Abstract

Haramiyida was a successful clade of mammaliaforms, spanning the Late Triassic period to at least the Late Jurassic period, but their fossils are scant outside Eurasia and Cretaceous records are controversial1,2,3,4. Here we report, to our knowledge, the first cranium of a large haramiyidan from the basal Cretaceous of North America. This cranium possesses an amalgam of stem mammaliaform plesiomorphies and crown mammalian apomorphies. Moreover, it shows dental traits that are diagnostic of isolated teeth of supposed multituberculate affinities from the Cretaceous of Morocco, which have been assigned to the enigmatic ‘Hahnodontidae’. Exceptional preservation of this specimen also provides insights into the evolution of the ancestral mammalian brain. We demonstrate the haramiyidan affinities of Gondwanan hahnodontid teeth, removing them from multituberculates, and suggest that hahnodontid mammaliaforms had a much wider, possibly Pangaean distribution during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

14 August 2018

The asterisked footnote to Extended Data Table 1 should state ‘*Including Thomasia and Haramiyavia’. This has been corrected online.

References

Grossnickle, D. M. & Polly, P. D. Mammal disparity decreases during the Cretaceous angiosperm radiation. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20132110 (2013).

Hahn, G., Sigogneau-Russell, D. & Wouters, G. New data on Theroteinidae—their relations with Paulchoffatiidae and Haramiyidae. Geol. Paleontol. 23, 205–215 (1989).

Butler, P. M. Review of the early allotherian mammals. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 45, 317–342 (2000).

Luo, Z.-X., Gatesy, S. M., Jenkins, F. A. Jr, Amaral, W. W. & Shubin, N. H. Mandibular and dental characteristics of Late Triassic mammaliaform Haramiyavia and their ramifications for basal mammal evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E7101–E7109 (2015).

Butler, P. M. & Hooker, J. J. New teeth of allotherian mammals from the English Bathonian, including the earliest multituberculates. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 50, 185–207 (2005).

Zheng, X., Bi, S., Wang, X. & Meng, J. A new arboreal haramiyid shows the diversity of crown mammals in the Jurassic period. Nature 500, 199–202 (2013).

Zhou, C. F., Wu, S., Martin, T. & Luo, Z.-X. A Jurassic mammaliaform and the earliest mammalian evolutionary adaptations. Nature 500, 163–167 (2013).

Meng, J., Bi, S., Zheng, X. & Wang, X. Ear ossicle morphology of the Jurassic euharamiyidan Arboroharamiya and evolution of mammalian middle ear. J. Morphol. 279, 441–457 (2018).

Bi, S., Wang, Y., Guan, J., Sheng, X. & Meng, J. Three new Jurassic euharamiyidan species reinforce early divergence of mammals. Nature 514, 579–584 (2014).

Han, G., Mao, F., Bi, S., Wang, Y. & Meng, J. A Jurassic gliding euharamiyidan mammal with an ear of five auditory bones. Nature 551, 451–456 (2017).

Luo, Z.-X. et al. New evidence for mammaliaform ear evolution and feeding adaptation in a Jurassic ecosystem. Nature 548, 326–329 (2017).

Meng, Q.-J. et al. New gliding mammaliaforms from the Jurassic. Nature 548, 291–296 (2017).

Rowe, T. B. Osteological Diagnosis of Mammalia, L. 1758, and its Relationship to Extinct Synapsida. PhD thesis, Univ. California, Berkeley (1986).

Sigogneau-Russell, D. First evidence of Multituberculata (Mammalia) in the Mesozoic of Africa. Neues Jahrb. Geol. Paläontol. Abh. 1991, 119–125 (1991).

McDonald, A. T. et al. New basal iguanodonts from the Cedar Mountain formation of Utah and the evolution of thumb-spiked dinosaurs. PLoS ONE 5, e14075 (2010).

Gingerich, P. D. & Smith, B. H. in Size and Scaling in Primate Biology (ed. Jungers, W. L.) 257–272 (Plenum, New York, 1984).

