Abstract

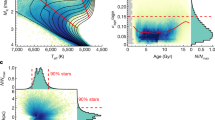

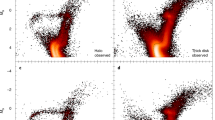

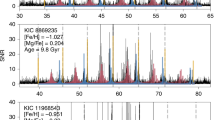

The assembly of our Galaxy can be reconstructed using the motions and chemistry of individual stars1,2. Chemo-dynamical studies of the stellar halo near the Sun have indicated the presence of multiple components3, such as streams4 and clumps5, as well as correlations between the stars’ chemical abundances and orbital parameters6–8. Recently, analyses of two large stellar surveys9,10 revealed the presence of a well populated elemental abundance sequence7,11, two distinct sequences in the colour–magnitude diagram12 and a prominent, slightly retrograde kinematic structure13,14 in the halo near the Sun, which may trace an important accretion event experienced by the Galaxy15. However, the link between these observations and their implications for Galactic history is not well understood. Here we report an analysis of the kinematics, chemistry, age and spatial distribution of stars that are mainly linked to two major Galactic components: the thick disk and the stellar halo. We demonstrate that the inner halo is dominated by debris from an object that at infall was slightly more massive than the Small Magellanic Cloud, and which we refer to as Gaia–Enceladus. The stars that originate in Gaia–Enceladus cover nearly the full sky, and their motions reveal the presence of streams and slightly retrograde and elongated trajectories. With an estimated mass ratio of four to one, the merger of the Milky Way with Gaia–Enceladus must have led to the dynamical heating of the precursor of the Galactic thick disk, thus contributing to the formation of this component approximately ten billion years ago. These findings are in line with the results of galaxy formation simulations, which predict that the inner stellar halo should be dominated by debris from only a few massive progenitors2,16.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data generated and analysed in this study are provided as Source Data or Supplementary Data.

References

Freeman, K. & Bland-Hawthorn, J. The new Galaxy: signatures of its formation. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 40, 487–537 (2002).

Helmi, A., White, S. D. M. & Springel, V. The phase-space structure of cold dark matter haloes: insights into the Galactic halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 339, 834–848 (2003).

Carollo, D. et al. Two stellar components in the halo of the Milky Way. Nature 450, 1020–1025 (2007); erratum 451, 216 (2008).

Helmi, A., White, S. D. M., de Zeeuw, P. T. & Zhao, H. Debris streams in the solar neighbourhood as relicts from the formation of the Milky Way. Nature 402, 53–55 (1999).

Morrison, H. L. et al. Fashionably late? Building up the Milky Way’s inner halo. Astrophys. J. 694, 130–143 (2009).

Chiba, M. & Beers, T. C. Kinematics of metal-poor stars in the Galaxy. III. Formation of the stellar halo and thick disk as revealed from a large sample of non-kinematically selected stars. Astron. J. 119, 2843–2865 (2000).

Nissen, P. E. & Schuster, W. J. Two distinct halo populations in the solar neighbourhood – evidence from stellar abundance ratios and kinematics. Astron. Astrophys. 511, L10 (2010).

Beers, T. C. et al. Bright metal-poor stars from the Hamburg/ESO survey. II. A chemodynamical analysis. Astrophys. J. 835, 81 (2017).

Abolfathi, B. et al. The fourteenth data release of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey: first spectroscopic data from the extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey and from the second phase of the Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 235, 42 (2018).

Gaia Collaboration. The Gaia mission. Astron. Astrophys. 595, A1 (2016).

Hayes, C. R. et al. Disentangling the Galactic halo with APOGEE. I. Chemical and kinematical investigation of distinct metal-poor populations. Astrophys. J. 852, 49 (2018).

Gaia Collaboration. Gaia Data Release 2: observational Hertzsprung– Russell diagrams. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A10 (2018).

Belokurov, V., Erkal, D., Evans, N. W., Koposov, S. E. & Deason, A. J. Co-formation of the Galactic disc and the stellar halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 478, 611–619 (2018).

