Abstract

Studies in experimental systems have identified a multitude of mutational mechanisms including DNA replication infidelity and DNA damage followed by inefficient repair or replicative bypass. However, the relative contributions of these mechanisms to human germline mutation remain unknown. Here, we show that error-prone damage bypass on the lagging strand plays a major role in human mutagenesis. Transcription-coupled DNA repair removes lesions on the transcribed strand; lesions on the non-transcribed strand are preferentially converted into mutations. In human polymorphism we detect a striking similarity between mutation types predominant on the non-transcribed strand and on the strand lagging during replication. Moreover, damage-induced mutations in cancers accumulate asymmetrically with respect to the direction of replication, suggesting that DNA lesions are resolved asymmetrically. We experimentally demonstrate that replication delay greatly attenuates the mutagenic effect of ultraviolet irradiation, confirming that replication converts DNA damage into mutations. We estimate that at least 10% of human mutations arise due to DNA damage.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Experimental data generated in this study have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under accession SRP151915.

References

Lujan, S. A. et al. Heterogeneous polymerase fidelity and mismatch repair bias genome variation and composition. Genome Res. 24, 1751–1764 (2014).

Boiteux, S. & Jinks-Robertson, S. DNA repair mechanisms and the bypass of DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 193, 1025–1064 (2013).

Cohen, I. S. et al. DNA lesion identity drives choice of damage tolerance pathway in murine cell chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1637–1645 (2015).

Baker, A. et al. Replication fork polarity gradients revealed by megabase-sized U-shaped replication timing domains in human cell lines. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002443 (2012).

Chen, C.-L. et al. Replication-associated mutational asymmetry in the human genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2327–2337 (2011).

Polak, P. & Arndt, P. F. Transcription induces strand-specific mutations at the 5′ end of human genes. Genome Res. 18, 1216–1223 (2008).

Seplyarskiy, V. B., Andrianova, M. A. & Bazykin, G. A. APOBEC3A/B-induced mutagenesis is responsible for 20% of heritable mutations in the TpCpW context. Genome Res. 27, 175–184 (2017).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421 (2013).

Harland, C. et al. Frequency of mosaicism points towards mutation-prone early cleavage cell divisions. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/079863 (2016).

Lindsay, S. J., Rahbari, R., Kaplanis, J., Keane, T. & Hurles, M. Striking differences in patterns of germline mutation between mice and humans. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/082297 (2016).

Ju, Y. S. et al. Somatic mutations reveal asymmetric cellular dynamics in the early human embryo. Nature 543, 714–718 (2017).

Helleday, T., Eshtad, S. & Nik-Zainal, S. Mechanisms underlying mutational signatures in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 585–598 (2014).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Clock-like mutational processes in human somatic cells. Nat. Genet. 47, 1402–1407 (2015).

Podolskiy, D. I., Lobanov, A. V., Kryukov, G. V. & Gladyshev, V. N. Analysis of cancer genomes reveals basic features of human aging and its role in cancer development. Nat. Commun. 7, 12157 (2016).

Kong, A. et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature 488, 471–475 (2012).

Francioli, L. C. et al. Genome-wide patterns and properties of de novo mutations in humans. Nat. Genet. 47, 822–826 (2015).

Wong, W. S. W. et al. New observations on maternal age effect on germline de novo mutations. Nat. Commun. 7, 10486 (2016).

Moorjani, P., Gao, Z. & Przeworski, M. Human germline mutation and the erratic evolutionary clock. PLoS Biol. 14, e2000744 (2016).

Tomasetti, C., Li, L. & Vogelstein, B. Stem cell divisions, somatic mutations, cancer etiology, and cancer prevention. Science 355, 1330–1334 (2017).

Gao, Z., Wyman, M. J., Sella, G. & Przeworski, M. Interpreting the dependence of mutation rates on age and time. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002355 (2016).

Fousteri, M. & Mullenders, L. H. F. Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells: molecular mechanisms and biological effects. Cell Res. 18, 73–84 (2008).

Marteijn, J. A., Lans, H., Vermeulen, W. & Hoeijmakers, J. H. J. Understanding nucleotide excision repair and its roles in cancer and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 465–481 (2014).

Yeeles, J. T. P., Poli, J., Marians, K. J. & Pasero, P. Rescuing stalled or damaged replication forks. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a012815 (2013).

Roberts, S. A. & Gordenin, D. A. Hypermutation in human cancer genomes: footprints and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 786–800 (2014).

Supek, F. & Lehner, B. Clustered mutation signatures reveal that error-prone DNA repair targets mutations to active genes. Cell 170, 534–547 (2017).

