Abstract

There have been several major outbreaks of emerging viral diseases, including Hendra, Nipah, Marburg and Ebola virus diseases, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)—as well as the current pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Notably, all of these outbreaks have been linked to suspected zoonotic transmission of bat-borne viruses. Bats—the only flying mammal—display several additional features that are unique among mammals, such as a long lifespan relative to body size, a low rate of tumorigenesis and an exceptional ability to host viruses without presenting clinical disease. Here we discuss the mechanisms that underpin the host defence system and immune tolerance of bats, and their ramifications for human health and disease. Recent studies suggest that 64 million years of adaptive evolution have shaped the host defence system of bats to balance defence and tolerance, which has resulted in a unique ability to act as an ideal reservoir host for viruses. Lessons from the effective host defence of bats would help us to better understand viral evolution and to better predict, prevent and control future viral spillovers. Studying the mechanisms of immune tolerance in bats could lead to new approaches to improving human health. We strongly believe that it is time to focus on bats in research for the benefit of both bats and humankind.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The current pandemic of COVID-19—caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)—has led to more than 75,704,857 cases and caused 1,690,061 deaths (as of 21 December 2020)1. Although the possibility of an intermediate host remains an open question, SARS-CoV-2 is believed to have an ancestral origin in bats2—with closest similarity to the bat coronavirus RaTG133. Conceptually, an outbreak caused by an emerging zoonotic bat virus has not only been predicted, but expected4,5,6. Continued human interference with natural ecosystems has resulted in many outbreaks in the past few decades6. Along with well-known bat-borne viruses such as rabies and Ebola virus7,8, there is a range of diverse coronaviruses in bats that have confirmed spillover potential for severe disease outbreaks—including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (which emerged in 2003) and ongoing outbreaks associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (since 2012). The ability of bats to harbour many viruses—and zoonotic coronaviruses in particular—may result from their ability to efficiently regulate host responses to infection, although species richness may also have a role9. Through ecological factors, biological traits or their underlying unique immune systems, bats can prevent excessive immune pathology in response to most viral pathogens. Examining these processes will unlock key lessons for human health, from understanding ageing to combating cancer and infectious diseases.

Basic biology of bats

Across mammalian orders, Chiroptera (bats) is a species-rich taxon that stands out as it is uniquely capable of powered flight; bats represent 1,423 of the more than 6,400 known species of mammal10,11 (Table 1). This diversity is matched by their wide geographical distribution, which spares only the polar regions, extreme desert climates and a few oceanic islands12. Bats are keystone species upon which other fauna and flora are highly dependent for fertilization, pollination, seed dispersal and control of insect populations13,14. Bats roost in foliage, rock crevices and caves, and hollowed trees, as well as human-made structures such as barns, houses and bridges15. Different species may be homo- or heterothermic, using hibernation or shorter, daily episodic torpor to conserve energy16. Bats are prone to low fecundity and use reproductive strategies such as the storage of sperm or prolonged pregnancies, with either seasonal or aseasonal reproductive cycles15. Furthermore, they consume a wide range of diets—including nectar, fruit, pollen, insects, fish and blood (as in the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus)). Ever intriguing to humankind, bats possess the sensing powers of echolocation and magnetoreception (the ability to differentiate polar south from north), both of which are used primarily by microbats17,18,19. Differences in ecology, biology and physiology are important factors that must be considered in species-specific responses within bats and in the conduction of experimental studies.

Despite the advantages and efficiency of aerial transport, flight is a metabolically costly mode of locomotion20: the metabolic rates of bats in flight can reach up to 2.5–3× those of similar-sized exercising terrestrial mammals21. This enormous energy demand results in the depletion of up to 50% of their stored energy in a day—nectarivorous bats catabolize their high-energy diet of simple sugars as rapidly as 8 min after consumption, and flying bats consume about 1,200 calories of energy per hour22,23,24. Bats possess several metabolic adaptations and optimized airflow patterns to circumvent high-energy expenditures that could otherwise lead to starvation and death25. A key adaptation is the marked alteration of heart rate, which increases by 4–5× during flight to a maximum of 1,066 beats per minute24. To compensate for high levels of cardiac stress, cyclic bradycardia is induced for 5–7 min several times per hour during rest, which may conserve up to 10% of available energy. Despite their high metabolic rates and small statures, bats live substantially longer than non-flying mammals of similar body mass26,27. When adjusted for body size, only 19 species of mammals are longer-lived than humans: 18 of these species are bats (the other is the naked mole-rat)28. On average, the maximum recorded lifespan of bats is 3.5× that of a non-flying placental mammal of a similar size29. As a mammalian model of antiageing, bats may offer vital clues in human attempts to delay mortality and enhance longevity.

Status of bats as a unique viral reservoir

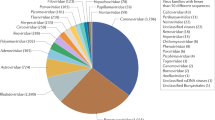

Bats have been associated with infectious diseases for centuries. Their role in the transmission of rabies virus led Metchnikov to investigate fruit bat macrophages and their immune responses in 190930. More recently, several new or re-emerging viral outbreaks associated with spillover from bat reservoirs have been documented, and a number of reports have highlighted the risk of future spillover events into human populations. Enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA coronaviruses are widespread in animals (54% of those known are associated with bats), and cause mild-to-severe respiratory or enteric disease in humans31. The association between coronaviruses and bats began to be recognized with the discovery of SARS-related coronaviruses in bats32,33,34,35. Since then, bats have been identified as the richest source of genetically diverse coronaviruses36, including the MERS-CoV-like viruses37 and a range of bat coronaviruses38,39,40. Several genome sequences of bat coronaviruses have recently been reported that show a high genetic similarity to SARS-CoV-23,41. The increasing number of spillover events of bat viruses—and of coronaviruses in particular—is believed to stem from the disruption of the natural ecosystems that host bats through climate change, increased urbanization pressure from humans, wildlife trade and animal markets34,42,43 (Fig. 1). Some large global initiatives have been funded to examine the risk factors for potential spillover events, but the funding of this area of research has been reduced in recent years44,45. Although an event such as COVID-19 has increasingly been anticipated, few scientists would have expected the magnitude and speed of spread of this current pandemic.

