Abstract

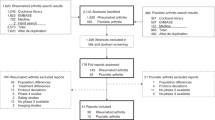

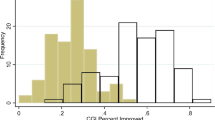

Nocebo effects are noxious reactions to therapeutic interventions that occur because of negative expectations of the patient. In the past decade, neurobiological data have revealed specific neural pathways induced by nocebos (that is, interventions that cause nocebo effects), as well as the associated mechanisms and predisposing factors of nocebo effects. Epidemiological data suggest that nocebos can have a notable effect on medication adherence, clinical outcomes and health-care policy. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) indicate that withdrawal of treatment by placebo-arm participants owing to adverse events is common; a proportion of these events could be nocebo effects. Moreover, in large-scale, open-label studies of patients with RMDs who transition from bio-originator to biosimilar therapeutics, biosimilar retention rates were much lower than in previous double-blind switch RCTs. This discrepancy suggests that in addition to the lack of response in some patients because of intrinsic differences between the drugs, nocebos might have an important role in low biosimilar retention, thus increasing the need for awareness and early identification of nocebo effects by rheumatologists and allied health-care professionals.

Key points

-

Nocebo effects are noxious changes in a patient’s symptoms or physiological condition that occur because of the patient’s negative anticipation of treatment, and might result in suboptimal outcomes and non-adherence.

-

Nocebo effects are observed in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, and might hinder the transition of patients to biosimilars.

-

Physicians should be aware of the risk factors for nocebo effects, which can be categorized as features relating to the patient, physician, disease, health-care setting or drug.

-

Physicians should make efforts to measure, prevent and address nocebo effects in clinical practice and interventional trials.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Benedetti, F., Lanotte, M., Lopiano, L. & Colloca, L. When words are painful: unraveling the mechanisms of the nocebo effect. Neuroscience 147, 260–271 (2007).

Grimes, D. A. & Schulz, K. F. Nonspecific side effects of oral contraceptives: nocebo or noise? Contraception 83, 5–9 (2011).

Gupta, A. et al. Adverse events associated with unblinded, but not with blinded, statin therapy in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial and its non-randomised non-blind extension phase. Lancet 389, 2473–2481 (2017).

Mitsikostas, D. D. Nocebo in headaches: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 12, 132–137 (2012).

Schedlowski, M., Enck, P., Rief, W. & Bingel, U. Neuro-bio-behavioral mechanisms of placebo and nocebo responses: implications for clinical trials and clinical practice. Pharmacol. Rev. 67, 697–730 (2015).

Feys, F., Bekkering, G. E., Singh, K. & Devroey, D. Do randomized clinical trials with inadequate blinding report enhanced placebo effects for intervention groups and nocebo effects for placebo groups? Syst. Rev. 3, 14 (2014).

Colloca, L. & Miller, F. G. The nocebo effect and its relevance for clinical practice. Psychosomat. Med. 73, 598–603 (2011).

Hadler, N. M. If you have to prove you are ill, you can’t get well. The object lesson of fibromyalgia. Spine 21, 2397–2400 (1996).

Arnold, M. H., Finniss, D. G. & Kerridge, I. Medicine’s inconvenient truth: the placebo and nocebo effect. Internal Med. J. 44, 398–405 (2014).

Ashraf, B., Saaiq, M. & Zaman, K. U. Qualitative study of nocebo phenomenon (NP) involved in doctor-patient communication. Int. J. Health Policy Management 3, 23–27 (2014).

Chavarria, V. et al. The placebo and nocebo phenomena: their clinical management and impact on treatment outcomes. Clin. Ther. 39, 477–486 (2017).

Colloca, L. & Finniss, D. Nocebo effects, patient-clinician communication, and therapeutic outcomes. JAMA 307, 567–568 (2012).

