Abstract

Young-onset Parkinson’s disease (YOPD), defined by onset at <50 years, accounts for approximately 10% of all Parkinson’s disease cases and, while some cases are associated with known genetic mutations, most are not. Here induced pluripotent stem cells were generated from control individuals and from patients with YOPD with no known mutations. Following differentiation into cultures containing dopamine neurons, induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with YOPD showed increased accumulation of soluble α-synuclein protein and phosphorylated protein kinase Cα, as well as reduced abundance of lysosomal membrane proteins such as LAMP1. Testing activators of lysosomal function showed that specific phorbol esters, such as PEP005, reduced α-synuclein and phosphorylated protein kinase Cα levels while increasing LAMP1 abundance. Interestingly, the reduction in α-synuclein occurred through proteasomal degradation. PEP005 delivery to mouse striatum also decreased α-synuclein production in vivo. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived dopaminergic cultures reveal a signature in patients with YOPD who have no known Parkinson’s disease-related mutations, suggesting that there might be other genetic contributions to this disorder. This signature was normalized by specific phorbol esters, making them promising therapeutic candidates.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All requests for raw and analyzed data and materials are promptly reviewed by the Cedars-Sinai Board of Governor’s Regenerative Medicine Institute to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Patient-related data not included in the paper may be subject to patient confidentiality. Any data and materials that can be shared will be released via a material transfer agreement. All transcriptomic data from this study are available in the GEO repository under GSE120746. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium with the dataset identifier PXD011326.

References

Puschmann, A. Monogenic Parkinson’s disease and Parkinsonism: clinical phenotypes and frequencies of known mutations. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 19, 407–415 (2013).

Kalia, L. V. & Lang, A. E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 386, 896–912 (2015).

Spillantini, M. G. et al. α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388, 839–840 (1997).

Lashuel, H. A., Overk, C. R., Oueslati, A. & Masliah, E. The many faces of α-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 38–48 (2013).

Singleton, A. B. et al. α-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science 302, 841–841 (2003).

Shi, Y., Inoue, H., Wu, J. C. & Yamanaka, S. Induced pluripotent stem cell technology: a decade of progress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 16, 115–130 (2017).

Studer, L., Vera, E. & Cornacchia, D. Programming and reprogramming cellular age in the era of induced pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 16, 591–600 (2015).

Kim, K. et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 467, 285–290 (2010).

Woodard, ChrisM. et al. iPSC-derived dopamine neurons reveal differences between monozygotic twins discordant for Parkinson’s disease. Cell Rep. 9, 1173–1182 (2014).

Soldner, F. et al. Parkinson’s disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell 136, 964–977 (2009).

Byers, B. et al. SNCA triplication Parkinson’s patient’s iPSC-derived DA neurons accumulate α-synuclein and are susceptible to oxidative stress. PLoS One 6, e26159 (2011).

Devine, M. J. et al. Parkinson’s disease induced pluripotent stem cells with triplication of the α-synuclein locus. Nat. Commun. 2, 440 (2011).

Oliveira, L. M. et al. Elevated α-synuclein caused by SNCA gene triplication impairs neuronal differentiation and maturation in Parkinson’s patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1994 (2015).

Schondorf, D. C. et al. iPSC-derived neurons from GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease patients show autophagic defects and impaired calcium homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 5, 4028 (2014).

Sanchez-Danes, A. et al. Disease-specific phenotypes in dopamine neurons from human iPS-based models of genetic and sporadic Parkinson’s disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 4, 380–395 (2012).

Sanders, L. H. et al. LRRK2 mutations cause mitochondrial DNA damage in iPSC-derived neural cells from Parkinson’s disease patients: reversal by gene correction. Neurobiol. Dis. 62, 381–386 (2014).

Schwab, A. J. & Ebert, A. D. Neurite aggregation and calcium dysfunction in iPSC-derived sensory neurons with Parkinson’s disease-related LRRK2 G2019S mutation. Stem Cell Rep. 5, 1039–1052 (2015).

