Abstract

The formation of the vertebrate brain requires the generation, migration, differentiation and survival of neurons. Genetic mutations that perturb these critical cellular events can result in malformations of the telencephalon, providing a molecular window into brain development. Here we report the identification of an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mouse mutant characterized by a fractured hippocampal pyramidal cell layer, attributable to defects in neuronal migration. We show that this is caused by a hypomorphic mutation in Vps15 that perturbs endosomal–lysosomal trafficking and autophagy, resulting in an upregulation of Nischarin, which inhibits Pak1 signaling. The complete ablation of Vps15 results in the accumulation of autophagic substrates, the induction of apoptosis and severe cortical atrophy. Finally, we report that mutations in VPS15 are associated with cortical atrophy and epilepsy in humans. These data highlight the importance of the Vps15–Vps34 complex and the Nischarin–Pak1 signaling hub in the development of the telencephalon.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

06 June 2018

In the supplementary information PDF originally posted, there were discrepancies from the integrated supplementary information that appeared in the HTML; the former has been corrected as follows. In the legend to Supplementary Fig. 2c, “major organs of the mouse” has been changed to “major organs of the adult mouse.” In the legend to Supplementary Fig. 6d,h, “At E14.5 Mbe/Mbe mutants have a smaller percentage of Brdu positive cells in bin 3” has been changed to “At E14.5 Mbe/Mbe mutants have a higher percentage of Brdu positive cells in bin 3.”

References

Ayala, R., Shu, T. & Tsai, L. H. Trekking across the brain: the journey of neuronal migration. Cell 128, 29–43 (2007).

Noctor, S. C., Flint, A. C., Weissman, T. A., Dammerman, R. S. & Kriegstein, A. R. Neurons derived from radial glial cells establish radial units in neocortex. Nature 409, 714–720 (2001).

Heng, J. I., Chariot, A. & Nguyen, L. Molecular layers underlying cytoskeletal remodelling during cortical development. Trends Neurosci. 33, 38–47 (2010).

Gleeson, J. G. & Walsh, C. A. Neuronal migration disorders: from genetic diseases to developmental mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 23, 352–359 (2000).

D’Arcangelo, G. et al. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature 374, 719–723 (1995).

Sheldon, M. et al. Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice. Nature 389, 730–733 (1997).

Keays, D. A. et al. Mutations in alpha-tubulin cause abnormal neuronal migration in mice and lissencephaly in humans. Cell 128, 45–57 (2007).

Chae, T. et al. Mice lacking p35, a neuronal specific activator of Cdk5, display cortical lamination defects, seizures, and adult lethality. Neuron 18, 29–42 (1997).

Dhavan, R. & Tsai, L. H. A decade of CDK5. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 749–759 (2001).

Keays, D. A., Clark, T. G. & Flint, J. Estimating the number of coding mutations in genotypic- and phenotypic-driven N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) screens. Mamm. Genome 17, 230–238 (2006).

Corbo, J. C. et al. Doublecortin is required in mice for lamination of the hippocampus but not the neocortex. J. Neurosci. 22, 7548–7557 (2002).

Hirotsune, S. et al. Graded reduction of Pafah1b1 (Lis1) activity results in neuronal migration defects and early embryonic lethality. Nat. Genet. 19, 333–339 (1998).

Stack, J. H., Herman, P. K., Schu, P. V. & Emr, S. D. A membrane-associated complex containing the Vps15 protein kinase and the Vps34 PI 3-kinase is essential for protein sorting to the yeast lysosome-like vacuole. EMBO J. 12, 2195–2204 (1993).

Stein, M. P., Feng, Y., Cooper, K. L., Welford, A. M. & Wandinger-Ness, A. Human VPS34 and p150 are Rab7 interacting partners. Traffic 4, 754–771 (2003).

Sun, Q., Westphal, W., Wong, K. N., Tan, I. & Zhong, Q. Rubicon controls endosome maturation as a Rab7 effector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19338–19343 (2010).

Ruas, M. et al. TPC1 has two variant isoforms, and their removal has different effects on endo-lysosomal functions compared to loss of TPC2. Mol. Cell Biol. 34, 3981–3992 (2014).

Tanida, I., Ueno, T. & Kominami, E. LC3 and autophagy. Methods Mol. Biol. 445, 77–88 (2008).