Coronaviruses may transmit naturally (black arrows) among humans, bats and other wildlife (such as racoon dogs, hedgehogs, pangolins, palm civets, camels (as is known for MERS-CoV) and mink)158. Human interventions may amplify the spread (red arrow). Transmission cycles may be amplified in urban areas that are normally at a minimal risk of exposure, increasing transmission to humans and accelerating an outbreak scenario. (1) Natural zoonotic infection cycles from domestic animals or wildlife (including bats) to humans and vice versa; human populations at risk include bat guano farmers, or individuals living and working in areas that overlap with bat habitats. (2) Natural enzootic cycle between different species of wildlife (including bats), and domestic animals and wildlife. (3) Amplification and spread between overlapping bat populations—as, for example, seen among species in the Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae for SARS-related coronaviruses159. (4) Amplified zoonotic infections and spread to urban areas via human interventions, including wildlife trade and increased urbanization. (5) Anthropozoonotic infections from humans back to domestic animals or wildlife (for example, as in mink farming50). (6) Human migration patterns facilitate spread to urban areas (for example, during holiday seasons160). (7) Amplified viral spread among humans or animals and humans in dense urban settings.

It should also be emphasized that bat-borne viruses cause devastating outbreaks not only in humans, but also in animals such as pigs and horses46,47,48,49. During a large-scale outbreak (as with the current COVID-19 pandemic), there is a risk of spillback or ‘reverse’ zoonotic (anthropozoonotic) transmission from human to animals, as has been demonstrated by COVID-19 outbreaks in minks on two farms in the Netherlands, followed by animal-to-human transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus50. Anthropozoonotic infections of SARS-CoV-2 have also been observed from pet owners to domestic cats and dogs51,52, and to tigers and lions housed in zoos53. There is a predicted risk of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 to other free-ranging mammalian wildlife, including the great apes54 and bats in different geographical locations55, and this perceived threat has affected the wildlife tourism industry in many countries. Although intermediate hosts such as civets and pangolins have been implicated in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks (respectively), these animals exhibited pulmonary oedema and inflammation in response to infection with SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses56,57,58, which suggests that they are not true reservoirs for these coronaviruses. By contrast, bats lack clinical signs of disease when infected with the majority of viruses, although there are some rare exceptions. High-titre infection with Tacaribe virus59 or infection with species-divergent strains of lyssavirus60 can cause severe symptoms and death. The filovirus Lloviu virus is associated with the death of bats in Spain61 and the fungal white-nose syndrome kills bats by affecting energy needs as bats awake from hibernation or torpor62.

The unique status of bats as a viral reservoir is further confirmed by the fact that bats host more zoonotic pathogens than any other known mammalian species63,64,65. Previous reviews have discussed the biological traits of these flying mammals and how these traits may empower bats to act as exceptional reservoirs4,6,66,67,68. Some putative explanations for reservoir potential propose that immune variation during hibernation69 or the higher temperatures that bats experience during flight (in the ‘fever’ hypothesis70) decrease viral loads and therefore maintain their status as a viral reservoir. However, studies on bat cells grown at high temperatures do not show a decrease in viral titres compared to cells grown at 37 °C71. In addition, these hypotheses have lost traction recently as more studies indicate a tolerance of virus infection rather than an active reduction of viral load. Recent work on bat metabolism, mitochondrial dynamics, innate and adaptive immunity and links between metabolic and immune systems have provided insights into the potential dynamic responses in bats. What makes bats special might not be their antiviral ability, but rather their antidisease features72,73,74. Here we hypothesize that the unique balance between host defence and immune tolerance in bats may be responsible for the special relationship between bats and viruses (particularly coronaviruses).

A balanced host defence–tolerance system

Homeostasis is the ultimate state of health for any living system, from cells to human bodies, and obtaining homeostasis requires the constant adjustment of biochemical and physiological pathways. For example, the maintenance of a constant blood pressure results from fine adjustments to and balancing of many coordinated functions that include hormonal, neuromuscular and cardiovascular systems. This is also true of an effective host defence system. Although an appropriate level of defence is required to combat pathogens and diseases, excessive or dysregulated responses lead to cellular damage and tissue pathology. Many emerging bat-borne viruses—including SARS-CoV and Ebola virus—are highly pathogenic in humans, which correlates with an aberrant innate immune activation with prolonged and/or stronger immune responses75,76,77,78. By contrast, infected bats show no or minimal signs of disease even when high viral titres are detected in tissues or sera, which suggests that they are tolerant of viral diseases79,80,81,82. Recent studies have provided insights into the mechanisms used by bats to fine-tune a balance between protective versus pathological responses, which may contribute to their extraordinarily long lifespans and low incidence of cancer (Fig. 2).

Bats show an excellent balance between enhanced host defence responses and immune tolerance through several mechanisms. Examples of enhanced host defences include constitutive expression of IFNs and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), increased expression of heat-shock proteins (HSPs), a higher base level expression of the efflux pump ABCB1 and enhanced autophagy. On the other hand, dampened STING and suppressed inflammasome pathways—such as dampened NLRP3, loss of PYHIN and downstream IL-1β—contribute to immune tolerance in bats.

Enhanced host defence responses

The unique status of bats as a viral reservoir has triggered increasing interest and efforts to characterize the immune system of bats. Earlier efforts focused on genomic73,83 and transcriptomic analysis84,85,86, and particularly on interferon and antiviral activities87,88,89,90. Humans express minimal baseline levels of type I interferons (IFNs), and they are highly inducible upon stimulation91. By comparison, the black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) constitutively expresses some baseline IFNα, and many species of bats express several IFN-stimulated genes before stimulation84,89,92,93. This may be regulated by IFN regulatory factors (IRFs), as differential expression patterns of IRF794 and enhanced IRF3-mediated antiviral responses95 are observed in bats. The restricted induction of type I IFNs would minimize production of inflammatory cytokines93. The kinetics of the IFN response in bats also differs from those of other mammals, with a faster decline phase for some bat interferon-stimulated genes88. In addition, several antiviral genes—such as RNASEL88,90—are IFN-induced in bats but not in other mammals84,93 or have undergone selection pressure to potentially alter function, such as those encoding Mx proteins96 and APOBEC397. Antiviral immune activation in bats has also previously been reviewed98,99. Just as IFN signalling varies across mammals100, there is likewise variation in the IFN response across bat species. For instance, P. alecto shows a contraction of an IFN locus89, whereas the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) exhibits no constitutive IFN but has one markedly expanded IFN locus—especially for IFNω73. Several species suggest a restricted induction profile of IFNα and IFNβ compared to human or mouse84,92,93. Dysregulation of the IFN response has previously been implicated in autoimmune diseases101 and the pathogenesis of several bat-borne viruses, including Ebola virus76, SARS-CoV75,76,77 and SARS-CoV-2102,103. Together, these bat-specific changes in baseline expression, kinetics, induction or functions of antiviral genes in IFN signalling could help bats to efficiently control the numerous viruses that they host.