Schrag, A. & Schott, J. M. Epidemiological, clinical, and genetic characteristics of early-onset Parkinsonism. Lancet Neurol. 5, 355–363 (2006).

Rizek, P., Kumar, N. & Jog, M. S. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease. CMAJ 188, 1157–1165 (2016).

Pagano, G., Ferrara, N., Brooks, D. J. & Pavese, N. Age at onset and Parkinson disease phenotype. Neurology 86, 1400–1407 (2016).

Alcalay, R. N. et al. Frequency of known mutations in early-onset parkinson disease: implication for genetic counseling: the consortium on risk for early-onset Parkinson disease study. Arch. Neurol. 67, 1116–1122 (2010).

Ebert, A. D. et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature 457, 277–280 (2009).

Nalls, M. A. et al. NeuroX, a fast and efficient genotyping platform for investigation of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 1605 e1607–1605 e1612 (2015).

Nalls, M. A. et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 18, 1091–1102 (2019).

Kriks, S. et al. Dopamine neurons derived from human ES cells efficiently engraft in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature 480, 547–551 (2011).

Kikuchi, T. et al. Human iPS cell-derived dopaminergic neurons function in a primate Parkinson’s disease model. Nature 548, 592–596 (2017).

Reyes, S. et al. GIRK2 expression in dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. J. Comp. Neurol. 520, 2591–2607 (2012).

Bennett, M. C. et al. Degradation of α-synuclein by proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33855–33858 (1999).

Webb, J. L., Ravikumar, B., Atkins, J., Skepper, J. N. & Rubinsztein, D. C. α-Synuclein is degraded by both autophagy and the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25009–25013 (2003).

Mak, S. K., McCormack, A. L., Manning-Bog, A. B., Cuervo, A. M. & Di Monte, D. A. Lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13621–13629 (2010).

Xilouri, M., Brekk, O. R. & Stefanis, L. α-Synuclein and protein degradation systems: a reciprocal relationship. Mol. Neurobiol. 47, 537–551 (2013).

Mazzulli, J. R., Zunke, F., Isacson, O., Studer, L. & Krainc, D. α-Synuclein-induced lysosomal dysfunction occurs through disruptions in protein trafficking in human midbrain synucleinopathy models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1931–1936 (2016).

Murphy, K. E. et al. Reduced glucocerebrosidase is associated with increased α-synuclein in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Brain 137, 834–848 (2014).

Burbulla, L. F. et al. Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Science 357, 1255–1261 (2017).

Decressac, M. et al. TFEB-mediated autophagy rescues midbrain dopamine neurons from α-synuclein toxicity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E1817–E1826 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Protein kinase C controls lysosome biogenesis independently of mTORC1. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 1065–1077 (2016).

Sarkar, S. et al. Small molecules enhance autophagy and reduce toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 331–338 (2007).

Sarkar, S., Davies, J. E., Huang, Z., Tunnacliffe, A. & Rubinsztein, D. C. Trehalose, a novel mTOR-independent autophagy enhancer, accelerates the clearance of mutant huntingtin and α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5641–5652 (2007).

Li, Y. H. et al. α-Synuclein functions as a negative regulator for expression of tyrosine hydroxylase. Acta Neurol. Belg. 111, 130–135 (2011).

Deary, I. J. et al. The Lothian Birth Cohort 1936: a study to examine influences on cognitive ageing from age 11 to age 70 and beyond. BMC Geriatr. 7, 28 (2007).

Asati, V., Mahapatra, D. K. & Bharti, S. K. PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways inhibitors as anticancer agents: structural and pharmacological perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 109, 314–341 (2016).

Roczniak-Ferguson, A. et al. The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Sci. Signal. 5, ra42 (2012).

Schneider, B. L. et al. Over-expression of α-synuclein in human neural progenitors leads to specific changes in fate and differentiation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 651–666 (2007).

Chang, D. et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat. Genet. 49, 1511–1516 (2017).

Wong, Y. C. & Krainc, D. α-Synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 23, 1–13 (2017).

Dehay, B. et al. Lysosomal impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 28, 725–732 (2013).