Hara, T. et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 441, 885–889 (2006).

Schwämmle, V., León, I. R. & Jensen, O. N. Assessment and improvement of statistical tools for comparative proteomics analysis of sparse data sets with few experimental replicates. J. Proteome Res. 12, 3874–3883 (2013).

Lim, K. P. & Hong, W. Human Nischarin/imidazoline receptor antisera-selected protein is targeted to the endosomes by a combined action of a PX domain and a coiled-coil region. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54770–54782 (2004).

Alahari, S. K., Reddig, P. J. & Juliano, R. L. The integrin-binding protein Nischarin regulates cell migration by inhibiting PAK. EMBO J. 23, 2777–2788 (2004).

Seress, L., Gulyás, A. I. & Freund, T. F. Pyramidal neurons are immunoreactive for calbindin D28k in the CA1 subfield of the human hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 138, 257–260 (1992).

Nemazanyy, I. et al. Defects of Vps15 in skeletal muscles lead to autophagic vacuolar myopathy and lysosomal disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 5, 870–890 (2013).

Gorski, J. A. et al. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1-expressing lineage. J. Neurosci. 22, 6309–6314 (2002).

Goebbels, S. et al. Genetic targeting of principal neurons in neocortex and hippocampus of NEX-Cre mice. Genesis 44, 611–621 (2006).

Akizu, N. et al. Biallelic mutations in SNX14 cause a syndromic form of cerebellar atrophy and lysosome-autophagosome dysfunction. Nat. Genet. 47, 528–534 (2015).

Sobreira, N., Schiettecatte, F., Valle, D. & Hamosh, A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum. Mutat. 36, 928–930 (2015).

Rostislavleva, K. et al. Structure and flexibility of the endosomal Vps34 complex reveals the basis of its function on membranes. Science 350, aac7365 (2015).

Vadlamudi, R. K. et al. p21-activated kinase 1 regulates microtubule dynamics by phosphorylating tubulin cofactor B. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 3726–3736 (2005).

Arber, S. et al. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature 393, 805–809 (1998).

Ding, Y., Milosavljevic, T. & Alahari, S. K. Nischarin inhibits LIM kinase to regulate cofilin phosphorylation and cell invasion. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 3742–3756 (2008).

Chai, X., Förster, E., Zhao, S., Bock, H. H. & Frotscher, M. Reelin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of neuronal processes by inducing n-cofilin phosphorylation at serine3. J. Neurosci. 29, 288–299 (2009).

Schmid, R. S. et al. alpha3beta1 integrin modulates neuronal migration and placement during early stages of cerebral cortical development. Development 131, 6023–6031 (2004).

Waugh, M. G. PIPs in neurological diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1851, 1066–1082 (2015).

Rivière, J. B. et al. De novo germline and postzygotic mutations in AKT3, PIK3R2 and PIK3CA cause a spectrum of related megalencephaly syndromes. Nat. Genet. 44, 934–940 (2012).

Mirzaa, G. M. et al. Characterisation of mutations of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit, PIK3R2, in perisylvian polymicrogyria: a next-generation sequencing study. Lancet Neurol. 14, 1182–1195 (2015).

Stopkova, P. et al. Identification of PIK3C3 promoter variant associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 55, 981–988 (2004).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Bejarano, E. et al. Connexins modulate autophagosome biogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 401–414 (2014).

Dull, T. et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J. Virol. 72, 8463–8471 (1998).

Sun, T. et al. Acetylation of Beclin 1 inhibits autophagosome maturation and promotes tumour growth. Nat. Commun. 6, 7215 (2015).

Feng, W. et al. Dissection of autophagy in human platelets. Autophagy 10, 642–651 (2014).

Ma, Y. et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 differentially regulate doxorubicin induced cardiomyopathy in mice. PLoS ONE 7, e40763 (2012).

Lee, H. et al. Pathological roles of the VEGF/SphK pathway in Niemann-Pick type C neurons. Nat. Commun. 5, 5514 (2014).

Willy, J. A. et al. Function of inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase isoform α (IBTKα) in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis links autophagy and the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 14050–14065 (2017).

