Abstract

The work of Berezinskii, Kosterlitz and Thouless in the 1970s1,2 revealed exotic phases of matter governed by the topological properties of low-dimensional materials such as thin films of superfluids and superconductors. A hallmark of this phenomenon is the appearance and interaction of vortices and antivortices in an angular degree of freedom—typified by the classical XY model—owing to thermal fluctuations. In the two-dimensional Ising model this angular degree of freedom is absent in the classical case, but with the addition of a transverse field it can emerge from the interplay between frustration and quantum fluctuations. Consequently, a Kosterlitz–Thouless phase transition has been predicted in the quantum system—the two-dimensional transverse-field Ising model—by theory and simulation3,4,5. Here we demonstrate a large-scale quantum simulation of this phenomenon in a network of 1,800 in situ programmable superconducting niobium flux qubits whose pairwise couplings are arranged in a fully frustrated square-octagonal lattice. Essential to the critical behaviour, we observe the emergence of a complex order parameter with continuous rotational symmetry, and the onset of quasi-long-range order as the system approaches a critical temperature. We describe and use a simple approach to statistical estimation with an annealing-based quantum processor that performs Monte Carlo sampling in a chain of reverse quantum annealing protocols. Observations are consistent with classical simulations across a range of Hamiltonian parameters. We anticipate that our approach of using a quantum processor as a programmable magnetic lattice will find widespread use in the simulation and development of exotic materials.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Berezinskii, V. L. Destruction of long-range order in one-dimensional and two-dimensional systems having a continous symmetry group II: quantum systems. Sov. Phys. JETP 34, 610–616 (1972).

Kosterlitz, J. M. & Thouless, D. J. Ordering, metastability and phase transitions in two-dimensional systems. J. Phys. C 6, 1181–1203 (1973).

Moessner, R., Sondhi, S. L. & Chandra, P. Two-dimensional periodic frustrated Ising models in a transverse field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4457–4460 (2000).

Moessner, R. & Sondhi, S. L. Ising models of quantum frustration. Phys. Rev. B 63, 224401 (2001).

Isakov, S. V. & Moessner, R. Interplay of quantum and thermal fluctuations in a frustrated magnet. Phys. Rev. B 68, 104409 (2003).

Feynman, R. P. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073–1078 (1996).

Gross, C. & Bloch, I. Quantum simulations with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Science 357, 995–1001 (2017).

Paraoanu, G. S. Recent progress in quantum simulation using superconducting circuits. J. Low Temp. Phys. 175, 633–654 (2014).

Hadzibabic, Z., Krüger, P., Cheneau, M., Battelier, B. & Dalibard, J. Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless crossover in a trapped atomic gas. Nature 441, 1118–1121 (2006).

Zhang, J. et al. Observation of a many-body dynamical phase transition with a 53-qubit quantum simulator. Nature 551, 601–604 (2017).

Hensgens, T. et al. Quantum simulation of a Fermi–Hubbard model using a semiconductor quantum dot array. Nature 548, 70–73 (2017).

Georgescu, I. M., Ashhab, S. & Nori, F. Quantum simulation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 153–185 (2014).

Mohseni, M. et al. Commercialize quantum technologies in five years. Nature 543, 171–175 (2017).

Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.00862 (2018).

Johnson, M. W. et al. Quantum annealing with manufactured spins. Nature 473, 194–198 (2011).

Harris, R. et al. Experimental investigation of an eight-qubit unit cell in a superconducting optimization processor. Phys. Rev. B 82, 024511 (2010).

Bunyk, P. I. et al. Architectural considerations in the design of a superconducting quantum annealing processor. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 24, 1–10 (2014).

Mott, A., Job, J., Vlimant, J.-r., Lidar, D. & Spiropulu, M. Solving a Higgs optimization problem with quantum annealing for machine learning. Nature 550, 375–379 (2017).

Amin, M. H., Andriyash, E., Rolfe, J., Kulchytskyy, B. & Melko, R. Quantum Boltzmann machine. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021050 (2018).

Moessner, R. & Ramirez, A. P. Geometrical frustration. Phys. Today 59, 24–29 (2006).

