Abstract

The burden of malaria is heavily concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where cases and deaths associated with COVID-19 are rising1. In response, countries are implementing societal measures aimed at curtailing transmission of SARS-CoV-22,3. Despite these measures, the COVID-19 epidemic could still result in millions of deaths as local health facilities become overwhelmed4. Advances in malaria control this century have been largely due to distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs)5, with many SSA countries having planned campaigns for 2020. In the present study, we use COVID-19 and malaria transmission models to estimate the impact of disruption of malaria prevention activities and other core health services under four different COVID-19 epidemic scenarios. If activities are halted, the malaria burden in 2020 could be more than double that of 2019. In Nigeria alone, reducing case management for 6 months and delaying LLIN campaigns could result in 81,000 (44,000–119,000) additional deaths. Mitigating these negative impacts is achievable, and LLIN distributions in particular should be prioritized alongside access to antimalarial treatments to prevent substantial malaria epidemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Globally, COVID-19 has the potential to overburden health systems. Interventions aimed at curbing transmission of SARS-CoV-2, such as restrictions to movement, absenteeism, behavioral changes, closure of institutions and interruption of supply chains, are also expected to result in malaria prevention activities being scaled back6,7. These antimalarial activities include mass distribution of LLINs, which are the most effective current tool for reducing malaria5. LLINs are typically distributed centrally within a community at gatherings that could be canceled or poorly attended as COVID-19 spreads. Other important focal preventive measures, such as seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) and indoor residual spraying of insecticide (IRS), which are conducted house to house, could also be reduced. The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasized that all routine prevention and case management activities should be continued to the fullest extent possible8; however, early statistical modeling suggests that disrupting LLIN distribution and malaria treatment could have a substantial impact on the malaria burden in Africa6.

In the present study, we attempt to quantify the potential impact of the spread of COVID-19 on Plasmodium falciparum malaria morbidity and mortality in Nigeria and across SSA using mathematical models of COVID-194 and malaria9. We assume that one disease does not directly influence the transmission or severity of the other, but that COVID-19 impacts malaria via the response to the epidemic and its repercussions on health systems. Predictions of the timing and magnitude of COVID-19 epidemics across African countries are highly uncertain and will vary according to how individual countries respond to COVID-19. We use illustrative examples to show how different COVID-19 mitigation and suppression strategies could influence malaria burden. A summary of the main findings, limitations and policy implications of our study is shown in Table 1. The pervasive and potentially large consequences of COVID-19 on African communities, such as increased poverty, malnutrition and social instability, which themselves can influence malaria burden, are not captured.

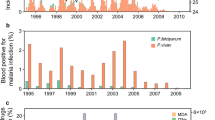

We consider four scenarios for the COVID-19 epidemic that will determine the period of malaria service interruption (Fig. 1): (1) unmitigated COVID-19 epidemic—although unlikely to occur, this scenario illustrates how a rapid epidemic would be highly disruptive to malaria services, but for a limited period; (2) mitigation—social contact is reduced but the effective reproduction number (Rt) remains >1, causing a longer-lasting COVID-19 epidemic; (3) suppression—social distancing reducing Rt < 1 remains in place until alternative strategies to contain COVID-19 are available, with malaria activities potentially disrupted for a year; and (4) suppression lift—suppression is sustained but then subsequently lifted resulting in a resurgence of the COVID-19 epidemic.

a, The COVID-19 epidemic and the number of people needing oxygen support per week for four different COVID-19 scenarios: an unmitigated epidemic (red), mitigation (blue), continued suppression (green) and suppression lift (purple). The thin dotted horizontal gray line indicates estimated health-care capacity for a typical African country. The thick black horizontal line beneath each figure shows the period when COVID-19 mitigation or suppression activities are assumed to be in operation. b, The assumed duration of interruption where COVID-19 interventions affect different malaria prevention activities (IRS, LLINs and SMC) or case management of clinical cases, with the level of this disruption presented in Table 2. c, The predicted deaths due to COVID-19 per week in each scenario. d, Predicted malaria deaths per week for each scenario (colored lines) and for the counter-factual where there was no COVID-19-induced disruption (black lines). The top colored lines indicate a scenario in which nets and SMC are halted and case management reduced by half (see Supplementary Table 3, row 1), whereas the bottom dashed colored lines show the most well-managed scenario (see Supplementary Table 3, row 3).

We assume that malaria services could be interrupted if COVID-19 mitigation or suppression activities are ongoing or if health-care capacity is exceeded due to COVID-19. The impact of different levels of malaria service interruption is investigated. LLIN campaigns can either continue as normal or be delayed for a year, and clinical case treatments and SMC remain as planned, are reduced or are halted.

Currently, it is unclear how COVID-19 will spread in Africa, although all four COVID-19 scenarios are projected to result in substantial additional deaths from malaria. Implementing COVID-19 mitigation strategies substantially reduces COVID-19 mortality but the prolonged period of health system disruption risks considerably increased malaria deaths (Table 2). This is especially evident in Nigeria, where the longer malaria service disruption due to a mitigated (for 6 months) or suppressed (for 1 year) COVID-19 epidemic overlaps with the malaria transmission season, which peaks around September (Fig. 1). Considering the effect of the COVID-19 mitigation scenario across SSA over the coming year, if SMC and IRS were halted, the treatment of clinical cases was reduced by half for the next 6 months from 1 May 2020, and if LLIN campaigns due in 2020 were canceled, malaria cases are estimated to increase by 206 million (95% uncertainty interval (UI) = 157–254 million) (see Supplementary Table 1), and malaria deaths by 379,000 (95% UI = 221,000–537,000) (Table 2), with a corresponding additional 19 (95% UI = 11–26) million life-years lost (see Supplementary Table 2).

Many countries are pursuing strategies to suppress COVID-19 to minimize deaths1. Our results illustrate that, even if COVID-19 suppression is well managed and LLIN campaigns remain unaffected, with SMC coverage and case management reduced by 50% relative to the norm, prolonged service interruption could increase malaria deaths in Nigeria by approximately 42,000 (95% UI = 22,000–62,000) (see Supplementary Table 3) and across SSA by 200,000 (95% UI = 115,000–285,000) (Table 2). The impact of disruption to malaria services lasting ≥6 months from 1 May 2020 will be greatest in countries where the malaria transmission is high at the end of the year (see Extended Data Fig. 1). Failure to maintain a COVID-19 suppression strategy is likely to lead to a large resurgence, potentially resulting in worse outcomes for both COVID-19 and malaria.

