Abstract

Patients with cancer have high mortality from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and the immune parameters that dictate clinical outcomes remain unknown. In a cohort of 100 patients with cancer who were hospitalized for COVID-19, patients with hematologic cancer had higher mortality relative to patients with solid cancer. In two additional cohorts, flow cytometric and serologic analyses demonstrated that patients with solid cancer and patients without cancer had a similar immune phenotype during acute COVID-19, whereas patients with hematologic cancer had impairment of B cells and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-specific antibody responses. Despite the impaired humoral immunity and high mortality in patients with hematologic cancer who also have COVID-19, those with a greater number of CD8 T cells had improved survival, including those treated with anti-CD20 therapy. Furthermore, 77% of patients with hematologic cancer had detectable SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses. Thus, CD8 T cells might influence recovery from COVID-19 when humoral immunity is deficient. These observations suggest that CD8 T cell responses to vaccination might provide protection in patients with hematologic cancer even in the setting of limited humoral responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

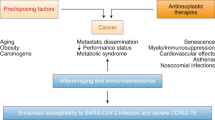

Severe infection with COVID-19 has been linked to immune dysregulation, including impaired or delayed production of type I and type III interferons1,2,3,4,5, marked lymphopenia6,7,8,9,10 and a paradoxical increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-61,4,6,11,12,13. Alteration of T cell compartments include increases in effector and activated CD4 and CD8 T cells14,15,16,17, whereas changes in B cell and humoral compartments include robust plasmablast differentiation and production of SARS-CoV-2-reactive IgM and IgG antibodies14,18,19,20. More recently, distinct immunophenotypes have been associated with COVID-19 disease severity and trajectory3,4,11,14,15. Understanding how clinical features affect the host immune response to SARS-CoV-2 will elucidate determinants of disease severity.

Patients with cancer have an increased risk of severe COVID-19 (refs. 21,22,23,24), with an estimated case fatality rate of 25%25 compared to 2.7% in the general population26. Importantly, cancer is a heterogeneous disease with mortality rates as high as 55% among patients with COVID-19 who also have hematologic cancer21,24,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. It is less apparent whether the increased mortality by cancer subtype is independent of the confounding effects of other prognostic factors, including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status35, which is the most important predictor of death in the population of patients with cancer36. Furthermore, there are limited data on the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with cancer, whether it differs by cancer subtype, whether it is affected by immune-modulating therapies such as B cell-depleting therapy and, most importantly, how each of these factors influence mortality in the setting of COVID-19. We studied three cohorts of patients with cancer who also have acute COVID-19 across two hospital systems to understand the immunologic determinants of COVID-19 mortality in cancer.

Results

Hematologic cancer is a risk factor for COVID-19 mortality

We first conducted a prospective multi-center observational cohort study of patients with cancer who were hospitalized with COVID-19 (COVID-19 Outcomes in Patients with Cancer (COPE); Methods). The median age of this cohort was 68 years; 48% were female, 54% were Black and 57% were current or former smokers (Table 1). In terms of cancer-specific factors, 78% of patients had solid cancer, with prostate and breast cancer most prevalent; 46% had active cancer, defined as diagnosis or treatment within 6 months; and 49% had a recorded ECOG performance status of 2 or higher (Table 1). During follow-up, 48% of patients required intensive care unit (ICU) level care, and 38% of patients died within 30 d of admission (Supplementary Table 1). Demographics by tumor type are available in Supplementary Table 2.

We performed univariate analyses to identify factors associated with all-cause mortality in the period between hospital admission and 30 d after discharge. We included relevant covariates, including patient factors such as age, race, gender and smoking history (ever versus never)37,38,39,40; cancer-specific factors including ECOG performance status33,35 and status of cancer (for example, active versus remission)34; cancer type (for example, hematologic versus solid cancer)27,32,34,41,42; and cancer treatment33,35. Current or previous smoking (P = 0.028), poor ECOG performance status (ECOG 3–4, P = 0.001) and active cancer status (P = 0.024) (Fig. 1) were all associated with increased COVID-19 mortality. Consistent with recent data, patients with hematologic cancer appeared to have an increased risk of mortality relative to patients with solid cancer (55% versus 33% respectively; P = 0.075) (Supplementary Table 1)21,27,32,33,34,41. However, similarly to published literature, cancer treatment, including cytotoxic chemotherapy, was not significantly associated with COVID-19 mortality27,28,32,34,41.

We then performed multivariable logistic regression to assess whether the increased mortality observed in patients with hematologic versus solid malignancy was independent of potential confounding effects from smoking history, poor ECOG performance and active cancer. In this fully adjusted analysis, hematologic malignancy was strongly associated with mortality in comparison to solid cancer (odds ratio (OR) = 3.3, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–10.8, P = 0.048) (Table 2). Similar results were observed in time-to-event analyses using Kaplan–Meier methods (Fig. 2a; median overall survival (OS) not reached for patients with solid cancer versus 47 d for patients with hematologic cancer; P = 0.030) and Cox regression models (Table 2; hazard ratio (HR) = 2.56, 95% CI 1.19–5.54, P = 0.017). Moreover, patients with hematologic cancer had higher levels of some inflammatory markers on admission laboratory testing, including ferritin, IL-6 and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). We also assessed viral persistence in 43 patients with repeat RT–PCR testing (37 solid and six hematologic). Both patients with hematologic cancer and patients with solid cancer had prolonged viral clearance, with some greater than 60 d (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d and Supplementary Table 3). Altogether, hematologic malignancy was an independent risk factor of death, with signs of a dysregulated inflammatory response.

a, Kaplan–Meier curve for COVID-19 survival of patients with solid (n = 77) and hematologic (n = 22) cancer. Cox regression-computed HR for mortality in hematologic versus solid cancer, adjusted for age, gender, smoking status, active cancer status and ECOG performance status. b, Ferritin (P = 0.036), IL-6 (P = 0.034) and LDH (P = 0.001) in patients with solid (n = 62) and hematologic (n = 15) cancer hospitalized for COVID-19. All—significance determined by two-sided Mann–Whitney test: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Median and 95% CI are shown. Heme, hematologic.

Impaired SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in hematologic cancer

To determine whether patients with cancer who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 might exhibit an altered immune landscape, we leveraged an observational study of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 at the University of Pennsylvania Health System where blood was collected (MESSI-COVID)14. This analysis included 130 patients with flow cytometric and/or serologic analysis. Twenty-two patients had active cancer (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), including patients undergoing cancer-directed therapies such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy or B cell-directed therapies (Supplementary Table 6). Patients with active cancer were older and predominantly female; both groups had a similar time frame of symptom onset and disease severity (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 4). However, patients with cancer had a higher all-cause mortality (36.4% versus 11.1%; Fig. 3a), consistent with our COPE cohort and other reported cohorts21,24,27,28.

