Abstract

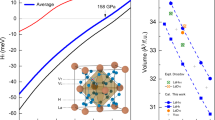

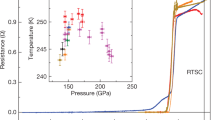

The discovery of superconductivity at 200 kelvin in the hydrogen sulfide system at high pressures1 demonstrated the potential of hydrogen-rich materials as high-temperature superconductors. Recent theoretical predictions of rare-earth hydrides with hydrogen cages2,3 and the subsequent synthesis of LaH10 with a superconducting critical temperature (Tc) of 250 kelvin4,5 have placed these materials on the verge of achieving the long-standing goal of room-temperature superconductivity. Electrical and X-ray diffraction measurements have revealed a weakly pressure-dependent Tc for LaH10 between 137 and 218 gigapascals in a structure that has a face-centred cubic arrangement of lanthanum atoms5. Here we show that quantum atomic fluctuations stabilize a highly symmetrical \({Fm}\overline{3}{m}\) crystal structure over this pressure range. The structure is consistent with experimental findings and has a very large electron–phonon coupling constant of 3.5. Although ab initio classical calculations predict that this \({Fm}\overline{3}{m}\) structure undergoes distortion at pressures below 230 gigapascals2,3, yielding a complex energy landscape, the inclusion of quantum effects suggests that it is the true ground-state structure. The agreement between the calculated and experimental Tc values further indicates that this phase is responsible for the superconductivity observed at 250 kelvin. The relevance of quantum fluctuations calls into question many of the crystal structure predictions that have been made for hydrides within a classical approach and that currently guide the experimental quest for room-temperature superconductivity6,7,8. Furthermore, we find that quantum effects are crucial for the stabilization of solids with high electron–phonon coupling constants that could otherwise be destabilized by the large electron–phonon interaction9, thus reducing the pressures required for their synthesis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All the data generated in this work is available upon request from I.E. and J.A.F.-L.

Code availability

Quantum ESPRESSO is an open-source suite of computational tools available at https://www.quantum-espresso.org. VASP is a proprietary program. The SSCHA and the SCDFT codes are private codes developed by some of the authors, and are being prepared for distribution as an open-source code.

References

Drozdov, A. P., Eremets, M. I., Troyan, I. A., Ksenofontov, V. & Shylin, S. I. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature 525, 73–76 (2015).

Liu, H., Naumov, I. I., Hoffmann, R., Ashcroft, N. W. & Hemley, R. J. Potential high-T c superconducting lanthanum and yttrium hydrides at high pressure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6990–6995 (2017).

Peng, F., Sun, Y., Pickard, C. J., Needs, R. J., Wu, Q. & Ma, Y. Hydrogen clathrate structures in rare earth hydrides at high pressures: possible route to room-temperature superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 107001 (2017).

Somayazulu, M. et al. Evidence for superconductivity above 260 K in lanthanum superhydride at megabar pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 027001 (2019).

Drozdov, A. P. et al. Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures. Nature 569, 528–531 (2019).

Bi, T., Zarifi, N., Terpstra, T. & Zurek, E. The search for superconductivity in high pressure hydrides. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.00163 (2018).

Flores-Livas, J. A., Boeri, L., Sanna, A., Profeta, G., Arita, R. & Eremets, M. A perspective on conventional high-temperature superconductors at high pressure: methods and materials. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.06693 (2019).

Pickard, C. J., Errea, I. & Eremets, M. I. Superconducting hydrides under pressure. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031218-013413 (2019).

Allen, P. B. & Cohen, M. L. Superconductivity and phonon softening. Phys. Rev. Lett. 29, 1593 (1972).

Ashcroft, N. Metallic hydrogen: A high-temperature superconductor? Phys. Rev. Lett. 21, 1748 (1968).

Dias, R. P. & Silvera, I. F. Observation of the Wigner–Huntington transition to metallic hydrogen. Science 355, 715–718 (2017).

Gilman, J. J. Lithium dihydrogen fluoride—an approach to metallic hydrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 26, 546 (1971).

Ashcroft, N. W. Hydrogen dominant metallic alloys: high temperature superconductors? Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 187002 (2004).

Zhang, L., Wang, Y., Lv, J. & Ma, Y. Materials discovery at high pressures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17005 (2017).

Oganov, A. R., Pickard, C. J., Zhu, Q. & Needs, R. J. Structure prediction drives materials discovery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 331–348 (2019).

Li, Y., Hao, J., Liu, H., Li, Y. & Ma, Y. The metallization and superconductivity of dense hydrogen sulfide. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 174712 (2014).

Duan, D. et al. Pressure-induced metallization of dense (H2S)2H2 with high-T c superconductivity. Sci. Rep. 4, 6968 (2014).

