Abstract

Psychological research shows that social comparison of individuals with peers or others shapes attitude formation1,2. Opportunities for such comparisons have increased with global inequality3,4; everyday experiences can make economic disparities more salient through signals of social class5,6. Here we show that, among individuals with a lower socioeconomic status, such local exposure to inequality drives support for the redistribution of wealth. We designed a placebo-controlled field experiment conducted in South African neighbourhoods in which individuals with a low socioeconomic status encountered real-world reminders of inequality through the randomized presence of a high-status car. Pedestrians were asked to sign a petition to increase taxes on wealthy individuals to help with the redistribution of wealth. We found an increase of eleven percentage points in the probability of signing the petition in the presence of inequality, when taking into account the experimental placebo effect. The placebo effect suppresses the probability that an individual signs the petition in general, which is consistent with evidence that upward social comparison reduces political efficacy4. Measures of economic inequality were constructed at the neighbourhood level and connected to a survey of individuals with a low socioeconomic status. We found that local exposure to inequality was positively associated with support for a tax on wealthy individuals to address economic disparities. Inequality seems to affect preferences for the redistribution of wealth through local exposure. However, our results indicate that inequality may also suppress participation; the political implications of our findings at regional or country-wide scales therefore remain uncertain.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Research design, protocols, hypotheses and analyses were preregistered before data analysis with EGAP and are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository (https://osf.io/s4bd3). Supporting information is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/C9UQVW. All data necessary to replicate the analyses and figures in this paper and Supplementary Information are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/C9UQVW.

Code availability

All codes necessary to replicate the analyses and figures in this paper and the Supplementary Information are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/C9UQVW. R (open source, version 3.6.1) and Stata (versions 14 and 15) were used for data analysis.

References

Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140 (1954).

Tajfel, H. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1981).

Condon, M. & Wichowsky, A. Inequality in the social mind: perceptions of status and support for redistribution. J. Polit. 82, 149–161 (2020).

Condon, M. & Wichowsky, A. The Economic Other: Inequality in the American Political Imagination (Univ. Chicago Press, 2020).

Kraus, M. W., Rheinschmidt, M. L. & Piff, P. K. in Facing Social Class: How Societal Rank influences Interaction (eds Fiske, S. T. & Markus, H. R.) 152–172 (Russell Sage Foundation, 2012).

Sands, M. L. Exposure to inequality affects support for redistribution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 663–668 (2017).

Côté, S., House, J. & Willer, R. High economic inequality leads higher-income individuals to be less generous. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15838–15843 (2015).

Nishi, A., Shirado, H., Rand, D. G. & Christakis, N. A. Inequality and visibility of wealth in experimental social networks. Nature 526, 426–429 (2015).

Mishra, S. & Hing, L. S. S. & Lalumiere, M. L. Inequality and risk-taking. Evol. Psychol. 13, 1–11 (2015).

Payne, B. K., Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L. & Hannay, J. W. Economic inequality increases risk taking. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4643–4648 (2017).

McCall, L., Burk, D., Laperrière, M. & Richeson, J. A. Exposure to rising inequality shapes Americans’ opportunity beliefs and policy support. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9593–9598 (2017).

Davidai, S. Why do Americans believe in economic mobility? Economic inequality, external attributions of wealth and poverty, and the belief in economic mobility. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 79, 138–148 (2018).

Kuziemko, I., Norton, M. I., Saez, E. & Stantcheva, S. How elastic are preferences for redistribution? Evidence from randomized survey experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 1478–1508 (2015).

Kane, J. V. & Newman, B. J. Organized labor as the new undeserving rich?: Mass media, class-based anti-union rhetoric and public support for unions in the United States. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49 997–1026 (2019).

Bénabou, R. & Tirole, J. Belief in a just world and redistributive politics. Q. J. Econ. 121, 699–746 (2006).

Trump, K.-S. Income inequality influences perceptions of legitimate income differences. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 48, 929–952 (2018).

Trump, K.-S. in Who Gets What? The New Politics of Insecurity (eds Rosenbluth, F. & Weir, M.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, in the press).

DeCelles, K. A. & Norton, M. I. Physical and situational inequality on airplanes predict air rage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5588–5591 (2016).

Kraus, M. W., Park, J. W. & Tan, J. J. X. Signs of social class: the experience of economic inequality in everyday life. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 422–435 (2017).