Drici, M. D., Raybaud, F., De Lunardo, C., Iacono, P. & Gustovic, P. Influence of the behaviour pattern on the nocebo response of healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 39, 204–206 (1995).

Palermo, S., Benedetti, F., Costa, T. & Amanzio, M. Pain anticipation: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of brain imaging studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 1648–1661 (2015).

LaBar, K. S., Gatenby, J. C., Gore, J. C., LeDoux, J. E. & Phelps, E. A. Human amygdala activation during conditioned fear acquisition and extinction: a mixed-trial fMRI study. Neuron 20, 937–945 (1998).

Jensen, K. B. et al. A neural mechanism for nonconscious activation of conditioned placebo and nocebo responses. Cereb. Cortex 25, 3903–3910 (2015).

Kong, J. et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study on the neural mechanisms of hyperalgesic nocebo effect. J. Neurosci. 28, 13354–13362 (2008).

Schmid, J. et al. Neural underpinnings of nocebo hyperalgesia in visceral pain: a fMRI study in healthy volunteers. NeuroImage 120, 114–122 (2015).

Tinnermann, A., Geuter, S., Sprenger, C., Finsterbusch, J. & Buchel, C. Interactions between brain and spinal cord mediate value effects in nocebo hyperalgesia. Science 358, 105–108 (2017).

Devinsky, O., Morrell, M. J. & Vogt, B. A. Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain 118, 279–306 (1995).

Apkarian, A. V., Bushnell, M. C., Treede, R. D. & Zubieta, J. K. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur. J. Pain 9, 463–484 (2005).

Gwilym, S. E. et al. Psychophysical and functional imaging evidence supporting the presence of central sensitization in a cohort of osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 61, 1226–1234 (2009).

Freeman, S. et al. Distinct neural representations of placebo and nocebo effects. NeuroImage 112, 197–207 (2015).

Tracey, I. Getting the pain you expect: mechanisms of placebo, nocebo and reappraisal effects in humans. Nature Med. 16, 1277–1283 (2010).

Benedetti, F., Amanzio, M. & Maggi, G. Potentiation of placebo analgesia by proglumide. Lancet 346, 1231 (1995).

Benedetti, F., Amanzio, M. & Thoen, W. Disruption of opioid-induced placebo responses by activation of cholecystokinin type-2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 213, 791–797 (2011).

Jensen, J. et al. Separate brain regions code for salience versus valence during reward prediction in humans. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28, 294–302 (2007).

Scott, D. J. et al. Individual differences in reward responding explain placebo-induced expectations and effects. Neuron 55, 325–336 (2007).

Baliki, M. N., Geha, P. Y., Fields, H. L. & Apkarian, A. V. Predicting value of pain and analgesia: nucleus accumbens response to noxious stimuli changes in the presence of chronic pain. Neuron 66, 149–160 (2010).

Baliki, M., Katz, J., Chialvo, D. R. & Apkarian, A. V. Single subject pharmacological-MRI (phMRI) study: modulation of brain activity of psoriatic arthritis pain by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Mol. Pain 1, 32 (2005).

Benedetti, F., Durando, J. & Vighetti, S. Nocebo and placebo modulation of hypobaric hypoxia headache involves the cyclooxygenase-prostaglandins pathway. Pain 155, 921–928 (2014).

Baliki, M. N. & Apkarian Nociception, A. V. Pain, negative moods, and behavior selection. Neuron 87, 474–491 (2015).

Ren, W. et al. The indirect pathway of the nucleus accumbens shell amplifies neuropathic pain. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 220–222 (2016).

Rodriguez-Raecke, R. et al. Insular cortex activity is associated with effects of negative expectation on nociceptive long-term habituation. J. Neurosci. 30, 11363–11368 (2010).

Amanzio, M., Benedetti, F., Porro, C. A., Palermo, S. & Cauda, F. Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of brain correlates of placebo analgesia in human experimental pain. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 738–752 (2013).