Kosterlitz, J. M. & Thouless, D. J. Early work on defect driven phase transitions. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 30, 1630018 (2016).

Han, Z. et al. Collapse of superconductivity in a hybrid tin-graphene Josephson junction array. Nat. Phys. 10, 380–386 (2014).

Jiang, Y. & Emig, T. Ordering of geometrically frustrated classical and quantum triangular Ising magnets. Phys. Rev. B 73, 104452 (2006).

Wang, Y.-C., Qi, Y., Chen, S. & Meng, Z. Y. Caution on emergent continuous symmetry: a Monte Carlo investigation of the transverse-field frustrated Ising model on the triangular and honeycomb lattices. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115160 (2017).

Blankschtein, D., Ma, M., Berker, A. N., Grest, G. S. & Soukoulis, C. M. Orderings of a stacked frustrated triangular system in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 29, 5250–5252 (1984).

José, J. V., Kadanoff, L. P., Kirkpatrick, S. & Nelson, D. R. Renormalization, vortices, and symmetry-breaking perturbations in the two-dimensional planar model. Phys. Rev. B 16, 1217–1241 (1977).

Lanting, T., King, A. D., Evert, B. & Hoskinson, E. Experimental demonstration of perturbative anticrossing mitigation using nonuniform driver Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. A 96, 042322 (2017).

Herbut, I. A Modern Approach to Critical Phenomena (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2007).

Chancellor, N. Modernizing quantum annealing using local searches. New J. Phys. 19, 023024 (2017).

Babbush, R., Love, P. J. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Adiabatic quantum simulation of quantum chemistry. Sci. Rep. 4, 6603 (2014).

Nishimori, H. & Takada, K. Exponential enhancement of the efficiency of quantum annealing by non-stochastic Hamiltonians. Front. ICT 4, 1–11 (2017).

Korshunov, S. E. Finite-temperature phase transitions in the quantum fully frustrated transverse-field Ising models. Phys. Rev. B 86, 014429 (2012).

Rieger, H. & Kawashima, N. Application of a continuous time cluster algorithm to the two-dimensional random quantum Ising ferromagnet. Eur. Phys. J. B 9, 233–236 (1999).

Swendsen, R. H. & Wang, J.-S. Replica Monte Carlo simulation of spin-glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2607–2609 (1986).

Andriyash, E. & Amin, M. H. Can quantum Monte Carlo simulate quantum annealing? Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.09277 (2017).

Guo, M., Bhatt, R. N. & Huse, D. A. Quantum critical behavior of a three-dimensional Ising spin glass in a transverse magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 4137–4140 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Affleck, S. Boixo, E. Farhi, M. Franz, I. Herbut, S. Isakov, S. Lloyd, R. Melko, M. Mohseni, H. Neven and Y. Wan for discussions. We are grateful to the research, engineering and operations staff at D-Wave Systems for directly and indirectly supporting this research.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks A. Kerman, M. Troyer and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D.K., J.C., J.R., I.O., E.A. and M.H.A. conceived and designed the experiment. J.R., E.A., I.O. and A.D.K. conducted classical simulations. A.D.K. and I.O. conducted the main QA experiments. A.B. and M.R. calibrated the QA processor. T.L., R.H., K.B., A.F., G.P.-L., A.Y.S., K.B. and A.F. conducted supporting experiments and theoretical analysis. A.B., M.R., T.L., R.H., C.R., F.A., P.I.B., T.O., J.Y., C.E., N.L., J.W., L.J.S., E.H., Y.S., M.H.V., E.L., M.W.J. and J.H. designed, developed and fabricated the QA apparatus. M.H.A., A.D.K., J.C., J.R., I.O., E.A., T.L., R.H. and A.Y.S. contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are current or recent employees of D-Wave Systems Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Topological features in the two-dimensional XY model.

a, The ground state, in which all rotors have equal angle θ, has continuous U(1) symmetry, as a universal rotation of θ will not change the energy of the system. b, c, A vortex or antivortex (b and c, respectively) is a point around which the angle winds (rotates completely) clockwise or anticlockwise, respectively, when traversing a closed loop around the point in a clockwise direction. Both the energy and the entropy of an isolated vortex or antivortex region of radius R are proportional to log(R/r), where r is the lattice spacing.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Floppy spin aligns with the transverse field.