Our findings demonstrate that provision of LLINs is critical. Of the 47 malaria-endemic countries in SSA, 27 were due LLIN campaigns in 2020, with delivery of 228 million LLINs expected (https://netmappingproject.allianceformalariaprevention.com). Across SSA, maintaining routine LLIN distribution in a COVID-19 mitigation scenario is predicted to halve deaths attributable to malaria (Table 2). This year, many LLINs in SSA will be 3 years old and have diminished efficacy due to insecticide loss and physical degradation10. The increased spread of mosquitoes resistant to LLIN insecticides may exacerbate this problem11. Effects can vary substantially within countries according to existing LLIN protection, and whether the COVID-19 epidemic will delay scheduled LLIN campaigns (Fig. 2a and see also Extended Data Fig. 2).

a, Estimated additional deaths per million people when all malaria interventions (LLIN campaigns, SMC and clinical treatment of cases) are halted for 6 months relative to normal service in the absence of COVID-19 for each administrative region (maps for other COVID-19 scenarios are presented in Extended Data Fig. 2). b, Reduction in additional malaria deaths by expanding the age of those eligible for SMC in regions within the Sahel where it was conducted in 2019 relative to all malaria interventions canceled (Table 2, row 11: red bars) or LLIN distributions continue while clinical treatment ceases (Table 2, row 8: blue bars). Absolute values are shown in Supplementary Table 7. c, Reduction in additional malaria deaths by introducing a single round of MDA (using the prophylactic with a similar profile to amodiaquine + sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine) for regions where SMC is not currently conducted (see Supplementary Table 9). MDA is assumed to be implemented at the optimal time, before the transmission peak for each administration unit. In both SMC and MDA scenarios, we assume that 70% of the respective populations receive the intervention. Negative values indicate that there are fewer malaria deaths than would have been predicted if routine antimalarial interventions had been maintained without a COVID-19 epidemic. The map was prepared using GADM v.3.6 (https://gadm.org/).

Disruption to case management increases the case fatality ratio (see Supplementary Table 4) and is predicted to have a similar effect on morbidity to canceling LLIN campaigns if services are stopped for equivalent time periods (illustrated in the COVID-19 suppression scenario when both LLINs and clinical treatment are interrupted for 1 year; Table 2). Maintaining 50% of the normal level of treatment over a 6-month period could still prevent up to 100,000 deaths if prevention activities ceased. In Nigeria, case management was estimated to be particularly important due to mass LLIN campaigns scheduled in just 7 of the 37 states in 2020. SMC is currently implemented in the Sahel region of West Africa, which reduces the continental effects of this antimalarial activity. However, the consequences of canceling SMC in operational regions are predicted to be large. A successful 2020 SMC campaign (in regions covered in 2019) is predicted to reduce deaths by 40% in a COVID-19 mitigation scenario if LLIN distributions and case management are also halted (see Supplementary Table 5).

There is considerable uncertainty about how COVID-19 will spread in Africa and how countries will respond2,12. A lower basic reproduction number, R0, would slow the epidemic and reduce COVID-19 deaths, yet potentially increase malaria mortality as a result of prolonged antimalarial service interruption. Social-distancing measures may reduce the spread of COVID-19 in Africa, but it is unclear for how long these measures will be maintained and what their effects on health-care capacity will be (see Extended Data Fig. 3). This uncertainty substantially influences not only estimates of COVID-19 mortality but also the interruption of malaria services. For example, in Nigeria, if COVID-19 spreads with an R0 of 2.5 compared with 3, service interruption in the COVID-19 mitigation scenario would be extended from 6 months to 9 months to prevent a resurgence of COVID-19 (see Extended Data Fig. 3), which would increase malaria deaths by ~17%, even if LLINs were distributed and some case management was maintained (see Supplementary Table 6). Overall, the effects of COVID-19 on malaria are predicted to be greater than early estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO)6. This is probably due to the inclusion of SMC and IRS in our analysis, which have a substantial public health impact. The model also mechanistically captures differences in population immunity (determined by the history of malaria infection) and the impact of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes, both of which could increase malaria resurgence. Nevertheless, the numbers of deaths presented here should be considered illustrative because there are large uncertainties in how COVID-19 will spread and communities respond.

After the 2014 West African Ebola crisis, the WHO now recommends the use of mass drug administration (MDA) to prevent excess mortality during complex emergencies13. We explored the extent to which introducing or extending chemoprevention could mitigate excess malaria deaths during the COVID-19 epidemic. If LLIN campaigns in 2020 are delayed during a mitigated COVID-19 scenario, increasing the target age of SMC across the Sahel region from children aged <5 years to children aged <10 and 15 years could save 13,500 and 22,500 lives, respectively (Fig. 2b, and see also Extended Data Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 7). Almost half the lives saved would be in Nigeria SMC regions (see Supplementary Table 8). Outside current SMC areas, a single round of MDA to 70% of the population is predicted to avert up to 266 deaths per million people over the next year (see Extended Data Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 9) depending on the region in which it is implemented (see Extended Data Figs. 4b and 5 and Supplementary Table 10). Such emergency measures will depend on the feasibility of increasing the supply of appropriate drugs in areas where SMC interventions are not currently planned.

Symptoms of both COVID-19 and malaria include fever, which can confuse diagnosis in settings with limited testing for both diseases. In COVID-19 cases, the likelihood of developing fever increases with age (Fig. 3a), whereas malaria fever declines with age. The percentage of fevers attributable to malaria compared with COVID-19 is predicted to vary temporally according to the synchrony of the two epidemics (Fig. 3b,c). Furthermore, the proportion of febrile children in whom fever is attributable to malaria is likely to be higher than shown in our results, due to the data on COVID-19 fever in children primarily being sourced from hospital settings (see Supplementary Data 1). Many countries are advising that suspected COVID-19 cases should self-isolate (https://www.acaps.org/covid19-government-measures-dataset), which might further reduce malaria diagnosis. Providing simple age-based guidelines could substantially reduce malaria burden if malaria tests are unavailable. For example, presumptively treating 70% of febrile children aged <5, 10 and 15 years with antimalarials could save 122,000, 159,000 and 178,000 lives over the next year, respectively. Further work is needed to consider the implications of this strategy on the supply of drugs and burden of nonmalarial fevers14. Adhering to social-distancing guidelines will also remain critical because many people who are infected with COVID-19 could also harbor malaria parasites. For example, our modeled results indicate that, at the malaria transmission season peak in Mali (an example of a country with seasonal transmission; Fig. 3b), in individuals aged >15 years, 30% of those infected with COVID-19 would also have malaria parasites, and therefore may not self-isolate if diagnosed with malaria as the cause of their fever.