Hedglin, M. & Benkovic, S. J. Eukaryotic translesion DNA synthesis on the leading and lagging strands: unique detours around the same obstacle. Chem. Rev. 117, 7857–7877 (2017).

Shen, J. C., Rideout, W. M. & Jones, P. A. The rate of hydrolytic deamination of 5-methylcytosine in double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 972–976 (1994).

Lek, M. et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536, 285–291 (2016).

Letouzé, E. et al. Mutational signatures reveal the dynamic interplay of risk factors and cellular processes during liver tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 8, 1315 (2017).

Zheng, C. L. et al. Transcription restores DNA repair to heterochromatin, determining regional mutation rates in cancer genomes. Cell Rep. 9, 1228–1234 (2014).

Adar, S., Hu, J., Lieb, J. D. & Sancar, A. Genome-wide kinetics of DNA excision repair in relation to chromatin state and mutagenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E2124–E2133 (2016).

Hu, J., Adebali, O., Adar, S. & Sancar, A. Dynamic maps of UV damage formation and repair for the human genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6758–6763 (2017).

Haradhvala, N. J. et al. Mutational strand asymmetries in cancer genomes reveal mechanisms of DNA damage and repair. Cell 164, 538–549 (2016).

Andrianova, M. A., Bazykin, G. A., Nikolaev, S. I. & Seplyarskiy, V. B. Human mismatch repair system balances mutation rates between strands by removing more mismatches from the lagging strand. Genome Res. 27, 1336–1343 (2017).

Morganella, S. et al. The topography of mutational processes in breast cancer genomes. Nat. Commun. 7, 11383 (2016).

Lujan, S. A. et al. Mismatch repair balances leading and lagging strand DNA replication fidelity. PLoS Genet. 8, e1003016 (2012).

Seplyarskiy, V. B. et al. APOBEC-induced mutations in human cancers are strongly enriched on the lagging DNA strand during replication. Genome Res. 26, 174–182 (2016).

Hoopes, J. I. et al. APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B preferentially deaminate the lagging strand template during DNA replication. Cell Rep. 14, 1273–1282 (2016).

Tomkova, M., Tomek, J., Kriaucionis, S. & Schuster-Boeckler, B. Widespread impact of DNA replication on mutational mechanisms in cancer. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/111302 (2017).

Sanz, L. A. et al. Prevalent, dynamic, and conserved R-loop structures associate with specific epigenomic signatures in mammals. Mol. Cell 63, 167–178 (2016).

Skourti-Stathaki, K. & Proudfoot, N. J. A double-edged sword: R loops as threats to genome integrity and powerful regulators of gene expression. Genes Dev. 28, 1384–1396 (2014).

Roberts, S. A. et al. Clustered mutations in yeast and in human cancers can arise from damaged long single-strand DNA regions. Mol. Cell 46, 424–435 (2012).

Burns, M. B. et al. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature 494, 366–370 (2013).

Quah, S.-K., von Borstel, R. C. & Hastings, P. J. The origin of spontaneous mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 96, 819–839 (1980).

Lawrence, C. W. & Maher, V. M. Mutagenesis in eukaryotes dependent on DNA polymerase ζ and Rev1p. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 356, 41–46 (2001).

Goldmann, J. M. et al. Parent-of-origin-specific signatures of de novo mutations. Nat. Genet. 48, 935–939 (2016).

Campbell, P. J. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/162784 (2017).

Scarpa, A. et al. Whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nature 543, 65–71 (2017).

The GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 348, 648–660 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Mirkin, D. Gordenin, C. Cassa and D. Weghorn for useful comments on the manuscript; L. Sanz and F. Chédin for help with R-loop data; and B. Boulerice for proofreading. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R35GM127131, R01MH101244 and U01HG009088; N.A. was supported by the Russian Science Foundation grant 16–15–10273, S.I.N. was supported by grant Foundation ARC 2017, Foundation Gustave Roussy and Swiss Cancer League KFC-3985-08-2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.B.S., G.A.B. and S.R.S. designed the study. V.B.S. performed the data analyses. V.B.S., E.E.A., N.A. and I.A. designed and performed experiments. M.A.A. performed data preprocessing and helped with results presentation. S.I.N. retrieved genomic data for squamous cell carcinoma. V.B.S. and S.R.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Integrated supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1 Concordance of R-asymmetries across different contexts between SNPs and de novo mutations.

The sparsity of currently available data on de novo mutations forces us to rely on the human polymorphism data as a proxy. R-asymmetry was calculated for six mutation types and one adjacent nucleotide (5′ in the left panel and 3′ in the right panel). We used one adjacent nucleotide rather than two because of insufficient data. CpG>TpG mutations were excluded; in the left panel, CpG>GpG and CpG>ApG mutations were also excluded because of the low numbers of de novo mutations of these types. De novo mutations were obtained from Francioli et al. and Wong et al. The P values for the correlations are 1.4 × 10–3 for the left panel and 3.3 × 10–4 for the right panel.

