Abstract

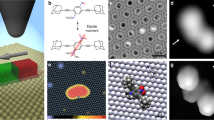

Scanning probe microscopy makes it possible to image and spectroscopically characterize nanoscale objects, and to manipulate1,2,3 and excite4,5,6,7,8 them; even time-resolved experiments are now routinely achieved9,10. This combination of capabilities has enabled proof-of-principle demonstrations of nanoscale devices, including logic operations based on molecular cascades11, a single-atom transistor12, a single-atom magnetic memory cell13 and a kilobyte atomic memory14. However, a key challenge is fabricating device structures that can overcome their attraction to the underlying surface and thus protrude from the two-dimensional flatlands of the surface. Here we demonstrate the fabrication of such a structure: we use the tip of a scanning probe microscope to lift a large planar aromatic molecule (3,4,9,10-perylenetetracarboxylic-dianhydride) into an upright, standing geometry on a pedestal of two metal (silver) adatoms. This atypical and surprisingly stable upright orientation of the single molecule, which under all known circumstances adsorbs flat on metals15,16, enables the system to function as a coherent single-electron field emitter. We anticipate that other metastable adsorbate configurations might also be accessible, thereby opening up the third dimension for the design of functional nanostructures on surfaces.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Eigler, D. M. & Schweizer, E. K. Positioning single atoms with a scanning tunnelling microscope. Nature 344, 524–526 (1990).

Ternes, M., Lutz, C. P., Hirjibehedin, C. F., Giessibl, F. J. & Heinrich, A. J. The force needed to move an atom on a surface. Science 319, 1066–1069 (2008).

Wagner, C. et al. Scanning quantum dot microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 026101 (2015).

Stipe, B. C., Rezaei, M. A. & Ho, W. Single-molecule vibrational spectroscopy and microscopy. Science 280, 1732–1735 (1998).

Heinrich, A. J., Gupta, J. A., Lutz, C. P. & Eigler, D. M. Single-atom spin-flip spectroscopy. Science 306, 466–469 (2004).

Müllegger, S. et al. Radio frequency scanning tunneling spectroscopy for single-molecule spin resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 133001 (2014).

Baumann, S. et al. Electron paramagnetic resonance of individual atoms on a surface. Science 350, 417–420 (2015).

Esat, T. et al. A chemically driven quantum phase transition in a two-molecule Kondo system. Nat. Phys. 12, 867–873 (2016).

Loth, S., Etzkorn, M., Lutz, C. P., Eigler, D. M. & Heinrich, A. J. Measurement of fast electron spin relaxation times with atomic resolution. Science 329, 1628–1630 (2010).

Saunus, C., Bindel, J. R., Pratzer, M. & Morgenstern, M. Versatile scanning tunneling microscopy with 120 ps time resolution. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 051601 (2013).

Heinrich, A. J., Lutz, C. P., Gupta, J. A. & Eigler, D. M. Molecule cascades. Science 298, 1381–1387 (2002).

Fuechsle, M. et al. A single-atom transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 242–246 (2012).

Donati, F. et al. Magnetic remanence in single atoms. Science 352, 318–321 (2016).

Kalff, F. E. et al. A kilobyte rewritable atomic memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 926–929 (2016).

Witte, G. & Wöll, C. Growth of aromatic molecules on solid substrates for applications in organic electronics. J. Mater. Res. 19, 1889–1916 (2004).

Maurer, R. J. et al. Adsorption structures and energetics of molecules on metal surfaces: bridging experiment and theory. Prog. Surf. Sci. 91, 72–100 (2016).

Eremtchenko, M., Schaefer, J. A. & Tautz, F. S. Understanding and tuning the epitaxy of large aromatic adsorbates by molecular design. Nature 425, 602–605 (2003).

Temirov, R., Soubatch, S., Luican, A. & Tautz, F. S. Free-electron-like dispersion in an organic monolayer film on a metal substrate. Nature 444, 350–353 (2006).

Schuler, B. et al. Adsorption geometry determination of single molecules by atomic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 106103 (2013).