a, A systematic review of the literature showing how the percentage of COVID-19 cases with fever varies with respect to age. Points show published estimates colored according to the cohort in which they were observed: patients admitted to hospital (red), patients admitted to ICUs (green), contacts of known cases (blue) or a mixed cohort (purple). A summary of all data including precise estimates and sample sizes for each study are provided in Supplementary Table 13. The solid line shows best-fit logistic regression line fit to all groups, and the shaded region indicates 95% confidence interval estimates in the mean. Vertical colored lines show the interquartile range for the proportion of fevers (when available) whereas the horizontal colored lines show the range of ages reported in each cohort. b, Left column figures show estimates of how the proportion of malaria fevers relative to COVID-19 fevers (that is, proportion of fevers due to malaria divided by malaria + COVID-19 fevers) varies over time; the right column shows the proportion of COVID-19 cases co-infected with asymptomatic malaria. The top row shows predictions for seasonal Mali; the bottom row shows the more perennial Uganda. In all panels in b, black lines indicate prevalence of malaria (as detected by microscopy) and dashed lines show COVID-19 prevalence; colored lines indicate age of group in years, 0–5 (red), 5–15 (green) or >15 (blue) years of age (scaling COVID-19 fevers by age using the regression line presented in a). c, Country-level mean estimates of the fraction of fevers due to malaria compared with those due to malaria and/or COVID-19 in children aged <5 years in July 2020. Maps were prepared using GADM v.3.6 (https://gadm.org).

The rapid global spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has demonstrated the global vulnerability to new infectious diseases. Continued malaria prevention and treatment programs will be essential to reduce pressure on health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

COVID-19 transmission model

Potential COVID-19 trajectories were produced through a modeling framework from Walker et al.4. We used an age-structured, susceptible, exposed, infectious, then susceptible again model of transmission with age-specific patterns of disease severity captured according to age-dependent probabilities that infection leads to disease requiring hospitalization (and the need for treatment with high-pressure oxygen), to more severe disease requiring intensive care and subsequently to mortality. Model parameters are based on an analysis of age-specific severity and infection:mortality ratios observed in China and the United Kingdom4,15,16 because comparable data from SSA are currently not available. To produce simulations representative of a malaria-endemic setting, the model was calibrated to typical social contact patterns observed within surveys in SSA, which show less substantial declines in contact rates by age17, and the demography of Nigeria, our case study and the country with the highest burden of malaria globally18. Our projections therefore incorporate a lower per-infection demand for health care such as oxygen and mechanical ventilation driven by the younger populations within malaria-endemic settings. Life-years lost were calculated under this demography using the corresponding life tables.

To capture the probable constraints within a health system, we contrasted this demand for health care with a representative level of supply using the median estimated provision of hospital beds and intensive care units (ICUs) for a low-income country4. This threshold was chosen on the basis that, although many countries in SSA are lower–middle income and therefore likely to have a lower total number of hospital beds and ICUs, access to high-pressure oxygen and mechanical ventilation within hospitals is lower than within equivalent high-income settings19. During the course of a projected scenario, as health-care capacity is exceeded, individuals requiring either mechanical ventilation or high-pressure oxygen who are unable to receive these interventions are then subject to a substantially higher degree of mortality, leading to excess mortality during time periods in which health systems are overwhelmed (for full details, code and parameterization, see https://github.com/mrc-ide/squire).

Representative scenarios were simulated using a basic reproduction number, R0, of 3 representing a 3.5-day doubling time in cases and deaths reflecting many trajectories currently observed globally20. A full list of the parameter values is provided in Supplementary Table 11. Once a threshold of 0.1 deaths per million (approximately reflecting the COVID-19 mortality observed in many countries in Africa to date) has been exceeded, the pandemic trajectory follows four potential scenarios:

-

1.

‘Unmitigated’: no direct action is taken but contact rates are reduced by 20% relative to baseline, according to assumed behavior change given the pandemic even in the absence of specific, coordinated public health interventions.

-

2.

‘Mitigation’: through combinations of isolation and social distancing, contact rates are reduced by 45% for 6 months, after which infections fall to low levels and contact rates return to pre-pandemic levels. This scenario approximates the maximum reduction in the final size of the epidemic that can be achieved while generating sufficient levels of immunity capable of preventing a second wave once measures have been lifted (assuming infection leads to high levels of immunity from reinfection). It thus produces the lowest final numbers of COVID-19 infections of the three strategies that do not involve indefinite suppression.

-

3.

‘Indefinite suppression’: stringent suppression-targeting interventions are implemented to reduce contact rates by 75%, and these are maintained indefinitely in the hope that a pharmaceutical intervention (for example, effective vaccine) is developed and deployed. We run this scenario for 12 months. (After this period, lifting suppression without such a pharmaceutical intervention would lead to a second wave of equivalent size as in the ‘Suppression lift’ scenario.)

-

4.

‘Suppression lift’: the stringent ‘lockdown’-type interventions implemented by many countries are assumed to reduce contact rates by 75%. This reduction is maintained for 2 months, then lifted, and contact rates return to 80% of their pre-pandemic levels for the remainder of the epidemic.

These scenarios represent four possible projections of what could happen to the epidemic, not what policy strategy was adopted by the different countries. The number of deaths associated with COVID-19 between 1 May 2020 and 30 April 2021 is estimated, for African populations at risk of malaria, to provide a direct comparison with the predictions of malaria mortality.

It is assumed that malaria control is impeded by either the health system being overwhelmed or because mitigation or suppression social-distancing measures are in place. The health system is classified as being overwhelmed when the model estimates that the number of people currently requiring noncritical care in hospitals for COVID-19 is 50% more than current hospital capacity (here defined for Africa as 1,281 per million people4). The timing and duration of service interruption for the different COVID-19 scenarios are shown in the second row of Extended Data Fig. 1.

The trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa is highly uncertain. To illustrate this uncertainty two different sensitivity analyses are conducted: (1) a univariate sensitivity analysis that shows how R0 influences the severity of the epidemic and (2) a multivariate sensitivity analysis that varies all parameters to indicate the wider uncertainty.