Jana, N. R., Tanaka, M., Wang, Gh & Nukina, N. Polyglutamine length-dependent interaction of Hsp40 and Hsp70 family chaperones with truncated N-terminal huntingtin: their role in suppression of aggregation and cellular toxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2009–2018 (2000).

Santoh, M. et al. Acetaminophen induces accumulation of functional rat CYP3A via polyubiquitination dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 6, 21373 (2016).

Rinaldi, C. et al. Insulinlike growth factor (IGF)-1 administration ameliorates disease manifestations in a mouse model of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Mol. Med. 18, 1261–1268 (2012).

Walls, K. C. et al. Lysosome dysfunction triggers Atg7-dependent neural apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10497–10507 (2010).

Bertrand, T. et al. Conformations of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) orchestrate neuronal survival by a crosstalk between EGFR and NMDAR. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1924 (2015).

Li, S., Leshchyns’ka, I., Chernyshova, Y., Schachner, M. & Sytnyk, V. The neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) associates with and signals through p21-activated kinase 1 (Pak1). J. Neurosci. 33, 790–803 (2013).

Breuss, M. et al. Mutations in the β-tubulin gene TUBB5 cause microcephaly with structural brain abnormalities. Cell Rep. 2, 1554–1562 (2012).

Vandesompele, J. et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3, H0034 (2002).

Boda, E., Pini, A., Hoxha, E., Parolisi, R. & Tempia, F. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies in mouse brain. J. Mol. Neurosci. 37, 238–253 (2009).

Pichler, P. et al. Peptide labeling with isobaric tags yields higher identification rates using iTRAQ 4-plex compared to TMT 6-plex and iTRAQ 8-plex on LTQ Orbitrap. Anal. Chem. 82, 6549–6558 (2010).

Kita, Y., Kawakami, K., Takahashi, Y. & Murakami, F. Development of cerebellar neurons and glias revealed by in utero electroporation: Golgi-like labeling of cerebellar neurons and glias. PLoS ONE 8, e70091 (2013).

Chu, Y. Y. et al. Astrocytic CCAAT/enhancer binding protein delta regulates neuronal viability and spatial learning ability via miR-135a. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 4173–4188 (2016).

Navarro-Quiroga, I., Hernandez-Valdes, M., Lin, S. L. & Naegele, J. R. Postnatal cellular contributions of the hippocampus subventricular zone to the dentate gyrus, corpus callosum, fimbria, and cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 497, 833–845 (2006).

Vasistha, N. A. et al. Cortical and clonal contribution of Tbr2 expressing progenitors in the developing mouse brain. Cereb. Cortex 25, 3290–3302 (2015).

Boekhoorn, K. et al. Doublecortin (DCX) and doublecortin-like (DCL) are differentially expressed in the early but not late stages of murine neocortical development. J. Comp. Neurol. 507, 1639–1652 (2008).

Hendzel, M. J. et al. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma 106, 348–360 (1997).

Shah, B. et al. C3G/Rapgef1 is required in multipolar neurons for the transition to a bipolar morphology during cortical development. PLoS ONE 11, e0154174 (2016).

Mullen, R. J., Buck, C. R. & Smith, A. M. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development 116, 201–211 (1992).

Nóbrega, C. et al. Silencing mutant ataxin-3 rescues motor deficits and neuropathology in Machado-Joseph disease transgenic mice. PLoS ONE 8, e52396 (2013).

Keays, D. A. et al. The role of Tuba1a in adult hippocampal neurogenesis and the formation of the dentate gyrus. Dev. Neurosci. 32, 268–277 (2010).

Castellano, B. et al. A double staining technique for simultaneous demonstration of astrocytes and microglia in brain sections and astroglial cell cultures. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 39, 561–568 (1991).

Gonchar, Y., Wang, Q. & Burkhalter, A. Multiple distinct subtypes of GABAergic neurons in mouse visual cortex identified by triple immunostaining. Front. Neuroanat. 1, 3 (2008).

Gandal, M. J. et al. GABAB-mediated rescue of altered excitatory-inhibitory balance, gamma synchrony and behavioral deficits following constitutive NMDAR-hypofunction. Transl. Psychiatry 2, e142 (2012).

Pillai, A. G. et al. Dendritic morphology of hippocampal and amygdalar neurons in adolescent mice is resilient to genetic differences in stress reactivity. PLoS ONE 7, e38971 (2012).