a, Demographic and mortality data for the MESSI cohort at the University of Pennsylvania. b, Relative levels of SARS-CoV-2 IgG (No Cancer versus Heme, P = 0.001; Solid versus Heme, P = 0.007) and IgM (No Cancer versus Heme, P = 0.003; No Cancer versus Solid, P = 0.03); patients with solid (n = 14) and hematologic (n = 7) cancer and patients without cancer (n = 108). c, Left, global UMAP projection of lymphocyte populations for all 45 patients pooled. Right, hierarchical clustering of EMD using Pearson correlation, calculated pairwise for lymphocyte populations. d, UMAP projection of concatenated lymphocyte populations for each EMD cluster. Yellow: high density; black: low density. e, Heat map showing expression patterns of various markers, stratified by EMD cluster. Heat scale calculated as column z-score of MFI. f, Mortality (P = 0.02), disease severity and SARS-CoV-2 antibody data, stratified by EMD cluster (Cluster 5 n = 5; Clusters 1, 2, 3 and 4 n = 40). Mortality significance was determined by the Pearson chi-square test. Severity assessed with the NIH ordinal scale for COVID-19 clinical severity (1: Death; 8: Normal Activity)14. g, UMAP projections of concatenated lymphocyte populations for solid cancer, hematologic cancer and patients without cancer. h, CD8, CD4 (No Cancer versus Heme, P= 0.003; Solid versus Heme, P = 0.01) and B cell (No Cancer versus Heme, P = 0.008; No Cancer versus Solid, P = 0.03; Solid versus Heme, P = 0.02) frequencies in healthy donors (n = 33), patients without cancer (n = 108), patients with solid cancer (n = 7) and patients with hematologic cancer (n = 4). i, UMAP projection of non-naive CD8 T cell clusters identified by FlowSOM. j, Top, UMAP projections of non-naive CD8 T cells for patients with cancer and patients without cancer. Bottom, UMAP projections indicating HLA-DR and CD38 protein expression on non-naive CD8 T cells for all patients pooled. k, Frequency of activated FlowSOM clusters in patients with HD (n = 30), patients without cancer (n = 110) and patients with cancer (n = 8) (P = 0.03). l, Representative flow plots and frequency of HLA-DR and CD38 co-expression in patients with HD (n = 30), patients without cancer (n = 110), patients with solid cancer (n = 7) and patients with hematologic cancer (n = 3) (gated on non-naive CD8) (No Cancer versus Heme, P < 0.0001; Solid versus Heme, P = 0.02). All—significance determined by two-sided Mann–Whitney test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. Median and 95% CI are shown. HD, healthy donors; Heme, hematologic; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

As recovery from COVID-19 results in immunologic memory in the form of antibodies and memory B cells43, we hypothesized that the observed poor outcomes in patients with active cancer might be associated with a defect in SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral immunity. Patients with cancer had significantly decreased SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM antibodies than patients without cancer (Extended Data Fig. 2a). This was largely due to patients with hematologic cancer, most (6/7) of whom had IgM and IgG levels below the cutoff of positivity of 0.48 arbitrary units (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 2b), whereas patients with solid cancer had IgG and IgM antibody responses that were more similar to patients without cancer (Fig. 3b).

T cell-depleted phenotype associated with COVID-19 mortality

Patients who recover from COVID-19 also exhibit SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses43,44. We, therefore, performed exploratory high-dimensional analysis on the lymphocyte compartment of 45 patients, including 44 patients with COVID-19 (36 patients without cancer, six patients with solid cancer and two patients with hematologic cancer) and one control patient without COVID-19. Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) representation of 27-parameter flow cytometry data highlighted discrete islands of CD4 and CD8 T cells and CD19+ B cells (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 3a). We subsequently used the earth mover’s distance (EMD) metric45 to calculate the distance between the UMAP projections for every pair of patients. Clustering on EMD values identified five clusters of patients with similar lymphocyte profiles (Fig. 3c). Differences among these clusters of patients were driven by both the distribution (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 3b) and phenotype (Fig. 3e) of CD4, CD8 and B cells. EMD Cluster 1 was defined by depleted CD4 and B cells, increased CD8 T cells and increased activation and effector markers, including PD-1, CX3CR1, Ki67 and HLA-DR (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 3b). EMD Cluster 3 had decreased T cells and B cells, with an inactivated immune profile, and EMD Cluster 5 was depleted of both CD4 and CD8 T cells but had preserved B cells. In contrast, EMD Cluster 4 was defined by robust CCR7+CD27+ memory CD4 T cell responses and heterogenous B cell responses. EMD Cluster 2 had the most balanced responses, with CD4, CD8 and B cells represented (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 3b). We then correlated these five patterns of immune responses with clinical and serological variables. Patients in EMD Cluster 5 with depleted T cells had the highest mortality and disease severity, despite generating SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM and IgG antibodies (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 5d). In contrast, EMD Clusters 2 and 4, with robust CD4 and/or CD8 T cell responses, had the lowest mortality and a low disease severity (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 5d). These findings suggest a key role for T cell immunity in facilitating recovery from acute COVID-19, even in the presence of intact humoral immunity.

Distinct immune landscape in hematologic cancer

We next explored the role of cancer subtype on immune phenotype. Four of the six patients with solid cancer were in EMD Cluster 2, with a balanced immune phenotype (Fig. 3e). In contrast, both patients with hematologic cancer were in EMD Cluster 1, which had marked depletion of CD4 and B cells. Indeed, UMAP projections showed that, whereas patients with solid cancer had an immune landscape similar to patients without cancer, the two patients with hematologic cancer demonstrated loss of islands associated with CD4 and B cells (Fig. 3g). We then extended this analysis by measuring the frequency and phenotype of key lymphocyte populations in the entire MESSI-COVID cohort and healthy donor controls. Patients with COVID-19 and hematologic cancer had a significantly lower frequency of CD4 and B cells than patients with solid cancer, patients without cancer and healthy donors without COVID-19 (Fig. 3h). As T follicular helper (Tfh) cells and plasmablasts are critical in the generation of effective antibody responses, we assessed circulating Tfh and plasmablast responses. Although limited by sample size, patients with hematologic cancer had low circulating Tfh (PD1+CXCR5+) and plasmablast (CD19+CD27hiCD38hi) responses and decreased CD138 expression (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Thus, patients with hematologic malignancy appear to have quantitative defects in CD4 and B cells that might be required for effective SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody responses.

As patients with hematologic cancer had a preserved frequency of CD8 T cells, we performed FlowSOM clustering analysis on non-naive CD8 T cells from 118 patients with COVID-19 and 30 healthy donors and visualized the clusters using UMAP. UMAP clearly separated CX3CR1- and Tbet-expressing effector cells from memory CD8 T cells expressing CD27 and TCF-1 (Extended Data Fig. 4b and Fig. 3i). The effector island was composed of CD45RAloCD27lo effector memory cells (Clusters 2 and 3) and CD45RA+ TEMRA cells (Cluster 1). The memory island was composed of CCR7lo transitional memory (Cluster 5), effector memory (Clusters 7 and 8) and CCR7hi central memory (Cluster 9) cells. Activated cells, characterized by high HLA-DR, CD38 and Ki67 expression, were identified in Clusters 3, 4 and 5 (Extended Data Fig. 4c).

We then compared the landscape of CD8 T cells in patients with and without cancer. CD8 T cell subsets, including central memory, effector memory, transitional memory and TEMRA, were similar between patients with and without cancer (Extended Data Fig. 4d). However, UMAP representation of non-naive CD8 data demonstrated preferential enrichment of cells expressing HLA-DR and CD38 in patients with cancer compared to patients without cancer (Fig. 3j). Indeed, patients with cancer had higher frequencies of activated HLA-DR-, CD38- and Ki67-expressing FlowSOM clusters (Clusters 3, 4 and 5) than patients without cancer and healthy donors (Fig. 3k and Extended Data Fig. 4e). When stratified by cancer type, the increased HLA-DR and CD38 expression was restricted to the patients with hematologic cancer; patients with solid cancer and those without cancer had similar levels of activation (Fig. 3l). Altogether, patients with solid cancer and COVID-19 had an immune landscape similar to patients without cancer with COVID-19. In contrast, patients with hematologic malignancies had defects in CD4 T cells, B cells and humoral immunity but preserved and highly activated CD8 T cells. These observations raised the possibility that CD8 T cell activation might potentially compensate for blunted humoral immune responses in patients with hematologic malignancies.

