Abstract

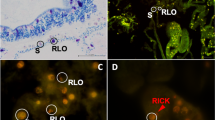

Apicomplexa is a group of obligate intracellular parasites that includes the causative agents of human diseases such as malaria and toxoplasmosis. Apicomplexans evolved from free-living phototrophic ancestors, but how this transition to parasitism occurred remains unknown. One potential clue lies in coral reefs, of which environmental DNA surveys have uncovered several lineages of uncharacterized basally branching apicomplexans1,2. Reef-building corals have a well-studied symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic Symbiodiniaceae dinoflagellates (for example, Symbiodinium3), but the identification of other key microbial symbionts of corals has proven to be challenging4,5. Here we use community surveys, genomics and microscopy analyses to identify an apicomplexan lineage—which we informally name ‘corallicolids’—that was found at a high prevalence (over 80% of samples, 70% of genera) across all major groups of corals. Corallicolids were the second most abundant coral-associated microeukaryotes after the Symbiodiniaceae, and are therefore core members of the coral microbiome. In situ fluorescence and electron microscopy confirmed that corallicolids live intracellularly within the tissues of the coral gastric cavity, and that they possess apicomplexan ultrastructural features. We sequenced the genome of the corallicolid plastid, which lacked all genes for photosystem proteins; this indicates that corallicolids probably contain a non-photosynthetic plastid (an apicoplast6). However, the corallicolid plastid differs from all other known apicoplasts because it retains the four ancestral genes that are involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Corallicolids thus share characteristics with both their parasitic and their free-living relatives, which suggests that they are evolutionary intermediates and implies the existence of a unique biochemistry during the transition from phototrophy to parasitism.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The following are deposited in GenBank: the Rhodactis sp. wkC1 mitochondrial genome (accession number MH320096); corallicolid 18S, 5.8S and 28S rRNA genes from Rhodactis sp. wkC1 (MH304760, MH304761), Orbicella sp. TRC (MH304758) and Cyphastrea sp. 2 (MH304759); corallicolid mitochondrial genomes from Rhodactis sp. wkC1 (MH320093), Orbicella sp. 8CC (MH320094) and Cyphastrea sp. 2 (MH320095); and the corallicolid plastid genome from Rhodactis sp. wkC1 (MH304845).

The 18S rRNA and 16S rRNA gene amplicon reads are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA482746).

References

Janouškovec, J., Horák, A., Barott, K. L., Rohwer, F. L. & Keeling, P. J. Global analysis of plastid diversity reveals apicomplexan-related lineages in coral reefs. Curr. Biol. 22, R518–R519 (2012).

Mathur, V., del Campo, J., Kolisko, M. & Keeling, P. J. Global diversity and distribution of close relatives of apicomplexan parasites. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 2824–2833 (2018).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 28, 2570–2580 (2018).

Hernandez-Agreda, A., Gates, R. D. & Ainsworth, T. D. Defining the core microbiome in corals’ microbial soup. Trends Microbiol. 25, 125–140 (2017).

Ainsworth, T. D., Fordyce, A. J. & Camp, E. F. The other microeukaryotes of the coral reef microbiome. Trends Microbiol. 25, 980–991 (2017).

Lim, L. & McFadden, G. I. The evolution, metabolism and functions of the apicoplast. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 365, 749–763 (2010).

Moore, R. B. et al. A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites. Nature 451, 959–963 (2008).

Oborník, M. et al. Morphology, ultrastructure and life cycle of Vitrella brassicaformis n. sp., n. gen., a novel chromerid from the Great Barrier Reef. Protist 163, 306–323 (2012).

Woo, Y. H. et al. Chromerid genomes reveal the evolutionary path from photosynthetic algae to obligate intracellular parasites. eLife 4, e06974 (2015).

Cumbo, V. R. et al. Chromera velia is endosymbiotic in larvae of the reef corals Acropora digitifera and A. tenuis. Protist 164, 237–244 (2013).

Janouškovec, J., Horák, A., Barott, K. L., Rohwer, F. L. & Keeling, P. J. Environmental distribution of coral-associated relatives of apicomplexan parasites. ISME J. 7, 444–447 (2013).