In addition to the innate immune responses, recent studies have shed light on other mechanisms of bat host defence. Enhanced autophagy has a key role in the increased clearance of lyssavirus from bat cells104, and is known to regulate immunity and mediate pathogen clearance105. Bats express very high levels of heat-shock proteins, which confers upon bat cells the ability to survive at high temperature and high oxidative stress in vitro. Heat-shock proteins contribute to the rapid acceleration of viral evolution by chaperoning viral proteins and tolerating some viral mutations106. They also act as a viral receptor107, regulate inflammation108, block apoptosis109 and affect ageing110.

Common to all bats yet examined, mitochondrial and nuclear oxidative phosphorylation genes show evidence of specific adaptive evolutionary changes that support the large metabolic demands associated with flight99,111. Bats also have a concentration of positively selected genes in the DNA-damage checkpoint pathways that are important for cell death, cancer and ageing, in addition to the innate immune pathways83. A recent study has demonstrated that efficient drug efflux through the ABCB1 transporter in bats blocked DNA damage induced by the chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and etoposide, conferring resistance to genotoxic compounds, regulating cellular homeostasis and possibly lowering the incidence of cancer112. Bats have a reduced production of reactive oxygen species compared to similar-sized non-flying mammals, but retain intact activity of the important antioxidant superoxide dismutase113,114. These findings suggest either a more effective scavenging of reactive oxygen species or a lower production of reactive oxygen species by bat mitochondria: a recent study has confirmed decreased generation of reactive oxygen species in bats, without the age-dependent decline of antireactive oxygen species defence seen in mice115.

Mechanisms of immune tolerance

Both naturally infected and experimentally infected bats indicate tolerance of viral infection, even during a transient phase of high viral titres79,80,81,82. For instance, the infection of bats with high doses of Ebola virus79 and MERS-CoV81 caused minimal or no clinical disease, although titres can reach as high as 107 fluorescent focus-forming units per millilitre of sera for Ebola virus and 107 median tissue-culture infectious dose (50% reduction) equivalents per gram of lung tissues for MERS-CoV. This supports an immunological tolerance to RNA viruses in bats, particularly during the acute response. These observations have triggered increasing efforts to study how bats limit excessive or aberrant innate immunue responses. From the initial characterization of two divergent bat genomes83 and through more recent genome additions73,116,117, a consistent trend for the evolution of immune-related genes—including those encoding the pattern recognition receptors—has been revealed. Pattern recognition receptors sense endogenous molecules from damaged cells and structurally conserved microbial structures, known as damage and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, respectively118. The recognition of viral invasion by these pattern recognition receptors and their downstream signalling are key first-line defences119. The first mechanistic study of immune tolerance in bats showed that the STING-dependent type I IFN response was dampened in several bat species, and that this results from a point mutation of a highly conserved residue of STING87. STING is an important pattern recognition receptor that mediates cytosolic-DNA-induced signalling and has a key role in infection, inflammation and cancer120. This mutation might be driven evolutionarily to tolerate the overactivation of STING by host DNA damage that is induced by flight. However, the effect of dampened STING on responses to infection with bat-borne RNA viruses—which might activate STING by inducing host DNA damage121—is yet to be understood.

A more recent study has revealed a key mechanism by which bats naturally dampen host inflammation in response to ‘sterile’ danger signals and infections with three types of RNA virus (including MERS-CoV)72. NLR-family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3), a key inflammasome sensor that recognizes various cellular stresses and pathogen invasions, is dampened at both the transcription and protein level in bats. Importantly, reduced NLRP3-mediated inflammatory responses to RNA viruses have no, or minimal, effect on viral loads. This supports an enhanced innate immune tolerance in bats, which is consistent with their unique status as an asymptomatic viral reservoir. As NLRP3 is increasingly recognized as sensing a broad range of emerging viruses122 (including MERS-CoV72 and SARS-CoV123,124), this mechanism may have a wide application in the great variety of bat-borne viruses (including SARS-CoV-2)125,126. In addition to NLRP3, an earlier study reported the unique loss of the entire PYHIN gene family at the genomic level in bats127. The members of the PYHIN gene family (also known as AIM2-like receptors) including AIM2 and IFI16 are recognized as the only inflammasome sensors for intracellular DNA, of both self and microbial origins128. Both NLRP3 and AIM2 converge on their downstream effector caspase-1, which is responsible for cleavage of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, and simultaneously unleashes inflammatory cell death (pyroptosis) through GSDMD129,130. Recent data reveal additional mechanisms of dampening at the level of downstream caspase-1 and IL-1β131, demonstrating a unique targeting of the inflammasome pathway for inhibition in bats. The high metabolic demands of flight could—in theory—lead to the release of metabolic by-products, including reactive oxygen species, ATP, damaged DNA and other danger signals that are known to trigger inflammasome activation. Therefore, adaptions to flight could have driven the different mechanisms of dampening in bats, which in turn limits excessive virus-induced or age-related inflammation: this could subsequently contribute to the tolerance of viral infection and increased lifespan of bats.

Other studies have provided more insight into the immune tolerance of bats, although these lack functional validation or examination across several bat species. Treatment with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid—a double-stranded RNA ligand—in cells of the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) did not elicit a robust TNF induction, owing to a c-Rel motif in the promoter region132. However, this might be a species-specific and/or ligand-specific observation, as this motif is not detected in the TNF promoter region of P. alecto and TNF production was observed with other ligands72. An inhibitory immune state of natural killer cells has been inferred from genome analysis of natural killer cell receptors, providing support for enhanced immune tolerance73. In a bat–mouse chimaera model, an immunodeficient mouse reconstituted with a bat immune system appeared to be less prone to graft-versus-host disease than were other chimeric mouse systems reconstituted with immune cells from human and other mammalian animal donors133. Although the detailed immune-tolerance mechanism(s) is yet to be elucidated, the observation is consistent with other discoveries relating to bats having a defence–tolerance system that is more balanced than is typical among mammals.