Toher, C. et al. Electrical transport through a mechanically gated molecular wire. Phys. Rev. B 83, 155402 (2011).

Green, M. F. et al. Patterning a hydrogen-bonded molecular monolayer with a hand-controlled scanning probe microscope. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 5, 1926–1932 (2014).

Kocić, N. et al. Periodic charging of individual molecules coupled to the motion of an atomic force microscopy tip. Nano Lett. 15, 4406–4411 (2015).

Forbes, R. G. Physics of generalized Fowler–Nordheim-type equations. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 26, 788–793 (2008).

Gundlach, K. Zur Berechnung des Tunnelstroms durch eine trapezförmige Potentialstufe. Solid-State Electron. 9, 949–957 (1966).

Fink, H. W. Mono-atomic tips for scanning tunneling microscopy. IBM J. Res. Develop. 30, 460–465 (1986).

Oshima, C. et al. Young’s interference of electrons in field emission patterns. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 038301 (2002).

Fève, G. et al. An on-demand coherent single electron source. Science 316, 1169–1172 (2007).

Cocker, T. L., Peller, D., Yu, P., Repp, J. & Huber, R. Tracking the ultrafast motion of a single molecule by femtosecond orbital imaging. Nature 539, 263–267 (2016).

Longchamp, J. N. et al. Imaging proteins at the single-molecule level. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1474–1479 (2017).

Weiß, S. et al. Exploring three-dimensional orbital imaging with energy-dependent photoemission tomography. Nat. Commun. 6, 8287 (2015).

Gross, L., Mohn, F., Moll, N., Liljeroth, P. & Meyer, G. The chemical structure of a molecule resolved by atomic force microscopy. Science 325, 1110–1114 (2009).

Schmidt, M. W. et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 14, 1347–1363 (1993).

Weymouth, A. J., Hofmann, T. & Giessibl, F. J. Quantifying molecular stiffness and interaction with lateral force microscopy. Science 343, 1120–1122 (2014).

Demuth, J. E., Christmann, K. & Sanda, P. N. The vibrations and structure of pyridine chemisorbed on Ag(111): the occurrence of a compressional phase transformation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 76, 201–206 (1980).

Lee, I., Son, S., Shin, T. & Hahn, J. R. Direct observation of the conformational transitions of single pyridine molecules on a Ag(110) surface induced by long-range repulsive intermolecular interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 014706 (2017).

Ulman, A. Formation and structure of self-assembled monolayers. Chem. Rev. 96, 1533–1554 (1996).

Blyholder, G. Molecular orbital view of chemisorbed carbon monoxide. J. Phys. Chem. 68, 2772–2777 (1964).

Cai, Y., Guo, Y., Xu, X. & Jiang, B. First-principle investigation 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene molecule adsorption on Cu(110)-(2 × 1)O surface. Surf. Sci. 665, 83–88 (2017).

Jasper-Tönnies, T. et al. Conductance of a freestanding conjugated molecular wire. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 066801 (2017).

Gerhard, L. et al. An electrically actuated molecular toggle switch. Nat. Commun. 8, 14672 (2017).

Chelvayohan, M. & Mee, C. H. B. Work function measurements on (110), (100) and (111) surfaces of silver. J. Phys. C 15, 2305–2312 (1982).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Kronik and S. Sarkar (Weizmann Institute of Science) and M. Rohlfing (Universität Münster) for performing DFT calculations of standing molecules (not reported here).

Reviewer information

Nature thanks T. Greber, A. Heinrich and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.E., F.S.T. and R.T. conceived the research. T.E., N.F. and R.T. conducted the NC-AFM/STM experiments and analysed the resultant experimental data. T.E., R.T. and F.S.T. interpreted the data. T.E. carried out simulations and prepared the figures. T.E., R.T. and F.S.T. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 A standing NTCDA molecule.