Bas-Orth, C., Tan, Y. W., Oliveira, A. M., Bengtson, C. P. & Bading, H. The calmodulin-binding transcription activator CAMTA1 is required for long-term memory formation in mice. Learn. Mem. 23, 313–321 (2016).

Oliver, P. L., Keays, D. A. & Davies, K. E. Behavioural characterisation of the robotic mouse mutant. Behav. Brain Res. 181, 239–247 (2007).

Deacon, R. M. & Rawlins, J. N. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nat. Protoc. 1, 7–12 (2006).

Marco-Sola, S., Sammeth, M., Guigó, R. & Ribeca, P. The GEM mapper: fast, accurate and versatile alignment by filtration. Nat. Methods 9, 1185–1188 (2012).

Derrien, T. et al. Fast computation and applications of genome mappability. PLoS ONE 7, e30377 (2012).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80–92 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the family for the donation of the genetic and biological material. We also acknowledge the input of P. Potter and S. Wells from the mutagenesis program at MRC Harwell and the MRC funding that underpinned it (MC U142684172). We are indebted to R. Williams for modeling the VPS15 human mutation. We also thank the transgenic, bio-optics, proteomic and graphics services groups at the IMP/IMBA. We thank The National Center for Medical Genomics (LM2015091) for providing allelic frequencies in ethnically matched populations (project CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_013/0001634). We thank Boehringer Ingelheim and the FWF for funding this research (D.A.K., I914, P24267). The human studies were funded by the European Community’s 7th Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013). S.K., A.P. and V.S. were supported by institutional programs of Charles University in Prague (UNCE 204011, PROGRES-Q26/LF1 and SVV 260367/2017). We acknowledge grants 15-28208A and RVO-VFN 64165 from the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic and the project LQ1604 NPU II from the Ministry of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E., J.F. and D.A.K. performed the phenotypic screen and genetic mapping. T.M.K. and D.J.A. did the whole-exome sequencing on the Marble mouse. T.G., G.R. and T.Hochstoeger analyzed the expression of Vps15. T.G., I.L., M.B., S.P.-C., A.H.H., R.T. and L.L. were responsible for the characterization of the Marble and KO mouse lines. K.M. and G.D. undertook the mass spectroscopy experiments. M.R. and T.G. performed the in utero electroporation analysis. A.P., T.Honzik, M.G., S.B., E.S., S.K., V.S. and I.G. collated the clinical data and performed whole-exome sequencing and analysis of the L1224R patient. T.G. performed the functional experiments. A.K.T., T.G. and J.Z. designed and performed the lentiviral rescue experiment. T.G. and D.A.K. wrote the manuscript and all authors commented on it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations

Integrated Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figure 1 Genetic mapping of the Marble mutation

a Schematic showing the parameters assessed for the ENU screen. Nissl stained stereotaxically matched sections through the telencephalon (Bregma −2.06 mm) were analyzed. The following measurements were taken: thickness of the cortex; volume of the corpus callosum; thickness of the stratum oriens of the hippocampus; length of the pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus; thickness of the radial and molecular layer of the hippocampus; length of the dentate gyrus; and volume of the third ventricle and lateral ventricles. b Schematic showing the results for the genetic mapping experiments. The marker and its position along chromosome 9 are shown on the left, and the number of animals with that particular genotype are shown at the bottom. Filled black boxes indicate homozygosity for the ENU mutagenized C57/BL6 allele, whereas clear boxes indicate the presence of at least one C3H/HeH allele. The causative mutation was mapped to a 28.6 Mb interval between D9mit11 and D9mit81. c Sequencing traces of Vps15 cDNA for +/+, +/Mbe, Mbe/Mbe. mRNA was extracted from the developing forebrain of animals at E14.5, and cDNA generated by reverse transcription. In Mbe/Mbe animals the insertion of a stop codon (TAG) can be seen. d-m Representative Nissl stains of brains of adult +/+ and +/+/BAC mice (n = 3 animals per genotype). No structural brain abnormalities were observed in +/+/BAC transgenic mice harboring additional copies of Vps15 i-m in comparison to littermate wild-type controls d-h. Boxed areas in d and i highlight the cortex (magnified in e and j) and the CA1 region of the hippocampus (magnified in f and k). g and l show the cerebellum. Boxed areas are magnified in h and m. The scale bars in i show 1000 μm, 200 μm in j, 100 μm in k and m and 500 μm in l.