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W. & Keltner, D. Unpacking the inequality paradox: the psychological roots of inequality and social class. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 57, 53–124 (2018).

Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., Lundberg, K. B. & McKee, S. Political action in the age of high-economic inequality: a multilevel approach. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 11, 232–273 (2017).

Newman, B. J., Shah, S. & Lauterbach, E. Who sees an hourglass? Assessing citizens’ perception of local economic inequality. Res. Polit. 5, 1–7 (2018).

Enos, R. D. The Space between Us: Social Geography and Politics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

Norton, M. I. & Ariely, D. Building a better America—one wealth quintile at a time. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 9–12 (2011).

Niehues, J. Subjective Perceptions of Inequality and Redistributive Preferences: An International Comparison. IW-TRENDS Discussion Paper 2 (Cologne Institute for Economic Research, 2014).

Johnston, C. D. & Newman, B. J. Economic inequality and U.S. public policy mood across space and time. Am. Polit. Res. 44, 164–191 (2016).

Phillips, B. J. Inequality and the emergence of vigilante organizations: the case of Mexican Autodefensas. Comp. Polit. Stud. 50, 1358–1389 (2017).

Pellicer, M., Piraino, P. & Wegner, E. Perceptions of inevitability and demand for redistribution: evidence from a survey experiment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 159, 274–288 (2019).

Cheung, F. Can income inequality be associated with positive outcomes? Hope mediates the positive inequality–happiness link in rural China. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7, 320–330 (2016).

Reyes-García, V., Angelsen, A., Shively, G. E. & Minkin, D. Does income inequality influence subjective wellbeing? Evidence from 21 developing countries. J Happiness Stud. 20, 1197–1215 (2019).

The World Bank. GINI Index (World Bank Estimate). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI (accessed 23 May 2019).

Christopher, A. J. Atlas of Changing South Africa (Routledge, 2002).

Leibbrandt, M., Finn, A. & Woolard, I. Describing and decomposing post-Apartheid income inequality in South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 29, 19–34 (2012).

Fedderke, J. W., de Kadt, R. & Luiz, J. M. Uneducating South Africa: the failure to address the 1910–1993 legacy. Int. Rev. Educ. 46, 257–281 (2000).

Ataguba, J. E.-O., Day, C. & McIntyre, D. Explaining the role of the social determinants of health on health inequality in South Africa. Glob. Health Action 8, 28865 (2015).

Sulla, V. & Zikhali, P. Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An Assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities. (The World Bank, 2018).

South African National Census of 2011. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=3955 (Department of Statistics South Africa, 2011).

Culwick Fatti, C., Götz, G., Jennings, R. & Wray, C. Quality of Life Survey IV (2015/16). https://www.gcro.ac.za/research/project/detail/quality-of-life-survey-iv-2015 (GRCO, 2015).

Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., Lundberg, K. B., Kay, A. C. & Payne, B. K. Subjective status shapes political preferences. Psychol. Sci. 26, 15–26 (2015).

Cruces, G., Perez-Truglia, R. & Tetaz, M. Biased perceptions of income distribution and preferences for redistribution: evidence from a survey experiment. J. Public Econ. 98, 100–112 (2013).

Velez, Y. R. & Wong, G. Assessing contextual measurement strategies. J. Polit. 79, 1084–1089 (2017).

Meltzer, A. H. & Richard, S. F. A rational theory of the size of government. J. Polit. Econ. 89, 914–927 (1981).

Lindert, P. H. Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth Since the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004).

Iversen, T. & Soskice, D. Distribution and redistribution: the shadow of the nineteenth century. World Polit. 61, 438–486 (2009).

Rodden, J. A. Why Cities lose: The Deep Roots of the Urban-Rural Political Divide (Basic Books, 2019).

Reardon, S. F. & Bischoff, K. Income inequality and income segregation. Am. J. Sociol. 116, 1092–1153 (2011).

LoBue, V., Nishida, T., Chiong, C., DeLoache, J. S. & Haidt, J. When getting something good is bad: even three-year-olds react to inequality. Soc. Dev. 20, 154–170 (2011).

Enos, R. D. Causal effect of intergroup contact on exclusionary attitudes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3699–3704 (2014).

Enos, R. D. What the demolition of public housing teaches us about the impact of racial threat on political behavior. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 60, 123–142 (2016).

