Abstract

Roots are one of the three fundamental organ systems of vascular plants1, and have roles in anchorage, symbiosis, and nutrient and water uptake2,3,4. However, the fragmentary nature of the fossil record obscures the origins of roots and makes it difficult to identify when the sole defining characteristic of extant roots—the presence of self-renewing structures called root meristems that are covered by a root cap at their apex1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9—evolved. Here we report the discovery of what are—to our knowledge—the oldest meristems of rooting axes, found in the earliest-preserved terrestrial ecosystem10 (the 407-million-year-old Rhynie chert). These meristems, which belonged to the lycopsid Asteroxylon mackiei11,12,13,14, lacked root caps and instead developed a continuous epidermis over the surface of the meristem. The rooting axes and meristems of A. mackiei are unique among vascular plants. These data support the hypothesis that roots, as defined in extant vascular plants by the presence of a root cap7, were a late innovation in the vascular lineage. Roots therefore acquired traits in a stepwise fashion. The relatively late origin in lycophytes of roots with caps is consistent with the hypothesis that roots evolved multiple times2 rather than having a single origin1, and the extensive similarities between lycophyte and euphyllophyte roots15,16,17,18 therefore represent examples of convergent evolution. The key phylogenetic position of A. mackiei—with its transitional rooting organ—between early diverging land plants that lacked roots and derived plants that developed roots demonstrates how roots were ‘assembled’ during the course of plant evolution.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schneider, H., Pryer, K. M., Cranfill, R., Smith, A. R. & Wolf, P. G. in Developmental Genetics and Plant Evolution (eds Cronk, Q. C. B. et al.) 330–364 (Taylor & Francis, London, 2002).

Raven, J. A. & Edwards, D. Roots: evolutionary origins and biogeochemical significance. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 381–401 (2001).

Kenrick, P. & Strullu-Derrien, C. The origin and early evolution of roots. Plant Physiol. 166, 570–580 (2014).

Kenrick, P. in Plant Roots: The Hidden Half (eds Eshel, A. & Beeckamn, T.) 1–14 (Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, 2013).

Gensel, P. G., Kotyk, M. E. & Brasinger, J. F. in Plants Invade The Land: Evolutionary and Environmental Perspectives (eds Gensel, P. G. & Edwards, D.) 83–102 (Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 2001).

Matsunaga, K. K. S. & Tomescu, A. M. F. Root evolution at the base of the lycophyte clade: insights from an Early Devonian lycophyte. Ann. Bot. 117, 585–598 (2016).

Sachs, J. Text-book of Botany, Morphological and Physiological (translated and annotated by A. W. Bennett and W. T. Thiselton Dyer) (Clarendon, Oxford, 1875).

Hao, S., Xue, J., Guo, D. & Wang, D. Earliest rooting system and root:shoot ratio from a new Zosterophyllum plant. New Phytol. 185, 217–225 (2010).

Matsunaga, K. K. S. & Tomescu, A. M. F. An organismal concept for Sengelia radicans gen. et sp. nov. – morphology and natural history of an Early Devonian lycophyte. Ann. Bot. 119, 1097–1113 (2017).

Edwards, D., Kenrick, P. & Dolan, L. History and contemporary significance of the Rhynie cherts—our earliest preserved terrestrial ecosystem. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160489 (2018).

Edwards, D. Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyfield cherts. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 397–410 (2003).

Kidston, R. & Lang, W. H. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part III. Asteroxylon mackiei, Kidston and Lang. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 52, 643–680 (1920).

Kidston, R. & Lang, W. H. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part IV. Restorations of the vascular cryptogams, and discussion of their bearing on the general morphology of the Pteridophyta and the origin of the organisation of land plants. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 52, 831–854 (1921).

Kenrick, P. & Crane, P. R. The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants: A Cladistic Study (Smithsonian Series in Comparative Evolutionary Biology) (Smithsonian Institute, Washington DC, 1997).

Huang, L. & Schiefelbein, J. Conserved gene expression programs in developing roots from diverse plants. Plant Cell 27, 2119–2132 (2015).

Hetherington, A. J. & Dolan, L. The evolution of lycopsid rooting structures: conservatism and disparity. New Phytol. 215, 538–544 (2017).

Fujinami, R. et al. Root apical meristem diversity in extant lycophytes and implications for root origins. New Phytol. 215, 1210–1220 (2017).

Foster, A. S. & Gifford, E. M. Comparative Morphology of Vascular Plants (W. H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1959).

Bhutta, A. A. Studies on the Flora of the Rhynie Chert. PhD thesis, Univ. Wales, Cardiff (1969).

Kerp, H. Organs and tissues of Rhynie chert plants. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160495 (2018).

Kenrick, P. & Crane, P. R. Water-conducting cells in early fossil land plants: implications for the early evolution of tracheophytes. Bot. Gaz. 152, 335–356 (1991).

Strullu-Derrien, C., Wawrzyniak, Z., Goral, T. & Kenrick, P. Fungal colonization of the rooting system of the early land plant Asteroxylon mackiei from the 407-Myr-old Rhynie Chert (Scotland, UK). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 179, 201–213 (2015).

Clowes, F. A. L. Apical Meristems (Blackwell, Oxford, 1961).

Guttenberg, H. V. Histogenese der Pteridophyten. Handbuch der Pflanzenanatomie Vol. VII.2 (Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin, 1966).

Hueber, F. M. Thoughts on the early lycopsids and zosterophylls. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 79, 474–499 (1992).

Heimsch, C. & Seago, J. L. Jr. Organization of the root apical meristem in angiosperms. Am. J. Bot. 95, 1–21 (2008).