Millien, V. & Bovy, H. When teeth and bones disagree: body mass estimation of a giant extinct rodent. J. Mamm. 91, 11–18 (2010).

Krause, D. W. et al. First cranial remains of a gondwanatherian mammal reveal remarkable mosaicism. Nature 515, 512–517 (2014).

Krause, D. W., Wible, J. R., Hoffmann, S., Groenke, J. R., O’Connor, P. M., Holloway, W. L. & Rossie, J. B. Craniofacial morphology of Vintana sertichi (Mammalia, Gondwanatheria) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 34, 14–109 (2014).

Langevin, P. & Barclay, R. M. R. Hypsignathus monstrosus. Mamm. Species 357, 1–4 (1990).

Hahn, G. & Hahn, R. New multituberculate teeth from the Early Cretaceous of Morocco. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 48, 349–356 (2003).

Rowe, T. B., Macrini, T. E. & Luo, Z.-X. Fossil evidence on origin of the mammalian brain. Science 332, 955–957 (2011).

Macrini, T. E., Rougier, G. W. & Rowe, T. Description of a cranial endocast from the fossil mammal Vincelestes neuquenianus (Theriiformes) and its relevance to the evolution of endocranial characters in therians. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 290, 875–892 (2007).

Luo, Z.-X. et al. Evolutionary development in basal mammaliaforms as revealed by a docodontan. Science 347, 760–764 (2015).

Heinrich, W.-D. First haramiyid (Mammalia, Allotheria) from the Mesozoic of Gondwana. Foss. Rec. 2, 159–170 (1999).

Anantharaman, S., Wilson, G. P., Das Sarma, D. C. & Clemens, W. A. A possible Late Cretaceous “haramiyidan” from India. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 26, 488–490 (2006).

Brikiatis, L. Late Mesozoic North Atlantic land bridges. Earth Sci. Rev. 159, 47–57 (2016).

Dunhill, A. M., Bestwick, J., Narey, H. & Sciberras, J. Dinosaur biogeographical structure and Mesozoic continental fragmentation: a network-based approach. J. Biogeogr. 43, 1691–1704 (2016).

Rodrigues, P. G., Ruf, I. & Schultz, C. L. Study of a digital cranial endocast of the non-mammaliaform cynodont Brasilitherium riograndensis (Later Triassic, Brazil) and its relevance to the evolution of the mammalian brain. Palaontol. Z. 88, 329–352 (2014).

Macrini, T. E., Rowe, T. & Vandeberg, J. L. Cranial endocasts from a growth series of Monodelphis domestica (Didelphidae, Marsupialia): a study of individual and ontogenetic variation. J. Morphol. 268, 844–865 (2007).

Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003).

Lewis, P. O. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst. Biol. 50, 913–925 (2001).

Wagner, P. J. Modelling rate distributions using character compatibility: implications for morphological evolution among fossil invertebrates. Biol. Lett. 8, 143–146 (2012).

Harrison, L. B. & Larsson, H. C. Among-character rate variation distributions in phylogenetic analysis of discrete morphological characters. Syst. Biol. 64, 307–324 (2015).

Goloboff, P. A., Farris, J. S. & Nixon, K. C. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics 24, 774–786 (2008).

Hoffmann, S., O’Connor, P. M., Kirk, E. C., Wible, J. R. & Krause, D. W. Endocranial and inner ear morphology of Vintana sertichi (Mammalia, Gondwanatheria) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 34, 110–137 (2014).

Ruf, I., Luo, Z.-X. & Martin, T. Reinvestigation of the basicranium of Haldanodon exspectatus (Mammaliaformes, Docodonta). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 33, 382–400 (2013).

Hahn, G. & Hahn, R. in Guimarota: A Jurassic Ecosystem (eds. Martin, T. & Krebs, B.) 97–108 (Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, 2000).

Kermack, K. A., Mussett, F. & Rigney, H. W. The skull of Morganucodon. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 71, 1–158 (1981).