Mohamed, A. R. et al. Deciphering the nature of the coral–Chromera association. ISME J. 12, 776–790 (2018).

Upton, S. & Peters, E. A new and unusual species of coccidium (Apicomplexa: Agamococcidiorida) from Caribbean scleractinian corals. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 47, 184–193 (1986).

Toller, W. W., Rowan, R. & Knowlton, N. Genetic evidence for a protozoan (phylum Apicomplexa) associated with corals of the Montastraea annularis species complex. Coral Reefs 21, 143–146 (2002).

Šlapeta, J. & Linares, M. C. Combined amplicon pyrosequencing assays reveal presence of the apicomplexan “type-N” (cf. Gemmocystis cylindrus) and Chromera velia on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. PLoS ONE 8, e76095 (2013).

Clerissi, C. et al. Protists within corals: the hidden diversity. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2043 (2018).

Hernandez-Agreda, A., Leggat, W., Bongaerts, P., Herrera, C. & Ainsworth, T. D. Rethinking the coral microbiome: simplicity exists within a diverse microbial biosphere. Mbio 9, e00812–e00818 (2018).

Lang, J. Interspecific aggression by scleractinian corals: 2. Why the race is not only to the swift. Bull. Mar. Sci. 23, 260–279 (1973).

Janouškovec, J., Horák, A., Oborník, M., Lukes, J. & Keeling, P. J. A common red algal origin of the apicomplexan, dinoflagellate, and heterokont plastids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10949–10954 (2010).

Dontsova, O. A. & Dinman, J. D. 5S rRNA: structure and function from head to toe. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 1, 1–7 (2005).

Barbrook, A. C., Voolstra, C. R. & Howe, C. J. The chloroplast genome of a Symbiodinium sp. clade C3 isolate. Protist 165, 1–13 (2014).

Smith, D. R. Plastid genomes hit the big time. New Phytol. 219, 491–495 (2018).

Kirk, N. L. et al. Tracking transmission of apicomplexan symbionts in diverse Caribbean corals. PLoS ONE 8, e80618 (2013).

Baird, A. H., Guest, J. R. & Willis, B. L. Systematic and biogeographical patterns in the reproductive biology of scleractinian corals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40, 551–571 (2009).

Quigley, K. M., Willis, B. L. & Bay, L. K. Heritability of the Symbiodinium community in vertically- and horizontally-transmitting broadcast spawning corals. Sci. Rep. 7, 8219 (2017).

Meyer, J. L., Paul, V. J. & Teplitski, M. Community shifts in the surface microbiomes of the coral Porites astreoides with unusual lesions. PLoS ONE 9, e100316 (2014).

Glasl, B., Herndl, G. J. & Frade, P. R. The microbiome of coral surface mucus has a key role in mediating holobiont health and survival upon disturbance. ISME J. 10, 2280–2292 (2016).

Davy, S. K., Allemand, D. & Weis, V. M. Cell biology of cnidarian–dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 229–261 (2012).

Kirk, N. L., Thornhill, D. J., Kemp, D. W., Fitt, W. K. & Santos, S. R. Ubiquitous associations and a peak fall prevalence between apicomplexan symbionts and reef corals in Florida and the Bahamas. Coral Reefs 32, 847–858 (2013).

Bröcker, M. J. et al. Crystal structure of the nitrogenase-like dark operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase catalytic complex (ChlN/ChlB)2. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27336–27345 (2010).

Comeau, A. M., Li, W. K. W., Tremblay, J.-É., Carmack, E. C. & Lovejoy, C. Arctic Ocean microbial community structure before and after the 2007 record sea ice minimum. PLoS ONE 6, e27492 (2011).

Bower, S. M. et al. Preferential PCR amplification of parasitic protistan small subunit rDNA from metazoan tissues. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 51, 325–332 (2004).

del Campo, J. et al. A universal set of primers to study animal associated microeukaryotic communities. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/485532v1 (2018).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

del Campo, J., Pombert, J. F., Šlapeta, J., Larkum, A. & Keeling, P. J. The ‘other’ coral symbiont: Ostreobium diversity and distribution. ISME J. 11, 296–299 (2017).