In the univariate sensitivity analysis we vary R0 between 2.0 and 3.5 to cover the range of estimates currently predicted for the region2,12. This is repeated for the four different COVID-19 scenarios described above. Estimates of the number of people requiring supplementary oxygen over time are presented in Extended Data Fig. 3a. Note that, in the COVID-19 mitigation scenario when R0 < 3, the epidemic is not predicted to have peaked after 6 months when the social-distancing measures are assumed to be lifted (and many people have not been infected). In this scenario, if social-distancing measures are relaxed, then there is predicted to be a large rebound epidemic with a high death rate as hospitals are overwhelmed (similar to the suppression lift scenario). This means that lower R0 simulations may counterintuitively have higher deaths due to COVID-19. An alternative assumption could be that social-distancing measures in the mitigation scenario are extended for 9 or 12 months. These simulations indicate a lower peaked epidemic with fewer deaths. Both possible mitigation scenarios with different periods of social distancing are presented in Extended Data Fig. 3a.

In the multivariate sensitivity analysis, we vary all the main parameters within the model for the four different COVID-19 scenarios. These include R0, the effectiveness of social distancing at reducing the contact rate, parameters determining the duration of hospitalization and the different severity parameters of the disease (the probability of death if critical care is required but not received; probability of death if hospitalized and oxygen is available; probability of death if hospitalized, but oxygen is not available; and probability of death if hospitalization is required but no hospital bed is available). A total of 500 parameter draws were independently sampled using a log-scaled triangular distribution centered around 1, which spanned the range of values presented in Supplementary Table 11. To capture uncertainty in the infection fatality ratio and how this varies by age, the probabilities of death reported in Supplementary Table 11 were applied to 500 posteriors sampled from the fitted joint posterior distribution of Verity et al.16. This provides 500 different estimates of the magnitude of the infection fatality rate and how it increases with age. These values were then used to parameterize 500 different simulations of the COVID-19 transmission model. For each run, the period of potential malaria service interruption was calculated from the introduction of mitigation measures to the time when health care is no longer over capacity (see Extended Data Fig. 3b–e). Results show how varying the parameters of the COVID-19 mitigation scenario can produce COVID-19 trajectories similar to the other three COVID-19 scenarios considered. For example, a high R0 generates short periods of service interruption similar to the unmitigated scenario, whereas a low R0 may recreate the period of interruption of either the suppression lift scenario (if social-distancing measures are released after 6 months) or a suppression scenario (if social distancing is maintained for a longer period). The uncertainty in the number of deaths from the multivariate sensitivity analysis was used to estimate the mortality 95% UIs presented in Table 2.

Malaria transmission model

A previously published model of malaria transmission dynamics was used to predict malaria deaths resulting from different COVID-19 scenarios9 (the code is freely available at https://github.com/jamiegriffin/Malaria_simulation). Simulations were run at the administrative 1-unit level (where, for each region, the model is calibrated to capture the seasonality, prevalence, vector composition, treatment coverage and vector control coverage, incorporating levels of pyrethroid resistance in each unit) and results are aggregated across regions according to the size of the population at risk of malaria. Results are presented for the high malaria burden country of Nigeria and for SSA as a whole. For Nigeria, administrative 1-unit level estimates of malaria prevalence, LLIN use, drug treatment, coverage of SMC and the timing of 2020 LLIN campaigns were made available by the National Malaria Elimination Program (NMEP) in Nigeria (see Extended Data Fig. 6). For other regions of SSA, models were parameterized using 2016 malaria prevalence from the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP, https://malariaatlas.org). For all countries, modeled clinical cases were aligned with World Malaria Report median cases18,21. LLIN usage was estimated at the administrative 1-unit level also using MAP estimates, with LLIN usage after campaigns expected to be matched at each subsequent mass campaign. Malaria control depends on insecticide resistance in the local mosquitoes which diminishes the effectiveness of LLINs. This was estimated for each administrative unit from discriminating dose bioassays collated by the WHO over time (projecting forward to 2020) and combined with results from experimental hut trials to estimate the LLIN epidemiological impact22,23. Malaria transmission seasonality was estimated by local rainfall trends averaged over 8 years and offset by 35 d to reflect mosquito abundance (National Weather Service, Climate Prediction Center (cited 24 March 2016)24,25). The estimated proportion of clinical cases receiving prompt treatment was based on Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data and is assumed to remain at estimated 2016 levels26. Malaria deaths across all ages were estimated using the modeled number of severe cases, scaled by the assumed proportion of severe cases resulting in mortality both in and outside the hospital setting, and adjusted by the location-specific proportion of clinical cases receiving treatment9. Estimates of malaria deaths in 2018 were scaled to align with World Malaria Report median deaths for 2018 for the same region18.

Different levels of malaria prevention and treatment interruption are considered together. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on malaria is determined solely by the duration of service interruption, which vary for malaria prevention and treatment activities according to which of the four different COVID-19 scenarios is considered. The duration of these different periods of interruption of malaria services is presented in Fig. 1 and is chosen to represent the range of durations observed in the multivariate sensitivity analysis of the COVID-19 model (see Extended Data Fig. 3d). We assume that changing the human-to-human contact rate that influences the trajectory of the COVID-19 epidemic has no impact on malaria transmission other than through the duration of service interruption. The possible impact of COVID-19 on LLIN distribution is assumed to start at the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic because most African countries initiated some mitigation or suppression activities. The increase in malaria cases caused by COVID-19 will depend on the time since the last LLIN campaign, because older nets are probably less effective due to loss of insecticide23. Aging of LLINs may be exacerbated by the spread of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes, because they may overcome the concentrations of insecticide on the LLINs earlier than susceptible mosquitoes11,23. All LLINs before 2020 are assumed to be standard pyrethroid-only LLINs, because the numbers of alternative LLINs procured in 2019 are very low. In Nigeria, the year and month of LLIN campaigns are known (or approximated for future mass distributions) at the administrative 1-unit level (state) providing greater resolution. For elsewhere in Africa, the Alliance for Malaria Prevention (https://netmappingproject.allianceformalariaprevention.com) estimates were used to calculate the timings of campaigns and the proportion of LLINs distributed in 2018 and 2019, and due in 2020 by country because it is unclear when or where the different campaigns were delivered at a subnational level. Different simulations were run for each administrative unit distributing LLINs at the appropriate year and season. Overall estimates of clinical cases in the administrative unit were weighted by the proportion of LLINs given out that year. LLIN campaigns due to occur before April 2020 were assumed to have occurred as planned. Those campaigns that were due at a time of COVID-19-induced disruption either went ahead as planned (achieving the same population coverage) or were delayed until a year after they were originally due. LLIN campaigns due in quarters 2–4 in 2020 were assumed to be delayed in the unmitigated, mitigated and suppression lift COVID-19 scenarios. This period of disruption is assumed to be longer than other control interventions, reflecting the high chance of disruption to the LLIN supply chain and difficulties in distributing LLINs to local communities. Standard pyrethroid LLINs were distributed in 2020 unless the region was due to have LLINs with the synergist piperonyl butoxide, and LLIN efficacy estimates were taken from Churcher et al.23. It is assumed that 80% of LLINs are distributed through mass campaigns and the remainder are distributed continually, and that these continual distributions cease if LLIN mass campaigns are delayed.