In summary, the overall enhanced host-defence responses—coupled with immune tolerance or dampening—seem to provide a tight balance in how bats respond to stresses, which is elegantly demonstrated in their responses to viral infections. In addition, evolutionary studies have revealed several genes or pathways that are under strong positive selection in bats, which require further functional investigation. These include the nucleic-acid-sensing Toll-like receptors (another group of pattern recognition receptors), which might reflect altered sensing of pathogens134. There is evidence for adaptive evolution in bat cGAS–STING and OAS–RNase L pathways, which potentially alter the ability of bats to activate IFN in response to cellular nucleic acids87,135. Pteropus alecto MHC-I molecules exhibit a unique isoform with a three-amino-acid insertion within their peptide-binding groove that leads to distinct peptide binding motifs with a preference for proline at the PΩ site136. This unique peptide-binding preference is not responsible for the ability of P. alecto MHC-I to accommodate N-terminally extended peptides of up to 15-mers137. Other bat species show a similar three- or five-amino-acid insertion, a feature that is not shared by most other mammals and that may confer advantageous T cell immunity136,138,139. Although the genomic characterization and evolutionary studies of bat MHC-II genes have previously been described, further laboratory investigation is required to evaluate any functional differences from those of other mammals140,141.

Learning from bats

Research in bats and viruses of the past few decades has strengthened the notion that bats are indeed ‘special’ as reservoir hosts for emerging viruses. The next important question revolves around discerning what makes bats special. The unique balance of enhanced host-defence responses and immune tolerance through several mechanisms might be the key to this question. Deeper understanding will provide insights and strategies not only to aid in the prediction, prevention or control of zoonotic virus spillover from bats to humans, but also to potentially combat ageing and cancer in humans. Furthermore, the effect of altered bat immunity on viral evolution may cause enhanced virulence after spillover into hosts with divergent immune systems142. One of the key findings that has previously been highlighted is the dampened activation of the inflammasome complex in bats. Previous studies have demonstrated altered inflammasome activation in bats, including the loss of the PYHIN gene family127, dampened NLRP372 and reduced function of caspase-1 and/or IL-1β131 (Fig. 3). Importantly, the breadth of inflammasome-driven diseases in humans is notable, and often involves excessive activation of this pathway. These diseases include—but are not limited to—autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, infectious diseases and several age-related diseases (such as metabolic diseases and neurodegenerative diseases)143. Mechanistic studies of immune tolerance may reveal key regulatory factors for the development of targets and strategies to limit harmful inflammatory responses in humans. A genome-wide comparison of immune-related genes reveals that the phylogenetic relationship between bats and humans is closer than that between humans and rodents144. This greater similarity consolidates bats as potentially representing powerful model species for the study of viral diseases, ageing and cancer, promoting the translation of findings in bats into clinically relevant treatments.

a, In human or mouse, pattern recognition receptor (PRR) priming and subsequent activation by RNA viruses, danger signals or intracellular double-stranded DNA activate the NLRP3 or AIM2 inflammasome with intact ASC speck formation, pyroptosis and IL-1β secretion. b, By contrast, bats have dampened transcriptional priming (1) and reduced protein function (2) for NLRP3, loss of PYHIN including AIM2 (3), and reduced caspase-1 activity (4) and/or IL-1β cleavage (5), which leads to an overall reduction in inflammation.

One of the major challenges for studying bat biology and immunology is that—as they are not yet model species—there are limited tools and reagents for bats. Recent efforts to characterize the bat immune system have led to developments of more bat-specific research tools, including antibodies for immune-cell markers144,145 and protocols for the differentiation of primary immune cells146. In addition, newly developed in vivo animal models include a bat–mouse chimaera model133 and transgenic or knock-in mouse models that contain a bat gene. Several research groups now also have captive bat colonies. These are invaluable in investigating the mechanisms of host defence or tolerance and facilitating the translation of lessons from bats. With the establishment of further reagents and tools for bats, we are confident that a deeper understanding of what makes bats special will provide insights and strategies to combat infection, ageing and other inflammatory diseases in humans.

Conclusions

A few decades ago, no one would have predicted that bat research would gain the momentum it has now. In addition to flight, various biological traits make bats unique among mammals. Endeavours such as those of the Bat1K consortium147, and technologies such as single-cell RNA sequencing, will allow unbiased and deeper characterization of bats, bat immune-cell populations and their specific functions and pathways. The host defence–immune tolerance balance of bats confers exceptional health. The identification of the key regulators and machinery that are involved in maintaining this homeostatic balance would provide valuable lessons for controlling and combating viruses, cancer, ageing and numerous inflammatory diseases in humans. Viruses do not recognize borders—and neither do bats. An increased awareness of bat research in alignment with translational outcomes for humans and international solidarity in laboratory and field-based research efforts is needed. By understanding the source of emerging viruses and harnessing knowledge from nature, we can develop approaches to improving the global One Health status148.

References

WHO. COVID-19 Status Report https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed 21 December 2020).

Andersen, K. G., Rambaut, A., Lipkin, W. I., Holmes, E. C. & Garry, R. F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 26, 450–452 (2020).

Zhou, P. et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). This key virology paper details the isolation and characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the current outbreak of COVID-19 and a closely related bat CoV.

Calisher, C. H., Childs, J. E., Field, H. E., Holmes, K. V. & Schountz, T. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 531–545 (2006). The first comprehensive review on bats as a unique reservoir source of emerging viruses, which provides a summary that remains highly cited and relevant to this day.

Smith, I. & Wang, L. F. Bats and their virome: an important source of emerging viruses capable of infecting humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 3, 84–91 (2013).

Wang, L. F. & Anderson, D. E. Viruses in bats and potential spillover to animals and humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 34, 79–89 (2019).

Enright, J. B., Sadler, W. W., Moulton, J. E. & Constantine, D. Isolation of rabies virus from an insectivorous bat (Tadarida mexicana) in California. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 89, 94–96 (1955).