Dewar, D. in Compact Cities: Sustainable Urban Forms for Developing Countries (eds Jenks, M. & Burgess, R.) 209–218 (Spon, 2000).

Whiteford, A. & Van Seventer, D. Understanding contemporary household inequality in South Africa. J. Stud. Econ. Econ. 24, 7–30 (2000).

Van der Berg, S. et al. Changing patterns of South African income distribution: towards time series estimates of distribution and poverty. S. Afr. J. Econ. 72, 546–572 (2004).

Nattrass, N. & Seekings, J. “Two nations”? Race and economic inequality in South Africa today. Daedalus 130, 45–70 (2001).

Southall, R. The New Black Middle Class in South Africa (Boydell & Brewer, 2016).

Carpenter, D. & Moore, C. D. When canvassers became activists: antislavery petitioning and the political mobilization of American women. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 108, 479–498 (2014).

Parry, J. A., Smith, D. A. & Henry, S. The impact of petition signing on voter turnout. Polit. Behav. 34, 117–136 (2012).

Langa, M. & Kiguwa, P. Violent masculinities and service delivery protests in post-Apartheid South Africa: a case study of two communities in Mpumalanga. Agenda 27, 20–31 (2013).

Alesina, A. & La Ferrara, E. Participation in heterogeneous communities. Q. J. Econ. 115, 847–904 (2000).

Solt, F. Economic inequality and democratic political engagement. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 52, 48–60 (2008).

Soss, J. & Jacobs, L. R. The place of inequality: non-participation in the American polity. Polit. Sci. Q. 124, 95–125 (2009).

Solt, F. Does economic inequality depress electoral participation? Testing the Schattschneider hypothesis. Polit. Behav. 32, 285–301 (2010).

Anderson, C. J. & Beramendi, P. Left parties, poor voters, and electoral participation in advanced industrial societies. Comp. Polit. Stud. 45, 714–746 (2012).

van Holm, E. J. Unequal cities, unequal participation: the effect of income inequality on civic engagement. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 49, 135–144 (2019).

Sunn Bush, S. & Prather, L. Do electronic devices in face-to-face interviews change survey behavior? Evidence from a developing country. Res. Polit. 6, 1–7 (2019).

Struwig, S. & Roberts, B. Heart of the Matter: Nuclear Attitudes in South Africa. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/review/june-2012/heart-of-the-matter-nuclear-attitudes-in-south-africa (The Human Sciences Research Council, 2012).

Franko, W. W. Political context, government redistribution, and the public’s response to growing economic inequality. J. Polit. 78, 957–973 (2016).

Franko, W. W. Understanding public perceptions of growing economic inequality. State Polit. Policy Q. 17, 319–348 (2017).

Cheung, F. & Lucas, R. E. Income inequality is associated with stronger social comparison effects: the effect of relative income on life satisfaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110, 332–341 (2016).

Solt, F., Hu, Y., Hudson, K., Song, J. & Yu, D. E. Economic inequality and class consciousness. J. Polit. 79, 1079–1083 (2017).

Page, L. & Goldstein, D. G. Subjective beliefs about the income distribution and preferences for redistribution. Soc. Choice Welfare 47, 25–61 (2016).

Minkoff, S. L. & Lyons, J. Living with inequality: neighborhood income diversity and perceptions of the income gap. Am. Polit. Res. 47, 329–361 (2017).

Demombynes, G. & Ozler, B. Crime and Local Inequality in South Africa. Research Working Paper WPS 2925 http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/203701468776697701/Crime-and-local-inequality-in-South-Africa (The World Bank, 2002).

Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Xu, Y. How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis 27, 163–192 (2019).

Kenworthy, L. & McCall, L. Inequality, public opinion and redistribution. Socioecon. Rev. 6, 35–68 (2007).

Kelly, N. J. & Enns, P. K. Inequality and the dynamics of public opinion: the self-reinforcing link between economic inequality and mass preferences. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 54, 855–870 (2010).

Newman, B. J., Johnston, C. D. & Lown, P. L. False consciousness or class awareness? Local income inequality, personal economic position, and belief in American meritocracy. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 326–340 (2015).

Allison, P. D. Measures of inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 43, 865–880 (1978).