Huse, S. M. et al. VAMPS: a website for visualization and analysis of microbial population structures. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 41 (2014).

Massana, R. et al. Marine protist diversity in European coastal waters and sediments as revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 4035–4049 (2015).

de Vargas, C. et al. Eukaryotic plankton diversity in the sunlit ocean. Science 348, 1261605 (2015).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Flegontov, P. et al. Divergent mitochondrial respiratory chains in phototrophic relatives of apicomplexan parasites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 1115–1131 (2015).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5, e9490 (2010).

Li, D. et al. MEGAHIT v1.0: A fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods 102, 3–11 (2016).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Pruesse, E., Peplies, J. & Glöckner, F. O. SINA: accurate high-throughput multiple sequence alignment of ribosomal RNA genes. Bioinformatics 28, 1823–1829 (2012).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Kayal, E., Roure, B., Philippe, H., Collins, A. G. & Lavrov, D. V. Cnidarian phylogenetic relationships as revealed by mitogenomics. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 5 (2013).

Zapata, F. et al. Phylogenomic analyses support traditional relationships within Cnidaria. PLoS ONE 10, e0139068 (2015).

Kayal, E. et al. Phylogenomics provides a robust topology of the major cnidarian lineages and insights on the origins of key organismal traits. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 68 (2018).

Simpson, C., Kiessling, W., Mewis, H., Baron-Szabo, R. C. & Müller, J. Evolutionary diversification of reef corals: a comparison of the molecular and fossil records. Evolution 65, 3274–3284 (2011).

Stolarski, J. et al. The ancient evolutionary origins of Scleractinia revealed by azooxanthellate corals. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 316 (2011).

Park, E. et al. Estimation of divergence times in cnidarian evolution based on mitochondrial protein-coding genes and the fossil record. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 62, 329–345 (2012).

Baliński, A., Sun, Y. & Dzik, J. 470-million-year-old black corals from China. Naturwissenschaften 99, 645–653 (2012).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Zhang, Z. et al. KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 4, 259–263 (2006).

Kořený, L., Sobotka, R., Janouskovec, J., Keeling, P. J. & Oborník, M. Tetrapyrrole synthesis of photosynthetic chromerids is likely homologous to the unusual pathway of apicomplexan parasites. Plant Cell 23, 3454–3462 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Zwimpfer and B. Ross for assistance with sample processing and electron microscopy. This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research grant MOP-42517 (to P.J.K.), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Fellowship PDF-502457-2017 and a Killam Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (to W.K.K.) and the Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship FP7-PEOPLE-2012-IOF - 331450 CAARL and a Tula Foundation grant to the Centre for Microbial Biodiversity and Evolution (to J.d.C.).

Reviewer information

Nature thanks Christopher Howe, Patrick Wincker and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.K.K., J.d.C. and P.J.K. designed the study. W.K.K., J.d.C., M.J.A.V. and P.J.K. obtained samples. J.d.C., V.M. and W.K.K. conducted microbial community analyses. W.K.K. performed all other analyses. W.K.K. and P.J.K. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Mitochondrial genomes of corallicolids.

Names denote the host coral from which the genomes were retrieved. The three mitochondria-encoded genes are shown in blue. Tick marks (moving clockwise) denote 1,000 bp. It is unclear whether the genomes are circular (as depicted), or tandem linear.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Distribution and diversity of corallicolid type-N from eukaryotic microbiome surveys.

a, Phylogenetic placement of short-amplicon OTUs (red) and near-full-length sequences (black), which show the diversity of the type-N clade. Coral host species are indicated. Values at nodes denote maximum likelihood bootstrap support (n = 1,000). Relationships between type-N lineages were generally poorly resolved. b, Presence of type-N reads in 18S rRNA gene surveys from environmental and host-associated samples, which shows that type-N is largely restricted to corals. Surveys included in this analysis are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Extended Data Fig. 3 No correlation of ARL-V community structure with abiotic factors.

a, Geographical location. b, Water depth. Correlation calculated using ANOSIM with 999 permutations. N/A, not available.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Transmission electron micrographs of darkly stained organelles in corallicolid cells, showing distinctive internal structures.