Koppelman, H. H., Helmi, A. & Veljanoski, J. One large blob and many streams frosting the nearby stellar halo in Gaia DR2. Astrophys. J. 860, L11 (2018).

Haywood, M. et al. In disguise or out of reach: first clues about in-situ and accreted stars in the stellar halo of the Milky Way from Gaia DR2. Astrophys. J. 863, 113 (2018).

Cooper, A. P. et al. Galactic stellar haloes in the CDM model. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 406, 744–766 (2010).

Gaia Collaboration. Gaia Data Release 2. Summary of the contents and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A1 (2018).

Villalobos, A. & Helmi, A. Simulations of minor mergers – I. General properties of thick discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 391, 1806–1827 (2008).

Nissen, P. E. & Schuster, W. J. Two distinct halo populations in the solar neighborhood. II. Evidence from stellar abundances of Mn, Cu, Zn, Y, and Ba. Astron. Astrophys. 530, A15 (2011).

Fernández-Alvar, E. et al. Disentangling the Galactic halo with APOGEE. II. Chemical and star formation histories for the two distinct populations. Astrophys. J. 852, 50 (2018).

Helmi, A. The stellar halo of the Galaxy. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 15, 145–188 (2008).

Van der Marel, R. P., Kallivayalil, N. & Besla, G. Kinematical structure of the Magellanic System. Proc. IAU 256, 81–92 (2008).

Marigo, P. et al. A new generation of PARSEC-COLIBRI stellar isochrones including the TP-AGB phase. Astrophys. J. 835, 77 (2017).

Schuster, W. J., Moreno, E., Nissen, P. E. & Pichardo, B. Two distinct halo populations in the solar neighborhood. III. Evidence from stellar ages and orbital parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 538, A21 (2012).

Hawkins, K., Jofré, P., Gilmore, G. & Masseron, T. On the relative ages of the α-rich and α-poor stellar populations in the Galactic halo. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 445, 2575–2588 (2014).

Clementini, G. et al. Gaia Data Release 2: specific characterisation and validation of all-sky Cepheids and RR Lyrae stars. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.02079 (2018).

Gaia Collaboration. Gaia Data Release 2: kinematics of globular clusters and dwarf galaxies around the Milky Way. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A12 (2018).

VandenBerg, D. A., Brogaard, K., Leaman, R. & Casagrande, L. The ages of 55 globular clusters as determined using an improved \({\rm{\Delta }}{V}_{{\rm{TO}}}^{{\rm{HB}}}\) method along with color–magnitude diagram constraints, and their implications for broader issues. Astrophys. J. 775, 134 (2013).

McMillan, P. J. The mass distribution and gravitational potential of the Milky Way. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 465, 76–94 (2017).

Behroozi, P. S., Wechsler, R. H. & Conroy, C. The average star formation histories of galaxies in dark matter halos from z = 0–8. Astrophys. J. 770, 57 (2013).

Schönrich, R., Binney, J. & Dehnen, W. Local kinematics and the local standard of rest. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 403, 1829–1833 (2010).

Gaia Collaboration. Gaia Data Release 2: mapping the Milky Way disc kinematics. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A11 (2018).

Helmi, A., Veljanoski, J., Breddels, M. A., Tian, H. & Sales, L. V. A box full of chocolates: the rich structure of the nearby stellar halo revealed by Gaia and RAVE. Astron. Astrophys. 598, A58 (2017).

Arenou, F. et al. Gaia Data Release 2: catalogue validation. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A17 (2018).

Jean-Baptiste, I. et al. On the kinematic detection of accreted streams in the Gaia era: a cautionary tale. Astron. Astrophys. 604, A106 (2017).

Villalobos, A. & Helmi, A. Simulations of minor mergers – II. The phase-space structure of thick discs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 399, 166–176 (2009).

Morrison, H. L., Flynn, C. & Freeman, K. C. Where does the disk stop and the halo begin? Kinematics in a rotation field. Astron. J. 100, 1191–1222 (1990).