Cowell, F. Measuring Inequality (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W. & Wooldridge, J. When should you adjust Standard Errors for Clustering? Working Paper 24003 https://www.nber.org/papers/w24003.pdf (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Manyathi and P. Mosia for their work in implementing the field experiment; M. Bryer for her management of the field experiment; J. de Kadt and the Gauteng City-Region Observatory for making the Quality of Life IV module available to us; R. Carney, R. Enos, J. Rodden, J. Trounstine and K.-S. Trump for feedback on drafts of this paper; and the audiences at Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) 24, University of California, Merced, University of California, Berkeley, Stanford University and the Helen Suzman Foundation for feedback. All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and D.d.K. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

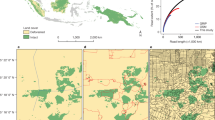

Extended Data Fig. 1 Location of experimental sites within South Africa.

a, Map of Soweto. The seven experimental sites are indicated by blue crosses: Protea Glen, Jabulani Mall, Meadowlands, Dube, Pimville, Kliptown and Diepkloof. b, Map of the greater Johannesburg area, in which Soweto is highlighted by a blue box. c, Map of South Africa, in which Johannesburg is highlighted by a blue box.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Local inequality by SAL for Gauteng.

Local inequality is calculated as the Gini coefficient for each SAL (polygon), using census data from 2011 for the entire Gauteng region obtained from Statistics South Africa.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Personal wealth and the association between the presence of a top-decile household and preferences regarding taxation.

a, A kernel-based nonparametric estimate showing the marginal effect of a change in the presence of a top-decile household in a SAL on the support for a tax on wealthy individuals (y axis) for different levels of wealth (x axis). The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval based on bootstrapped standard errors (n = 19,884, M = 6,775). b, A linear estimate showing the marginal effect of a change in the presence of a top-decile household in a SAL on the support for a tax on wealthy individuals (y axis) for different levels of wealth (x axis). The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors (n = 19,884, M = 6,775). The points are conditional estimates for three terciles of the moderator wealth, low (L), middle (M) and high (H); the red lines show the 95% confidence intervals based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors. Two-sided pairwise tests of the differences between the tercile point estimates yield the following P values for comparisons of low versus middle (P = 0.836), middle versus high (P = 0.167), and low versus high (P = 0.070).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Personal wealth and the association between local Gini inequality and preferences regarding taxation.

a, A kernel-based nonparametric estimate showing the marginal effect of a change in local Gini inequality in a SAL on the support for a tax on wealthy individuals (y axis) for different levels of wealth (x axis). The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors (n = 19,884, M = 6,775). b, A linear estimate showing the marginal effect of a change in local Gini inequality in a SAL on the support for a tax on wealthy individuals (y axis), for different levels of wealth (x axis). The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors (n = 19,884, M = 6,775). The points are conditional estimates for three terciles of the moderator wealth, low, middle and high; the red lines show the 95% confidence intervals based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors. Two-sided pairwise tests of the differences between the tercile point estimates yield the following P values for comparisons of low versus middle (P = 0.657), middle versus high (P = 0.481) and low versus high (P = 0.662).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Personal wealth and the association between local Gini inequality and self-assessed socioeconomic status.

a, A kernel-based nonparametric estimate showing the marginal effect of a change in local Gini inequality in a SAL on self-assessed socioeconomic status (y axis) for different levels of wealth (x axis). The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors (n = 19,884, M = 6,775). b, A linear estimate showing the marginal effect of a change in local Gini inequality in a SAL on self-assessed socioeconomic status (y axis) for different levels of wealth (x axis). The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors (n = 19,884, M = 6,775). The points are conditional estimates for three terciles of the moderator wealth, low, middle and high; the red lines show the 95% confidence intervals based on bootstrapped clustered standard errors. Two-sided pairwise tests of the differences between the tercile point estimates yield the following P values for comparisons of low versus middle (P = 0.657), middle versus high (P = 0.481) and low versus high (P = 0.662).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains supplementary text which includes supplementary figure 1 and supplementary tables 1-32.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sands, M.L., de Kadt, D. Local exposure to inequality raises support of people of low wealth for taxing the wealthy. Nature 586, 257–261 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2763-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2763-1

This article is cited by

-

Fairness and Tax Morale in Developing Countries

Studies in Comparative International Development (2024)

-

Subjective socioeconomic status and income inequality are associated with self-reported morality across 67 countries

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Why are higher-class individuals less supportive of redistribution? The mediating role of attributions for rich-poor gap

Current Psychology (2023)

-

Encounters with inequality lead to demands for taxes on the rich

Nature (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.