Supplementary Figure 2 Expression of Vps15 and functional analysis of the Marble mutation

a-c qPCR results showing the expression of Vps15 in: a the developing mouse brain from E10.5 to P6; b in the adult mouse brain; and c in the major organs of the adult mouse. Vps15 was expressed in all tissues analyzed (n = 2-3 technical replicates on a pooled sample of 3 biological samples). d Western blot analysis of Vps15, Vps34 and Beclin1 levels in MEFs taken from +/+ and Mbe/Mbe animals. Cropped images are shown. Gapdh was employed as a loading control. e Relative quantitation of the protein levels shown in d reveals a significant reduction in Vps15 (n = 3 animal per genotype; one-tailed unpaired t-test, t4 = 9.467; P = 0.0003), Vps34 (n = 3 animals per genotype; one-tailed unpaired t-test, t4 = 8.44; P = 0.0005), and Beclin1 in Mbe/Mbe mutants (n = 3 animals per genotype; one-tailed unpaired t-test, t4 = 7.877; P = 0.0007). f qPCR results for transcript levels of Vps15, Vps34 and Beclin1 from E14.5 brains. While the transcript levels of Vps15 are lower, there are no significant differences between genotypes (n = 3 animals per genotype; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison; +/+ vs Mbe/Mbe: Vps15: P = 0.1911; Vps34: P = 0.7545; Beclin1: P = 0.6128) g-h Western blot analysis of Vps15 employing a N-terminal antibody in MEFs and Neuro2A (N2A) cells. Cropped images are shown. N2A cells were transfected with a shortened version of Vps15 (1-289) reflecting the predicted length of the Mbe/Mbe truncated protein. g The N-terminal Vps15 antibody detected full-length Vps15 at physiological levels in +/+ MEFs and N2A cells (highlighted with black arrow head). A C-terminal Vps15 antibody confirmed that the band is Vps15. h The N-terminal Vps15 antibody binds Vps15(1-289) with high affinity but does not detect a band at the corresponding size in either +/+ or Mbe/Mbe MEFs. These data indicate that the Marble mutation does not lead to the expression of a truncated protein, most likely due to nonsense mediated decay of the transcript. i Levels of PDGFR receptor β after stimulation with receptor ligand PDGF-BB in +/+ (blue line) and Mbe/Mbe (red line) MEFs (n = 3). j PDGF receptor half-life was calculated from fitted data in i. Mbe/Mbe cells show significantly slower receptor degradation (n = 3 animals per genotype, one-tailed unpaired t-test, t4 = 2.633; P = 0.029). k Representative FACs plot of MEFs stained with lysotracker for +/+ and Mbe/Mbe animals. The Y axis shows the cell count and the intensity of staining is shown on the X axis. l Quantitation of lysotracker results reveals no significant difference between +/+ and Mbe/Mbe animals (n = 3 animals per genotype; unpaired t-test, t4 = 1.022; P = 0.3645). Error bars show mean +/- standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Figure 3 Expression analysis of Nischarin

a-b qPCR results showing the expression of Nischarin in a the developing mouse brain from E12.5 to P6 and b in the major organs of the adult mouse (n = 3 animals per genotype). Nischarin was expressed in all tissues analyzed, with highest expression levels in the developing brain (E12.5 to E16.5). c-f Representative images of P11 mouse brains stained with sera against Nischarin. Boxed areas in c and d are magnified in e and f. Pyramidal neurons located in the oriens layer (OL) were notable for the strong Nischarin staining (black arrow heads). g Quantification revealed significantly higher Nischarin staining for cells found in the oriens layer (OL) as compared to those located in the pyramidal cell layer (PL) (n = 3 animals per genotype; one-tailed unpaired t-test; t4 = 2.212; P = 0.0457). The scale bar shows 500 μm in c and 100 μm in e. Error bars show mean +/- standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Figure 4 Analysis of hippocampal neurons in Mbe/Mbe mutants