Uncertainty in the estimated number of clinical cases and deaths and life-years lost was investigated using a multivariate sensitivity analysis. It was not computationally possible to generate full posterior samples for all scenarios presented here. We therefore developed and tested a normal approximation to the posterior distribution for the output metrics.

First, 20 draws from the joint posterior distribution of the fitted transmission model parameters were used to generate 20 uncertainty runs for all 37 states in Nigeria, for each of the COVID-19 and malaria scenarios (see Extended Data Fig. 7). For each uncertainty run, we calculated the additional clinical cases and deaths to generate 95% UIs for Nigeria, and also calculated the coefficient of variation (CV). We then tested the applicability of a normal approximation for uncertainty in other regions, by undertaking a full uncertainty analysis across a smaller subset of 40 first administrative units (10 administrative units from each of Zambia (all provinces included), Mozambique, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Burkina Faso) and comparing the 95% UIs generated for each country to the intervals obtained using a normal distribution approximation with the CV for Nigeria. We found good agreement between the approximation and full uncertainty analysis for the regions tested (see Extended Data Fig. 7). We therefore applied this approach across all runs using the CV from the Nigeria simulations and the additional 40 administrative 1-unit levels to obtain 95% UIs across the results for SSA.

Results are highly sensitive to when mass LLIN campaigns are scheduled to occur. Multiple countries have subnational campaigns and it is unclear where, within the country, LLINs are due to be distributed. To illustrate this uncertainty caused by the timing of LLIN campaigns, we conducted a sensitivity analysis for countries where the location of mass campaigns is unknown by simulating distributions in either 2019 or 2020 (see Supplementary Table 12).

SMC was assumed to be undertaken in the same administrative units covered in 2019 and 70% of children aged <5 years are assumed to be treated, except in Senegal where children up to age 10 years are covered and we assume 70% coverage18. We simulated amodiaquine + sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine as the prophylactic drug delivered for SMC campaigns across three or four rounds, depending on the existing strategy of the country27. The proportion of clinical cases of malaria receiving the appropriate prompt treatment outside the COVID-19 epidemic was estimated based on data extracted from the DHS on the proportion of febrile children who were given medical treatment, and the type of treatment administered (DHS, https://dhsprogram.com). Before 1 May 2020, indoor residual spraying was assumed to take place annually in the same administrative units covered historically (as per 2018)28. During the period of health system interruption, SMC and clinical treatment of cases can reduce to zero, reduce to 50% of the planned level (35% of the target age group are covered for SMC) or continue as before. IRS is assumed to be canceled.

The distribution of drugs either through existing SMC channels or through special MDA projects could be used to reduce the impact of COVID-19 on malaria. Bespoke methods of delivery are being considered to deliver drugs to households while maintaining social distancing. In regions where SMC is carried out, this intervention could be extended from the current target age of children aged <5 years to targeting children aged <10 or 15 years. All other aspects of the SMC campaigns are assumed to remain the same (that is, regions where it is deployed, seasonal timing, number of rounds and coverage within the targeted age group). Outside regions with SMC, a single round of MDA using a drug with a similar profile of prophylactic protection to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine + amodiaquine (in the absence of resistance) is considered. It is assumed to be administered to 70% of the population (either age <5 years or to all ages) with the timing of the MDA aligned for each region to be optimally deployed at the start of the peak transmission season.

We simulated the number of malaria deaths from 1 May 2020 to 30 April 2021, for both the non-COVID-19 scenario and the four COVID-19 scenarios, and for a range of malaria intervention combination strategies. Care should be taken when directly comparing the relative impact of different malaria interventions because they vary in their period of disruption (other than in the suppression scenario). All possible treatment options are considered, although some, such as the halting of all case management for a year, are considered unlikely. Projected deaths were aggregated across regions and presented as the increase in deaths predicted for the different COVID-19 and malaria scenarios relative to the non-COVID-19 scenario for the year. Subnational differences outside Nigeria should be treated with caution. Many countries now have mass LLIN campaigns staggered over multiple years for logistical and financial reasons, and this information on subnational timing of LLIN campaigns was unavailable for all countries other than Nigeria, which can introduce substantial uncertainty (see Supplementary Table 12). Similarly, at a local level, the impact of service disruption would be greater for clinical treatment where clinics treat a high proportion of the local community relative to clinics serving a proportionally lower sample of the community.

The impact of the uncertainty in the R0 for COVID-19 in Africa on malaria mortality is investigated for Nigeria by assuming that the period of service interruption increases from 6 months to 9 months, which is predicted to be required if the COVID-19 R0 reduced from 3.0 to 2.5 (see Supplementary Table 6).

Fever in COVID-19 and malaria

A literature search was conducted to obtain the proportion of fever in COVID-19-positive patients, broken down by age and type of cohort. The search terms ‘covid’ OR ‘SARS-CoV-2’ AND ‘fever’ were used in the PubMed and MEDLINE (Ovid) databases, yielding 384 nonduplicate records. Titles and abstracts of these records were screened for the words ‘child’ or ‘children’, resulting in 28 hits.

Of the 28 papers, 9 were systematic reviews, which were screened for further references. With this, 36 papers were added for extraction. In all, 64 full texts were screened. Eight papers were rejected because either they were in Chinese (n = 5) or they did not provide a breakdown of fever between adults and children (n = 3). Data were extracted from 49 papers for this analysis29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78 (see Supplementary Table 13). Each study examines a different cohort of patients, which may influence the prevalence of fever. In the present study we classify each cohort into those patients (1) admitted to hospital, (2) admitted to ICUs, (3) who are contacts of known cases or (4) in a mixed cohort.