CD8 T cells influence survival in patients with hematologic cancer

To more rigorously explore the role of T and B cell immunity in patients with cancer who were infected with SARS-CoV-2, we examined a cohort of patients with cancer who were hospitalized with COVID-19 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), which included a larger number of patients with hematologic malignancies, including those treated with B cell-depleting therapy. The median age of the MSKCC cohort was 65 years, and, in contrast to the MESSI cohort at the University of Pennsylvania, 81% of the cohort was White (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). Consistent with the Penn COPE and MESSI cohorts, patients with hematologic cancer did poorly, with a mortality rate of 44.4% (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 7). In the MSKCC cohort, both CD4 and CD8 T cells were significantly decreased in patients with active solid and hematologic cancer compared to patients in clinical remission (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Moreover, despite the fact that a substantial number of patients with hematologic cancer from the MSKCC cohort received convalescent plasma (Supplementary Table 7), they had a significant defect in SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM responses compared to patients with solid cancer (Extended Data Fig. 5b). This was independent of disease severity and viral load (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d).

a, Demographic and mortality data of the MSKCC cohort. b, Left, hierarchical clustering of EMD using the Pearson correlation, calculated pairwise for lymphocyte populations; right, global UMAP projection of lymphocyte populations pooled. c, UMAP projection of concatenated lymphocyte populations for each EMD cluster. Yellow: high density; black: low density. d, Mortality (Cluster 5 n = 7; Clusters 1, 2 and 4 n = 50), severity and RT–PCR cycle threshold (Cluster 1 n = 14; Cluster 2 n = 5; Cluster 4 n = 24; Cluster 5 n = 6) (lower Ct: higher viral load) stratified by EMD cluster. Mortality significance determined by the Pearson chi-square test. e, Relative levels of SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM of patients with recent cancer treatments (solid tx n = 9; heme αCD20 n = 7; heme other tx n = 5). f, Absolute CD8 and CD4 T cell in patients treated with B cell-depleting therapy (alive n = 7; dead n = 4). g, Absolute CD8 (P = 0.01) and CD4 T cell counts and B cell counts (P = 0.003) counts in patients with hematologic cancer (alive n = 17; dead n = 18). h, Kaplan–Meier curve for survival in patients with hematologic cancer stratified by CD8 T cell counts (threshold = 55.9; log-rank HR) (≥55.9 n = 28; <55.9 n = 13). CD8 count threshold determined by CART analysis. i, Left, representative ELISpot plates from two patients after stimulation with no peptide, EBV and SARS-CoV-2 consensus peptide pools; right, IFN-γ and IL-2 (P = 0.02) SFU per million PBMCs in patients with hematologic cancer (n = 13). Significance was determined by the two-sided Wilcoxon test. j, Proportion of patients with hematologic cancer with detectable IFN-γ SFU, after background subtraction (no peptide). Significance was determined by the chi-square test. k, Simple linear regression between IFN-γ SFU and percent activated CD8 T cells in patients with hematologic cancer who recovered from COVID-19 (n = 6). All—significance determined by two-sided Mann–Whitney test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. Median and 95% CI are shown. Ct, cycle threshold; Heme, hematologic; tx, treatment.

EMD and clustering of flow cytometry data from 20 patients with solid cancer, 31 patients with hematologic cancer and six patients in remission identified four immune phenotypes (Fig. 4b,c and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b) that corresponded to the immune phenotypes 1, 2, 4 and 5 identified in the Penn-MESSI cohort (Fig. 3c,d). The Penn phenotype 3, the only cluster that did not have patients with cancer, was not identified in the MSKCC cohort. Consistent with the Penn data, MSKCC EMD Cluster 5, with depleted of CD4 and CD8 T cells and preserved B cells, had the highest mortality of 71% and was associated with a high disease severity and viral load (Fig. 4d).

Patients in the MSKCC cohort with solid cancer were present in all four clusters, with most in Cluster 4, whereas patients with hematologic cancer were predominantly in Clusters 1 and 4 and absent from Cluster 2 (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Intriguingly, the clinical outcomes of patients with immune phenotype 4 was the greatest contributor to the overall mortality difference between patients with solid and hematologic cancers. Patients with hematologic cancer with phenotype 4 had a mortality of 62% versus 9% in patients with solid cancer (Extended Data Fig. 7c), with a corresponding higher viral load (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Immune phenotype 4 was characterized by robust CD4 responses and decreased, but still present, CD8 responses (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Within immune phenotype 4, patients with solid and hematologic cancers had similar CD4 and CD8 T cell counts (Extended Data Fig. 7e). However, patients with hematologic cancer had near-complete abrogation of B cells (phenotype 4A) that corresponded with a mortality rate of 62% (Extended Data Fig. 7c,f). In contrast, patients with solid cancer had intact B cell counts (phenotype 4B) with a mortality of 9% (Extended Data Fig. 7c,f). Thus, in a setting with similar CD4 and CD8 T cell numbers, B cell depletion was associated with higher mortality.

Anti-CD20 (αCD20) therapy with rituximab or obinutuzumab-containing regimens depleted circulating B cells and significantly impaired SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM responses (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 8a). αCD20 was not associated with quantitative changes in CD4 and CD8 T cells. However, patients treated with αCD20 therapy exhibited significant reductions in CD4 and CD8 naive and memory T cells, with a relative skewing toward effector differentiation and an activated HLA-DR+CD38+ phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). These changes were not seen in patients with hematologic cancer without COVID-19 who received αCD20 (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e). Notably, despite the loss of B cells and humoral immunity, αCD20 therapy was not associated with increased mortality, disease severity or viral load when compared to chemotherapy or observation (Extended Data Fig. 9a).

We sought to understand why αCD20 therapy was not associated with greater mortality in these patients. Patients treated with αCD20 therapy were restricted to immune phenotypes 1 and 4, characterized by depleted B cells (Extended Data Fig. 9b). However, phenotype 1, characterized by preserved CD8 T cells, was associated with a lower mortality (Extended Data Fig. 9c). Indeed, patients treated with αCD20 who survived their COVID-19 hospitalization had higher CD8 T cell counts (Fig. 4f) and lower viral load (Extended Data Fig. 9d). We extended these analyses to other patients with hematologic cancer, including those on chemotherapy who also had quantitative (Extended Data Fig. 8a), and possibly qualitative, B cell defects. Patients with hematologic cancer who survived had higher CD8 T cell counts (Fig. 4g), which was not observed in patients with solid cancer (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Conversely, CD4 T cell counts were not associated with mortality, and higher B cell counts were associated with increased mortality (Extended Data Fig. 9e and Fig. 4g). Classification and regression tree (CART) analysis identified a CD8 T cell level that was predictive of survival after COVID-19 in patients with hematologic cancer (Fig. 4h). Thus, patients with hematologic cancer, in the setting of defective humoral immunity, were more highly dependent on adequate CD8 T cell counts than patients with solid cancer.

