Abstract

As clinicians and surgeons, the experience of prostate cancer is one that happens on an almost daily basis. We are used to the feeling of making a diagnosis, to reassuring our patients, to the calm and sterility of an operating theatre, and to the worry of waiting for pathology results. For our patients, this experience is new and often terrifying, and only rarely do we consider the two experiences — doctor and patient — together. If we are to ask a patient to tell their story in writing, there are few people who are better placed to do so than one who does this professionally and who has done so for the best part of four decades. In this Viewpoint, Stephen Fry describes his prostate cancer journey from initial concerns through diagnosis and surgery to follow-up, alongside the same story told by his surgeon, Ben Challacombe. Thus, this unique article reminds us that the same events provide a different experience for patient and surgeon and enables us to consider both sides of the scalpel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prostate & I

Stephen Fry

If one was to search about for a definition of physical good health, perhaps you could do no better than describing it as that state which gives one no cause to think about one’s body other than how to clothe it, feed it, and rest it. Most people, as doctors know, are in physical good health for most of the time. Our systems have evolved to operate without much maintenance. Mental health issues aside, I am in that happy majority that has bumbled through life with very few issues if one excludes those that were self-inflicted, like broken bones and wrenched muscles (and, for the sake of completeness, one student alcoholic spree that required a stomach pump). The nature of my peculiar profession means that for most of my life I have enjoyed an added advantage that allows me to be more insouciant than most, for my health has been more consistently and constantly monitored than is perhaps usual. Being an actor requires attendance, punctuality, reliability, and dependability: every new production begins for me not with a costume fitting or rehearsal, but a check-up. Without a medical all clear, insurance companies won’t cover you and without cover a producer can’t risk hiring you. So all actors lucky enough to be in regular work will routinely find themselves in a doctor’s surgery several times a year having their abdomens palpated, blood pressure taken, and relevant bodily fluids drawn. Familiarity breeds confidence and over the years I have never gone home from a medical examination and then lain awake at night worrying about what the results might be.

But one afternoon in November 2017, my doctor Tony called me up after one such routine inspection, which coincided with the annual flu jab, to tell me that my PSA levels were higher than he liked. “Not startlingly high, but perhaps worth investigating further”, he said.

And so it begins. My story is no different from that of thousands and thousands of men every year in the UK alone.

A quickly arranged MRI scan confirmed that there was indeed, in Tony’s words, “something mischievous” going on in the prostate region. I had suffered no symptoms whatsoever to indicate any problems with the prostate, but the image certainly revealed enough for Tony to decide that a urologist should now take a look at me. He selected as my consultant Professor Roger Kirby of the Prostate Centre in London. I discovered that a couple of friends of mine had been under Roger’s care in the past and his stellar reputation and encouraging Wikipedia entry made me feel I would be in the best possible hands. I mention this because — as all medical practitioners of every kind will know — the moment their patients are given any diagnosis or referral, they will reach for the Internet. Must be maddening for the professional, but how can we help ourselves?

Roger was warm, friendly and fully informative. I will return to this point again and again because I cannot emphasize enough the importance to me of the interpersonal skills of the entire team who attended to me over the course of my diagnosis, treatment, recovery, and convalescence. I think this is where medical practice has most changed and advanced over the years I’ve been around. I won’t suggest that interpersonal skills trump the astounding pharmaceutical, diagnostic, clinical, surgical, and nursing advances that science and technology have brought in, but empathy, information, disclosure, eye-contact, and a hand to the shoulder have been shown, as I am sure everyone reading this will be aware, to make a real, measurable difference to outcomes and recovery times. I’m not going to make a fool of myself by claiming an understanding of stress hormones and their role in this, but I’ve spoken to enough surgeons and others to feel confident that the human contact side of my prostate cancer journey was a far from incidental part of the experience.

Back to the narrative: Roger looked at the MRI scan and determined that it was indeed suggestive enough, despite a relative low PSA count of 4.97, to justify a transrectal ultrasound and targeted biopsy. These charming intrusions into my personal space were completed quickly enough. Call me picky, but I would nonetheless be happy never to undergo such experiences again. There followed, of course, a period of waiting — every day that passes between a test and its results drags out horribly and sleep comes slowly. The words bounce around inside one’s head: “you’ve got cancer … you’ve got cancer … cancer, cancer, cancer”. The low PSA reading had initially allowed me to hope that maybe it wasn’t a serious tumour, if it was one at all. The MRI however had suggested a mass that was unlikely to be anything other than cancerous, and now analysis of the live tissue sample would settle it.