Goldstein, T. et al. The discovery of Bombali virus adds further support for bats as hosts of ebolaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 1084–1089 (2018).

Mollentze, N. & Streicker, D. G. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9423–9430 (2020).

Simmons, N. B. & Cirranello, A. L. Bat Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Database https://batnames.org/ (accessed 12 August 2020).

Upham, N. et al. Mammal Diversity Database version 1.2 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4139818 (2020).

Nowak, R. M. & Walker, E. P. Walker’s Bats of the World (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1994).

Jones, K. E. (ed.) in Encyclopedia of Life Sciences https://doi.org/10.1038/npg.els.0004129 (Wiley, 2006).

Voigt, C. C. & Kingston, T. Bats in the Anthropocene (Springer International, 2015).

Kunz, T. H. Ecology of Bats (Springer US, 1982).

Geiser, F. & Stawski, C. Hibernation and torpor in tropical and subtropical bats in relation to energetics, extinctions, and the evolution of endothermy. Integr. Comp. Biol. 51, 337–348 (2011).

Jones, G. & Holderied, M. W. Bat echolocation calls: adaptation and convergent evolution. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 274, 905–912 (2007).

Springer, M. S., Teeling, E. C., Madsen, O., Stanhope, M. J. & de Jong, W. W. Integrated fossil and molecular data reconstruct bat echolocation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6241–6246 (2001).

Wang, Y., Pan, Y., Parsons, S., Walker, M. & Zhang, S. Bats respond to polarity of a magnetic field. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 274, 2901–2905 (2007).

Alexander, R. M. The merits and implications of travel by swimming, flight and running for animals of different sizes. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 1060–1064 (2002).

Thomas, S. P. Metabolism during flight in two species of bats, Phyllostomus hastatus and Pteropus gouldii. J. Exp. Biol. 63, 273–293 (1975).

Voigt, C. C. & Speakman, J. R. Nectar-feeding bats fuel their high metabolism directly with exogenous carbohydrates. Funct. Ecol. 21, 913–921 (2007).

Kelm, D. H., Simon, R., Kuhlow, D., Voigt, C. C. & Ristow, M. High activity enables life on a high-sugar diet: blood glucose regulation in nectar-feeding bats. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 278, 3490–3496 (2011).

O’Mara, M. T. et al. Cyclic bouts of extreme bradycardia counteract the high metabolism of frugivorous bats. eLife 6, e26686 (2017).

Muijres, F. T. et al. Leading-edge vortex improves lift in slow-flying bats. Science 319, 1250–1253 (2008).

Austad, S. N. & Fischer, K. E. Mammalian aging, metabolism, and ecology: evidence from the bats and marsupials. J. Gerontol. 46, B47–B53 (1991).

Podlutsky, A. J., Khritankov, A. M., Ovodov, N. D. & Austad, S. N. A new field record for bat longevity. J. Gerontol. A 60, 1366–1368 (2005).

Austad, S. N. Methusaleh’s Zoo: how nature provides us with clues for extending human health span. J. Comp. Pathol. 142, S10–S21 (2010).

Wilkinson, G. S. & South, J. M. Life history, ecology and longevity in bats. Aging Cell 1, 124–131 (2002).

Metchnikoff, E., Weinberg, M., Pozerski, E., Distaso, A. & Berthelot, A. Rousettes et microbes. Ann. Inst. Pasteur (Paris) 23, 61 (1909).

ICTV. Virus Taxonomy https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy (accessed 21 May 2020).

Lau, S. K. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14040–14045 (2005). A highly cited paper in the field that revealed bats as the natural reservoir of SARS-related coronaviruses, which opened up an era of research into bats and coronaviruses.

Ge, X. Y. et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 503, 535–538 (2013).The product of ten years of intensive research, this study confirmed the presence of SARS-CoV in bats and their potential to infect humans, which is of contemporary relevance for the current pursuit of the origins of SARS-CoV-2.

Li, W. et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 310, 676–679 (2005).

Poon, L. L. et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in bats. J. Virol. 79, 2001–2009 (2005).

Banerjee, A., Kulcsar, K., Misra, V., Frieman, M. & Mossman, K. Bats and coronaviruses. Viruses 11, 41 (2019).

Woo, P. C. Y., Lau, S. K. P., Li, K. S. M., Tsang, A. K. L. & Yuen, K. Y. Genetic relatedness of the novel human group C betacoronavirus to Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4 and Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 1, e35 (2012).

Cui, J., Li, F. & Shi, Z. L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 181–192 (2019).

Fan, Y., Zhao, K., Shi, Z. L. & Zhou, P. Bat coronaviruses in China. Viruses 11, 210 (2019).

Hu, B. et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006698 (2017).

Zhou, H. et al. A novel bat coronavirus closely related to SARS-CoV-2 contains natural insertions at the S1/S2 cleavage site of the spike protein. Curr. Biol. 30, 2196–2203.e3 (2020).

Cheng, V. C., Lau, S. K., Woo, P. C. & Yuen, K. Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an agent of emerging and reemerging infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 660–694 (2007).

Latinne, A. et al. Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. Nat. Commun. 11, 4235 (2020).

Cima, G. Pandemic prevention program ending after 10 years. JAVMAnews https://www.avma.org/javma-news/2020-01-15/pandemic-prevention-program-ending-after-10-years (2 January 2020).

Wadman, M. & Cohen, J. NIH’s axing of bat coronavirus grant a ‘horrible precedent’ and might break rules, critics say. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc5616 (30 April 2020).

Murray, K. et al. A morbillivirus that caused fatal disease in horses and humans. Science 268, 94–97 (1995).

Chua, K. B. et al. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science 288, 1432–1435 (2000).

Zhou, P. et al. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature 556, 255–258 (2018).

Huang, Y. W. et al. Origin, evolution, and genotyping of emergent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains in the United States. MBio 4, e00737-13 (2013).

Oreshkova, N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, the Netherlands, April and May 2020. EuroSurveill. 25, 2001005 (2020).

Abdel-Moneim, A. S. & Abdelwhab, E. M. Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 infection of animal hosts. Pathogens 9, 529 (2020).

Sit, T. H. C. et al. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 586, 776–778 (2020).