Finally, to assess the antigen-specificity of T cell responses in patients with cancer who were infected with SARS-CoV-2, we stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 13 patients with hematologic cancer and ten patients with solid cancer using major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I- and MHC-II-restricted SARS-CoV-2 and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) peptide pools and measured IFN-γ and IL-2 responses using enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assays (Extended Data Fig. 10a). After background (no-peptide) subtraction, ten of 13 (77%) patients with hematologic cancer had SARS-CoV-2-specific IL-2 and/or IFN-γ responses (Fig. 4i), including eight of eight (100%) patients treated with αCD20 (Fig. 4j and Extended Data Fig. 10b). In general, these SARS-CoV-2-specific responses were greater in magnitude than EBV-specific responses (Fig. 4i), and patients with hematologic cancer had greater SARS-CoV-2 antigen-specific T cell responses than patients with solid cancer (Extended Data Fig. 10c). Moreover, in patients with hematologic cancer who recovered from COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2-specific IFN-γ responses correlated with the frequency of HLA-DR+CD38+ CD8 T cells (Fig. 4k) but not with HLA-DR+CD38+ CD4 T cells (Extended Data Fig. 10d). This correlation was not seen in patients who died (Extended Data Fig. 10e). Taken together, these findings suggest that, for patients with hematologic cancer who recover from COVID-19, increased peripheral CD8 T cell activation might reflect an appropriate induction of SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses. In contrast, peripheral CD8 T cell activation might be uncoupled from SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell responses in patients who ultimately die from disease. These data do not exclude a role for SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 T cells, which has been associated with control of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients without cancer and in mouse models46,47.

Discussion

A notable feature of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the dramatic heterogeneity in clinical presentations and outcomes, yet mechanistic explanations for the wide variance in disease severity have remained elusive. We speculated that investigating both the clinical outcomes and immunologic profile of patients with cancer might provide valuable insight into how the arms of the immune system contribute to viral control and mortality during acute COVID-19. Our work reveals several key insights. First, we established, in a prospective clinical cohort, that hematologic malignancy is an independent predictor of COVID-19 mortality after adjusting for ECOG performance and disease status. Given that patients with a poor ECOG performance status are known to have higher COVID-19 mortality35, this work extends the findings of a recent meta-analysis that reported an increased COVID-19 mortality rate in patients with hematologic cancer48 by demonstrating that the increased mortality risk seen in hematologic cancer was, in fact, driven by cancer subtype rather than differences in patient characteristics.

Second, using high-dimensional analyses, we define immune phenotypes associated with mortality in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients wth cancer. In particular, patients with depleted T cell responses had the highest mortality, regardless of the presence of B cell responses. Thus, humoral immunity alone is often insufficient in acute COVID-19. This is consistent with recent data demonstrating the importance of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells in viral clearance and limiting disease severity46,47. In fact, greater B cell responses were associated with higher mortality in both solid and liquid cancers. B cell responses might be a marker of disease severity, as seen with plasmablasts14,18 and neutrophils18,49,50 in severe COVID-19. Alternatively, some components of the B cell and humoral responses might be aberrant and pathogenic, as might be the case with autoantibodies targeting type I interferons in severe COVID-19 (ref. 51). CD8 T cells are known to be critical for viral clearance, particularly in response to higher viral inocula52. Our data suggest that CD8 T cells play a key role in limiting SARS-CoV-2, even in the absence of humoral immunity. This is consistent with recent data demonstrating the presence of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 T cell responses in acute and convalescent individuals46,53,54,55,56, and that CD8 T cells contribute to protection from SARS-CoV-2 rechallenge in the setting of waning antibody responses in convalescent macaques57.

The compensatory role of T cells was restricted to patients with hematologic, but not solid, malignancies. Thus, CD8 T cells likely play an important role in the setting of quantitative and qualitative B cell dysfunction in patients with lymphoma, multiple myeloma and leukemia undergoing αCD20 therapy, chemotherapy or Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibition. Indeed, we could identify SARS-COV-2-specific T cell responses in most patients with hematologic cancer, including all patients treated with αCD20, and they were generally greater in magnitude than in patients with solid cancer. These SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses correlated with peripheral activated CD8 T cells, but not CD4 T cells, in patients who recovered from infection. These data suggest a role for SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8 T cells in controlling acute infection, although more definitive studies are needed. These observations also have important translational implications. CD8 T cell counts might inform on the need for closer monitoring and a lower threshold for hospitalization in patients with COVID-19 and hematologic malignancy. Furthermore, the clinical benefit of dexamethasone, which demonstrated an overall mortality benefit in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, but is known to suppress CD8 T cell responses58, should be investigated further in patients who recently received αCD20 therapy.

Our findings do not exclude a key role for humoral immunity in protection from COVID-19 mortality. Indeed, although patients with solid cancer had a cellular and humoral immune landscape that was similar to patients without cancer59, patients with hematologic cancer had substantial defects in B cells and humoral immunity. Our analysis revealed that blunted humoral immune responses resulted in an increased mortality rate in patients with diminished, but not absent, CD8 T cell responses. Thus, B cells and associated antibody responses play an important role in acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, and CD8 T cell responses that are normally sufficient might no longer be adequate in the setting of compromised humoral immunity. This is consistent with published data demonstrating that uncoordinated immune responses in the elderly was associated with severe disease and poor outcomes46.

Importantly, both B cell-depleting therapies and cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, which can compromise the T cell compartment, are mainstays of lymphoma therapy. Both are administered, often in combination, with curative intent for patients with aggressive lymphoma but also for debulking or palliation in patients with indolent lymphoma. Based on our data, we suggest that oncologists and patients considering treatment regimens that combine B cell depletion with cytotoxic agents carefully weigh the associated increased risk of immune dysregulation against the benefit of disease control when making an educated decision on whether to initiate such treatments, particularly in non-curative settings.

Finally, our finding that CD8 T cell immunity is critical for survival in patients with hematologic malignancy and COVID-19 has implications for the vaccination of these patients. The current Food and Drug Administration-approved COVID-19 mRNA vaccines induce robust CD8 T cell responses in addition to humoral responses60,61,62,63. Our findings suggest that vaccination of patients with hematologic cancer might provide protection through T cell immunity, despite the likely absence of humoral responses. Ultimately, understanding how the immune response relates to disease severity, cancer type and cancer treatment will provide important insight into the pathogenesis of and protective immunity from SARS-CoV-2, which might have implications for the development and prioritization of therapeutics and vaccines in subpopulations of patients with cancer.

Methods

General design/patient selection

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study of patients with cancer hospitalized with COVID-19 (UPCC 06920). The University of Pennsylvania and Lancaster General Health institutional review boards (IRBs) approved this project, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Adult patients with a current or previous diagnosis of cancer and hospitalized with a probable or confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19, as defined by World Health Organization (WHO) criteria64, within the University of Pennsylvania Health System between April 28, 2020, and September 15, 2020, were approached for consent. Participating hospitals included the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Presbyterian Hospital, Pennsylvania Hospital and Lancaster General Hospital. The WHO’s definition of a probable case of SARS-CoV-2 is based on patients having a combination of high-risk symptoms, suspect chest imaging or death in the setting of respiratory distress and confirmed or probable contact to COVID-19, whereas a confirmed case is defined by someone with positive nucleic acid amplification testing or SARS-CoV-2 antigen testing in the setting of symptoms or probable COVID-19 contact64. We enrolled 114 patients across all four hospitals; 14 patients were excluded from the analyses owing to either low suspicion for COVID-19 infection or benign tumor diagnosis. Our final cohort of 100 patients included 48 females with a median age of 68 years (interquartile range (IQR) 57.5–77.5 years). The index date was defined as the first date of hospitalization within the health system for probable or confirmed COVID-19. Repeat hospitalizations within 7 d of discharge were considered within the index admission. Patients who died before being approached for consent were retrospectively enrolled. Patients were followed from the index date to 30 d after their discharge or until death by any cause. This study was approved by the IRBs of all participating sites.