Ben Challacombe

I have worked at the Prostate Centre since late 2010, shortly after I was appointed as a consultant urological surgeon at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals. Prior to this I had completed a fellowship in robotic prostate surgery under Professor Tony Costello in Melbourne, Australia. Since then, my work has been predominantly NHS-based, my time taken up with running our own prostate cancer team and fellowship programme. In the last year, as Professor Roger Kirby has gradually stepped back from operating, I have begun to take on more of the prostate surgery in conjunction with my other colleagues at the centre.

When I heard that Stephen Fry was coming to the centre at our weekly multidisciplinary meeting I was generally pretty interested in his challenging situation, having always been a fan of his comedy work. However, when Roger asked if I wouldn’t mind taking him on as my patient I had a mixture of excitement and slight trepidation. We were in the meeting room and I remember offering to speak to him about the surgical treatment option and Roger responded that he would ask him to see me next week! Surgeons are generally confident and optimistic people and I have looked after other high-profile patients before, but this was quite special and I began wondering what he would be like, as well as how it would feel if I actually came to operate on him, and what if it didn’t go well?

Preoperative considerations

S.F

I arrived at the Prostate Centre 2 days after the biopsy to sit across from Roger once more. This was the meeting that removed doubt. This is where I learned about the Gleason score. Mine was a 4 + 4 = 8 it seems, a high enough number for such a low PSA. The prostate was seriously diseased. An adenocarcinoma sat (in my mind like one of those crystalline structures that one grew in school science labs) right on the ridged edge of the gland (I’m not qualified to use words like anterior, posterior, medial, or lateral but I’m sure there’s a neater and more precise way to designate the location). I immediately started picturing cancerous cells breaking off from the mother mass, floating away and distributing themselves about the body in undesirable regions: bladder, bone, kidney, and so forth. I had watched enough episodes of my friend Hugh Laurie’s medical drama House to feel I knew all about that dark word ‘metastasis’.

Roger’s benevolent manner, of course, is as far from the cantankerous Dr House’s as it is possible to be. He answered every question patiently, carefully, and candidly — giving me the impression that he would have been happy to sit and talk for the rest of the day and into the evening. The disease had advanced enough to need attention — active surveillance was not an option with a Gleason score of 8. Roger covered the treatment options, which essentially came down to two: should it be radiotherapy or a prostatectomy? Here Roger was able to add direct personal experience to his store of academic, medical, and surgical wisdom, for he himself had been diagnosed with a very similar carcinoma just 2 years earlier. He knew exactly what I was going through physically and mentally.

He would have known very clearly that my head was a whirl of feelings and questions. Not just the issue of metastasis, which he answered, nor that question of whether this diagnosis meant I was somehow genetically predisposed to be more prone to cancer than most. If it could happen in the prostate, I wondered, did that increase the likelihood of it happening somewhere else? He answered this with the happy news that the epidemiology suggested no such above average susceptibility. But inside my head the questions were less medical and more personal. Being someone who has lived in the public eye for the best part of four decades I was aware of the possibility of the news getting out, and I didn’t want my husband or my friends and family to have the added stress of press intrusion to deal with. And, more vainly, but no less humanly (and I suspect typically), I also wondered how well I would cope with this diagnosis and whatever it led to. Would I be brave and cheerful or would I be frightened and withdrawn? I hoped the former. There was nothing I could do to change the facts, all I could do was submit myself completely into the care of Roger. It seemed to me that they would have enough to do without worrying about me being neurotic and tediously self-pitying.

But first — another test. This time one of those PET scans in which a syringe full of radioactive gallium is sent round the system to light up the cancer wherever it lay. That scan showed the full extent of the diseased prostate as expected but also a suggestion of a trace of a hint of a suspicion of ‘avidity’ in one adjacent lymph node.