Blasini, M., Corsi, N., Klinger, R. & Colloca, L. Nocebo and pain: an overview of the psychoneurobiological mechanisms. Pain Rep. 2, e585 (2017).

Colloca, L. & Benedetti, F. Placebo analgesia induced by social observational learning. Pain 144, 28–34 (2009).

Colloca, L., Sigaudo, M. & Benedetti, F. The role of learning in nocebo and placebo effects. Pain 136, 211–218 (2008).

Potvin, S. & Marchand, S. Pain facilitation and pain inhibition during conditioned pain modulation in fibromyalgia and in healthy controls. Pain 157, 1704–1710 (2016).

van Laarhoven, A. I. et al. Induction of nocebo and placebo effects on itch and pain by verbal suggestions. Pain 152, 1486–1494 (2011).

Rossettini, G., Carlino, E. & Testa, M. Clinical relevance of contextual factors as triggers of placebo and nocebo effects in musculoskeletal pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19, 27 (2018).

Colloca, L. & Benedetti, F. Nocebo hyperalgesia: how anxiety is turned into pain. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 20, 435–439 (2007).

Hauser, W., Sarzi-Puttini, P., Tolle, T. R. & Wolfe, F. Placebo and nocebo responses in randomised controlled trials of drugs applying for approval for fibromyalgia syndrome treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 30 (Suppl. 74), 78–87 (2012).

Colloca, L., Lopiano, L., Lanotte, M. & Benedetti, F. Overt versus covert treatment for pain, anxiety, and Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 3, 679–684 (2004).

Mitsikostas, D. D., Chalarakis, N. G., Mantonakis, L. I., Delicha, E. M. & Sfikakis, P. P. Nocebo in fibromyalgia: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled clinical trials and implications for practice. Eur. J. Neurol. 19, 672–680 (2012).

Vambheim, S. M. & Flaten, M. A. A systematic review of sex differences in the placebo and the nocebo effect. J. Pain Res. 10, 1831–1839 (2017).

Klosterhalfen, S. et al. Gender and the nocebo response following conditioning and expectancy. J. Psychosomat. Res. 66, 323–328 (2009).

Wendt, L. et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism is associated with somatosensory amplification and nocebo responses. PLoS ONE 9, e107665 (2014).

Amanzio, M., Palermo, S., Skyt, I. & Vase, L. Lessons learned from nocebo effects in clinical trials for pain conditions and neurodegenerative disorders. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 36, 475–482 (2016).

Rojas-Mirquez, J. C. et al. Nocebo effect in randomized clinical trials of antidepressants in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 375 (2014).

Amanzio, M. et al. Unawareness of deficits in Alzheimer’s disease: role of the cingulate cortex. Brain 134, 1061–1076 (2011).

Benedetti, F. et al. Loss of expectation-related mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease makes analgesic therapies less effective. Pain 121, 133–144 (2006).

Klinger, R., Blasini, M., Schmitz, J. & Colloca, L. Nocebo effects in clinical studies: hints for pain therapy. Pain Rep. 2, e586 (2017).

Barsky, A. J. et al. Somatic style and symptom reporting in rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosomatics 40, 396–403 (1999).

Barsky, A. J., Saintfort, R., Rogers, M. P. & Borus, J. F. Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon. JAMA 287, 622–627 (2002).

Corsi, N., Emadi Andani, M., Tinazzi, M. & Fiorio, M. Changes in perception of treatment efficacy are associated to the magnitude of the nocebo effect and to personality traits. Sci. Rep. 6, 30671 (2016).

Geers, A. L., Helfer, S. G., Weiland, P. E. & Kosbab, K. Expectations and placebo response: a laboratory investigation into the role of somatic focus. J. Behav. Med. 29, 171–178 (2006).

Nestoriuc, Y., Orav, E. J., Liang, M. H., Horne, R. & Barsky, A. J. Prediction of nonspecific side effects in rheumatoid arthritis patients by beliefs about medicines. Arthritis Care Res. 62, 791–799 (2010).

