Abstract

Despite being only one-atom thick, defect-free graphene is considered to be completely impermeable to all gases and liquids1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. This conclusion is based on theory3,4,5,6,7,8 and supported by experiments1,9,10 that could not detect gas permeation through micrometre-size membranes within a detection limit of 105 to 106 atoms per second. Here, using small monocrystalline containers tightly sealed with graphene, we show that defect-free graphene is impermeable with an accuracy of eight to nine orders of magnitude higher than in the previous experiments. We are capable of discerning (but did not observe) permeation of just a few helium atoms per hour, and this detection limit is also valid for all other gases tested (neon, nitrogen, oxygen, argon, krypton and xenon), except for hydrogen. Hydrogen shows noticeable permeation, even though its molecule is larger than helium and should experience a higher energy barrier. This puzzling observation is attributed to a two-stage process that involves dissociation of molecular hydrogen at catalytically active graphene ripples, followed by adsorbed atoms flipping to the other side of the graphene sheet with a relatively low activation energy of about 1.0 electronvolt, a value close to that previously reported for proton transport11,12. Our work provides a key reference for the impermeability of two-dimensional materials and is important from a fundamental perspective and for their potential applications.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All the mentioned data to support this study and its conclusions are available upon request from P.Z.S. (pengzhan.sun@manchester.ac.uk).

References

Bunch, J. S. et al. Impermeable atomic membranes from graphene sheets. Nano Lett. 8, 2458–2462 (2008).

Berry, V. Impermeability of graphene and its applications. Carbon 62, 1–10 (2013).

Leenaerts, O., Partoens, B. & Peeters, F. M. Graphene: a perfect nanoballoon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 193107 (2008).

Tsetseris, L. & Pantelides, S. T. Graphene: an impermeable or selectively permeable membrane for atomic species? Carbon 67, 58–63 (2014).

Miao, M., Nardelli, M. B., Wang, Q. & Liu, Y. First principles study of the permeability of graphene to hydrogen atoms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 16132–16137 (2013).

Seel, M. & Pandey, R. Proton and hydrogen transport through two-dimensional monolayers. 2D Mater. 3, 025004 (2016).

Feng, Y. et al. Hydrogenation facilitates proton transfer through two-dimensional honeycomb crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 6009–6014 (2017).

Wang, W. L. & Kaxiras, E. Graphene hydrate: theoretical prediction of a new insulating form of graphene. New J. Phys. 12, 125012 (2010).

Koenig, S. P., Wang, L., Pellegrino, J. & Bunch, J. S. Selective molecular sieving through porous graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 728–732 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. Molecular valves for controlling gas phase transport made from discrete ångström-sized pores in graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 785–790 (2015).

Hu, S. et al. Proton transport through one-atom-thick crystals. Nature 516, 227–230 (2014).

Lozada-Hidalgo, M. et al. Sieving hydrogen isotopes through two-dimensional crystals. Science 351, 68–70 (2016).

Bunch, J. S. et al. Electromechanical resonators from graphene sheets. Science 315, 490–493 (2007).

Radha, B. et al. Molecular transport through capillaries made with atomic-scale precision. Nature 538, 222–225 (2016).

Haigh, S. J. et al. Cross-sectional imaging of individual layers and buried interfaces of graphene-based heterostructures and superlattices. Nat. Mater. 11, 764–767 (2012).

Kelly, D. J. et al. Nanometer resolution elemental mapping in graphene-based TEM liquid cells. Nano Lett. 18, 1168–1174 (2018).

Hu, S. et al. Transport of hydrogen isotopes through interlayer spacing in van der Waals crystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 468–472 (2018).

Koenig, S. P., Boddeti, N. G., Dunn, M. L. & Bunch, J. S. Ultrastrong adhesion of graphene membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 543–546 (2011).

Deveau, N. D., Ma, Y. H. & Datta, R. Beyond Sieverts’ law: a comprehensive microkinetic model of hydrogen permeation in dense metal membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 437, 298–311 (2013).

Wu, Q. et al. Selective surface functionalization at regions of high local curvature in graphene. Chem. Commun. 49, 677–679 (2013).

Bissett, M. A., Konabe, S., Okada, S., Tsuji, M. & Ago, H. Enhanced chemical reactivity of graphene induced by mechanical strain. ACS Nano 7, 10335–10343 (2013).