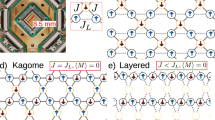

a, b, Two of six degenerate classical ground states differ by a flip of spin 1. c, With the addition of a perturbative transverse field Γ, spin 1 aligns with the transverse field in a symmetric superposition \(|\to \rangle =(|\uparrow \rangle +|\downarrow \rangle )/\sqrt{2}\), reducing the energy from −J to −J − Γ. Red and blue represent spin-up and spin-down, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Pseudospins from classical and quantum states.

a, Each pseudospin ψj is determined as a linear combination of basis vectors with weights given by σz operators. b, c, the pseudospin of the clock state \(\left|\to \uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle \) is eiπ/2. d, The six-fold-degenerate perturbative quantum ground states (white, with magnitude 1) and six-fold-degenerate classical ground states (black, with magnitude \(2/\sqrt{3}\)) admit twelve ‘clock’ pseudospins in the complex plane. Also shown are the classical excited states \(\left|\uparrow \uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle \) and \(\left|\downarrow \downarrow \downarrow \right\rangle \), which have pseudospin 0 and therefore correspond to a vortex or antivortex.

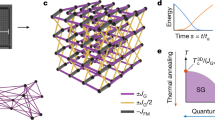

Extended Data Fig. 4 Annealing schedule and protocols.

a, Unitless energy scales for transverse field Γ and Ising couplings J as a function of annealing parameter s, compared with temperature T = 8.4 mK (the inset is a detail of the region studied: 0.2 ≤ s ≤ 0.3). b, Standard 16-μs forward anneal protocol given as s(t), which increases linearly from 0 to 1. c, 16-μs evolution in a reverse annealing protocol, where s drops from 1 to s = 0.3 over 3.5 μs, dwells at s for 16 μs, and quenches to 1 over 1 μs. Experiments, with the exception of relaxation time measurements, are performed with 216 μs (65 ms) dwells at target model s. d, The first eigengap E1 − E0 for a chain of four FM-coupled SQUIDs given by a physically realistic 8-level SQUID model deviates from the gap given by the desired 2-level SQUID model of Ising spins. e, To compensate for this deviation, we determine a nonlinear shift in s so that the gap of the chain of 8-level SQUIDS at s matches the gap of the chain of 2-level SQUIDs at f(s). This shift in s is roughly 0.03 to 0.05 in the region of interest, and is reflected in the effective schedule (a). f, To evaluate this compensation more generally, we place a flux bias on the first device of the chain and compare the eigenspectra of the 8-level SQUID model at s with the compensated 2-level SQUID model at f(s), for three values of s. Agreement in the first eigengap is good across a range of biases and s values.

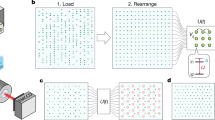

Extended Data Fig. 5 Convergence of quantum evolution Monte Carlo.

Our quantum evolution Monte Carlo sampling approach involves making a chain of 50 reverse annealing evolutions starting from an ordered state and a random state. At 8.4 mK, cooling of around 0.1 mK is observed during the first 25 evolutions. This cooling lowers m at s = 0.26, as the lower temperature slows evolution during the 1-μs quench. The same cooling increases the order parameter at s = 0.26, where the lower temperature results in evolution of a more ordered model. Shown are experimental results for increasing values of s (top row) and for s = 0.26 at increasing temperatures (bottom row). At s = 0.30, T = 8.4 mK, evolution is slow and the estimates of \(\left\langle m\right\rangle \) are far from the equilibrium value of \(\left\langle m\right\rangle \) after a single 65-ms evolution. Spin-bath polarization, which biases the estimators towards the initial condition at low temperatures, disappears as temperature is increased.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Embedding a cylindrical lattice into the qubit connectivity graph.