Data collection

Baseline characteristics, including patient factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, smoking history and body mass index (BMI)) and cancer factors (tumor type, most recent treatment, ECOG performance status and active cancer status), as well as COVID-19-related clinical factors, including change in levels of care, complications, treatments such as need for mechanical ventilation, laboratory values (complete blood counts with differentials and inflammatory markers including LDH, C-reactive protein, ferritin and IL-6), and final disposition were extracted by trained research personnel using standardized abstraction protocols. Active cancer status was defined by diagnosis or treatment within 6 months of admission date. Cancer treatment status was determined by the most recent treatment within 3 months before admission date.

The primary study endpoint was all-cause mortality from hospital admission until 30 d of hospital discharge. Disease severity was categorized using a modified version of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ordinal scale including all post-hospitalization categories: 1: hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen but requiring ongoing medical care; 2: hospitalized requiring any supplemental oxygen; 3: hospitalized requiring non-invasive mechanical ventilation or use of high-flow oxygen devices; 4: hospitalized receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; and 5: death65. Disease severity was assessed every 7 d throughout a patient’s admission.

Statistical analysis

Cohort characteristics were compared using standard descriptive statistics. One-time imputation of missing values for ECOG performance status was done using the predicted mean value from an ordinal logistic model (proportional odds) of complete data. The ordinal model was fitted with forward stepwise selection, with entry at P = 0.1 and removal at P = 0.2, using clinical variables expected to be correlated with ECOG performance status. Those variables included several items in the Charlson Comorbidity Index and other clinical variables.

Univariate analyses examined demographic and clinical variables and cancer subtype (hematologic versus solid cancer) as predictors of death within 30 d of discharge and of ICU admission. ORs and 95% CIs were used to generate the forest plot illustration. Baseline laboratory tests were compared by cancer type using Mann–Whitney tests, and available RT–PCR data were used to determine length of RT–PCR positivity by cancer type.

Rates of ICU admission and death were calculated for the overall cohort and stratified by cancer subtype. A multivariate logistic model was used to examine the adjusted effect of solid versus hematologic designation. Covariates included demographic variables of age and sex (race was omitted for missing data). Covariates also included clinical variables that attained a P value of 0.1 in the univariate analyses. The final model included age, sex, smoking status, active disease status and ECOG performance status. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was also performed to determine the association between cancer type and mortality and identically adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, active cancer status and ECOG performance status. OS was measured from date of hospitalization to last follow-up or death; median OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method; and differences by cancer subtype were compared using the log-rank test.

Immune profiling of patients hospitalized for COVID-19—MESSI

Information on clinical cohort, sample processing and flow cytometry is described in Mathew et al.14. Briefly, patients admitted to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test were screened and approached for informed consent within 3 d of hospitalization. Peripheral blood was collected from all patients, and clinical data were abstracted from the electronic medical record into standardized case report forms. All participants or their surrogates provided informed consent in accordance with protocols approved by the regional ethical research boards and the Declaration of Helsinki. Methods for PBMC processing, flow cytometry and antibodies used were previously described14. Missing data, including antibody and flow cytometry data, are largely driven by sample availability and are assumed to be unrelated to the immunologic endpoint of interest and other variables.

Serologic enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were completed using plates coated with the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, as previously described66. Briefly, before testing, plasma and serum samples were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 1 h. Plates were read at an optical density (OD) of 450 nm using the SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Background OD values from the plates coated with PBS were subtracted from the OD values from plates coated with recombinant protein. Each plate included serial dilutions of the IgG monoclonal antibody CR3022, which is reactive to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, as a positive control to adjust for inter-assay variability. Plasma and serum antibody concentrations were reported as arbitrary units relative to the CR3022 monoclonal antibody. A cutoff of 0.48 arbitrary units was established from a 2019 cohort of pre-pandemic individuals and used for defining seropositivity.

Flow cytometry and statistical analysis

Flow cytometry data from Mathew et al.14 were analyzed. Briefly, samples were acquired on a five-laser BD FACSymphony A5. Up to 2 × 106 live PBMCs were acquired per each sample. During the early sample acquisition period, three antibodies in the flow panel were changed. Samples of three patients with cancer and 12 patients without cancer were stained using this earlier flow panel. Flow features were visually assessed for batch variations against data from the later flow panel. The three patients with cancer were included with the rest of the cohort when batch effects were determined to have little effect on confidence in gated populations. These three patients with cancer were excluded in analysis of cell populations defined by proteins associated with the three changed antibodies. Owing to the heterogeneity of clinical and flow cytometric data, non-parametric tests of association were used throughout the study. Tests of association between unpaired continuous variables were performed by the Mann–Whitney test. Tests of association between paired continuous variables were performed by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. Tests of association between binary variables across two groups were performed using the Pearson chi-square test. All tests were performed using a nominal significance threshold of P < 0.05 with Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software) and Excel (Microsoft). CART analysis was performed using the R package rpart.

High-dimensional data analysis of flow cytometry data

UMAP analyses were conducted using the R package uwot. FlowSOM analyses were performed on Cytobank (https://cytobank.org). Lymphocytes and non-naive CD8 T cells were analyzed separately. UMAP analysis was performed using equal downsampling of 10,000 cells from each FCS file in lymphocytes and 1,500 cells in non-naive CD8 T cells, with a nearest neighbors of 15, minimum distance of 0.01, number of components of 2 and a Euclidean metric. The FCS files were then fed into the FlowSOM clustering algorithm. A new self-organizing map (SOM) was generated for both lymphocytes and non-naive CD8 using hierarchical consensus clustering. For each SOM, 225 clusters and ten metaclusters were identified. For lymphocytes, the following markers were used in the UMAP and FlowSOM analyses: CD45RA, PD-1, IgD, CXCR5, CD8, CD19, CD3, CD16, CD138, Eomes, TCF-1, CD38, CD95, CCR7, CD21, Ki-67, CD27, CD4, CX3CR1, CD39, Tbet, HLA-DR and CD20. For non-naive CD8 T cells, the following markers were used: CD45RA, PD-1, CXCR5, CD16, Eomes, TCF-1, CD38, CCR7, Ki-67, CD27, CX3CR1, CD39, Tbet and HLA-DR. Clusters with less than 0.5% frequency were excluded from downstream analysis. Heat maps were created using R package pheatmap. To group individuals based on lymphocyte landscape, pairwise EMD values were calculated on the lymphocyte UMAP axes using the emdist package in R. Resulting scores were hierarchically clustered using the hclust function in the stats package in R.