Newman, A. et al. First reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in companion animals – New York, March–April 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 710–713 (2020).

Gillespie, T. R. & Leendertz, F. H. COVID-19: protect great apes during human pandemics. Nature 579, 497 (2020).

Olival, K. J. et al. Possibility for reverse zoonotic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to free-ranging wildlife: a case study of bats. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008758 (2020).

Xiao, Y. et al. Pathological changes in masked palm civets experimentally infected by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus. J. Comp. Pathol. 138, 171–179 (2008).

Lam, T. T. et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature 583, 282–285 (2020).

Xiao, K. et al. Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins. Nature 583, 286–289 (2020).

Cogswell-Hawkinson, A. et al. Tacaribe virus causes fatal infection of an ostensible reservoir host, the Jamaican fruit bat. J. Virol. 86, 5791–5799 (2012).

Freuling, C. et al. Experimental infection of serotine bats (Eptesicus serotinus) with European bat lyssavirus type 1a. J. Gen. Virol. 90, 2493–2502 (2009).

Negredo, A. et al. Discovery of an ebolavirus-like filovirus in Europe. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002304 (2011).

Frick, W. F., Puechmaille, S. J. & Willis, C. K. R. in Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of Bats in a Changing World (eds Voigt, C. & Kingston, T.) 245–262 (Springer, 2015).

Luis, A. D. et al. A comparison of bats and rodents as reservoirs of zoonotic viruses: are bats special? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 280, 20122753 (2013).

Brook, C. E. & Dobson, A. P. Bats as ‘special’ reservoirs for emerging zoonotic pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 23, 172–180 (2015).

Olival, K. J. et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature 546, 646–650 (2017). A landmark study that used host traits (such as environmental factors, host taxonomy and human presence within the range of a host species) to demonstrate that—out of all mammalian orders—bats contain the largest proportion of zoonotic viruses.

Wang, L.-F., Walker, P. J. & Poon, L. L. Mass extinctions, biodiversity and mitochondrial function: are bats ‘special’ as reservoirs for emerging viruses? Curr. Opin. Virol. 1, 649–657 (2011).

Plowright, R. K. et al. Ecological dynamics of emerging bat virus spillover. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 282, 20142124 (2015). A comprehensive review that discusses a variety of ecological drivers of zoonotic spillover and potential risk factors.

Han, H. J. et al. Bats as reservoirs of severe emerging infectious diseases. Virus Res. 205, 1–6 (2015).

Bouma, H. R., Carey, H. V. & Kroese, F. G. Hibernation: the immune system at rest? J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 619–624 (2010).

O’Shea, T. J. et al. Bat flight and zoonotic viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 741–745 (2014).

Miller, M. R. et al. Broad and temperature independent replication potential of filoviruses on cells derived from Old and New World bat species. J. Infect. Dis. 214, S297–S302 (2016).

Ahn, M. et al. Dampened NLRP3-mediated inflammation in bats and implications for a special viral reservoir host. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 789–799 (2019). A functional study that demonstrates lowered activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome sensor in bats with a reduced response to both ‘sterile’ and zoonotic viral infection, mechanistically identifying dampened transcriptional priming, a novel splice variant and functional activity of bat NLRP3.

Pavlovich, S. S. et al. The Egyptian rousette genome reveals unexpected features of bat antiviral immunity. Cell 173, 1098–1110 (2018).An important bat genomics paper that reveals potential mechanisms of host tolerance.

Hayman, D. T. S. Bat tolerance to viral infections. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 728–729 (2019).

Cameron, M. J., Bermejo-Martin, J. F., Danesh, A., Muller, M. P. & Kelvin, D. J. Human immunopathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Virus Res. 133, 13–19 (2008).

Liu, X. et al. Transcriptomic signatures differentiate survival from fatal outcomes in humans infected with Ebola virus. Genome Biol. 18, 4 (2017).

Totura, A. L. & Baric, R. S. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 264–275 (2012).

Zampieri, C. A., Sullivan, N. J. & Nabel, G. J. Immunopathology of highly virulent pathogens: insights from Ebola virus. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1159–1164 (2007).

Swanepoel, R. et al. Experimental inoculation of plants and animals with Ebola virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2, 321–325 (1996).

Watanabe, S. et al. Bat coronaviruses and experimental infection of bats, the Philippines. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16, 1217–1223 (2010).

Munster, V. J. et al. Replication and shedding of MERS-CoV in Jamaican fruit bats (Artibeus jamaicensis). Sci. Rep. 6, 21878 (2016).

Middleton, D. J. et al. Experimental Nipah virus infection in pteropid bats (Pteropus poliocephalus). J. Comp. Pathol. 136, 266–272 (2007).

Zhang, G. et al. Comparative analysis of bat genomes provides insight into the evolution of flight and immunity. Science 339, 456–460 (2013). The first comparative bat genomics study, which revealed various highly selected, missing or altered genes that have diverse roles in the mammalian DNA damage, innate immune and oxidative phosphorylation pathways and opened up various avenues for further discoveries in bats.

Glennon, N. B., Jabado, O., Lo, M. K. & Shaw, M. L. Transcriptome profiling of the virus-induced innate immune response in Pteropus vampyrus and its attenuation by Nipah virus interferon antagonist functions. J. Virol. 89, 7550–7566 (2015).

Wynne, J. W. et al. Proteomics informed by transcriptomics reveals Hendra virus sensitizes bat cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Genome Biol. 15, 532 (2014).

Papenfuss, A. T. et al. The immune gene repertoire of an important viral reservoir, the Australian black flying fox. BMC Genomics 13, 261 (2012).

Xie, J. et al. Dampened STING-dependent interferon activation in bats. Cell Host Microbe 23, 297–301 (2018). An important experimental study that showed reduced signalling by the intracellular sensor, STING, of bats, owing to a replacement—across all bat species—of a serine residue (S358) that is highly conserved in other mammals; this replacement results in the loss of interferon production and antiviral activity.

De La Cruz-Rivera, P. C. et al. The IFN response in bats displays distinctive IFN-stimulated gene expression kinetics with atypical RNASEL induction. J. Immunol. 200, 209–217 (2018).