Liu, H., Naumov, I. I., Geballe, Z. M., Somayazulu, M., Tse, J. S. & Hemley, R. J. Dynamics and superconductivity in compressed lanthanum superhydride. Phys. Rev. B 98, 100102(R) (2018).

Geballe, Z. M. et al. Synthesis and stability of lanthanum superhydrides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 688–692 (2018).

Hemley, R. J., Ahart, M., Liu, H. & Somayazulu, M. Road to room-temperature superconductivity: T c above 260 K in lanthanum superhydride under pressure. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.03462 (2019).

Benoit, M., Marx, D. & Parrinello, M. Tunnelling and zero-point motion in high-pressure ice. Nature 392, 258–261 (1998).

Errea, I. et al. Quantum hydrogen-bond symmetrization in the superconducting hydrogen sulfide system. Nature 532, 81–84 (2016).

Bianco, R., Errea, I., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. High-pressure phase diagram of hydrogen and deuterium sulfides from first principles: structural and vibrational properties including quantum and anharmonic effects. Phys. Rev. B 97, 214101 (2018).

Goedecker, S. Minima hopping: an efficient search method for the global minimum of the potential energy surface of complex molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 9911 (2004).

Bianco, R., Errea, I., Paulatto, L., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Second-order structural phase transitions, free energy curvature, and temperature-dependent anharmonic phonons in the self-consistent harmonic approximation: theory and stochastic implementation. Phys. Rev. B 96, 014111 (2017).

Monacelli, L., Errea, I., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Pressure and stress tensor of complex anharmonic crystals within the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024106 (2018).

Liu, L., Wang, C., Yi, S., Kim, K. W., Kim, J. & Cho, J.-H. Microscopic mechanism of room-temperature superconductivity in compressed LaH10. Phys. Rev. B 99, 140501 (2019).

Troyan, I. A. et al. Synthesis and superconductivity of yttrium hexahydride \(Im\overline{3}m\)-YH6. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.01534 (2019).

Semenok, D. V. et al. Superconductivity at 161 K in thorium hydride ThH10: synthesis and properties. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.10206 (2019).

Kong, P. P. et al. Superconductivity up to 243 K in yttrium hydrides under high pressure. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.10482 (2019).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515 (2001).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with QUANTUM ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Errea, I., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. First-principles theory of anharmonicity and the inverse isotope effect in superconducting palladium-hydride compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 177002 (2013).

Errea, I., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Anharmonic free energies and phonon dispersions from the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation: application to platinum and palladium hydrides. Phys. Rev. B 89, 064302 (2014).

Amsler, M. & Goedecker, S. Crystal structure prediction using the minima hopping method. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 224104 (2010).

Flores-Livas, J. A., Sanna, A. & Gross, E. K. U. High temperature superconductivity in sulfur and selenium hydrides at high pressure. Eur. Phys. J. B 89, 63 (2016).

Flores-Livas, J. A. et al. Superconductivity in metastable phases of phosphorus-hydride compounds under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 93, 020508 (2016).

Flores-Livas, J. A. et al. Interplay between structure and superconductivity: metastable phases of phosphorus under pressure. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 024802 (2017).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Oliveira, L. N., Gross, E. K. U. & Kohn, W. Density-functional theory for superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2430 (1988).

Lüders, M. et al. Ab initio theory of superconductivity. I. Density functional formalism and approximate functionals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024545 (2005).

Flores-Livas, J. A. & Sanna, A. Superconductivity in intercalated group-IV honeycomb structures. Phys. Rev. B 91, 054508 (2015).

Pellegrini, C., Glawe, H. & Sanna, A. Density functional theory of superconductivity in doped tungsten oxides. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 064804 (2019).

Marques, M. A. L. et al. Ab initio theory of superconductivity. II. Application to elemental metals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024546 (2005).

Linscheid, A., Sanna, A., Floris, A. & Gross, E. K. U. First-principles calculation of the real-space order parameter and condensation energy density in phonon-mediated superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 097002 (2015).

Massidda, S. et al. The role of Coulomb interaction in the superconducting properties of CaC6 and H under pressure. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 22, 034006 (2009).

Sanna, A. et al. Ab initio Eliashberg theory: making genuine predictions of superconducting features. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 041012 (2018).