I now had a talk with the radiotherapy specialist at the Prostate Centre, Professor Heather Payne. She took me through with exemplary kindness and clarity the process of hormone therapy and X-ray treatment that comprised one of the two treatment options. Despite her cheerful optimism, I began to feel straight away that this was not the choice for me. All I have that’s worth anything, I have often told myself, is my mental energy and alertness, my memory, quickness of thought, and verbal competence. Androgen suppression can be inimical to these and I just couldn’t bear the idea of being slowed down cognitively or creatively. I’ve seen what spaying does to a tomcat and I wanted no part of it. Ill-informed, superstitious, and silly perhaps, but the upside of radiotherapy — although unquestionably attractive — was for me vitiated by the disadvantages. Also, I’ll be frank, I felt the length of time the treatment would take and the regular weekly or biweekly visits to a clinic to be zapped that it would necessitate would only increase the likelihood of the press getting wind of things. Not that Heather was so defensive of her speciality that she pushed radiotherapy…

The first surgical meeting

S.F

Roger had recently retired from active knife wielding and he now introduced me to one of the surgeons who had performed the prostatectomy on him and who was to do the same for me. Ben Challacombe and I seemed to click right away — perhaps that was just his professional skill and personal charm, but I felt instantly at ease in his presence and once more delighted to find that I was going to have every stage of the procedure and its after effects clearly explained. Ben has taken up the story from his point of view and it accords exactly with my memories, even his claiming that the word ‘anastomosis’ was of Latin origin. It is as Greek as Greek could be and I could never had said otherwise without generations of classics teachers howling with outrage and slamming me into permanent detention.

We searched around for a date for the operation — it was now mid-December and we settled on the Princess Grace Hospital in London and the second Monday in January as the best practicable place and soonest available time in which to have the diseased beast excised. Such is the modern world that I was able to look on YouTube at footage of the Da Vinci prostatectomy that Ben had helped perform on Roger.

Cancer is such a definitive word: it was now looming on the horizon of my life like a great iceberg: unavoidable, hard, cold, and real. Elliott and I went away for a Christmas holiday of Scandinavian snow, ice, huskies, and reindeer, putting thoughts of tumours and surgery out of our minds as best we could.

B.C

When Stephen Fry first walked into my consulting room I’m not sure who was more nervous about what lay ahead; probably me. The first meeting with the urologist is usually a daunting time for the man who often already suspects or knows the diagnosis of prostate cancer. With cancer, the fear of the unknown that lies ahead is considerable and can reflect on the consultation in various guises. When explaining their own situation to a new patient I always make sure I have all the key facts immediately to hand and familiarize myself with them prior to the meeting. As with Stephen’s situation, if things go to plan we will have had a multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) on the morning just before the consultation to enable me to have a look at the MRI scan and other results with the whole team. Specifically, I need to know the PSA value (around 4.9 in Stephen’s case and not particularly high), the number of cores involved with cancer in the biopsy (targeted biopsy only used) and the Gleason (or new International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP)) grade of the cancer, which was 4 + 4 = 8 (or ISUP 4 out of 5) for Stephen — that is, pretty high. I also review the MRI scan myself to ensure I know the radiological stage of the disease and the location of the main focus of disease in the prostate to aid treatment planning.

On a personal communication level, I always try and find some connection between myself and my patients, to enable a metaphorical breaking of the ice and put them more at ease. This could be a mutual interest or connection in sport, leisure, travel or place of origin, or current workplace. Now this technique falls down somewhat when you are dealing with a high-profile celebrity such as Stephen Fry, about whom I already knew quite a lot, having watched every episode of Blackadder, Fry and Laurie, and so on, not to mention the immediate moment of pinching yourself when he walks into the room. In this situation we both had a little fear running through us, although for different reasons. Not surprisingly he speaks in exactly the same familiar and recognizable voice as one knows from numerous TV shows, awards presentations, and radio podcasts.

Despite this, I think I managed to put him at ease and we found some common ground to discuss such as recent English cricket results and East Anglia, where both he and my family are from. This meant we were able to move on in a more relaxed manner and have a sensible discussion about the implications of his high-risk, locally advanced prostate cancer. We discussed in outline the treatment options and the pros and cons of surgery (robotic radical prostatectomy) versus external beam radiotherapy with hormonal control. Stephen was interested in the surgical option as it gave him a back-up option of radiotherapy, but hopefully enabled him to avoid the systemic effects (physical and psychological) of medical castration using antitestosterone injections. It won’t surprise you to know that Stephen had done his background reading prior to our consultation and that he has an amazing ability to both retain and assimilate medical data rapidly, meaning that I had to be extremely careful with my exact choice of words and reasoning for my recommendations.