Immune profiling of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 at MSKCC

Patients admitted to MSKCC with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test were eligible for inclusion. The project was approved by the IRB of MSKCC, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. For inpatients, clinical data were abstracted from the electronic medical record into standardized case report forms. Clinical laboratory data were abstracted from the date closest to research blood collection. Peripheral blood was collected into BD Horizon Dri tubes (BD, cat. no. 625642). Immunophenotyping of PBMCs via flow cytometry was performed in the MSKCC clinical laboratory. The lymphocyte panel included CD45 FITC (BD, 340664, clone 2D1, 1:40), CD56+ 16 PE (BD 340705, clone B73.1, 1:40; BD 340724, clone NCAM 16.2, 1:40), CD4 PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD 341653, clone SK3, 1:200), CD45RA PE-Cy7 (BD 649457, clone L48, 1:80), CD19 APC (BD 340722, clone SJ25C1, 1:80), CD8 APC-H7 (BD 641409, clone SK1, 1:80) and CD3 BV 421 (BD 562426, clone UCHT1, 1:80). The naive/effector T panel included CD45 FITC (BD 340664, clone 2D1, 1:40), CCR7 PE (BD 560765, clone 150503, 1:80), CD4 PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD 341653, clone SK3, 1:200), CD38 APC (BioLegend, 303510, clone HIT2, 1:20), HLA-DR V500 (BD 561224, clone G46-6, 1:80), CD45RA PE-Cy7 (BD 649457, clone L48, 1:80), CD8 APC-H7 (BD 641409, clone SK1, 1:80) and CD3 BV 421 (BD 562426, clone UCHT1, 1:80). The immune phenotypes were based on NIH vaccine consensus panels and the Human Immunology Project67. Samples were acquired on a BD FACSCanto using FACSDiva software.

ELISpot

ELIspot assays: 200,000 PBMCs per well were plated on Human IFN-γ/IL-2 Double-Color ELISpot plates (ImmunoSpot) in the presence of anti-human CD28 (0.2 ug ml−1) and with or without peptide (Miltenyi PepTivator EBV consensus or SARS-CoV-2 Select) at a final concentration of 0.3 µM. The EBV consensus pool (130-099-764) contains 43 MHC-I and MHC-II peptides derived from 13 EBV proteins, whereas the SARS-CoV-2 Select peptide pool (130-127-309) contains 88 lyophilized MHC-I- and MHC-II-restricted peptides derived from the whole proteome of SARS-CoV-2. Plates were incubated in a 37 °C humidified incubator for 18 h, after which plates were stained as per manufacturer instructions and quantified using an automated ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer. Results are expressed in spot-forming units (SFU) per 106 PBMCs.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Flow cytometry data collected for the MESSI-COVID cohort were deposited in FlowRepository (http://flowrepository.org/id/FR-FCM-Z3XT). Raw data are included in Supplementary Table 10. External data requests can be directed to the corresponding authors, who will respond within 1 week and help facilitate the request. Access to clinical datasets for the COPE study, clinical flow cytometry and clinical metadata from the MSKCC cohort will be available based on approval through the IRBs of the University of Pennsylvania and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and might be subject to patient privacy.

References

Blanco-Melo, D. et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell 181, 1036–1045 (2020).

Hadjadj, J. et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science 369, 718–724 (2020).

Arunachalam, P. S. et al. Systems biological assessment of immunity to mild versus severe COVID-19 infection in humans. Science 369, 1210–1220 (2020).

Yale IMPACT Team et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature 584, 463–469 (2020).

Lee, J. S. et al. Immunophenotyping of COVID-19 and influenza highlights the role of type I interferons in development of severe COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaabd1554 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 2620–2629 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020).

Tan, L. et al. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: a descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 33 (2020).

Zhao, Q. et al. Lymphopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 96, 131–135 (2020).

Qin, C. et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 762–768 (2020).

Laing, A. G. et al. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat. Med. 26, 1623–1635 (2020).

Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E. J. et al. Complex immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure. Cell Host Microbe 27, 992–1000 (2020).

Mann, E. R. et al. Longitudinal immune profiling reveals key myeloid signatures associated with COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabd6197 (2020).

Mathew, D. et al. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science 369, eabc8511 (2020).

Su, Y. et al. Multi-omics resolves a sharp disease-state shift between mild and moderate COVID-19. Cell 183, 1479–1495 (2020).

De Biasi, S. et al. Marked T cell activation, senescence, exhaustion and skewing towards TH17 in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Nat. Commun. 11, 3434 (2020).

Xu, Z. et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 420–422 (2020).

Kuri-Cervantes, L. et al. Comprehensive mapping of immune perturbations associated with severe COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabd7114 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 2027–2034 (2020).

Long, Q.-X. et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26, 845–848 (2020).

Rugge, M., Zorzi, M. & Guzzinati, S. SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Italian Veneto region: adverse outcomes in patients with cancer. Nat. Cancer 1, 784–788 (2020).

Assaad, S. et al. High mortality rate in cancer patients with symptoms of COVID-19 with or without detectable SARS-COV-2 on RT–PCR. Eur. J. Cancer 135, 251–259 (2020).

Miyashita, H. & Kuno, T. Prognosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in patients with HIV infection in New York City. HIV Med. 22. e1–e2 (2020).

Dai, M. et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-COV-2: a multi-center study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 10, 783–791 (2020).

Saini, K. S. et al. Mortality in patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and pooled analysis of 52 studies. Eur. J. Cancer 139, 43–50 (2020).

Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (2020; accessed 19 October 2020).

Mehta, V. et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov. 10, 935–941 (2020).

Lee, L. Y. W. et al. COVID-19 prevalence and mortality in patients with cancer and the effect of primary tumour subtype and patient demographics: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1309–1316 (2020).

Mato, A. R. et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with CLL: a multicenter international experience. Blood 136, 1134–1143 (2020).

Chari, A. et al. Clinical features associated with COVID-19 outcome in multiple myeloma: first results from the International Myeloma Society data set. Blood 136, 3033–3040 (2020).

Lamure, S. et al. Determinants of outcome in Covid-19 hospitalized patients with lymphoma: a retrospective multicentric cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 27, 100549 (2020).

Lee, L. Y. W. et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 395, 1919–1926 (2020).

Albiges, L. et al. Determinants of the outcomes of patients with cancer infected with SARS-CoV-2: results from the Gustave Roussy cohort. Nat. Cancer 1, 965–975 (2020).

Kuderer, N. M. et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet 375, 1907–1918 (2020).

Grivas, P. et al. Association of clinical factors and recent anti-cancer therapy with COVID-19 severity among patients with cancer: a report from the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium. Ann. Oncol. 32, 787–800 (2021).

West, H. J. & Jin, J. O. Performance status in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 1, 998 (2015).

Wu, Z. & McGoogan, J. M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 323, 1239–1242 (2020).

Petrilli, C. M. et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 369, m1966 (2020).

Williamson, E. J. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584, 430–436 (2020).

Zhou, F. et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395, 1054–1062 (2020).

Jee, J. et al. Chemotherapy and COVID-19 outcomes in patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3538–3546 (2020).

Robilotti, E. V. et al. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat. Med. 26, 1218–1223 (2020).

Sette, A. & Crotty, S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell 184, 861–880 (2021).

Karlsson, A. C., Humbert, M. & Buggert, M. The known unknowns of T cell immunity to COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabe8063 (2020).

Orlova, D. Y. et al. Earth mover’s distance (EMD): a true metric for comparing biomarker expression levels in cell populations. PLoS ONE 11, e0151859 (2016).

Rydyznski Moderbacher, C. et al. Antigen-specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell 183, 996–1012 (2020).

Sun, J. et al. Generation of a broadly useful model for COVID-19 pathogenesis, vaccination, and treatment. Cell 182, 734–743 (2020).