Sano, W., Koretsune, T., Tadano, T., Akashi, R. & Arita, R. Effect of Van Hove singularities on high-T c superconductivity in H3S. Phys. Rev. B 93, 094525 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 802533); the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (FIS2016-76617-P); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (number 16H06345, 18K03442 and 19H05825) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan; and NCCR MARVEL funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Computational resources were provided by the Barcelona Superconducting Center (project FI-2019-1-0031) and the Swiss National Supercomputing Center (CSCS) with project s970.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by I.E. and J.A.F.-L. The SSCHA was developed by I.E., L.M., R.B., M.C. and F.M. In particular, R.B. developed the method to compute the quantum energy Hessian and the anharmonic phonon dispersions, and L.M. developed the method to perform a quantum relaxation of the lattice parameters. I.E. and F.B. performed the SSCHA calculations. A.S., T.K., T.T., R.A. and J.A.F.-L. conducted studies on structure prediction and superconductivity. All authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Yanming Ma and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Convex hull of enthalpy formation and diffraction pattern of candidate LaH10 phases.

Top, classical calculations of enthalpy (without zero-point energy) at different hydrogen contents at 100, 150 and 200 GPa. At low pressure (100 GPa), LaH10 is not stable and only develops as stable point in the convex hull of enthalpy formation at pressures above about 175 GPa. Bottom, diffraction patterns of different structures at 150 GPa (classical pressure), compared to the experimental data reported in ref. 5 for LaH10 in the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) phase at 150 GPa. The pattern is shown in the vicinity of the (111) peak of the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) phase. This peak is clearly split in the distorted C2 and \(R\bar{3}m\) phases predicted classically. The figure provides confirmation that the experimental resolution in ref. 5 would have been sufficient to distinguish between these phases.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Convergence of SSCHA-phonon supercells and different anharmonic phonon calculations for LaH10 at 163 GPa.

Left, the phonon spectra shown are calculated by directly Fourier-interpolating the force constants obtained from the Hessian of \(E({\boldsymbol{ {\mathcal R} }})\) in a real space 2 × 2 × 2 and a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell. The similarity of both phonon spectra obtained by Fourier interpolation indicates that these SSCHA force constants are short-ranged and can be Fourier-interpolated. Right, phonon spectra obtained from the SSCHA energy Hessian of equation (1), making different level of approximations. The purple solid line is the phonon spectrum calculated with the full-energy Hessian without any approximation. In the blue dotted spectrum we set \(\mathop{\varPhi }\limits^{(4)}\) = 0 in the equation. For the orange dash-dotted line we set \(\mathop{\varPhi }\limits^{(3)}=\mathop{\varPhi }\limits^{(4)}=0\), so that the phonon spectra correspond to that arising directly from the SSCHA variational force constants Φ. These results clearly show that whereas the effect of \(\mathop{\varPhi }\limits^{(3)}\) is important, setting \(\mathop{\varPhi }\limits^{(4)}\) = 0 has minimal effect. All phonon spectra are obtained by directly Fourier-interpolating the real space anharmonic force constants in a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell.

Extended Data Fig. 3 α2F(ω) values for the \({\boldsymbol{Fm}}\overline{3}{\boldsymbol{m}}\) phase of LaH10 and LaD10.

Calculated α2F(ω) values for different pressures together with the integrated electron–phonon coupling constant, which is defined as \(\lambda (\omega )=2{\int }_{0}^{\omega }{\rm{d}}\varOmega {\alpha }^{2}F(\varOmega )/\varOmega \). The results show that high frequency, optical modes of hydrogen are responsible for the large value of the electron–phonon coupling constant λ. It is worth noting that acoustic modes with La character contribute between 0.2 and 0.5 to λ and cannot be neglected when aiming to estimate an accurate value of Tc.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Details of the \({\boldsymbol{R}}\overline{3}{\boldsymbol{m}}\) LaH10 cell relaxation, including quantum effects.

The initial point for the relaxation is the output from the previous internal relaxation with fixed angle presented in Extended Data Fig. 5. The \(R\bar{3}m\) phase in the rhombohedral description is described by three vectors of the same length (a = b = c) and by the angles between them (α = β = γ). The top left panel shows the evolution of the rhombohedral angle and the top right panel shows the evolution of the rhombohedral lattice parameter (a = b = c). The progression of the stress tensor in the quantum SSCHA minimization is shown in the bottom left panel. It is clear that at the end of the minimization the structure has an angle of 60°, which matches the angle of an fcc lattice and, in this case, the stress is isotropic. In the bottom right panel, we show the evolution of the Wyckoff positions in the minimization and we compare it with that of the \(Fm\bar{3}m\)phase. The occupied Wyckoff positions for both \(R\bar{3}m\) LaH10 and \(Fm\bar{3}m\) LaH10 are summarized in Extended Data Table 2. Here, the evolution of εa, εb, εx and εy parameters in the minimization can be seen. The atoms in the first set of 6c positions approach the 8c Wyckoff site of the \(Fm\bar{3}m\)phase, whereas the atoms in the second set of 6c positions and those in 18h sites approach the atoms in the 32f Wyckoff site of the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) phase, where ε = 0.12053.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Phonon dispersion in \({\boldsymbol{R}}\overline{3}{\boldsymbol{m}}\)-phase LaH10 and the anisotropic pressure created in a fixed-cell quantum relaxation.