a, Constant-current STM image of an NTCDA (1,4,5,8-naphthalenetetracarboxylic-dianhydride) molecule and two silver adatoms, recorded before the assembly of a NTCDA + 2Ag complex. b, AFM image of a standing NTCDA molecule, recorded at a tip height of z = 13.5 Å above the surface. c, Schematic side view of standing PTCDA and NTCDA molecules. The length difference of 4.2 Å between the two molecules corresponds well with the tip-height difference Δz = 17.5 Å − 13.5 Å = 4.0 Å between the AFM images of the standing PTCDA (see Fig. 1f) and NTCDA (b) molecules.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Two standing PTCDA molecules.

a, Constant-current STM image of two PTCDA + 2Ag complexes that were assembled in the same way as shown in Fig. 1b. b, AFM image of the standing molecules, recorded at tip height of z = 17.5 Å above the surface (left). One of the standing molecules is then moved closer to the other by the lateral manipulation procedure demonstrated in Extended Data Fig. 3a (right).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Manipulation of the standing molecule.

a, Lateral movement of the standing molecule by tip approach. The white cross in the AFM image on the left indicates the tip position during manipulation (V = 2 mV). b, Rotational movement of the standing molecule by a current pulse. The white cross in the AFM image on the left indicates the tip position during manipulation (z = 17.5 Å). The molecule jumps from a red (symmetric) to a black (asymmetric) position (see Methods). c, Toppling over the standing molecule to the surface by using a positive bias-voltage sweep. The white cross in the AFM image on the left indicates the tip position during manipulation (z = 17.5 Å). The constant-current STM image on the right shows the PTCDA + 2Ag complex after the toppling.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Determining the tilting stiffness of the standing molecule.

a, Approach along the y direction as defined in Fig. 2a, b. Parameters are d = 3.25 Å, l = 12.9 Å and 2a = 4.55 Å; d + l ≠ z, because the tip height z is measured from the centre of the uppermost surface layer, whereas l is measured from the centre of the two silver adatoms in the PTCDA + 2Ag complex. b, Approach along the x direction as defined in Fig. 2a, b. The sketch on the left shows a side view, whereas on the right a perspective view onto the top of the molecule is drawn. c, Left, best fit (green line) of the experimental F x (on x axis, red circles), obtained with the model in equation (8) and κ θ = 630 zN m rad−1 (κ = 0.38 N m−1). Black data points display F y (on y axis), fitted with equation (4) (blue line). d, As in c, but for a simulated curve (green) with κ θ = 20.0 aN m rad−1 (κ = 12.02 N m−1), which is too stiff to reproduce the experimental F x (red). e, As in c, but for a simulated curve (green) with κ θ = 310 zN m rad−1 (κ = 0.19 N m−1), which is too soft. For a detailed discussion of this figure, see Methods. Tilt angles θeq and linear elongations xm are plotted in the middle and right panels in c–e.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Orientation of the standing molecule.

The histogram (left) shows all evaluated orientations of standing PTCDA molecules on the Ag(111) surface. The angle is defined as in Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 3b. In total, we evaluated the orientations of 128 standing PTCDA molecules. The possible orientations on the Ag(111) surface are illustrated on the right. Black and red symbols indicate the possible positions of one of the silver atoms at the surface contact, when the other sits in the centre. See also Fig. 2d and Methods.

Extended Data Fig. 6 The Ag(111) lattice.

Constant-current STM image of the atomically resolved Ag(111) surface. In all experiments, the Ag(111) lattice orientation was as shown in this image.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Field-emission images.

a–c, Successive field-emission images (without the background) recorded at z = 73.5 Å and bias voltages of V = −24.00 V (a), V = −24.35 V (b) and V = −24.70 V (c).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Esat, T., Friedrich, N., Tautz, F.S. et al. A standing molecule as a single-electron field emitter. Nature 558, 573–576 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0223-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0223-y

This article is cited by

-

Field emission microscope for a single fullerene molecule

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Defect-implantation for the all-electrical detection of non-collinear spin-textures

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Sub-cycle atomic-scale forces coherently control a single-molecule switch

Nature (2020)

-

Quantitative imaging of electric surface potentials with single-atom sensitivity

Nature Materials (2019)

-

Tunable giant magnetoresistance in a single-molecule junction

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.