(a-m) Representative images of brains from 8-week old mice stained with sera against calretinin (a-f) and parvalbumin (h-m). Quantification showing the percentage of calretinin positive (g) or parvalbumin positive (n) interneurons in the oriens layer (OL). There was no significant difference when comparing Mbe/Mbe animals and littermate controls (+/+, +/Mbe) (n = 3 animals per genotype; calretinin: one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; +/+ vs Mbe/Mbe; P = 0.8137; parvalbumin: Kruskal-Wallis test with a Dunn’s multiple comparison test; +/+ vs Mbe/Mbe; P>0.9999). (o) Image of a Golgi stained pyramidal neuron from the hippocampus. Spines located on tertiary apical dendritic branches distanced more than 120μm from the soma (red line) were quantitated. (p) Quantification of spine density in +/+ and Mbe/Mbe animals reveals no significant differences between genotypes (n = 4-6 neurons per animal; n = 3 animals per genotype; two-tailed unpaired t-test; t4 = 0.3386; P = 0.7519). (q) Schematic representation of CA1 pyramidal neurons that were traced in three dimensions and assessed by Scholl analysis. (r) Quantitation of dendritic intersections from the soma. Ectopic Mbe/Mbe neurons exhibit a significant decrease in complexity, that is most evident 100 μm to 160 μm from the soma (n = 3 cells per animal, n = 3 animals per genotype; two-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; interaction P<0.0001, Supplementary Table 1). The scale bars in (c), and (j) show 500 μm, 100 μm in (f) and (m) and 50 μm in (o). Error bars show mean +/- standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Figure 5 The Marble mouse does not show obvious defects in the dentate gyrus nor deficits in locomotion or anxiety

a-x Representative images of histological stainings on the dentate gyrus of adult +/+, +Mbe, and Mbe/Mbe animals with sera against Prox1 (which labels mature granule cells), GFAP (which labels radial glial-like progenitors), Dcx (which labels newly born neurons), and Tbr2 (which labels intermediate progenitors). These experiments revealed that the granule cell layer and the subgranular zone is similarly organized in all genotypes (n = 3 animals per genotype). y Total distance travelled in the open field reveals no locomotor phenotype in Mbe/Mbe animals (n = 17 animals per genotype; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, Bonferroni corrected; +/+ vs Mbe/Mbe; P>0.9999). z Number of entries into the center of the open field. There is no significant difference between genotypes indicating anxiety phenotypes are normal in Mbe/Mbe animals (n = 17 animals per genotype; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, Bonferroni corrected; +/+ vs Mbe/Mbe; P = 0.7546). The scale bars show 500 μm in a and 100 μm b. Error bars show mean +/- standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Figure 6 Anatomical characterization of the Marble cortex and cerebellum

a-g Representative images of birth date labeling studies following the injection of BrdU in pregnant dams at E12.5 a-c and E14.5 e-g followed by histological analysis at P0. Cortical sections were divided into ten equal bins, cells counted blind to genotype, and then the relative number of BrdU positive cells calculated for each bin. Bin 10 represents the deepest bin, with bin 1 being closest to the cortical surface. d, h Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference when comparing +/Mbe heterozygotes with Mbe/Mbe mutants at E12.5 in bin 7 (n = 5 animals per genotype; two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple correction test; +/Mbe vs Mbe/Mbe P = 0.0242) and at E14.5 in bin 3 (n = 3 animals per genotype; two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple correction test; +/Mbe vs Mbe/Mbe P = 0.0465). At E14.5 Mbe/Mbe mutants have a higher percentage of Brdu positive cells in bin 3 indicative of a mild defect in neuronal migration. Unexpectedly, at E12.5 fewer cells are in bin 7, suggesting mildly faster migration. i-q Analysis of the cerebellum in +/+, +/Mbe, and Mbe/Mbe animals. Panels i-k show representative images of Nissl staining, l-n Foxp2 staining, and o-q Calbindin staining. The molecular layer, Purkinje cell layer, and granule cell layer all appear intact in Mbe/Mbe mutants (n = 3 animals per genotype). Error bars show mean +/- standard error of the mean. The scale bars in c and g show 200 μm and 150 μm in q.