Stephen also had a consultation with Professor Heather Payne, a colleague specializing in radiotherapy to ensure he received both sides of this complex argument on treatment options. This approach is always recommended for men facing this difficult dilemma and ensures the decision is made having had a balanced view from both main parties. He then had a week or two to make his choice and underwent a staging PSMA–PET scan, which is becoming the new gold-standard test to rule out metastatic spread for prostate cancer.

After the initial consultation, Stephen, like any patient, had some time to evaluate his options. He was attracted to the chance to get the cancer out of his body in one relatively swift episode and also liked the thought of avoiding hormonal treatment but keeping radiotherapy in reserve as a backup. He was particularly worried that hormonal treatments blocking the male testosterone pathways could take away his creative edge.

Preparing for the operation

B.C

Having made up his mind to have a robotic radical prostatectomy and having undergone a PSMA–PET scan which ruled out signs of spread, I discussed with Stephen the details of the surgical procedure. I outlined the pros and cons again and then explained the specific risks and complications of the procedure itself. This explanation is often best done by dividing the issues into those that occur on the day of surgery itself (bleeding, damage to surrounding structures such as bowels, blood vessels and nerves), the key outcome measures of the operation (cancer cure, continence, and erectile function), and those other issues occurring after the operation (infection, anastomotic stricture, lymph leak or collection due to lymph node removal, skin scarring, and hernia). I always try to list these issues clearly as they are the main source of dissatisfaction after the procedure if things don’t go well. Despite this, at one point I used the word ‘anastomosis’ regarding the join between the bladder and the urethra. Stephen asked about this word and I replied it was probably “from the Latin for joining”; he quickly corrected me and explained it was from the Greek, of course!

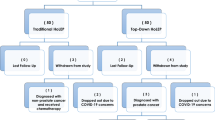

On evaluating his MRI scan in our team MDM meeting (Fig. 1) it was clear that there was a significant amount of prostate cancer outside of the right edge of the prostate gland and that getting round it all and clearing it out fully was not going to be straightforward. I did think it was possible to achieve this, but clearly I needed to counsel Stephen about the increased possibility of a positive surgical margin and a small chance of damaging structures around the prostate, such as the rectum. I advised Stephen to get as fit as he could in the next few weeks and start to practice his pelvic floor exercises to try and maximise his postoperative continence. As well as going wider around the cancer, the continence side of the operation needed to be excellent with good preservation of the structures around the urethra and hence proximity to the prostate. These are competing aims and I didn’t want to get either wrong. I went away thinking that this operation didn’t look entirely easy for a number of reasons.

S.F

We arrived at the Princess Grace on the appointed afternoon, pleased to discover that admission, triage and settling in are all designed these days to reduce the amount of time a patient stews on their own with nothing to do but fret. No sooner was I in my room than Ben and the anaesthetist came round to tell me and Elliott how the evening and night would play out. The way Elliott was involved and kept informed meant a great deal to both of us. Naturally he was worrying and just as naturally he tried to hide it as much as possible. He was made to feel a useful and trusted part of the process however, Ben going out of his way to keep him abreast of every step of the procedure. They swapped numbers, Ben promising to call Elliott the moment I was out of theatre.

The operation

B.C

The day of the operation arrived and I ensured I had everything prepared. In particular I wanted the strongest team assembled that I could to give the best chance of everything going to plan. I had asked my ex-fellow and now consultant colleague Ben Namdarian to assist me with the procedure. We have worked together on over 100 of my ~1,000 robotic prostatectomies and I valued both his judgement and his excellent technical skills. In addition I knew he wouldn’t be afraid to comment and alert me if he thought something wasn’t right. I needed the best ‘gas man’ I could find as well. I work with Dr Richard Morey in anaesthetics, who combines the two great qualities of anaesthesia from a surgeon’s perspective: high quality and slick efficiency. In addition, as this was a ‘special case’, my friend and colleague Professor Roger Kirby, with experience of over 2,000 radical prostatectomies, came as an adviser and second pair of eyes. Owing to the nasty-looking MRI scan images, we had set up an intraoperative frozen section analysis of the margins and edge of the prostate during the procedure to try and provide extra reassurance that the margins were negative and the cancer had all been removed.