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., Cifelli, R. L. & Luo, Z.-X. Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure (Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Irmis, C. Levitt-Bussian and the Natural History Museum of Utah (UMNH); Utah Geological Survey, which funded the excavation and preparation of the specimen; A. R. C. Milner who discovered Andrew’s Site (UMNH 1207); Utah Friends of Paleontology and volunteers who helped with excavation; Bureau of Land Management for permission (BLM permit #UTEX-05-031) and site supervision in 2005 under J. Cavin; J. Cavin for initial preparation and S. Madsen for final preparation of the specimen; T. Martin for the Paulchoffatia jaw from the Guimarota Mammals Collection (GUI MAM) illustrated in Fig. 2c; E. Hsu, S. Merchant and University of Utah Small Animal Imaging facility, Salt Lake City, for high-resolution X-ray computed tomography scanning; J. Lungmus and A. Neander for additional scanning at the University of Chicago PaleoCT; E. Seiffert (USC) for helpful comments. The specimen is housed at UMNH, Salt Lake City.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks S. Hoffmann and T. Martin for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.I.K. conducted fieldwork and oversaw laboratory preparation of the specimen; A.K.H., Z.-X.L. and J.A.S. scanned the specimen using computed tomography; A.K.H. analysed the data and conducted the computed tomography reconstructions; A.K.H. illustrated the specimen, and A.K.H. and Z.-X.L. composed the figures; A.K.H., D.M.G. and Z.-X.L. conducted the phylogenetic analysis; and A.K.H., D.M.G., J.I.K., J.A.S. and Z.-X.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

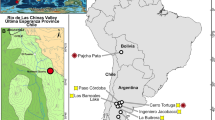

Extended Data Fig. 1 Stratigraphic section through Andrew’s Site and quarry map.

a, Revised type section of the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation showing the stratigraphic position of Andrew’s Site (UMNH 1207). Modified from McDonald et al.15. b, Quarry map of Andrew’s Site. The position of the mammaliaform skull UMNH VP 16771 is indicated in red.

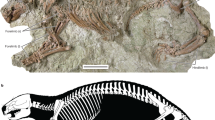

Extended Data Fig. 2 Skull and interpretive drawings of C. wahkarmoosuch UMNH VP 16771.

a, b, Specimen shown in dorsal (a) and ventral (b) views. Grey areas represent matrix infill, hatched areas represent crushed/desiccated bones, dashed lines represent cracks through the specimen. c, Stereopair of the left side of skull in ventral view to show broad, shallow squamosal glenoid. as, alisphenoid (epipterygoid); bs, basisphenoid; C, upper canine alveolus; e n, external naris; f, frontal; f alt, anterior lateral trough foramen (cavum epiptericum ventral opening); f i, incisive foramen; f l, lacrimal foramen; f m-pal, maxillopalatine foramen; f pl, perilymphatic groove/foramen; f pt-par, pterygoparoccipital foramen; g, squamosal glenoid; I3, second upper incisor alveolus; j, jugal; l, lacrimal; m, maxilla; n, nasal; o, occipital; p, parietal; pal, palatine; PC4, in situ posterior upper postcanine (molar); pe, petrosal; pm, premaxilla; pt, pterygoid; sq, squamosal; v, vomer.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Skull and interpretive drawings of C. wahkarmoosuch UMNH VP 16771 (continued).

Specimen shown in left lateral view. Grey areas represent matrix infill, dashed lines represent broken/reconstructed bones. f in, infraorbital foramen; f v, lateral external vascular foramen; os, orbitosphenoid; t, tabular.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cranial foramina and sinuses in the braincase of C. wahkarmoosuch.

a, Line drawing of the posterior skull in right oblique (anterolateral) view. b, Computed tomography transparency of the skull in left oblique view, showing the prootic sinus and associated branches of the stapedial artery (light green). d m, diploetica magna; r i, stapedial artery (ramus inferior); r s, stapedial artery (ramus superior); r t, ramus temporalis; V1, orbital vacuity (hypothesized exit for ophthalmic branch of trigeminal nerve); V3, foramen pseudovale (hypothesized exit for mandibular branch of trigeminal nerve).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cranial vault and endocranial features of Cifelliodon.