Supplementary Figure 7 Control experiments for in utero electroporation studies

a Western blot analysis of Nischarin in Neuro2A cells transfected with a shmiRNAs targeting Nischarin (shmiNISCH) or a scrambled negative control (shmiNEG). Cropped images are shown. b Quantification revealed a 60% reduction in Nischarin protein levels following transfection with a shmiNISCH (n = 3 flasks, one-tailed Mann Whitney test; P = 0.05). c-h Representative images for in utero electroporation experiments. Constructs were electroporated at E14.5 before analysis at E17.5. GFP positive cells were quantified in 3 blinded sections per animal in 9 areas across the developing cortex and expressed relative to the total number of cells. e, h Electroporation of a knock-down construct targeting Nischarin c-e or of a phosphomimetic mutant of Pak1(T422E) f-h in wild-type animals did not significantly influence neuronal migration (two-way repeated measures ANOVA with a Bonferroni multiple comparison test; shmiNISCH: n = 4 animals per condition, interaction P = 0.7074; Pak1(T422E): n = 5 animals per condition, interaction P = 0.3652). i-n Representative images of mouse brains electroporated with either Nischarin or pCAGEN control vector followed by immunostaining with sera targeting Nischarin (n = 3 animals per genotype). i-k Cells with highest levels of Nischarin congregated in the subventricular and intermediate zones. l-n No immunoreactivity for Nischarin was found in mouse brains electroporated with the control vector when employing those imaging conditions used in i-k. Note that these imaging conditions do not allow detection of the endogenous protein. Error bars show mean +/- standard error of the mean. The scale bar shows 100 μm in c, f, i and l.

Supplementary Figure 8 Neuroanatomical characterization of Vps15 fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals at E14.5.

a-c Representative coronal Nissl stains of the developing E14.5 cortex of +/fl, +/fl Emx1-Cre, and fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals. d Quantitation of cortical thickness. fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals have a thinner cortex, but this is not significantly different from +/fl animals (n = 3 animals per genotype; Kruskal-Wallis test with a Dunn’s correction for multiple testing, Bonferroni corrected; +/fl vs fl/fl Emx1-Cre; P = 0.0714). Analogous to our P0 and P11 results (Figure 6) we did not observe a phenotype in +/fl Emx1-Cre heterozygotes. These animals were employed as controls for subsequent stainings. e-f Caspase staining of the cortex at E14.5 of +/fl Emx1-Cre and fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals. Caspase positive cells can be observed in both proliferative and postmitotic regions in fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals. g Quantification of the number of caspase positive cells reveals a significant difference between genotypes (n = 3 animals per genotype; unpaired t-test; one-tailed with a Bonferroni correction; t4 = 8.779; P = 0.0035). h-i Staining with the progenitor marker Sox2 at E14.5 of +/fl EMX1-Cre and fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals. j Quantitation of the thickness of the Sox2 positive layer shows that it is thinner in fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals, but this difference is not statistically significant (n = 3 animals per genotype; unpaired t-test; one-tailed with a Bonferroni correction; t4 = 3.455; P = 0.091). k-l Staining with the intermediate progenitor marker Tbr2 at E14.5. m Quantitation of the thickness of the Tbr2 positive layer, shows that it is thinner in fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals, but this difference is not statistically significant (n = 3 animals per genotype; unpaired t-test; one-tailed with a Bonferroni correction; t4 = 2.867; P = 0.1596). n-o Staining with the early neuronal marker DCX at E14.5. p Quantitation of the thickness of the DCX positive layer shows that it is thinner in fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals but this difference is not statistically significant (n = 3 animals per genotype; unpaired t-test; one-tailed with a Bonferroni correction; t4 = 3.217; P = 0.1134). q-r Staining with the M-phase marker pH3 at E14.5. (s) Quantitation of the number of ventricular and abventricular pH3 positive cells reveals a reduction fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals, but this difference is not statistically significant (n = 3 animals per genotype; two-tailed unpaired t-test; with a Bonferroni correction; abventricular: t4 = 2.299; P = 0.581; ventricular; t4 = 0.4494; P>0.9999). (t-u) Staining with the radial glial marker Nestin at E14.5. Distinct radial glial fibers can be observed in control animals (+/fl Emx1-Cre), in contrast to fl/fl Emx1-Cre animals where fibers form thick bundles in the developing cortical plate (shown with an arrow). Images in (a-u) are representative. Scale bars in c and f show 50 μm. Error bars show mean +/- standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Figure 9 Analysis of human dermal fibroblasts obtained from a patient with a L1224R mutation in VPS15