Supplementary Figure 2 R-asymmetry and T-asymmetry patterns in human polymorphism for pentanucleotide contexts.

Relationship between R-asymmetry and T-asymmetry for pentanucleotide contexts; all contexts containing CpG sites are excluded.

Supplementary Figure 3 T-asymmetry and R-asymmetry are correlated in tumor samples (each dot represents one tumor).

Relationship between R-asymmetry and T-asymmetry for tumor samples; only damage-induced mutations are considered (C>T for melanoma, G>T for LUAD and LUSC, and A>G for liver cancer).

Supplementary Figure 4 Lagging-strand bias is absent among G>T mutations in MUTYH-deficient cancer samples.

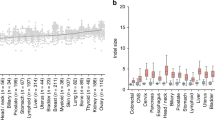

Error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals, calculated as the ratio of two binomial proportions based on likelihood scores (riskscoreci() function in R).

Supplementary Figure 5 Effect of XPC status on the level of R-asymmetry.

R-asymmetry for skin cancers. Bars corresponding to patients with xeroderma pigmentosum due to loss-of-function mutation in the XPC gene are colored red; bars corresponding to patients with intact XPC are colored turquoise. The P values is for two-sided Mann–Whitney U test.

Supplementary Figure 6 T-asymmetry of UV-induced damage.

T-asymmetry of repaired CPD damage (left) and remaining CPD damage (right) as a function of time since UV irradiation.

Supplementary Figure 7 CpG>TpG mutations are biased toward high values of R-asymmetry, and dependence of R-asymmetry on methylation.

a, Relationship between R-asymmetry and T-asymmetry in the human germ line shows that CpG>TpG mutations (highlighted by red circles) have higher values of T-asymmetry as compared to the expectations based on the values of T-asymmetry. b, CpG>TpG mutations within CpG islands are shown in gray; CpG>TpG mutations in CpG islands are shown in black. The propensity of DNA regions to be replicated as a lagging or a leading strand is shown on the x axis, and log R-asymmetry is shown on the y axis.

Supplementary Figure 8

T-asymmetry is not elevated in regions prone to R-loops as compared with flanking regions within the same transcript.

Supplementary Figure 9 XPC deficiency is associated with the prevalence of TCT>T mutations.

Fraction of C>T mutations in all trinucleotide contexts among all mutations. SCC, squamous carcinoma.

Supplementary Figure 10 Quality control for the Damage-seq data.

a, Values of T-asymmetry. b, Ratio of normalized Damage-seq read density in intergenic regions and genes. c, R-asymmetry. Bars correspond to different replicates.

Supplementary Figure 11 Double staining with Hoechst (green) and EdU (magenta) for each group on the first and second day.

a–h, Groups were stained on the first (a–d) and second (e–h) day. a,e, Control groups; b,f, UV-irradiated groups; c,g, roscovitine-treated groups; d,h, UV-irradiated with roscovitine-treated groups. Scale, 50 µm.

Supplementary Figure 13 Proliferation rate on the first and second day after UV irradiation.

Proliferation was measured as the ratio between the number of EdU-incorporated cells and total cell number. Day 1 and day 2 represent 24 and 48 h after UV irradiation, respectively. Each box plot represents 15 different areas on 3 coverslips (5 areas for each coverslip).

Supplementary Figure 14 Number of mutations and mutational spectra for all replicates obtained in the experiment.

Three of five bar plots were already shown in Fig. 5.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–14, Supplementary Tables 1–3 and Supplementary Notes 1 and 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seplyarskiy, V.B., Akkuratov, E.E., Akkuratova, N. et al. Error-prone bypass of DNA lesions during lagging-strand replication is a common source of germline and cancer mutations. Nat Genet 51, 36–41 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0285-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0285-7

This article is cited by

-

A mutation rate model at the basepair resolution identifies the mutagenic effect of polymerase III transcription

Nature Genetics (2023)

-

Contributions of replicative and translesion DNA polymerases to mutagenic bypass of canonical and atypical UV photoproducts

Nature Communications (2023)

-

In-situ hydrophobic environment triggering reactive fluorescence probe to real-time monitor mitochondrial DNA damage

Frontiers of Chemical Science and Engineering (2022)

-

Somatic genomic changes in single Alzheimer’s disease neurons

Nature (2022)

-

The origin of human mutation in light of genomic data

Nature Reviews Genetics (2021)