Majewski, S. R. et al. The Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE). Astron. J. 154, 94 (2017).

García Pérez, A. E. et al. ASPCAP: the APOGEE stellar parameter and chemical abundances pipeline. Astron. J. 151, 144 (2016).

Lindegren, L. et al. Gaia Data Release 2: the astrometric solution. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A2 (2018).

Butkevich, A. G., Klioner, S. A., Lindegren, L., Hobbs, D. & van Leeuwen, F. Impact of basic angle variations on the parallax zero point for a scanning astrometric satellite. Astron. Astrophys. 603, A45 (2017).

Robin, A. C. et al. Gaia Universe model snapshot. A statistical analysis of the expected contents of the Gaia catalogue. Astron. Astrophys. 543, A100 (2012).

Posti, L., Helmi, A., Veljanoski, J. & Breddels, M. The dynamically selected stellar halo of the Galaxy with Gaia and the tilt of the velocity ellipsoid. Astron. Astrophys. 615, A70 (2018).

Carollo, D., Martell, S. L., Beers, T. C. & Freeman, K. C. CN anomalies in the halo system and the origin of globular clusters in the Milky Way. Astrophys. J. 769, 87 (2013).

Brook, C. B., Kawata, D., Gibson, B. K. & Flynn, C. Galactic halo stars in phase space: a hint of satellite accretion? Astrophys. J. 585, L125–L129 (2003).

Gaia Collaboration. Gaia Data Release 1. Summary of the astrometric, photometric, and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 595, A2 (2016).

Bonaca, A., Conroy, C., Wetzel, A., Hopkins, P. F. & Kereš, D. Gaia reveals a metal-rich, in situ component of the local stellar halo. Astrophys. J. 845, 101 (2017).

Deason, A. J., Belokurov, V., Koposov, S. E. & Lancaster, L. Apocenter pile-up: origin of the stellar halo density break. Astrophys. J. 862, L1 (2018).

Conroy, C. et al. They might be giants: an efficient color-based selection of red giant stars. Astrophys. J. 861, L16 (2018).

Belokurov, V. et al. The Hercules–Aquila cloud. Astrophys. J. 657, L89–L92 (2007).

Larsen, J. A., Cabanela, J. E. & Humphreys, R. M. Mapping the asymmetric thick disk. II. Distance, size, and mass of the Hercules thick disk cloud. Astron. J. 141, 130 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Á. Villalobos for permission to use his suite of simulations, and to M. Breddels for the software package Vaex (http://vaex.astro.rug.nl), which was used for part of our analyses. We thank H.-W. Rix, D. Hogg and A. Price-Whelan for comments. We have made use of data from the European Space Agency mission Gaia (http://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC; see http://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dpac/consortium). Funding for DPAC has been provided by national institutions, in particular the institutions participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement. We also used data from the APOGEE survey— a part of Sloan Digital Sky Survey IV, which is managed by the Astrophysical Research Consortium for the Participating Institutions of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) Collaboration (http://www.sdss.org). A.H., H.H.K., D.M. and J.V. acknowledge financial support from a Vici grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and A.G.A.B. from the Netherlands Research School for Astronomy (NOVA).

Reviewer information

Nature thanks T. C. Beers, K. V. Johnston and K. Venn for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the work. A.H. led and contributed to all aspects of the analysis and wrote the manuscript. C.B. compiled the APOGEE data, provided the cross-match to the Gaia data, was involved in the chemical abundance analysis and, together with D.M., analysed the HRD. H.H.K. and J.V. carried out the dynamical analysis and identification of member stars. A.G.A.B. proposed the preparation of this paper, explored the impact of the selection effects and contributed to the writing of the paper, together with the other co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Slices of phase space used to isolate Gaia–Enceladus stars.