a, b, The cylindrical square-octagonal lattice with length L = 6 (a) is embedded into a region of the Chimera qubit connectivity graph (b). The embedding consists of two square sheets that are coupled together at the top and bottom. The largest instance studied with L = 15 uses 1,800 of the 2,048 qubits in the processor, with unused qubits along the outside boundary of the processor. FM couplers are in blue and AFM couplers are in red.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Effect of calibration refinement.

a, b, Symmetries in the lattice dictate that each qubit should have an average magnetization of zero (a) and that each AFM coupler should be frustrated with the same probability as other couplers in its rotational symmetry equivalence class of 2L couplers (b). We use a gradient-descent shim method (code available from the corresponding author on reasonable request) to maintain degeneracy among qubits and equivalent couplers with flux offsets and small adjustments to specified coupling energies. Data are taken for L = 15, with 1,800 qubits and 1,290 AFM couplers, over 120 experiments with and without shim. Both magnetization and correlation distributions are tightened substantially. Outliers in shimmed spin–spin correlation are symmetry classes near the boundary of the lattice.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Evolution time required to converge from two distant initial states in an 1,800-spin lattice.

a–c, We initialize the quantum simulation (QA) and the classical Monte Carlo simulation (QMC) with single-spin updates (that is, no cluster updates) in two classical ground states, shown for L = 6 with pink and blue representing up and down Ising spins, respectively. One is a clock state (a) with order parameter \(m=2/\sqrt{3}\). The other is a striped state (b), which has m = 0 and is far from other classical ground states in Hamming distance. As these initial states are evolved in either QA or QMC for increasing evolution times, m converges towards a steady state (c) regardless of initial condition. The uptick of m for long QA evolution may be a signature of on-chip cooling during evolution. d, The time required to converge m for the two initial conditions to within 0.3 of each other increases with s, as thermal and quantum fluctuations drop and dynamics slow. This indicates that QMC simulates only the equilibrium statistics of quantum evolution—not the dynamics.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Phase diagram of the square-octagonal lattice from Monte Carlo simulations with toroidal boundary conditions.

a, b, We estimate the upper (a) and lower (b) KT phase transition via universal collapse of susceptibility data, varying temperature for several values of Γ/J (shown: Γ/J = 1.2); lower collapse is imperfect. c, Power-law scaling of m with L at upper and lower critical temperatures with critical exponents from two-dimensional XY universality. Lines show power-law regression. d, Crossing of the normalized Binder cumulant for models with β = 3.5L/Γ gives an estimate of the quantum critical point Γ/J ≈ 1.76 (the inset shows the collapse of Binder cumulant across system sizes). e, From this data we derive a picture of the phase diagram of the square-octagonal lattice with JFM = −1.8JAFM. f, In the perturbative limit, the critical temperature of the square-octagonal lattice is determined by the energy splitting of four-qubit FM chains. Therefore, the perturbative phase boundary corresponding to the triangular lattice’s linear perturbative phase boundary has a quartic form (boundary shown is proportional to Γ 4, fitted by eye).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Effect of classical quench on QMC samples.

a, Distributions of classical energy differ greatly between QA and QMC output, with QA giving much lower classical energies. b, When a local quench is performed on QMC output, removing local excitations at the single-qubit level and the four-qubit chain level, the energy distribution matches QA closely. c, Quenching increases \(\left\langle \left|\psi \right|\right\rangle \) by 0.02 in these QMC samples. Samples are collected for s = 0.26, T = 8.4 mK.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

King, A.D., Carrasquilla, J., Raymond, J. et al. Observation of topological phenomena in a programmable lattice of 1,800 qubits. Nature 560, 456–460 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0410-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0410-x

This article is cited by

-

Point convolutional neural network algorithm for Ising model ground state research based on spring vibration

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Quantum fluctuations drive nonmonotonic correlations in a qubit lattice

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Kagome qubit ice

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Accelerated quantum Monte Carlo with probabilistic computers

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Quantum optimization within lattice gauge theory model on a quantum simulator

npj Quantum Information (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.