Logistic regression is used to characterize how age influences the prevalence of fever in patients confirmed as having COVID-19. The reporting of fever increased substantially with age (likelihood ratio test P < 0.01), although there was no significant difference between the various cohorts examined in the present study (however, the number of data points investigating the presence of fever in contacts of known COVID-19 cases, which is more likely to represent community transmission, were relatively low; see Fig. 3a). The percentage of people with malarial fever and how this varies with age are estimated from our malaria transmission dynamics model. Results of both models are then combined assuming that the prevalences of the two diseases are independent. The malaria model is also used to estimate the proportion of patent infections that are asymptomatic to determine the prevalence of asymptomatic malaria cases in COVID-19-infected individuals.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data used in this study are from publicly accessible sources accessed from the DHS (https://dhsprogram.com), PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) or Ovid MEDLINE (https://ovidsp.ovid.com). The results of the modeling work are available from the corresponding author for different regions and scenarios on reasonable request.

Code availability

Full details of the COVID-19 and malaria models, their code and parameterization are freely available at https://github.com/mrc-ide/squire and https://github.com/jamiegriffin/Malaria_simulation, respectively (accessed 22 April 2020). The malaria model was written in C++ code whereas the COVID-19 model was written in R using the ODIN package (https://github.com/mrc-ide/odin).

References

Massinga Loembé, M. et al. COVID-19 in Africa: the spread and response. Nat. Med. 26, 999–1003 (2020).

Brand, S. P. C. et al. Forecasting the scale of the COVID-19 epidemic in Kenya. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.09.20059865 (2020).

Thompson, H. A. et al. The projected impact of mitigation and suppression strategies on the COVID-19 epidemic in Senegal: a modelling study. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.03.20144949 (2020).

Walker, P. G. T. et al. The impact of COVID-19 and strategies for mitigation and suppression in low- and middle-income countries. Science 369, 413–422 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc0035

Bhatt, S. et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526, 207–211 (2015).

The Potential Impact of Health Service Disruptions on the Burden of Malaria: A Modelling Analysis for Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa 1–44 (WHO, 2020); https://www.who.int/publications-detail/the-potential-impact-of-health-service-disruptions-on-the-burden-of-malaria

Hogan, A. B. et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Global Health https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30288-6 (2020).

Global Malaria Programme: Tailoring Malaria Interventions in the COVID-19 Response (WHO, 2020); https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/tailoring-malaria-interventions-in-the-covid-19-response

Griffin, J. T. et al. Potential for reduction of burden and local elimination of malaria by reducing Plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 465–472 (2016).

Global Malaria Programme: Achieving and Maintaining Universal Coverage with Long-lasting Insecticidal Nets for Malaria Control Vol. 4 (WHO, 2017); http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/who_recommendation_coverage_llin/en

Hemingway, J. et al. Averting a malaria disaster: will insecticide resistance derail malaria control? Lancet 387, 1785–1788 (2016).

Diop, B. Z., Ngom, M., Pougué Biyong, C. & Pougué Biyong, J. N. The relatively young and rural population may limit the spread and severity of COVID-19 in Africa: a modelling study. BMJ Global Health 5, e002699 (2020).

Guidance on Temporary Malaria Control Measures in Ebola-affected Countries (WHO, 2014); https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/malaria-control-ebola-affected-countries/en

Dalrymple, U. et al. The contribution of non-malarial febrile illness co-infections to Plasmodium falciparum case counts in health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa. Malar. J. 18, 195 (2019).

Ferguson, N. M. et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team https://doi.org/10.25561/77482 (2020).

Verity, R. et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 669–677 (2020).

le Polain de Waroux, O. et al. Characteristics of human encounters and social mixing patterns relevant to infectious diseases spread by close contact: a survey in Southwest Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 172 (2018).

World Malaria Report 2019 (WHO, 2019); https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-malaria-report-2019

Murthy, S., Leligdowicz, A. & Adhikari, N. K. J. Intensive care unit capacity in low-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 10, e0116949 (2015).

Flaxman, S. et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7 (2020).

World Malaria Report 2017 (WHO, 2017); https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2017

Sherrard-Smith, E. et al. Systematic review of indoor residual spray efficacy and effectiveness against Plasmodium falciparum in Africa. Nat. Commun. 9, 4982 (2018).

Churcher, T. S., Lissenden, N., Griffin, J. T., Worrall, E. & Ranson, H. The impact of pyrethroid resistance on the efficacy and effectiveness of bednets for malaria control in Africa. eLife 5, e16090 (2016).

Walker, P. G. T., Griffin, J. T., Ferguson, N. M. & Ghani, A. C. Estimating the most efficient allocation of interventions to achieve reductions in Plasmodium falciparum malaria burden and transmission in Africa: a modelling study. Lancet Global Health 4, e474–e484 (2016).

Garske, T., Ferguson, N. M. & Ghani, A. C. Estimating air temperature and its influence on malaria transmission across Africa. PLoS ONE 8, e56487 (2013).

Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS Program, 2019); https://dhsprogram.com

Cairns, M. et al. Estimating the potential public health impact of seasonal malaria chemoprevention in African children. Nat. Commun. 3, 881 (2012).

Tangena, J.-A. A. et al. Indoor residual spraying for malaria control in sub-Saharan Africa 1997 to 2017: an adjusted retrospective analysis. Malar. J. 19, 150 (2020).

Cai, J. H. et al. [First case of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children in Shanghai]. Chinese J. Pediatr. 58, 86–87 (2020).

Jiehao, C. et al. A case series of children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection: clinical and epidemiological features. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa198 (2020).

Cai, Q. et al. COVID-19 in a designated infectious diseases hospital outside Hubei Province, China. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14309 (2020).

Bialek, S. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children—United States, February 12–April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 69, 422–426 (2020).

Chan, J. F.-W. et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet 395, 514–523 (2020).

Chang, D. et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China. JAMA 323, 1092 (2020).

Chen, D. et al. Assessment of hypokalemia and clinical characteristics in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wenzhou, China. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2011122 (2020).

Feng, C. et al. The first case of critically ill new coronavirus pneumonia in children in China. Chin. J. Pediatr. 58, 179–182 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 2620–2629 (2020).

Chen, N. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 395, 507–513 (2020).

Du, W. et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in children compared with adults in Shandong Province, China. Infection 48, 445–452 (2020).

Feng, K. et al. Analysis of CT features of 15 children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection. Chin. J. Pediatr. 58, E007 (2020).

Guan, W. et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1708–1720 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020).

Jiang, J. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infection in children: thoughts on the diagnostic criteria of suspected cases outside Hubei Province. Chin. Pediatr. Emerg. Med. 12, E003 (2020).

Kam, K. et al. A well infant with coronavirus disease 2019 with high viral load. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa201 (2020).