a, Energy E versus angular momentum Lz for stars in the 6D Gaia dataset that satisfy the quality criteria described in the text, with ϖ > 0.2 mas (5 kpc from the Sun) and |V − VLSR| > 210 km s−1. The dashed lines indicate the criteria used to select Gaia–Enceladus stars, namely, −1,500 kpc km s−1 < Lz < 150 kpc km s−1 and E > −1.8 × 105 km2 s−2. These criteria follow roughly the structure’s shape (for comparison, see Extended Data Fig. 3b) but are slightly conservative for the upper limit of Lz to prevent too much contamination by the thick disk. However, small shifts—such as those obtained by considering an upper limit of 250 kpc km s−1 or a lower limit of −750 kpc km s−1 for Lz, or E > −2 × 105 km2 s−2—do not result in drastic changes to the results presented in the paper. The colour scale indicates the logarithm of the counts in the bins, with red corresponding to the highest number of counts, yellow and blue to 1/6th and 1/30th of this value, respectively, and purple to empty bins. b, Angular momentum Lz versus the Galactocentric distance R for all stars in the 6D Gaia with ϖ > 0.2 mas. The black points are the halo-star sample shown in a. c, Same as b, but for star particles in the merger simulation18 shown in Fig. 1b. Blue points correspond to stars from the satellite and grey points to the host disk, and the positions and velocities have been scaled as described in the text. In this figure, E, Lz and R have been scaled by the energy (Esun = −1.63 × 105 km2 s−2 in the Galactic potential used), angular momentum (Lz,sun = 1,902.4 kpc km s−1) and Galactocentric distance (Rsun = 8.2 kpc) of the Sun, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Effect of a zero-point offset in the parallax on Lz.

a, Distribution of the difference between the initial (Lz(init)) and ‘measured’ (Lz(obs); after error convolution) z-angular momentum for stars from the GUMS model with ‘measured’ distances between 5 and 10 kpc and with galactic longitude l = (−60°, −20°). b, Mean value of the difference over the full sky.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Dynamical properties of stars for a smooth dataset.

a, b, Velocity (a) and E–Lz (b) distribution, for a dataset obtained by reshuffling the velocities of the stars plotted in Fig. 1a and in Extended Data Fig. 1a, respectively. Visual comparison to those figures shows that these random sets are less clumped than the observed distributions of the Gaia halo stars. Lz and E in b are scaled as in Extended Data Fig. 1, and the colour scale indicates the logarithm of the counts in the bins, with dark red corresponding to the highest number of counts, yellow and blue to 1/5th and 1/15th of this value, respectively, and purple to empty bins.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Distribution of angles between proper-motion vectors for neighbouring stars in the sky.

The blue and red histograms correspond to Gaia–Enceladus stars and a mock dataset, respectively. This mock dataset uses the positions of the stars in Gaia–Enceladus, but velocities generated randomly according to a multivariate Gaussian distribution43; only velocities that satisfy −1,500 kpc km s−1 < Lz < 150 kpc km s−1 are kept in the mock dataset, as in the real data. For each star, we find its nearest neighbour in the sky and then determine the angle ∆θ between their proper-motion vectors for the data and for the mock dataset. We then count the number of such pairs with a given angle ∆θ.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data

This file contains source data for figure 1a.

Supplementary Data

This file contains source data for figure 1b.

Supplementary Data

This file contains source data for figures 2a and b.

Supplementary Data

This file contains source data for figure 2c.

Supplementary Data

This file contains source data for figures 3 and 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Helmi, A., Babusiaux, C., Koppelman, H.H. et al. The merger that led to the formation of the Milky Way’s inner stellar halo and thick disk. Nature 563, 85–88 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0625-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0625-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A tilted dark halo origin of the Galactic disk warp and flare

Nature Astronomy (2023)

-

The first comprehensive Milky Way stellar mock catalogue for the Chinese Space Station Telescope Survey Camera

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

-

Detecting weak beryllium lines with CUBES

Experimental Astronomy (2023)

-

Dark matter substructures affect dark matter-electron scattering in xenon-based direct detection experiments

Journal of High Energy Physics (2023)

-

Chemical and stellar properties of early-type dwarf galaxies around the Milky Way

Nature Astronomy (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.