-statistics of the multilevel model. Dark gray lines illustrate the respective main effect for the estimated green space – affective valence associations. Thus, our data depicted in Fig. 3 above support our hypothesis of a causal effect of urban green space exposure on affective valence in everyday life.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tost, H., Reichert, M., Braun, U. et al. Neural correlates of individual differences in affective benefit of real-life urban green space exposure. Nat Neurosci 22, 1389–1393 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0451-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0451-y

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the nurturing effects of nature on mental health

Nature Mental Health (2024)

-

Das Deutsche Zentrum für Psychische Gesundheit

Der Nervenarzt (2024)

-

Dose-dependent changes in real-life affective well-being in healthy community-based individuals with mild to moderate childhood trauma exposure

Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation (2023)

-

Leveraging neuroscience for climate change research

Nature Climate Change (2023)

-

Environmental neuroscience linking exposome to brain structure and function underlying cognition and behavior

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)