Kamali Aghdam, M., Jafari, N. & Eftekhari, K. Novel coronavirus in a 15-day-old neonate with clinical signs of sepsis, a case report. Infect. Dis. (Auckl.) 52, 427–429 (2020).

Li, B., Shen, J., Li, L. & Yu, C. Radiographic and clinical features of children with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia. Indian Pediatr. 57, 423–426 (2020).

Li, W., Cui, H., Li, K., Fang, Y. & Li, S. Chest computed tomography in children with COVID-19 respiratory infection. Pediatr. Radiol. 50, 796–799 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine 55, 102763 (2020).

Liu, W. et al. Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1370–1371 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Clinical features and progression of acute respiratory distress syndrome in coronavirus disease 2019. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.17.20024166 (2020).

Lu, X. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1663–1665 (2020).

Yao-Ling, M. A. et al. Clinical features of children with SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 115 cases. Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 22, 290–293 (2020).

Qiu, H. et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of 36 children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Zhejiang, China: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 689–696 (2020).

Phan, L. T. et al. Importation and human-to-human transmission of a novel coronavirus in vietnam. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 872–874 (2020).

Schwartz, D. A. & Graham, A. L. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) infecting pregnant women: lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections. Viruses 12, 194 (2020).

Shen, Q. et al. Novel coronavirus infection in children outside of Wuhan, China. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 55, 1424–1429 (2020).

Sinha, I. P. et al. COVID-19 infection in children. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 446–447 (2020).

Song, F. et al. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology 295, 210–217 (2020).

Su, L. et al. The different clinical characteristics of corona virus disease cases between children and their families in China—the character of children with COVID-19. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 707–713 (2020).

Sun, D. et al. Clinical features of severe pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan: a single center’s observational study. World J. Pediatr. 16, 251–259 (2020).

Tan, X. et al. Clinical features of children with SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 13 cases from Changsha, China. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 22, 294–298 (2020).

Tan, Y. et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of 10 children with coronavirus disease 2019 in Changsha, China. J. Clin. Virol. 127, 104353 (2020).

Tong, Z.-D. et al. Potential presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Zhejiang Province, China, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 1052–1054 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Clinical analysis of 31 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children from six provinces (autonomous region) of northern China. Chin. J. Pediatr. 58, 269–274 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323, 1061 (2020).

Wang, H., Li, Y., Wang, F., Du, H. & Lu, X. Rehospitalization of a recovered coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) child with positive nucleic acid detection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 39, e69–e70 (2020).

Wei, M. et al. Novel coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. JAMA 323, 1313–1314 (2020).

Xia, W. et al. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID‐19 infection: different points from adults. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 55, 1169–1174 (2020).

Xing, Y.-H. et al. Prolonged viral shedding in feces of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 53, 473–480 (2020).

Xu, Y. et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat. Med. 26, 502–505 (2020).

Yang, P., Liu, P., Li, D. & Zhao, D. Corona virus disease 2019, a growing threat to children? J. Infect. 80, 671–693 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 475–481 (2020).

Zeng, L. K. et al. First case of neonate infected with novel coronavirus pneumonia in China. Chin. J. Pediatr. 58, E009 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 75, 1730–1741 (2020).

Zhang, M. Q. et al. Clinical features of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in the early stage from a fever clinic in Beijing. Chin. J. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 43, E013 (2020).

Yuehua, Z. et al. 2019 novel coronavirus infection in a three-month-old baby. Chin. J. Pediatr. 58, 182–184 (2020).

Zheng, F. et al. Clinical characteristics of children with coronavirus disease 2019 in Hubei, China. Curr. Med. Sci. 40, 275–280 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Clinical features and chest CT findings of coronavirus disease 2019 in infants and young children. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi 22, 215–220 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the UK Medical Research Council under a concordat with the UK Department for International Development (no. MR/R015600/1 to M.B, L.O, P.W., A.G. and T.C), the Wellcome Trust (no. 200222/Z/15/Z to T.C.) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (to A.G.). We thank all those who facilitated collation of the data provided by the NMEP in Nigeria. The maps in the figures were prepared using GADM v.3.6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.G., P.G.T.W., O.O.O. and T.S.C. conceived the study. E.S.-S., A.B.H., A.H., O.J.W., C.W. P.W., H.C.S., A.C.G., P.G.T.W. and T.S.C. designed the models. P.W., F.A., A.B.M., P.U., I.M., N.O., J.N., M.D.K., J.D.C., R.V., B.L., M.C., B.R., M.B., L.K.W., J.A.L., S.B., E.S.K., L.O. and H.C.S. provided input parameters and analyses. E.S.-S., A.B.H. and A.H. processed the data. E.S.-S., A.B.H., A.H., A.C.G., P.G.T.W., O.O.O. and T.S.C. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results, contributed to writing and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Jennifer Sargent was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Projected deaths due to COVID-19 and malaria in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) over time for different COVID-19 scenarios.

The top row shows the COVID-19 epidemic and the number of people needing oxygen support per week for four different COVID-19 scenarios—an unmitigated epidemic (red), mitigation (blue), continued suppression (green), and suppression lift (purple). The thin dotted horizontal grey line indicates estimated healthcare capacity for a typical African country. The thick black horizontal line beneath each figure shows the period when COVID-19 mitigation or suppression activities are assumed in operation. The upper middle row indicates the assumed duration of interruption where COVID-19 interventions affect different malaria prevention activities (IRS = indoor residual spraying, LLINs = mass distribution of long-lasting insecticide treated nets, SMC = seasonal malaria chemoprevention) or case management of clinical cases with the level of this disruption presented in Table 2. The lower middle row shows the predicted deaths due to COVID-19 per week in each scenario. The bottom row shows predicted malaria deaths per week for each scenario (coloured lines) and for the counter-factual with no COVID-19 induced disruption (black lines). The top coloured lines indicate a scenario when all services are reduced or cease (Table 2, row 1) whereas the bottom dashed coloured lines show the most well-managed scenario (Table 2, row 3). Grey lines in all rows show other scenarios to allow direct comparison.