Imaizumi, Y. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction associated with increased oxidative stress and α-synuclein accumulation in PARK2 iPSC-derived neurons and postmortem brain tissue. Mol. Brain 5, 35 (2012).

Suzuki, S. et al. Efficient induction of dopaminergic neuron differentiation from induced pluripotent stem cells reveals impaired mitophagy in PARK2 neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 483, 88–93 (2017).

Ishikawa, K. I., Yamaguchi, A., Okano, H. & Akamatsu, W. Assessment of mitophagy in iPS cell-derived neurons. Methods Mol. Biol. 1759, 59–67 (2018).

Ridge, P. G. & Kauwe, J. S. K. Mitochondria and Alzheimer’s disease: the role of mitochondrial genetic variation. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 6, 1–10 (2018).

Fujimori, K. et al. Modeling sporadic ALS in iPSC-derived motor neurons identifies a potential therapeutic agent. Nat. Med. 24, 1579–1589 (2018).

Yu, S. et al. Inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in α-synuclein-transfected dopaminergic neuronal cells. Neurosci. Lett. 367, 34–39 (2004).

Halskau, O. Jr. et al. Three-way interaction between 14-3-3 proteins, the N-terminal region of tyrosine hydroxylase, and negatively charged membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32758–32769 (2009).

Ostrerova, N. et al. α-Synuclein shares physical and functional homology with 14-3-3 proteins. J. Neurosci. 19, 5782–5791 (1999).

Xu, Y. et al. YWHA/14-3-3 proteins recognize phosphorylated TFEB by a noncanonical mode for controlling TFEB cytoplasmic localization. Autophagy 15, 1017–1030 (2019).

Hampson, P. et al. Kinetics of ERK1/2 activation determine sensitivity of acute myeloid leukaemia cells to the induction of apoptosis by the novel small molecule ingenol-3-angelate (PEP005). Apoptosis 15, 946–955 (2010).

Jiang, G. et al. Synergistic reactivation of latent HIV expression by ingenol-3-angelate, PEP005, targeted NF-kB signaling in combination with JQ1-induced p-TEFb activation. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005066 (2015).

Garg, R. et al. Protein kinase C and cancer: what we know and what we do not. Oncogene 33, 5225–5237 (2014).

Scheuer, T. Regulation of sodium channel activity by phosphorylation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 160–165 (2011).

Chesselet, M. F. et al. A progressive mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: the Thy1-aSyn (“Line 61”) mice. Neurotherapeutics 9, 297–314 (2012).

Barrett, R. et al. Reliable generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Stem Cell Transl. Med. 3, 1429–1434 (2014).

Mazzulli, J. R. et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell 146, 37–52 (2011).

Marshall, J. et al. Demonstration of feasibility of in vivo gene therapy for gaucher disease using a chemically induced mouse model. Mol. Ther. 6, 179–189 (2002).

Ho, R. et al. ALS disrupts spinal motor neuron maturation and aging pathways within gene co-expression networks. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1256–1267 (2016).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 323 (2011).

Schubert, O. T. et al. Building high-quality assay libraries for targeted analysis of SWATH MS data. Nat. Protoc. 10, 426–441 (2015).

Teo, G. et al. mapDIA: preprocessing and statistical analysis of quantitative proteomics data from data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry. J. Proteom. 129, 108–120 (2015).

Parker, S. J., Venkatraman, V. & Van Eyk, J. E. Effect of peptide assay library size and composition in targeted data-independent acquisition-MS analyses. Proteomics 16, 2221–2237 (2016).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene-set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Zhang, G., Kazanietz, M. G., Blumberg, P. M. & Hurley, J. H. Crystal structure of the cys2 activator-binding domain of protein kinase C in complex with phorbol ester. Cell 81, 917–924 (1995).

Kim, D. E., Chivian, D. & Baker, D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W526–W531 (2004).

Morin, A. et al. Collaboration gets the most out of software. eLife 2, e01456 (2013).