a–c, Comparison of occiputs of the cynodont Thrinaxodon liorhinus (based in part on University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) 40466) (a), C. wahkarmoosuch (b) and Vintana sertichi (based on figure 1 of Krause et al.18) (c). Shaded bones in b and c emphasize sutural union of postparietal and paroccipital process. Skulls are not shown to scale. d–h, Brain endocasts. Cifelliodon endocast shown in left lateral (d) and posterior oblique (e) views. Skull of Vintana in lateral view shown externally (f) and with endocranial features exposed (g) (modified from figure 1 of Hoffmann et al.36 flipped for comparison). Skull of Hadrocodium (h) shown as a representative plesiomorphic mammaliaform (modified from figure 1 of Rowe et al.22; flipped for comparison). Numbers represent characters and character states described in the Supplementary Information. cb, cerebellar hemisphere; eo, exoccipital; f j, cast of jugular foramen within perilymphatic fossa; nc, region of neocortex; ob, olfactory bulb; p pr, paroccipital process; pf, paraflocculus cast; pp, postparietal; so, supraoccipital; II, III, IV, V1, exit for anterior cranial nerves near sphenorbital fissure; V3, V2, roots of mandibular (and maxillary?) branch of trigeminal nerve; IX, X, roots of glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Derived condition of Cifelliodon and other haramiyidans in root morphology and root implant of upper teeth, in contrast to the primitive condition of mammaliaforms.

a, C. wahkarmoosuch (UMNH VP16771): procumbent implant of incisor roots. b, The Madagascar mammaliaform Vintana with procumbent incisor roots (based on figure 2 of Krause et al.18). c, Haramiyavia: the first three incisors are procumbent with elongate and procumbent roots (top-labial view, left–right flipped left premaxillary with in situ incisors; bottom-lingual view of left incisors; based on supplementary figure 1 of Luo et al.4). d, Morganucodon oehleri (type specimen, photograph was made by Z.-X.L.): all upper teeth (including incisors) are vertical. e, Haldanodon exspectatus: upper teeth are all vertical, orientation of incisors shown by their vertical alveoli (resegmented from the previously published dataset37). The typical condition for implant of upper teeth is vertical for most mammaliaforms. By comparison the primitive condition of most mammaliaforms, the procumbent incisor implant is a derived condition for haramiyidans, either on all of the incisors (Cifelliodon and Vintana) or on anterior incisors (Haramiyavia).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Derived condition of Cifelliodon and other haramiyidans in orientation and implant of incisor and postcanine roots, in contrast to the typical condition of multituberculates (in labial or lingual views).

a, C. wahkarmoosuch (UMNH VP16771): procumbent implant of incisor roots. b, V. sertichi with procumbent (hypertrophied) incisor roots (based on figure 2 of Krause et al.18). c, Haramiyavia: the first three incisors are procumbent with elongate and procumbent roots (top-labial view, left–right flipped left premaxillary with in situ incisors; bottom-lingual view of left incisors; based on supplementary figure 1 of Luo et al.4). d, Henkelodon naias (Paulchoffatiidae, Multituberculata: GUI-MAM-28-74). e, Kuehneodon dryas (Paulchoffatiidae, Multituberculata: VJ400-155). f, Kuehneodon simpsoni (Paulchoffatiidae, Multituberculata; based on figure 12.5 from Hahn & Hahn38, reproduced with permission). g, Kryptobaatar dashzevegi (Djadochtatheria; Multituberculata; image from http://digimorph.org/). The procumbent orientation and tooth implant of incisors is a derived condition of haramiyidans (including Cifelliodon), in contrast to the vertically implanted incisors and postcanines of most Mesozoic multituberculates, including basal paulchoffatiids, plagiaulacids and djadochtatherians. The vertical implant of incisors in multituberculate condition is plesiomorphic, as it is also shared by other stem mammaliaforms.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Derived condition of Cifelliodon and other haramiyidan in orientation and implant of incisor roots, in contrast to the typical condition of other stem mammaliaforms and most multituberculates (palatal view).