Zhou, P. et al. Contraction of the type I IFN locus and unusual constitutive expression of IFN-α in bats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2696–2701 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. IFNAR2-dependent gene expression profile induced by IFN-α in Pteropus alecto bat cells and impact of IFNAR2 knockout on virus infection. PLoS ONE 12, e0182866 (2017).

McNab, F., Mayer-Barber, K., Sher, A., Wack, A. & O’Garra, A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 87–103 (2015).

Shaw, A. E. et al. Fundamental properties of the mammalian innate immune system revealed by multispecies comparison of type I interferon responses. PLoS Biol. 15, e2004086 (2017).

Hölzer, M. et al. Virus- and interferon alpha-induced transcriptomes of cells from the microbat Myotis daubentonii. iScience 19, 647–661 (2019).

Zhou, P. et al. IRF7 in the Australian black flying fox, Pteropus alecto: evidence for a unique expression pattern and functional conservation. PLoS ONE 9, e103875 (2014).

Banerjee, A. et al. Positive selection of a serine residue in bat IRF3 confers enhanced antiviral protection. iScience 23, 100958 (2020).

Fuchs, J. et al. Evolution and antiviral specificities of interferon-induced Mx proteins of bats against Ebola, influenza, and other RNA viruses. J. Virol. 91, e00361-17 (2017).

Hayward, J. A. et al. Differential evolution of antiretroviral restriction factors in pteropid bats as revealed by APOBEC3 gene complexity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1626–1637 (2018).

Banerjee, A. et al. Novel insights into immune systems of bats. Front. Immunol. 11, 26 (2020).

Subudhi, S., Rapin, N. & Misra, V. Immune system modulation and viral persistence in bats: understanding viral spillover. Viruses 11, 192 (2019).

Secombes, C. J. & Zou, J. Evolution of interferons and interferon receptors. Front. Immunol. 8, 209 (2017).

Malireddi, R. K. & Kanneganti, T. D. Role of type I interferons in inflammasome activation, cell death, and disease during microbial infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3, 77 (2013).

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020).

Tay, M. Z., Poh, C. M., Rénia, L., MacAry, P. A. & Ng, L. F. P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 363–374 (2020).

Laing, E. D. et al. Enhanced autophagy contributes to reduced viral infection in black flying fox cells. Viruses 11, 260 (2019).

Kuballa, P., Nolte, W. M., Castoreno, A. B. & Xavier, R. J. Autophagy and the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 611–646 (2012).

Phillips, A. M. et al. Host proteostasis modulates influenza evolution. eLife 6, e28652 (2017).

Reyes-del Valle, J., Chávez-Salinas, S., Medina, F. & Del Angel, R. M. Heat shock protein 90 and heat shock protein 70 are components of dengue virus receptor complex in human cells. J. Virol. 79, 4557–4567 (2005).

Srivastava, P. Roles of heat-shock proteins in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 185–194 (2002).

Beere, H. M. et al. Heat-shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis by preventing recruitment of procaspase-9 to the Apaf-1 apoptosome. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 469–475 (2000).

Singh, R. et al. Heat-shock protein 70 genes and human longevity: a view from Denmark. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1067, 301–308 (2006).

Shen, Y. Y. et al. Adaptive evolution of energy metabolism genes and the origin of flight in bats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8666–8671 (2010).

Koh, J. et al. ABCB1 protects bat cells from DNA damage induced by genotoxic compounds. Nat. Commun. 10, 2820 (2019).

Brunet-Rossinni, A. K. Reduced free-radical production and extreme longevity in the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) versus two non-flying mammals. Mech. Ageing Dev. 125, 11–20 (2004).

Ungvari, Z. et al. Oxidative stress in vascular senescence: lessons from successfully aging species. Front. Biosci. 13, 5056–5070 (2008).

Vyssokikh, M. Y. et al. Mild depolarization of the inner mitochondrial membrane is a crucial component of an anti-aging program. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 6491–6501 (2020).

Chattopadhyay, B., Garg, K. M., Ray, R., Mendenhall, I. H. & Rheindt, F. E. Novel de novo genome of Cynopterus brachyotis reveals evolutionarily abrupt shifts in gene family composition across fruit bats. Genome Biol. Evol. 12, 259–272 (2020).

Hawkins, J. A. et al. A metaanalysis of bat phylogenetics and positive selection based on genomes and transcriptomes from 18 species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 11351–11360 (2019).

Takeuchi, O. & Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140, 805–820 (2010).

Iwasaki, A. A virological view of innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66, 177–196 (2012).

Barber, G. N. STING: infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 760–770 (2015).

Li, N. et al. Influenza infection induces host DNA damage and dynamic DNA damage responses during tissue regeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 2973–2988 (2015).

Lupfer, C., Malik, A. & Kanneganti, T. D. Inflammasome control of viral infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 12, 38–46 (2015).

Chen, I. Y., Moriyama, M., Chang, M. F. & Ichinohe, T. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus viroporin 3a activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Microbiol. 10, 50 (2019).

Nieto-Torres, J. L. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus E protein transports calcium ions and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Virology 485, 330–339 (2015).

Yaqinuddin, A. & Kashir, J. Novel therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2-induced acute lung injury: targeting a potential IL-1β/neutrophil extracellular traps feedback loop. Med. Hypotheses 143, 109906 (2020).

Freeman, T. L. & Swartz, T. H. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in severe COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 11, 1518 (2020).

Ahn, M., Cui, J., Irving, A. T. & Wang, L. F. Unique loss of the PYHIN gene family in bats amongst mammals: implications for inflammasome sensing. Sci. Rep. 6, 21722 (2016).

Schattgen, S. A. & Fitzgerald, K. A. The PYHIN protein family as mediators of host defenses. Immunol. Rev. 243, 109–118 (2011).

Lamkanfi, M. & Dixit, V. M. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell 157, 1013–1022 (2014). A key review paper in the field of inflammasome biology.

Wang, K. et al. Structural mechanism for GSDMD targeting by autoprocessed caspases in pyroptosis. Cell 180, 941–955 (2020).

Goh, G. et al. Complementary regulation of caspase-1 and IL-1β reveals additional mechanisms of dampened inflammation in bats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 28939–28949 (2020).