Left, harmonic and anharmonic phonon spectrum, maintaining a 62.3° rhombohedral angle. The harmonic calculation is performed with the internal atomic positions that yield classical vanishing forces. The anharmonic calculation is performed after relaxing (with the SSCHA) the internal degrees of freedom but maintaining the 62.3° rhombohedral angle. At the harmonic level there are unstable phonon modes even at Γ. Symmetry prevents the relaxation of this structure according to the unstable phonon mode at Γ. The harmonic phonons are calculated at a classic pressure of 150 GPa. Quantum effects add around an extra 10 GPa to the pressure. To the right of the graph is shown the behaviour of λ(ω) and α2F(ω) for the anharmonic calculation. Right, pressure along the different Cartesian directions during the SSCHA relaxation of the internal parameters, keeping the rhombohedral angle fixed at 62.3°. At step 0 the pressure reported is obtained directly from V(R), neglecting quantum effects. It is isotropic within 1 GPa of difference between the x–y and z directions. At each of the other steps it is calculated from the quantum \(E({\boldsymbol{ {\mathcal R} }})\) and along the minimization it becomes anisotropic. When the minimization stops at step 12—that is, the internal coordinates are at the minimum of the \(E({\boldsymbol{ {\mathcal R} }})\) for this lattice—the stress anisotropy between the z and the x–y directions is about 6%. This clearly indicates that quantum effects act to relax the crystal lattice—in particular, because Pz is larger—by reducing the rhombohedral angle. It is worth noting that quantum effects increase the total pressure by approximately 10 GPa, which is calculated as P = (Px + Py + Pz)/3. The initial cell parameters before the minimization are a = 3.5473398 Å and α = 62.34158°. The initial values of the free Wyckoff parameters, which yield classical vanishing forces and a 150-GPa isotropic stress, are εa = 0.26043, εb = 0.09950, εx = 0.10746 and εy = 0.12810. See Extended Data Table 2 for more details.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Anisotropic pressure of the C2 phase of LaH10 in a cell quantum relaxation.

Pressure along the different Cartesian directions is plotted during the SSCHA cell minimization. The target pressure for this minimization is 160 GPa. At the end of the minimization the isotropy of the stress tensor is recovered. A symmetry analysis performed on the structure at the end of the minimization confirms that the C2 LaH10 evolves in the \(Fm\bar{3}m\)-phase LaH10. The initial values Px = 163.2 GPa, Py = 159.7 GPa, Pz = 155.0 GPa are obtained by an atomic internal relaxation performed using the SSCHA with a fixed cell.

Extended Data Fig. 7 SSCHA minimization on LaH10 and DOS.

Top left and top right, two initial structures (C2 and \(R\bar{3}m\)) of low enthalpy that were considered in our SSCHA simulations. When considering quantum effects, both structures evolve towards the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) structure. The corresponding total electronic DOS at different pressures is plotted for each structure (for comparison, at the same energy scale). The highly symmetric motif \((Fm\bar{3}m)\) maximizes \({N}_{{E}_{F}}\), whereas in distorted structures (\(R\bar{3}m\) and C2) the occupation at the Fermi level is reduced by more than 23% for C2 and by 11% for \(R\bar{3}m\) (with respect to \(Fm\bar{3}m\) at 150 GPa). Values at classical pressures are shown for comparison. Note that the shape of the DOS plot is also strongly modified at different pressures.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Details of LaH11.

Left, crystal structure of the P4/nmm phase of LaH11 at 100 GPa, which is thermodynamically stable in the convex hull. Top right, dispersion of harmonic phonons along the momentum space for LaH11: it is dynamically stable. Bottom right, superconducting Eliashberg spectrum function (α2F(ω)) calculated for LaH11 at the pressure indicated with harmonic phonons. The Tc estimated using the Allen–Dynes formula (μ* = 0.1) is around 7 K at 100 GPa (harmonic phonons).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Errea, I., Belli, F., Monacelli, L. et al. Quantum crystal structure in the 250-kelvin superconducting lanthanum hydride. Nature 578, 66–69 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1955-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1955-z

This article is cited by

-

Full-bandwidth anisotropic Migdal-Eliashberg theory and its application to superhydrides

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Prediction of ambient pressure conventional superconductivity above 80 K in hydride compounds

npj Computational Materials (2024)

-

Temperature and quantum anharmonic lattice effects on stability and superconductivity in lutetium trihydride

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Enhancement of superconducting properties in the La–Ce–H system at moderate pressures

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Quantum phase diagram of high-pressure hydrogen

Nature Physics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.