Operating on a national treasure such as Stephen Fry had rather focused my mind for the preceding few weeks since we had set the date, but on the day he was as relaxed as ever and made my job as easy as possible. We went through the surgical consent form again and I checked he was happy with the plan. I took the number of his husband, Elliott, so that I could call him after the operation, which is my standard practice, and then we got on with things.

From a technical perspective all went well intraoperatively and each step proceeded according to plan. The biggest moment was around how wide to go on the right base of the prostate where the MRI scan had shown the capsule to have been breached. The apical dissection and urethral preservation was also key, as I didn’t want to be the man to make Stephen Fry incontinent! I took another little sample from the neurovascular bundle edge as reassurance after the main gland had been removed and sent them for analysis while I concentrated on doing a good lymph node removal.

S.F

A lifetime ago, I had been rushed one night from home to hospital aged 11 to have my appendix whipped out. No one had warned me beforehand that my abdomen would hurt like hell from the 7-inch incision that was standard in those days. I awoke from the operation in agony and looked down to see that I had been daubed in some strange antiseptic paint which, under the ward’s blue night lights, looked like blood. The excruciating pain and the sight of all that blood convinced me the operation had been botched and that I had been left to die. Not being able to find a button to press I got up to crawl to the Night Sister’s room, bursting my stitches along the way. It’s a nightmare that returns to me from time to time. Naturally this being the 1960s I was treated as if I was a very wicked child indeed for not lying still, making such a fuss, and causing bothersome extra work for everyone. I recovered under a cloud, half-expecting to be sent to a young offender’s institution for my bad behaviour. I rejoice to think that we can all believe such a horror could no longer happen in our hospitals, but in its broader strokes the story reveals the delicate and important psychological dilemma that faces a surgical team. All the information, eye-contact, and warm reassurance that I have mentioned is of course essential, but there is no escaping the fact that major surgery is major surgery and involves a catastrophic shock to the system for which one should be mentally primed. As far as the body is concerned you have been violently assaulted in a knife fight. In the case of a robotic radical prostatectomy you will be stabbed five times — laparoscopic precision, antisepsis, and anaesthesia notwithstanding. This means that a patient will still likely wake up in a state of battered shock if not prepared. I was so prepared, both by Ben and by my 11-year-old nightmare, that when I groggily awoke in the recovery room without any discernible pain or discomfort I thought perhaps the operation hadn’t yet taken place. But I looked across to see Ben on the phone to Elliott, carefully describing the outcome of the procedure and knew that it must indeed have happened.

Postoperative period

B.C

The first days after the operation were uncomplicated and Stephen had his drain removed on the first morning, was eating solids by the first evening, and went home on the second day. As this is a procedure that is carried out regularly, the postoperative protocol for looking after men after a robotic prostatectomy is fairly well defined. Stephen was certainly a patient patient and did all that was asked of him according to our schedule, including getting up and walking early, drinking plenty of fluids, and working hard with the physiotherapy and nursing teams.

Once home I kept in regular contact via text message and advised on some lymphatic fluid leakage from one of the port sites, which was an irritation for a few days. As well as a passage of information there were also a few moments of humorous chat, which I felt lightened the mood during this stressful time. I wanted to make it clear that he could contact me at any time if there were any issues and that I would rather know about something than not. During this time I was carrying out my normal activities including seeing patients in clinics at Guy’s Hospital and performing other robotic operations. However, throughout these first few days I had one thought at the back of my mind; what would the final pathology show and had I got him clear? I had asked for our pathologist to expedite the results but this process still takes 3–4 days and one of my little superstitions is not to ask for the results again before they are ready, in case it isn’t good news! As a cancer surgeon, this waiting period is common and potentially stressful for me too. Letting the patient know about good results is quite simply the best part of my job and really is the highlight of my week. After 3 days we had it and I called Stephen to let him know the results — Gleason 4 + 5 tumour breaching the prostatic capsule (Stage T3a), but clear margins (Fig. 2)! He was delighted and I was relieved — you don’t want to be the surgeon who doesn’t get it all out on a high-profile patient and someone whom I liked and now felt increasingly connected with.

I then saw Stephen back for the catheter removal the next week and confirmed the results and was able to show him a map of the removed prostate indicating where the cancerous area actually was. We checked the small incision sites that were healing up nicely and saw that, reassuringly, his early continence was very good with some immediate control of continence. We had discussed his pathology results at the team MDM and agreed on the timings of his next PSA tests. Stephen remembered these as St George’s day and Midsummer days to trigger his memory. He had also downloaded the ‘Squeezy’ NHS app to help with his pelvic floor exercises and so taught me something new, which I now use with lots of other patients!