Banerjee, A., Rapin, N., Bollinger, T. & Misra, V. Lack of inflammatory gene expression in bats: a unique role for a transcription repressor. Sci. Rep. 7, 2232 (2017).

Yong, K. S. M. et al. Bat–mouse bone marrow chimera: a novel animal model for dissecting the uniqueness of the bat immune system. Sci. Rep. 8, 4726 (2018).

Escalera-Zamudio, M. et al. The evolution of bat nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors. Mol. Ecol. 24, 5899–5909 (2015).

Mozzi, A. et al. OASes and STING: adaptive evolution in concert. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 1016–1032 (2015).

Lu, D. et al. Peptide presentation by bat MHC class I provides new insight into the antiviral immunity of bats. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000436 (2019).

Wynne, J. W. et al. Characterization of the antigen processing machinery and endogenous peptide presentation of a bat MHC class I molecule. J. Immunol. 196, 4468–4476 (2016).

Ng, J. H. et al. Evolution and comparative analysis of the bat MHC-I region. Sci. Rep. 6, 21256 (2016).

Qu, Z. et al. Structure and peptidome of the bat MHC class I molecule reveal a novel mechanism leading to high-affinity peptide binding. J. Immunol. 202, 3493–3506 (2019).

Salmier, A., de Thoisy, B., Crouau-Roy, B., Lacoste, V. & Lavergne, A. Spatial pattern of genetic diversity and selection in the MHC class II DRB of three Neotropical bat species. BMC Evol. Biol. 16, 229 (2016).

Ng, J. H. J., Tachedjian, M., Wang, L. F. & Baker, M. L. Insights into the ancestral organisation of the mammalian MHC class II region from the genome of the pteropid bat, Pteropus alecto. BMC Genomics 18, 388 (2017).

Brook, C. E. et al. Accelerated viral dynamics in bat cell lines, with implications for zoonotic emergence. eLife 9, e48401 (2020).

Guo, H., Callaway, J. B. & Ting, J. P. Inflammasomes: mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat. Med. 21, 677–687 (2015).

Gamage, A. M. et al. Immunophenotyping monocytes, macrophages and granulocytes in the pteropodid bat Eonycteris spelaea. Sci. Rep. 10, 309 (2020).

Edenborough, K. M. et al. Dendritic cells generated from Mops condylurus, a likely filovirus reservoir host, are susceptible to and activated by Zaire ebolavirus infection. Front. Immunol. 10, 2414 (2019).

Zhou, P. et al. Unlocking bat immunology: establishment of Pteropus alecto bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and macrophages. Sci. Rep. 6, 38597 (2016).

Jebb, D. et al. Six reference-quality genomes reveal evolution of bat adaptations. Nature 583, 578–584 (2020).

Gibbs, E. P. J. The evolution of One Health: a decade of progress and challenges for the future. Vet. Rec. 174, 85–91 (2014).

Teeling, E. C. et al. A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science 307, 580–584 (2005). A comprehensive time-scale analysis of the molecular phylogeny of all extant bats that validated the Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera suborders, predicted the common ancestor of bats and suggests that their evolutionary origins were in Laurasia (possibly North America).

McCracken, G. F. in Monitoring Trends in Bat populations of the US and Territories: Problems and Prospects. United States Geological Survey, Biological Resources Discipline, Information and Technology Report, USGS/BRD/ITR-2003–003 (eds O’Shea, T. J. & Bogan, M. A.) 21–30 (US Geological Survey, 2003).

Norris, D. O. & Lopez, K. H. Hormones and Reproduction of Vertebrates Vol. 1 (Academic, 2010).

Burbank, R. C. & Young, J. Z. Temperature changes and winter sleep of bats. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 82, 459–467 (1934).

Dietz, C. & Kiefer, A. Bats of Britain and Europe (Bloomsbury, 2016).

Reeder, W. G. & Cowles, R. B. Aspects of thermoregulation in bats. J. Mamm. 32, 389–403 (1951).

Davis, W. H. & Reite, O. B. Responses of bats from temperate regions to changes in ambient temperature. Biol. Bull. 132, 320–328 (1967).

Ossa, G., Kramer-Schadt, S., Peel, A. J., Scharf, A. K. & Voigt, C. C. The movement ecology of the straw-colored fruit bat, Eidolon helvum, in sub-Saharan Africa assessed by stable isotope ratios. PLoS ONE 7, e45729 (2012).

Morrison, P. & McNab, B. K. Temperature regulation in some Brazilian phyllostomid bats. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 21, 207–221 (1967).

Johansen, M. D. et al. Animal and translational models of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19. Mucosal Immunol. 13, 877–891 (2020).

Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 536–544 (2020).

Fan, C. et al. Prediction of epidemic spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus driven by spring festival transportation in China: a population-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 1679 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Research in the group of L.-F.W. is supported by grants from the Singapore National Research Foundation (NRF2012NRF-CRP001-056 and NRF2016NRF-NSFC002-013), the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (MOH-OFIRG19MAY-0011 and COVID19RF-003) and the Ministry of Education Singapore (MOE2019-T2-2-130). A.T.I. is supported by National Medical Research Council of Singapore (NMRC/BNIG/2040/2015) and a Zhejiang University special scientific research fund for COVID-19 prevention and control.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.-F.W. conceived the idea for this manuscript. A.T.I. provided the first draft. M.A. and G.G. contributed considerably to the bat biology and host defence–immune tolerance sections. D.E.A. contributed to the virus-related sections. All authors were involved in the final editing and approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Fabian Leendertz, Silke Stertz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Irving, A.T., Ahn, M., Goh, G. et al. Lessons from the host defences of bats, a unique viral reservoir. Nature 589, 363–370 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03128-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03128-0

This article is cited by

-

Coordinated inflammatory responses dictate Marburg virus control by reservoir bats

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Evaluation of Mastadenovirus and Rotavirus Presence in Phyllostomid, Vespertilionid, and Molossid Bats Captured in Rio Grande do Sul, Southern Brazil

Food and Environmental Virology (2024)

-

Molecular evidence of Borrelia spp. in bats from Córdoba Department, northwest Colombia

Parasites & Vectors (2023)

-

Roles of host proteases in the entry of SARS-CoV-2

Animal Diseases (2023)

-

Bats live with dozens of nasty viruses — can studying them help stop pandemics?

Nature (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.