Holm, L., Kaariainen, S., Wilton, C. & Plewczynski, D. Using Dali for structural comparison of proteins. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 5, 5 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Svendsen for critical input and editing of the manuscript and T. Pierson for consultation on protein degradation and additional editing of the manuscript. We also thank A. Singleton and D. Hernandez for NeuroX analysis and WGS of patient samples, R. Holewinski for assistance with proteomic analysis and sample acquisition, V. Mattis and H. Park for assisting with striatal dissections, D. Torolina for sectioning and staining of mouse brains and G. Lawless for assistance with ELISA assays. We also thank the Cedars-Sinai Proteomics and Metabolomics Core. The majority of this work was supported by the Joseph Drown Foundation (C.N.S.) and the Board of Governors Regenerative Medicine Institute (C.N.S.) and a National Institutes of Health grant, 5UG3NS105703-02 (C.N.S.). Support for the clinical sample collection and patient information came from the Widjaja Family Foundation (M.T.). Support for the proteomics analysis was from the Advanced Clinical Biosystems Institute (J.E.V.E.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H.L., S.S., N.Y. and C.N.S. designed experiments. A.H.L., S.S., N.Y., V.J.D., V.J.G. and A.N.F. performed experiments. A.H.L., S.S. and C.N.S. wrote the manuscript. S.S. and R.H. performed transcriptomic analysis. P.A. performed all animal work and K.M.R. processed brain tissue. S.S., A.H.L., D.W. and M.G.B. generated YOPD iPSC lines. R.M. performed in silico modeling. M.R.J. performed WGS analysis. Z.S. and N.T.M. performed dopamine release experiments. J.E.V.E. supervised the proteomic data analysis. M.T. provided patient samples and clinical data, and helped supervise the project. C.N.S. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

An intellectual protection patent is pending for diagnostic and drug screening for molecular signatures of early-onset sporadic Parkinson’s disease.

Additional information

Peer review information Brett Benedetti and Kate Gao were the primary editors on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Generation of YOPD iPSCs.

(a) SSEA4 (green) and OCT-4 immunostaining in undifferentiated iPSCs from YOPD patients. (b) Normal karyotypes from YOPD patient iPSCs, 20 metaphase spreads were analyzed for each line.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Additional characterization of mDA cultures.

(a) Expression of dopaminergic neuron genes in day 30 mDA cultures from 6 iPSC lines. 3 biological replicates per line were averaged. Data are normalized to average expression in control lines and presented as 3 CTR vs 3 PD lines. No significant differences were detected using multiple t-tests with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. (b) HPLC detection of total dopamine in d30 mDA culture lysates. n=9 CTR n=9 PD not significant p=0.29 two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction. (c) HPLC detection of released dopamine in aCSF following a 15 min incubation at 37oC. n=9 CTR n=9 not significant p=0.14 two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction. (d) MEA recording of spontaneous activity from 02iCTR mDA neurons at day 21 of differentiation. (e) MEA recordings of control and YOPD mDA neurons at d30 of differentiation. (f) Average sorted spikes per neuron at d30. Points represent an average of 4 independent wells, n=6 CTR n=6 PD colors indicate iPSC lines. Bar graphs represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Whole-cell patch clamp measurements from control and YOPD mDA cultures.

(a) Capacitance is similar between control and YOPD. (b) No difference in resting membrane potential (RMP) is observed. (c) Voltage-gated sodium current density is decreased in YOPD compared to control. No difference is observed in either the (d) inwards rectifying potassium current density, or (e) delayed rectifier potassium current density. * denotes significance p = 0.018 two tailed t-test with Welch’s correction. Bar graphs represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Western blots of soluble and insoluble lysate fractions.

Western blot of D30 mDA cultures under non-denaturing conditions for α-synuclein and loading control of β-actin. Fractionation experiment was conducted once in 5 independent iPSC lines.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Western blots of YOPD markers in undifferentiated iPSCs.

(a) Western blot of p-PKCα and α-Syn in undifferentiated iPSCs and (b) relative quantification of α-Syn levels (n=4 CTR n=5 PD p=0.87 two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction); no quantification of p-PKCα was possible in the iPSCs as no bands were detected. Bar graphs represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Paired transcriptomic and proteomic analysis.