S.F

The initial recovery was easy: the hospital had specialist urology nurses for day and night; I received calm kindly lessons in the details of compression stockings and catheter plumbing in the morning and felt so relatively fit and frisky that I had already decided that I was not going to spend more than one more night in the hospital if I could help it. I felt ridiculously fine all things considered. Such pain medication as I was on comprised no more than paracetamol and ibuprofen. Amusingly, the only problem Ben had faced when taking the little incision holes was the tough tissue in my lower right side: fibrous scarring that had built up all those years ago when I had endured that nightmare appendectomy had proved difficult to get through, and the pain from that was the only wince-making postoperative issue.

During surgery the excised prostate had been zipped over to a lab to check the extent of the disease; while awaiting the report back Ben had removed a string of lymph nodes just, as Lady Macbeth would have it, to make assurance doubly sure. While the cameras and robotic arms were inside me it had been deemed wise to pay attention to that slight ‘avidity’ that had shown up in one node on the PSMA–PET scan. The lab’s analysis revealed that the tumour was a little more advanced than previously thought and that the Gleason score should be adjusted upwards to a 4 + 5; from an 8 to a 9, in other words. The lymph nodes upstream and downstream of the one diseased node were all clear. The question of whether any remaining cancerous cells littered the floor of the prostate could wait for the next blood test, which couldn’t be undertaken for a good 6 weeks — the existing PSA had to clear the system first. Meanwhile, home again, I had to get myself through the initial bore of life on a catheter, life in compression stockings, life self-injecting Dalteparin, and life with a lymphatic system that seemed to think it was the Victoria Falls.

Lymphatic drainage turned out to be the only unexpected hiccup. I coughed suddenly and sharply one morning a few days after surgery: the right side incision puncture opened up and clear yellow liquid gushed out. I tamped the side with a towel, Elliott valiantly pressed against it and we waited for the flood to stop. It didn’t and, several visits to the Prostate Centre later, once the fluid had been analysed (creatinine level normal, lymphatic fluid confirmed as the exudate), I was set up with a stoma bag and spigot system to deal with the seemingly endless outflow. Over the next week or so I filled up and emptied the bags into a calibrated jug, texting Ben and the nurse with the measurements every day. Eventually the flow did dry up and the bag could be removed. Ben was extraordinarily diligent in his attention to all this, calmingly optimistic, and was clearly not concerned that this was a major issue. This was all good, but to this day I haven’t the least idea what was actually going on. Ben explained several times that this was a not uncommon issue, that it would clear up, and that the loss of liquid wasn’t in any way dangerous, worrying, or a cause for alarm. Nonetheless, out of intellectual curiosity as much as anything, I wanted to know how something as vital to systemic health as the lymphatic system could lose so many litres of fluid out of one of its necklaces of nodes without any apparent harm. What was actually happening? Where was it leaking from? How much liquid is contained within the lymphatic system at any one time, and how easily can it simply release itself into the body — between adipose layers, next to organs and glands, into the bloodstream itself, perhaps? I couldn’t really picture it. I (doubtless wickedly) came to the conclusion that gifted urologist and surgeon as Ben is, he had pretty much no idea either. Dr Google left me in trembling fear of lymphoedema and grotesquely swelling ankles, but I seem to have escaped that fate.