Boukhvalov, D. W. & Katsnelson, M. I. Enhancement of chemical activity in corrugated graphene. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 14176–14178 (2009).

McKay, H., Wales, D. J., Jenkins, S. J., Verges, J. A. & de Andres, P. L. Hydrogen on graphene under stress: molecular dissociation and gap opening. Phys. Rev. B 81, 075425 (2010).

Meyer, J. C. et al. On the roughness of single- and bi-layer graphene membranes. Solid State Commun. 143, 101–109 (2007).

Geringer, V. et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic corrugation of monolayer graphene deposited on SiO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 076102 (2009).

Fasolino, A., Los, J. H. & Katsnelson, M. I. Intrinsic ripples in graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 858–861 (2007).

Kroes, J. M. H., Fasolino, A. & Katsnelson, M. I. Density functional based simulations of proton permeation of graphene and hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 5813–5817 (2017).

Poltavsky, I., Zheng, L., Mortazavi, M. & Tkatchenko, A. Quantum tunneling of thermal protons through pristine graphene. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 204707 (2018).

Mazzuca, J. W. & Haut, N. K. Theoretical description of quantum mechanical permeation of graphene membranes by charged hydrogen isotopes. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 224301 (2018).

Riedl, C., Coletti, C., Iwasaki, T., Zakharov, A. A. & Starke, U. Quasi-free-standing epitaxial graphene on SiC obtained by hydrogen intercalation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 246804 (2009).

Kunc, J., Rejhon, M. & Hlídek, P. Hydrogen intercalation of epitaxial graphene and buffer layer probed by mid-infrared absorption and Raman spectroscopy. AIP Adv. 8, 045015 (2018).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Park, H. G. & Jung, Y. Carbon nanofluidics of rapid water transport for energy applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 565–576 (2014).

Whittaker, J. D., Minot, E. D., Tanenbaum, D. M., McEuen, P. L. & Davis, R. C. Measurement of the adhesion force between carbon nanotubes and a silicon dioxide substrate. Nano Lett. 6, 953–957 (2006).

Hencky, H. Uber den spannungzustand in kreisrunden platten mit verschwindender biegungssteiflgeit. Z. Math. Phys. 63, 311–317 (1915).

Wang, G. et al. Measuring interlayer shear stress in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 036101 (2017).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Course of Theoretical Physics Vol. 5 Statistical Physics 3rd edn (Pergamon Press, 1980).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Kerber, T., Sierka, M. & Sauer, J. Application of semiempirical long-range dispersion corrections to periodic systems in density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 2088–2097 (2008).

Sheppard, D., Xiao, P., Chemelewski, W., Johnson, D. D. & Henkelman, G. A generalized solid-state nudged elastic band method. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 074103 (2012).

Herzberg, G. & Monfils, A. The dissociation energies of the H2, HD, and D2 molecules. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 5, 482–498 (1961).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Hornekær, L. et al. Clustering of chemisorbed H(D) atoms on the graphite (0001) surface due to preferential sticking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 186102 (2006).

Paris, A. et al. Kinetic isotope effect in the hydrogenation and deuteration of graphene. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 1628–1635 (2013).

Bukola, S. & Creager, S. E. A charge-transfer resistance model and Arrhenius activation analysis for hydrogen ion transmission across single-layer graphene. Electrochim. Acta 296, 1–7 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation, the European Research Council (grants ARTIMATTER and VANDER), Graphene Flagship and the Royal Society. S.J.Y. acknowledges support from the National Key R&D Program of China (grant 2018YFA0305800) and Supercomputing Center of Wuhan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.G. suggested and directed the project with help from P.Z.S., Q.Y. and F.C.W. P.Z.S., Q.Y., W.J.K. and Y.V.S. fabricated the devices, performed measurements and analysed the data. W.Q.X., J.Y., M.I.K., S.J.Y. and F.C.W. provided theoretical support. I.V.G., R.R.N, F.C.W. and M.L.-H. contributed to interpretation of the experimental results. A.K.G., P.Z.S., I.V.G. and M.L.-H. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Rohit Karnik, Valentina Tozzini and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

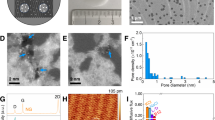

Extended Data Fig. 1 Device fabrication.

a, Graphite or hBN monocrystals are obtained by mechanical exfoliation. Micrometre-size wells are then made by e-beam lithography and ion etching. Monolayer graphene is transferred on top to seal the wells. b, Optical micrograph of a set of hBN microcontainers. The dashed curve indicates the position of monolayer graphene.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Electron micrographs of our microcontainers.

a, A microcontainer with d = 0.5 μm. Such images were taken only after finishing measurements to avoid electron-beam damage. b, Example of a broken graphene seal: the membrane was damaged after a thermal cycle to 80 °C.