Pearson correlation plots of (a) transcriptomic and (b) proteomic data. (c) PCA plot of all detected proteins. (d) PCA plot of matching RNA-Seq transcripts. (e) PCA plot of matching proteins. (f) PCA plots of filtered data with 190iPD line omitted. (g) Matched GSEA terms conducted on 190iPD omitted data set n=9 CTR n=6 PD term significance determined by FDR <0.1.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Testing of additional Proteosomal inhibitors.

(a) Western blot of D30 mDA cultures in the presence of indicated proteasomal inhibitors. Quantification of blots from multiple differentiations (n=4 CTR, n=4 PD) with each point representing a band intensity from a separate differentiation. (b) P53 one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test (F 17.53 DF 20 p=0.0005 CTR Lac p=0.0003 CTR Epox p=0.0009 PD Lac p=0.001 PD Epox). (c) α-Syn one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test (F 1.6 DF 20 p=0.0.21). Bar graphs represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Additional characterization of PEP005 treatment.

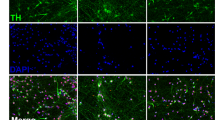

(a) Immunocytochemistry showing TH and α-synuclein (α-Syn) in 200iPD d30 mDA cultures with and without PEP005 treatment. Images are representative of 2 additional lines tested. (b) Day 30 mDA neurons treated with PEP005 from multiple YOPD and control lines. (c) Quantification of LC3I/II and α-Syn band intensities relative to untreated cells from the same line. (d) Time-course of PEP005 treatment in YOPD and control mDA neurons. (e) Quantification of α-Syn, p-PKCα, LAMP1, and TH band intensities in YOPD and control mDA neurons in timecourse study. qPCR from paired samples (n=3 wells 02iCTR n=3 wells 190iPD) over PEP005 time-course showing (f) SNCA and (g) TH expression. Bar graphs represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.).

Extended Data Fig. 9 mDA differentiation across multiple lines and clones.

(a) Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) production by western blot across 8 control and 12 YOPD patients. TH levels were first normalized to β-actin, then to compare across blots the levels were normalized to the average signal (TH/ β-actin) of each gel. (b) Western blots of TH and α-synuclein (α-Syn) levels in day 30 mDA cultures across 3 unique clonal lines from ED044iCTR and from 192iPD. (c) Quantification of band intensities for TH and α-Syn normalized to β-actin. Bands represent independent biological replicates from 3 separate wells differentiated in the same experiment. *indicates p=0.0002 via one-way ANOVA (F 51.42, DF 8) with Tukey multiple comparisons test compared to other clones of the same line. Bar graphs represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Dose-response and in silico analysis of PEP005 and related molecules.

(a) Structures of Phorbol esters similar to PEP005 tested in mDA cultures. (b) Western blots of α-synuclein (α-Syn) and p-PKCα in response to varying PEP005 doses. (c) Western blots of α-Syn and p-PKCα in response to varying Prostratin (PRO) doses in both YOPD and control mDA cultures. Dose ranging studies were repeated twice. (d) Predictive modeling of PEP005 binding sites on PKCα and similar affinity sites on additional proteins. (e) Three dimensional model of PEP005 binding sites on PKCα, PKCδ, and Ras overlaid to show similarity.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplemental Tables 1–5 and example flow cytometry gating.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Unprocessed western blots.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laperle, A.H., Sances, S., Yucer, N. et al. iPSC modeling of young-onset Parkinson’s disease reveals a molecular signature of disease and novel therapeutic candidates. Nat Med 26, 289–299 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0739-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0739-1

This article is cited by

-

A naturally occurring variant of SHLP2 is a protective factor in Parkinson’s disease

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

CRISPR/Cas9 assisted stem cell therapy in Parkinson's disease

Biomaterials Research (2023)

-

Prosaposin maintains lipid homeostasis in dopamine neurons and counteracts experimental parkinsonism in rodents

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Prediction of mechanistic subtypes of Parkinson’s using patient-derived stem cell models

Nature Machine Intelligence (2023)

-

Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Dopaminergic Neurons for Studying Developmental Neurotoxicity

Stem Cell Reviews and Reports (2023)