Final thoughts

B.C

After a 4-week period of intensive communication around the various aspects of the surgical pathway, we now signed off as Stephen went to America to prepare for his lecture tour while I got on with looking after all my other patients. Things had ultimately gone about as well as possible, but he will now need some close monitoring and our MDM will discuss all his follow-up PSA tests. Looking after Stephen has certainly been an experience I won’t forget and on which I have reflected quite a bit. As a patient, he did everything that was asked of him along this whole process and kept positive despite what must have been a challenging time for him and Elliott. Despite being in ‘show business’, he never lost his cool or temper, asked for nothing special, and was an amazing and positive person to look after. Since this time, Stephen has had two further PSA tests, which have been extremely encouraging. PSA testing in patients who have a prostate in situ is frustrating and often inaccurate, particularly with regards to screening. However, when the prostate has been removed, it becomes much more useful and accurate. His level has dropped from ~5 at surgery to 0.033 in April 2018 and then 0.027 in June, suggesting an excellent response to the prostatectomy. One of my sayings has always been that aggressive or high-grade cancers don’t necessarily obey the rules, and of course I’ve looked after enough men to know we aren’t out of the woods yet and that back-up or salvage radiotherapy might well be required in the next few years, possibly without using hormones as we’d previously discussed. However, at present the PSA is behaving nicely and I’m sure a positive physical and mental response by Stephen is helping with this. A further PSA test from August 2018 remained stable at 0.03, which is fantastic. It is not uncommon for a persistent PSA to stay stable in a healthy man and presumably this relates to a tiny focus somewhere in a lymph node or around the prostate being controlled by the body’s immune system. Although additional radiotherapy can be given in this situation, there is no immediate indication if things are so stable.

As an interesting aside, Stephen’s diagnosis and that of the BBC’s newsreader Bill Turnbull have led to a 15% increase in UK prostate cancer diagnoses in early 2018 through enhanced awareness1. For Stephen, it is a measure of the man that his impact can be so significant and far reaching. This has been reflected in a surge of men coming forward and a consequent increase in diagnostic and treatment times across the country. Stephen was of course deeply concerned about his role in causing a drop in the achievement of NHS cancer waiting targets. I have reassured him that, on the contrary, this increase in publicity for prostate cancer might have actually led to many men getting an earlier diagnosis and at a more treatable stage, and might have actually saved some lives.

S.F

Within a few weeks of surgery I was catheter and stoma bag free, attending to my pelvic floor exercises and walking 2 or 3 miles a day — briskish ambulatory exercise being the closest I ever get to exercise. It seemed likely that in 6 or 8 months, despite this full and speedy recovery from surgery, I would probably have to undergo some radiotherapeutic mopping up (dreaded hormone therapy included) to zap any final tumorous cells lying around the bed of the prostate.

But I was well — fitter and fitter every day — and within 5 weeks of the operation had no real reason to think about my condition from one day to the next. My agent’s office had started receiving a few calls from the newspapers who had wind that something was up with my health. I recorded a statement on video which I pushed out on Twitter, timed to coincide with my going off to California, where we have a house. I spent the next 2 months in America writing and working on all kinds of things, especially preparation for a very gruelling series to be presented in Canada: a trilogy of one-man shows, the cycle to be performed 13 times, so 39 performances all told. A blood test in April revealed a PSA level of 0.033 and a further test in June showed 0.027 — levels that thrillingly indicated that radiotherapy and the dreaded hormone zombification wouldn’t after all be necessary, just yet. Naturally we will continue to check the PSA regularly in case it goes up, but I’m assured these readings indicate ‘undetectable’ levels of the antigen, and suggest a healthily efficient and active immune system on my part.

I feel that with the help of an able, friendly and wonderfully proficient team I have really dodged a bullet here. The aggressive nature and rate of the carcinoma suggests that had I left it unattended I might well have been presented with serious issues. As it is, I feel very, very, very lucky and privileged. There are a few things I can add. Yes, I have private insurance and was able to avail myself of the extra advantages in terms of privacy and speed that this can entail. However, most of the work Ben does is for the NHS, and I know that he gives precisely the same high levels of interpersonal care, consideration, and professionalism to all his patients. I know too that urology is more than just a speciality to him: it is a calling. His and Roger’s work for The Urology Foundation and their passionate advocacy for more awareness and public health prioritization in the field speaks for itself, and I am happy to do what I can to help them raise awareness of prostate cancer in men and their families.

I will never be able to express the full depth of my gratitude to Tony, Roger, Ben, and the team of nurses at the Princess Grace and the Prostate Centre who made the short, swift journey so relatively easy and comfortable. If I never see an incontinence pad, Steri Strip, stoma, or catheter bag again in my life, that will be too soon.

References

BBC News. ‘Fry and Turnbull effect’ on prostate cancer. BBC https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-45795337 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Related links

Squeezy: https://apps.beta.nhs.uk/squeezy-for-men/

Urology Foundation: https://www.theurologyfoundation.org/get-involved

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fry, S., Challacombe, B. Both sides of the scalpel: the patient and the surgeon view. Nat Rev Urol 16, 153–158 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-019-0153-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-019-0153-y