a Sequencing traces of the A to C variant in VPS15 that encodes for a L1224R missense mutation in the homozygous proband. b Homology comparison of the L1224 residue in mice, xenopus, zebrafish, and drosophila reveals it is highly conserved. c Quantitation of relative mRNA expression of VPS15, VPS34 and BECLIN1 in dermal fibroblasts from the father, mother and proband. No significant differences were observed on the levels of VPS15 transcript (n = 3 flasks per individual; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison; father vs proband: P = 0.8928; mother vs proband: P = 0.9998), on the levels of VPS34 transcript (n = 3 flasks per individual; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison; father vs proband: P = 0.9429; mother vs proband: P = 0.2655) or on the levels of BECLIN1 transcript (n = 3 individual flasks; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison; father vs proband: P = 0.8377; mother vs proband: P = 0.1506). See Supplementary Table 1. These data indicate the that the reduction in VPS15 protein levels is due to post-transcriptional dysregulation. d Western blot analysis of LC3-I, and LC3-II on protein lysates prepared from patient and parent HDFs before and after lysosomal inhibition with Bafilomycin A1 (n = 3 flasks per individual). Cropped images are shown. Quantification e-g reveals a reduction in the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I at 0hrs, but this is not statistically significant (one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison, Bonferroni corrected; father vs proband: P>0.9999, mother vs proband: P>0.9999). Similarly when assessing autophagy flux (2hr-0hr) and formation at (4hr-2h) we observe a reduction in L1224R fibroblasts, however, this is not significant (one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison, Bonferroni corrected; 2hr-0hr: father vs proband: P>0.9999, mother vs proband: P>0.9999; 4hr-2hr: father vs proband: P = 0.1836, mother vs proband: P = 0.1482). h Representative FACs plot for lysotracker experiments conducted on HDFs from the mother (shown in dark blue), father (shown in light blue), and proband (shown in red). The Y axis shows the cell count and the intensity of staining is shown on the X axis. i Quantification of the median intensity of lysotracker staining shows a mild but significant reduction in the proband in comparison to the father (n = 3 flasks per individual, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison, father vs. proband P = 0.0466). Error bars indicate mean +/- standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Figure 10 Model showing the effect of Vps15 mutations on neuronal migration and cell survival

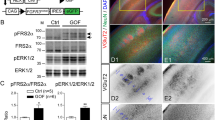

Under wild-type conditions Vps15 acts in a complex with Vps34 and Beclin1 catalyzing the formation of the phospholipid PI(3)P at endosomes and autophagosomes. The splice site mutation in the Marble mouse is a hypomorph, reducing the levels of the Vps15/Vps34 complex which impairs endosome (E) to lysosome (L) trafficking. As a consequence, Nischarin, a protein that binds PI(3)P and is localized to the endosome, is upregulated in Marble mutants. Nischarin inhibits Pak1 phosphorylation, which is known to influence microtubule dynamics through the phosphorylation of tubulin cofactor B and the actin cytoskeleton by activating LIM kinase. We propose that perturbation of this pathway causes the neuronal migration defect in Marble animals. If Vps15 is deleted in neurons, autophagy progression is blocked leading to the accumulation of p62 positive substrates. This in turn is associated with caspase induced cell death and severe cortical atrophy.

Supplementary Figure 11 Full scans of all western blots presented in this manuscript

In some instances western blot membranes were cut allowing incubation with different antibodies. Shown are the full scans of each membrane fragment.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–11.

Supplementary Table 1

Statistical analysis of data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gstrein, T., Edwards, A., Přistoupilová, A. et al. Mutations in Vps15 perturb neuronal migration in mice and are associated with neurodevelopmental disease in humans. Nat Neurosci 21, 207–217 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-017-0053-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-017-0053-5

This article is cited by

-

Macroautophagy in CNS health and disease

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2022)

-

Autophagy deficiency in neurodevelopmental disorders

Cell & Bioscience (2021)

-

Cul3 regulates cytoskeleton protein homeostasis and cell migration during a critical window of brain development

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Mendelian neurodegenerative disease genes involved in autophagy

Cell Discovery (2020)

-

Coupling of terminal differentiation deficit with neurodegenerative pathology in Vps35-deficient pyramidal neurons

Cell Death & Differentiation (2020)