a, C. wahkarmoosuch (UMNH VP16771): procumbent implant of incisor roots. b, V. sertichi with procumbent (hypertrophied) incisor roots (based on figure 2 of Krause et al.18). c, Haramiyavia: the first three incisors are procumbent with elongate and procumbent roots (ventral view of left incisors and premaxillary: left with premaxillary; right premaxillary rendered invisible: based on supplementary figure 1 of Luo et al.4). d, Morganucodon watsoni (based on figure 6 of Kermack et al.39). e, Haldanodon exspectatus: vertical orientation of incisors shown by their vertical alveoli (resegmented from the previously published dataset37). f, K. simpsoni (Paulchoffatiidae, Multituberculata) (adapted with permission from Kielan-Jaworowska et al.40). g, Paulchoffatia delgadoi (Paulchoffatiidae, Multituberculata) (adapted with permission from Kielan-Jaworowska et al.40). h, K. dryas (Paulchoffatiidae, Multituberculata) (adapted with permission from Kielan-Jaworowska et al.40). i, Sloanbaatar mirabilis (Djadochtatheria, Multituberculata) (adapted with permission from Kielan-Jaworowska et al.40). j, Kamptobaatar kuczynskii (Djadochtatheria, Multituberculata) (adapted with permission from Kielan-Jaworowska et al.40). k, Ptilodus montanus (adapted with permission from Kielan-Jaworowska et al.40). l, Taeniolabis taoensis (adapted with permission from Kielan-Jaworowska et al.40). The procumbent implant of upper incisors is a derived condition for haramiyidans, either on all of the incisors (Cifelliodon and Vintana) or on anterior incisors (Haramiyavia). By comparison, the plesiomorphic condition of incisor implantation is vertical for most stem mammaliaforms (for example, Morganucodon and Haldanodon). All Mesozoic multituberculates have vertical implant of upper incisors, including basal-most paulchoffatiids that are preserved with upper incisors, plagiaulacids and djadochtatherians. However, the Cenozoic ptilodontid and taeniolabidid multituberculates show procumbent incisors. Because Mesozoic multituberculates have vertical implantation of incisors, the procumbent incisors of ptilodontids and taeniolabidids are interpreted to be secondarily derived and convergent (k, l).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Phylogenetic results.

a, Consensus cladogram from Bayesian analysis in MrBayes 3.231. Branches are not drawn proportional to lengths. Clade support values shown at the nodes are Bayesian posterior probabilities (0.50–1.0). b, Strict consensus of 1,920 equally parsimonious trees (tree score = 2,776 steps; consistency index = 0.317; retention index = 0.795) from the parsimony analysis in TNT 1.135. Values at nodes are bootstrap values above 50% (first number (before the solidus)) and Bremer indices (second number (after the solidus)).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains the Supplementary Materials and Methods parts A-G.

Video 1:

3D yaw of cranium of Cifelliodon (UMNH VP 16771).

Video 2:

3D roll of cranium of Cifelliodon (UMNH VP 16771).

Video 3:

3D roll of dentition of Cifelliodon (UMNH VP 16771).

Video 4:

3D roll of brain endocast of Cifelliodon (UMNH VP 16771).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huttenlocker, A.K., Grossnickle, D.M., Kirkland, J.I. et al. Late-surviving stem mammal links the lowermost Cretaceous of North America and Gondwana. Nature 558, 108–112 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0126-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0126-y

This article is cited by

-

Global latitudinal gradients and the evolution of body size in dinosaurs and mammals

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Evolutionary origins of the prolonged extant squamate radiation

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Africa’s oldest dinosaurs reveal early suppression of dinosaur distribution

Nature (2022)

-

Jaw shape and mechanical advantage are indicative of diet in Mesozoic mammals

Communications Biology (2021)

-

A monotreme-like auditory apparatus in a Middle Jurassic haramiyidan

Nature (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.