Extended Data Fig. 2

Maps showing the impact of COVID-19 based interruption of malaria control activities for the a, Unmitigated, b, Suppression and c, Suppression lift scenarios. As shown in Fig. 2a for the COVID-19 mitigated scenario, estimated additional deaths per million people when all malaria interventions are ceased (long-lasting insecticide treated net distribution campaigns, seasonal malaria chemoprevention, and clinical treatment of cases) relative to normal service in the absence of COVID-19 for each administrative region. The different periods of service disruption are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. Maps illustrate how overall impact depend on the timing and duration of the period of service interruption and how this overlaps with malaria transmission seasons in different regions of Africa and were made in GADM 3.6 (https://gadm.org/).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Univariate and multivariate sensitivity analyses of the effect of model parameters on the magnitude and duration of COVID-19 epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa.

a, Univariate sensitivity analysis showing the differences in the number of people needing supplemental oxygen, and the duration of the epidemic for four value of R0 (2–3.5) across the four COVID-19 intervention scenarios (using default parameters shown in Supplementary Table 11). Note that in the mitigation scenario a 6-month period of social distancing results in a rebound epidemic for R0 values < 3.0. In this plot the dotted lines show the same runs with 12 months of social distancing measures which prevents the rebound epidemic. b–e, Multivariate sensitivity analysis for the COVID-19 mitigation scenario using the range of parameters outlined in Supplementary Table 11. b, Epidemic trajectories for the 500 different simulations showing the variability in the shape of the epidemic. Runs are coloured according to the potential period that malaria services might be interrupted which are estimated from the different individual epidemic curves. This period of service disruption starts from when mitigation measures are initiated and continues until the time healthcare capacity is no-longer over-burdened. c, the relationship between the assumed level of R0 and level of social distancing during the mitigation period (% reduction in the contact rate) and the period of service interruption. Each point represents a single realisation of the 500 runs. Values where healthcare was still over capacity a year after the arrival of the epidemic are grouped at a year of service interruption. d, A histogram showing period of potential service interruption for the 500 runs. Bar colour indicates the numbers of deaths due to COVID-19 for the different simulations and show a high number of COVID-19 deaths can occur with a short period of interruption (for example, from a high R0) or from an epidemic that causes a longer period of disruption (for example, a low R0 and a rebound epidemic once mitigation measures are relaxed). The period of service disruption used in the default mitigation scenario in the main paper analysis is shown with a vertical dashed line in panel (e). Histogram showing the distribution of the number of COVID-19 deaths from the 500 runs of the multivariate sensitivity analysis. This distribution of was used to generate 95% uncertainty interval estimates for COVID-19 mitigation scenario deaths in Table 1. Histogram colours show the R0 values used in that simulation.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Maps showing how the impact malaria mitigation strategies are predicted to vary across sub-Saharan Africa.

a, Expansion of existing seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) in regions where it occurred in the Sahel where it was conducted in 2019. Colours denote additional lives saved by expanding the age of those eligible from under 5 years to under 15 years. b, The predicted impact of mass drug administration (MDA) using a drug with a prophylactic profile of amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for regions where SMC is not currently conducted. Both figures show scenarios where existing LLIN campaigns were maintained but routine treatment of clinical cases paused during the mitigated COVID-19 scenario.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Sub-national impact of how interruption of malaria services due to a mitigation COVID-19 scenario will influence the numbers of malaria deaths in different states of Nigeria.

The colour indicates the additional deaths predicted due to service interruption relative to normal service in the absence of COVID-19 for each state. Here the top row corresponds to the scenarios where net distribution is maintained and MDA is expanded, as per Supplementary Table 10, and the bottom row corresponds to scenarios where net distribution is maintained and seasonal malaria chemoprevention is expanded as per Supplementary Table 8. Grey areas denote states where this control intervention was not considered. Expansion of SMC was only evaluated in regions which undertook SMC in 2019 (bottom row) whilst MDA was considered in all other states (top row). All simulations assume that sufficient drugs are available. Maps were made in GADM 3.6 (https://gadm.org/).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Nigeria-specific data inputs for the malaria model estimations.

a, Malaria prevalence by microscopy in children 6–59 months of age. b, Percentage of children sleeping under an insecticidal net the previous night. c, Estimates of seasonal malaria chemoprevention coverage calculated by dividing the number of doses administered by the proportion of the target age group. d, Estimates of the percentage of child malaria cases receiving artemisinin combination therapy (ACT). Figures (a), (b) and (d) were estimated from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data. All estimates were at the state level other than (d) which was presented at the regional level. Maps were made in GADM 3.6 (https://gadm.org/).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Multivariate uncertainty analysis for the malaria transmission model.

The true model uncertainty was quantified by calculating the additional clinical malaria cases, malaria deaths, and years of life lost due to malaria, using an additional 20 draws from the joint posterior distribution of the fitted model parameters. These simulations were performed for all 37 administrative 1 units in Nigeria, and 40 other units across four countries—Zambia (all provinces included), Mozambique, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Burkina Faso—and for each COVID-19 and malaria scenario. We used the outcomes for the Nigeria administrative units to calculate the coefficient of variation (CoV) and tested the application of a Normal approximation to compare the uncertainty intervals (UI) for the other countries. a, Shows the 95% UI for each of the four countries estimated from the different model runs (pink and purple error bars) with values estimated from the Normal approximation and fitted CoV values (red bars). Results indicate that the uncertainty generated using both methods was broadly similar. b, Illustration of how malaria parameter uncertainty influences estimates of the additional weekly deaths due to malaria in Nigeria over the year May 2020–April 2021 for each of the four COVID-19 scenarios. Two different levels of malaria service interruption are considered for each scenario, the first where LLINs and SMC are ceased and case management is reduced by 50% (pink line, Supplementary Table 1 row 1), and the second when only case management is reduced by 50% (purple line, Supplementary Table 1, row 3). The solid dark lines represent best guess model predictions for the additional malaria deaths (difference between the levels of malaria service interruption and no COVID-19 induced disruption) whilst the shaded regions represent the 95% UIs generated by varying the input parameters within plausible ranges.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables 1–13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sherrard-Smith, E., Hogan, A.B., Hamlet, A. et al. The potential public health consequences of COVID-19 on malaria in Africa. Nat Med 26, 1411–1416 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1025-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1025-y

This article is cited by

-

Rapid classification of epidemiologically relevant age categories of the malaria vector, Anopheles funestus

Parasites & Vectors (2024)

-

Novel Plasmodium falciparum k13 gene polymorphisms from Kisii County, Kenya during an era of artemisinin-based combination therapy deployment

Malaria Journal (2023)

-

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on general health and malaria control in Ghana: a qualitative study with mothers and health care professionals

Malaria Journal (2023)

-

Outcomes of childhood severe malaria: a comparative of study pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods

BMC Pediatrics (2023)

-

Impact of methods of estimating baseline Serum Creatinine (bSCr) on the incidence and outcomes of acute kidney injury in childhood severe malaria

Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette (2023)