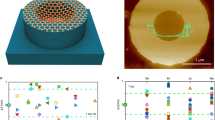

Extended Data Fig. 3 Stability of graphene membranes in air and helium.

a, Changes in δ(0) measured for two containers with d = 1 μm; AFM scans were taken every hour. b, Representative profiles δ(x) for a. c, Long-term variations in δ for 12 different containers kept in air. d, Permeation rates evaluated from the evolution of Δδ with time in c. e, Δδ for 16 different devices placed in helium at 3 bar. f, Permeation rates for the data in e. In c, e, different symbols denote different microcontainers made from graphite (empty symbols) and hBN (solid). The dashed lines in c, e indicate maximum changes detected for representative devices (colour coded). In d, f, the colour represents the same-colour device as in c, e, respectively. Error bars are standard deviation for fitting δ with a linear time dependence. Grey areas are the overall statistical accuracy obtained using all our devices measured in air and helium at 3 bar.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Bilayer graphene and monolayer MoS2 are impermeable to hydrogen.

a, AFM micrographs of the same container sealed with bilayer graphene before (left) and after (right) its exposure to molecular hydrogen at 1 bar at 50 °C for 3 d. White curves show the profiles along the membrane’s diameter. No changes in membrane positions could be detected within our experimental accuracy. b, Same experiment for monolayer MoS2. No changes could be noticed either. c, For comparison, we show the simultaneous experiment for a microcontainer covered with monolayer graphene. The membrane clearly bulged out after the exposure, similar to the case of Fig. 2a. All scale bars, 1 μm. After the experiment, the bulging membrane in c was kept under ambient conditions and found to slowly deflate over months, in agreement with the room-temperature permeation rates reported in the main text.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Pressure dependence of hydrogen permeation.

Symbols are measurements at room temperature. Error bars are standard deviation using a minimum of ten devices in each case. Solid curve is the best fit to the square-root dependence.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Dissociation of molecular hydrogen at graphene ripples.

a, b, Reaction of molecular hydrogen with graphene for t/D = 7.5% if adatoms are adsorbed in the central (a) and bridge (b) positions. Insets: atomic configurations of the initial, maximum-energy and final states (marked by the orange dots). The simulated size D is 2–3 nm. c, The dissociation barrier as a function of ripples’ curvature. Insets show top view of the bridge and central positions for hydrogen adatoms. d, The dissociation energy barrier as a function of biaxial strain. The inset shows schematic showing the direction of applied strain in our simulations.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Intrinsic (dynamic) ripples in graphene at different temperatures.

a, Typical snapshot of graphene membrane at 300 K using molecular dynamics simulations. b, Density of ripples with t/D ≥ 7% (most chemically active). Symbols are the calculations for different T. Solid curve is a guide to the eye. c, Statistical distribution of intrinsic ripples with different t/D.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Isotope effect.

Time evolution of Δδ for ten different devices (different colours) exposed to deuterium at 1 bar at room temperature (295 ± 2 K). All the devices are hBN containers sealed with monolayer graphene. The dashed lines indicate maximum changes detected for the device coded with the same colour. The random fluctuations are close in amplitude to those shown in Fig. 1e for helium.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, P.Z., Yang, Q., Kuang, W.J. et al. Limits on gas impermeability of graphene. Nature 579, 229–232 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2070-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2070-x

This article is cited by

-

Proton transport through nanoscale corrugations in two-dimensional crystals

Nature (2023)

-

Proton and molecular permeation through the basal plane of monolayer graphene oxide

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Rugged bialkali photocathodes encapsulated with graphene and thin metal film

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Gate-controlled suppression of light-driven proton transport through graphene electrodes

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Mechanics of 2D material bubbles

Nano Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.