Vijenthira, A. et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3377 patients. Blood 136, 2881–2892 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. Immune phenotyping based on the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and IgG level predicts disease severity and outcome for patients with COVID-19. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7, 157 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts critical illness patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in the early stage. J. Transl. Med. 18, 206 (2020).

Bastard, P. et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 370, eabd4585 (2020).

Weidt, G. et al. CD8+ T lymphocyte-mediated antiviral immunity in mice as a result of injection of recombinant viral proteins. J. Immunol. 153, 2554–2561 (1994).

Sekine, T. et al. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell 183, 158–168 (2020).

Peng, Y. et al. Broad and strong memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells induced by SARS-CoV-2 in UK convalescent individuals following COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1336–1345 (2020).

Kared, H. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cell responses in convalescent COVID-19 individuals. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e145476 (2021).

Ni, L. et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral and cellular immunity in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Immunity 52, 971–977 (2020).

McMahan, K. et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature 590, 630–634 (2021).

Cook, A. M., McDonnell, A. M., Lake, R. A. & Nowak, A. K. Dexamethasone co-medication in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy causes substantial immunomodulatory effects with implications for chemo-immunotherapy strategies. Oncoimmunology 5, e1066062 (2016).

Abdul-Jawad, S. et al. Acute immune signatures and their legacies in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infected cancer patients. Cancer Cell 39, 257–275 (2021).

Sadoff, J. et al. Interim results of a phase 1–2a trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2034201 (2021).

Corbett, K. S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571 (2020).

Sahin, U. et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature 586, 594–599 (2020).

Monin, L. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00213-8 (2021).

World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 Case Definition. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Surveillance_Case_Definition-2020.2 (2020).

Beigel, J. H. et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1813–1826 (2020).

Flannery, D. D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among parturient women in Philadelphia. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabd5709 (2020).

Maecker, H. T., McCoy, J. P. & Nussenblatt, R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the human immunology project. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 191–200 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank patients and blood donors, their families and surrogates and medical personnel. In addition, we thank the University of Pennsylvania COVID Processing Unit: a unit of individuals from diverse laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania who volunteered time and effort to enable the study of patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic (Supplementary Table 9). Funding: A.C.H. was funded by grant CA230157 from the NIH and funding from the Tara Miller Foundation. D.O. was funded by T32 T32CA009140. L.A.V. is funded by a Mentored Clinical Scientist Career Development Award from NIAID/NIH (K08 AI136660). E.B. was funded by T32 T32-CA-09679. N.J.M. was supported by NIH HL137006 and HL137915. D.M. was funded by T32 CA009140. J.R.G. is a Cancer Research Institute-Mark Foundation Fellow. A.L.G. was supported by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research Award. J.R.G., J.E.W., C.A., A.C.H. and E.J.W. are supported by the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, which supports the Cancer Immunology program at the University of Pennsylvania. E.J.W. was supported by NIH grants AI155577, AI112521, AI082630, AI201085, AI123539 and AI117950 and funding from the Allen Institute for Immunology. S.A.V. was supported by funding from the Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Foundation, the Conrad Hilton Foundation and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. S.D. was funded, in part, by T32CA009512 and an ASCO Young Investigator Award. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.H., R.M., S.V. and E.M.B. conceived the project. A.C.H., S.V. and N.A.H. designed all experiments. A.C.H., R.M., E.M.B., A.M.D. and I.P.M. conceived the Penn COPE cohort. E.M.B., J.R., F.P., O.O., K.N., C.Z., M.G., A.R.W., C.A.G.I., E.M.K., C.R., K.R.B., S.T. and C.W. enrolled patients and collected data for COPE. E.M.B., R.M., A.M.D. and A.C.H. designed data and statistical analysis for COPE. P.W. performed statistical analysis for COPE. N.J.M. conceived the Penn MESSI-COVID clinical cohort. A.R.W., C.A.G.I., O.O., R.S.A., T.G.D., T.J., H.M.G., J.P.R. and N.J.M. enrolled patients and collected data for MESSI-COVID. N.A.H., A.E.B. and J.Y.K. performed downstream flow cytometry analysis for MESSI-COVID. S.G., M.E.W., C.M.M. and S.E.H. analyzed COVID-19 patient plasma and provided antibody data. N.A.H., J.R.G., A.R.G., C.A. and D.A.O. performed computational and statistical analyses. C.A. compiled clinical metadata for MESSI-COVID. J.R.G., D.O. and C.A. analyzed clinical metadata for MESSI-COVID. S.V. and J.W. conceived the MSKCC cohort. S.V., A.K., A.W., S.D. and S.B. provided clinical samples from the MSKCC cohort. P.M. performed downstream flow cytometry analysis. N.E.B. performed quantitative PCR experiments for COVID viral load. N.A.H. and A.C.H. compiled figures. K.N.M., A.L.G., L.S., R.H.V., J.D.W. and E.J.W. provided intellectual input. E.M.B., S.V., R.M. and A.C.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.A.V. is a consultant for Immunai and ADC Therapeutics. A.C.H. is a consultant for Immunai and has received research support from Bristol Myers Squibb. R.H.V. reports having received consulting fees from Medimmune and Verastem and research funding from Fibrogen, Janssen and Eli Lilly. R.H.V. is an inventor on licensed patents relating to cancer cellular immunotherapy and cancer vaccines and receives royalties from Children’s Hospital Boston for a licensed research-only monoclonal antibody. J.W. is serving as a consultant for Adaptive Biotechnologies, Advaxis, Amgen, Apricity, Array BioPharma, Ascentage Pharma, Astellas, Bayer, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Chugai, Elucida, Eli Lilly, F-Star, Genentech, Imvaq, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Kleo Pharmaceuticals, Linnaeus, MedImmune, Merck, Neon Therapeutics, Northern Biologics, Ono, Polaris Pharma, Polynoma, PsiOxus, PureTech, Recepta, Takara Bio, Trieza, Sellas Life Sciences, Serametrix, Surface Oncology, Syndax and Synthologic. J.W. received research support from Bristol Myers Squibb, MedImmune, Merck and Genentech and has equity in Potenza Therapeutics, Tizona Pharmaceuticals, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Elucida, Imvaq, BeiGene, Trieza and Linnaeus. J.V.C. is serving as a consultant for Sanofi-Genzyme and Bristol Myers Squibb. A.M.D. is supported with an honorarium from Pfizer (2016 and 2018), consulting fees from Context Therapeutics (2018), Novartis (2016) and Calithera (2016) and institutional research support from Novartis, Pfizer, Genetech, Calithera and Menarini. R.M. has served as a consultant for Seattle Genetics, Astellas and Roche; has received research funding from Merck; and received funding from Flatiron Health for speaking on Real-World Evidence. A.L.G. received research funding from Novartis, Janssen, Tmunity and CRISPR Therapeutics and honoraria from Janssen and GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Reviewer recognition statement Nature Medicine thanks Toni Choueiri, Eui-Cheol Shin and Robert Thimme for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Saheli Sadanand was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Inflammatory markers, blood cell counts, and viral load in cancer patients with COVID-19.

Clinical laboratory values for (a) inflammatory markers and (b) cell counts in solid (n = 62) and hematologic (n = 21) cancer patients. Repeat SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing results (c) from first positive test to last performed test and (d) from first positive test to last positive test. (All) Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test.