Kelman, R., Feist, M., Trewin, N. H. & Hass, H. Charophyte algae from the Rhynie chert. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 445–455 (2003).

Hetherington, A. J., Dubrovsky, J. G. & Dolan, L. Unique cellular organization in the oldest root meristem. Curr. Biol. 26, 1629–1633 (2016).

Strullu-Derrien, C., McLoughlin, S., Philippe, M., Mørk, A. & Strullu, D. G. Arthropod interactions with bennettitalean roots in a Triassic permineralized peat from Hopen, Svalbard Archipelago (Arctic). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 348–349, 45–58 (2012).

Shishkova, S., Rost, T. L. & Dubrovsky, J. G. Determinate root growth and meristem maintenance in angiosperms. Ann. Bot. 101, 319–340 (2008).

Brown, M. & Lowe, D. G. Automatic panoramic image stitching using invariant features. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 74, 59–73 (2007).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Barbier de Reuille, P. et al. MorphoGraphX: A platform for quantifying morphogenesis in 4D. eLife 4, 05864 (2015).

Garwood, R. & Dunlop, J. The walking dead: Blender as a tool for paleontologists with a case study on extinct arachnids. J. Paleontol. 88, 735–746 (2014).

Acknowledgements

A.J.H. was funded by the George Grosvenor Freeman Fellowship by Examination in Sciences, Magdalen College (Oxford). L.D. was funded by a European Research Council Advanced Grant (EVO500, contract 250284) and a European Commission Framework 7 Initial Training Network (PLANTORIGINS, project identifier 238640). We are grateful to the Oxford University Herbaria, the University of Manchester, Manchester Museum, The Hunterian, University of Glasgow and the London Natural History Museum for access to fossil thin sections, and to the curators of these collections (S. Harris, K. Sherburn, N. Clark and P. Hayes) for their assistance. We thank T. Goral, C. Strullu-Derrien, C. Kirchhelle, I. Moore and I. Rahmen for assistance and advice for confocal imaging, segmentation and 3D reconstructions; J. Baker for photographic advice; and A. M. Hetherington, N. J. Hetherington and members of the Dolan laboratory for helpful comments and discussions.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks P. Crane and P. Kenrick for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.H. and L.D. designed the project. A.J.H. carried out the analyses. A.J.H. and L.D. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Five root apices were found on three thin sections in which A. mackiei was the only plant species present.

a–c, Diagnostic features of A. mackiei include the apices of leafy shoots (black arrowhead, a), star-shaped xylem (black arrowhead, b) and leaves (black arrowhead, c). a, GLAHM Kid 3080. b, NHMUK V.15642. c, OXF 108. Scale bars, 1 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 A. mackiei rooting axes grew in the direction of the gravity vector.

a–c, Positively gravitropic growth of two apices (a) was inferred from their orientation relative to sediment layers in both the growth substrate (dark brown and black bands at base of b) and a geopetally infilled void (c) preserved in the thin section. The position of both the apices and geopetally infilled void are highlighted with black boxes within the thin section (b). a–c, NHMUK V.15642. Scale bars, 1 mm (a, c), 1 cm (b).

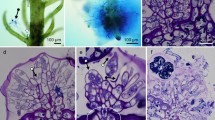

Extended Data Fig. 3 Fundamental tissues present in an apex of a rooting axis preserved after growth had finished, and a meristem of a rooting axis preserved during active growth.

a, b, Root apices with fundamental tissue types colour-coded. Blue, epidermis; pink, promeristem; orange, cortex; and green, procambium. c, d, Magnified images of the apical regions of a (c) and b (d). The presence of differentiated vascular tissue (arrowhead, c) close to the tip of the apex indicates that this apex was not active at the time of preservation. By contrast, in d there is no differentiated vascular tissue. Instead, the apex is characterized by large numbers of cells and cell size gradually increases with distance from the tip, which indicates that the apex was active when fossilized. a, c NHMUK V.15642 (same specimen as illustrated in Fig. 1a), b, c, OXF 108 (same specimen as illustrated in Figs. 1d, 2a, b). Scale bars, 500 μm (a), 250 μm (b), 150 μm (c), 100 μm (d).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Mulm coats the rooting axes and leafy shoots of A. mackiei.

a–d, A thin layer of degraded organic material called mulm27 (highlighted with arrowheads, a–d) coats both the rooting axes (a, c) and leafy shoots of A. mackiei. a, b, GLAHM Kid 3080. c, d, OXF 108. Scale bars, 500 μm (a, c, d), 1 mm (b).

Supplementary information

Video 1

Segmentation of the epidermal surface of an Asteroxylon mackiei rooting axis meristem. MorphoGraphX was used to segment the epidermal surface from a z-stack of images captured on a confocal microscope. GLAHM Kid 3080. Scale bar 50 µm.

Video 2

Asteroxylon mackiei rooting axis meristems were covered by a continuous layer of epidermis and lacked a root cap. Animation showing the three-dimensional model produced of the rooting axis meristem of A. mackiei segmented using MorphoGraphX and animated using BlenderTM. GLAHM Kid 3080. Scale bar 50 µm.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hetherington, A.J., Dolan, L. Stepwise and independent origins of roots among land plants. Nature 561, 235–238 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0445-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0445-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Composition of continental crust altered by the emergence of land plants

Nature Geoscience (2022)

-

The origin of a land flora

Nature Plants (2022)

-

Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals conserved programmes underpinning organogenesis and reproduction in land plants

Nature Plants (2021)

-

Multiple origins of dichotomous and lateral branching during root evolution

Nature Plants (2020)

-

Root apical meristem diversity and the origin of roots: insights from extant lycophytes

Journal of Plant Research (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.