Structure and orientations (sagittal and transverse sections illustrated at the top) were inferred from viewing multiple organelles from several cells. Imaging was conducted in triplicate; representative results are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Tetrapyrrole and chlorophyll biosynthesis pathways, showing putative function of genes.

Genes retained in the corallicolid plastid genome (acsF, chlL, chlN and chlB) are highlighted. All enzymatic steps depicted here are inferred to occur within the apicomplexan plastid58.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Position of corallicolids in phylogenetic trees.

a, Phylogenetic placement of corallicolids, based on mitochondria-encoded proteins. b, Phylogenetic placement of corallicolids, based on plastid-encoded proteins. c, Phylogenetic placement of corallicolid chlorophyll biosynthesis proteins (concatenation of proteins ChlL, ChlN and ChlB on the left; AcsF on the right). All phylogenetic trees shown were produced with the maximum likelihood algorithm; values at nodes denote maximum likelihood bootstrap support percentages (n = 1,000 replicates) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (see Methods).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Conservation of key amino acid residues implies conservation of protein function in chlorophyll biosynthesis genes.

a, b, Sequence alignment of AcsF (a) and ChlN (b) proteins. For ChlN alignment, a comparison to NifD is shown. ‘Corallicolid meta’ sequence is derived from metagenomics and metatranscriptomics assembly; ‘Corallicolid wkC1’ is from the complete plastid sequence.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Phylogenetic placement of corallicolids, based on putative nucleus-encoded proteins.

Based on concatenation of HSP90, RPL3, RPL27A, RPS8, RPS19, RPS21 and RPS27 proteins (Supplementary Table 6). The tree shown was produced with the maximum likelihood algorithm; values at nodes denote maximum likelihood bootstrap support percentages (n = 1,000 replicates) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (see Methods).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Corallicolid phylogenetic placement using plastid data shows ambiguity.

a, Pairwise amino acid identities and dN values support a close relationship between corallicolids and the Coccidia. b, Phylogenetic analysis of single plastid genes and proteins to test alternative topologies of corallicolid placement. Results vary by gene and methodology: although most plastid genes show a basal placement for corallicolids, a few support the grouping of corallicolids within the Apicomplexa. Tree construction methods are indicated at top, with the model of evolution in parentheses. NJ, neighbour joining; MP, maximum parsimony; ML, maximum likelihood. A dash indicates a lack of support for either topology. N/A, not applicable.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 1: Coral samples used in this study. Includes data on wild coral samples and aquarium coral samples.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 2: Eukaryote and prokaryote OTU tables and representative sequences, generated from this study. Includes data on 18S rRNA gene read abundances, 16S rRNA gene read abundances, assigned taxonomic identity of OTUs and representative sequences.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 3: Summary of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic dataset survey results, with list of contigs corresponding to the corallicolid plastid genome.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 4: Corallicolid prevalence from previous studies. Includes list of host coral species, dates and locations.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 5: Sources and statistics of 18S rRNA gene amplicon datasets used for analysis of type-N distribution. Includes OTU tables and representative sequences from these data.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 6: List of hits for potential nuclear-encoded corallicolid genes, and photosystem genes.

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 7: Nucleotide sequences used in this study (accession numbers).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwong, W.K., del Campo, J., Mathur, V. et al. A widespread coral-infecting apicomplexan with chlorophyll biosynthesis genes. Nature 568, 103–107 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1072-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1072-z

This article is cited by

-

The coral microbiome in sickness, in health and in a changing world

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2024)

-

Integrating cryptic diversity into coral evolution, symbiosis and conservation

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

Patterns of host-parasite associations between marine meiofaunal flatworms (Platyhelminthes) and rhytidocystids (Apicomplexa)

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Beyond the Symbiodiniaceae: diversity and role of microeukaryotic coral symbionts

Coral Reefs (2023)

-

From polyps to pixels: understanding coral reef resilience to local and global change across scales

Landscape Ecology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.