Extended Data Fig. 2 SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels in cancer patients with COVID-19.

a, Relative levels of SARS-CoV-2 IgG (p = 0.02) and IgM (p = 0.0008) in non-cancer (n = 108) and cancer (n = 21) patients. b, Relative IgG levels in cancer patients. Each dot represents a cancer patient (Heme: Red; Solid: Yellow). (All) Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Dimensionality reduction and EMD clustering of MESSI cohort.

a, UMAP projections of lymphocytes with indicated protein expression. b, Frequencies of CD19+, CD3+, CD3+ CD8+, and CD3+ CD4+ cells of patients in each EMD cluster (Cluster 1 n = 7; Cluster 2 n = 16; Cluster 3 n = 6; Cluster 4 n = 10; Cluster 5 n = 5). (All) Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cellular phenotyping of COVID-19 patients with cancer.

a, Frequencies of circulating T follicular helper cells (cTfh), plasmablasts (No Cancer vs. Heme, p = 0.0001; Solid vs. Heme, p = 0.006), and CD138 expression on plasmablasts (HD n = 33; non-cancer n = 108; solid cancer n = 7; heme cancer n = 3). b, UMAP projection of non-naïve CD8 T cells with indicated protein expression. c, Heatmap showing expression patterns of various markers, stratified by FlowSOM clusters. Heat scale calculated as column z-score of MFI. d, Frequencies of CD8 subsets: naive (CD45RA+ CD27+ CCR7+), central memory (CD45RA-CD27+ CCR7+), transition memory (CD45RA-CD27+ CCR7-) (p < 0.0001), effector memory (CD45RA-CD27-CCR7-), and TEMRA (CD45RA+ CD27-CCR7-) (p = 0.002) (HD n = 33; non-cancer n = 108; cancer n = 9). e, (Left) HLA-DR and CD38 co-expression in concatenated activated clusters (3, 4, and 5) and associated UMAP localization. (Right) Frequency of clusters 3 (p = 0.03) and 5 (HD n = 30; non-cancer n = 110; cancer n = 8). (All) Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cellular, serologic, and clinical features in solid and hematologic cancer patients with COVID-19.

a, Absolute counts of CD4 (Remission vs. Heme, p = 0.01; Remission vs. Solid, p = 0.02), CD8 (p = 0.02), and CD19 (Remission vs. Heme, p = 0.008; Solid vs. Heme, p = 0.0003) expression in remission (n = 11), solid cancer (n = 23), and hematologic cancer (n = 41) patients. b, Relative levels of SARS-CoV-2 IgG (p = 0.003) and IgM (p = 0.0007) in solid (n = 11) and hematologic cancer (n = 14) patients. c, Severity (NIH ordinal scale for COVID-19 clinical severity) and RT-PCR cycle threshold (remission n = 9; solid n = 25; heme n = 28) (Lower Ct: Higher viral load). d, NIH ordinal scale for COVID-19 clinical severity. (All) Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Dimensionality reduction and EMD clustering of MSKCC cohort.

a, UMAP projections of lymphocytes with indicated protein expression. b, Absolute counts of CD19+, CD3+, CD3+ CD8+, and CD3+ CD4+ cells of patients in each EMD cluster (Cluster 1 n = 18; Cluster 2 n = 6; Cluster 4 n = 26; Cluster 5 n = 7). (All) Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 7 EMD Cluster 4 drives differences in mortality between hematologic and solid cancer patients.

a, EMD cluster distributions of heme and solid cancer patients. b, Number of patients with hematologic, solid, and remission cancer status within each EMD cluster. c, Mortality of patients within each EMD cluster for hematologic and solid cancers. d, RT-PCR cycle threshold of solid and heme cancer patients in EMD cluster 4 (solid n = 11; heme n = 11) (p = 0.02). e, Absolute CD8 and CD4 T cell counts for subjects in EMD cluster 4 stratified by solid (n = 11) and heme (n = 13) cancer. f, Global UMAP projections of lymphocytes for subjects in EMD cluster 4: (Left) Hematologic cancer; (Middle) Solid cancer. (Right) Absolute B cell counts for subjects in EMD cluster 4 stratified by solid (n = 11) and heme (n = 13) cancer (p = 0.004). (All) Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Effect of cancer treatment on T cell differentiation in COVID-19.

a, Absolute counts of CD4, CD8, and CD19 expressing cells. Frequencies of (b) CD4 and (c) CD8 T cell subsets in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade therapies, chemotherapies, and B cell depleting therapies. Frequencies of (d) CD4 and (e) CD8 T cell subsets in heme cancer patients with and without COVID-19, and with and without αCD20. Naive (CD45RA+ CCR7+), CM (CD45RA-CCR7+), EM (CD45RA-CCR7-), TEMRA (CD45RA+ CCR7-). (All) Remission n = 11, obs n = 12, chemo only n = 9, solid ICB n = 7, heme αCD20 n = 10, non-COVID heme no tx n = 5, and non-COVID heme αCD20 n = 5. Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test. Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Association of mortality with cell counts and viral load.

a, Mortality, severity, and RT-PCR cycle threshold stratified by cancer treatment (remission n = 9; solid obs n = 6; solid tx n = 19; heme obs n = 5; heme chemo n = 4; heme αCD20 n = 10). Severity assessed with NIH ordinal scale for COVID-19 clinical severity. b, Recent cancer treatment of patients in each EMD cluster. c, Mortality of patients treated with B cell depleting therapy in EMD cluster 1 (red) and EMD cluster 4 (blue). d, RT-PCR cycle threshold of patients treated with αCD20 therapy (alive n = 7; dead n = 3). e, Absolute counts of CD8, CD4, and CD19 (p = 0.004) cells in solid cancer patients (alive n = 16; dead n = 7). (All) Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test: **p < 0.01. Median and 95% CI shown.

Extended Data Fig. 10 EBV and SARS-CoV-2 ELISpot in COVID-19 cancer patients.

ELISpot was performed after stimulation of PBMC with no peptide, EBV, and SARS-CoV-2 peptide pools. a, IFN-γ (No Peptide vs. COVID, p = 0.003) and IL-2 (No Peptide vs. COVID, p = 0.03; EBV vs. COVID, p = 0.02) spot forming units (SFU) per million PBMC in heme cancer patients (n = 13). Significance determined by Wilcoxon test. b, IFN-γ SFU per million PBMC in heme cancer patients treated with (n = 8) and without (n = 5) αCD20 with no-peptide background condition subtracted. c, IFN-γ and IL-2 SFU between solid (n = 10) and heme (n = 13) cancer patients. Simple linear regression between IFN-γ SFU per million cells and percent activated CD4 (d) and CD8 (e) T cells in alive (n = 8) and dead (n = 5) heme cancer patients. (All) Significance determined by two-sided Mann Whitney test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Median and 95% CI shown.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–9.

Supplementary Data 1

MESSI cohort: immune and clinical data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bange, E.M., Han, N.A., Wileyto, P. et al. CD8+ T cells contribute to survival in patients with COVID-19 and hematologic cancer. Nat Med 27, 1280–1289 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01386-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01386-7

This article is cited by

-

IgG antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and its influencing factors in lymphoma patients

BMC Immunology (2024)

-

Expansion of memory Vδ2 T cells following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination revealed by temporal single-cell transcriptomics

npj Vaccines (2024)

-

An mRNA vaccine encoding the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain protects mice from various Omicron variants

npj Vaccines (2024)

-

Mucosal vaccine-induced cross-reactive CD8+ T cells protect against SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1.5 respiratory tract infection

Nature Immunology (2024)

-

Longevity of the humoral and cellular responses after SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccinations in immunocompromised patients

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2024)