Crichton, F. & Petrie, K. J. Accentuate the positive: counteracting psychogenic responses to media health messages in the age of the Internet. J. Psychosomat. Res. 79, 185–189 (2015).

Khan, S., Holbrook, A. & Shah, B. R. Does googling lead to statin intolerance? Int. J. Cardiol. 262, 25–27 (2018).

Tausczik, Y., Faasse, K., Pennebaker, J. W. & Petrie, K. J. Public anxiety and information seeking following the H1N1 outbreak: blogs, newspaper articles, and Wikipedia visits. Health Commun. 27, 179–185 (2012).

Faasse, K., Gamble, G., Cundy, T. & Petrie, K. J. Impact of television coverage on the number and type of symptoms reported during a health scare: a retrospective pre-post observational study. BMJ Open 2, e001607 (2012).

Amanzio, M., Corazzini, L. L., Vase, L. & Benedetti, F. A systematic review of adverse events in placebo groups of anti-migraine clinical trials. Pain 146, 261–269 (2009).

Mitsikostas, D. D., Mantonakis, L. I. & Chalarakis, N. G. Nocebo is the enemy, not placebo. A meta-analysis of reported side effects after placebo treatment in headaches. Cephalalgia 31, 550–561 (2011).

Howick, J. Saying things the “right” way: avoiding “nocebo” effects and providing full informed consent. Am. J. Bioeth 12, 33–34 (2012).

Bartels, D. J. P. et al. Minimizing nocebo effects by conditioning with verbal suggestion: a randomized clinical trial in healthy humans. PLoS ONE 12, e0182959 (2017).

Mancini, F., Beaumont, A. L., Hu, L., Haggard, P. & Iannetti, G. D. Touch inhibits subcortical and cortical nociceptive responses. Pain 156, 1936–1944 (2015).

Tweehuysen, L. et al. Open-label non-mandatory transitioning from originator etanercept to biosimilar SB4: 6-month results from a controlled cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 70, 1408–1418 (2018).

Vogtle, E., Barke, A. & Kroner-Herwig, B. Nocebo hyperalgesia induced by social observational learning. Pain 154, 1427–1433 (2013).

Planes, S., Villier, C. & Mallaret, M. The nocebo effect of drugs. Pharmacol. Res. Persp. 4, e00208 (2016).

Kong, J. & Benedetti, F. Placebo and nocebo effects: an introduction to psychological and biological mechanisms. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 225, 3–15 (2014).

Colgan, S. et al. Perceptions of generic medication in the general population, doctors and pharmacists: a systematic review. BMJ Open 5, e008915 (2015).

Weissenfeld, J., Stock, S., Lungen, M. & Gerber, A. The nocebo effect: a reason for patients’ non-adherence to generic substitution? Die Pharmazie 65, 451–456 (2010).

Branthwaite, A. & Cooper, P. Analgesic effects of branding in treatment of headaches. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed) 282, 1576–1578 (1981).

Faasse, K., Cundy, T., Gamble, G. & Petrie, K. J. The effect of an apparent change to a branded or generic medication on drug effectiveness and side effects. Psychosomat. Med. 75, 90–96 (2013).

Wells, G. et al. Validation of the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68, 954–960 (2009).

Garrett, S. et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J. Rheumatol. 21, 2286–2291 (1994).

Park, W. et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 compared with maintenance of CT-P13 in ankylosing spondylitis: 102-week data from the PLANETAS extension study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 346–354 (2017).

Yoo, D. H. et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 and continuing CT-P13 in the PLANETRA extension study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 355–363 (2017).

Zou, K. et al. Examination of overall treatment effect and the proportion attributable to contextual effect in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1964–1970 (2016).

Mitsikostas, D. D. Nocebo in headache. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 29, 331–336 (2016).

Galvez-Sanchez, C. M., Reyes Del Paso, G. A. & Duschek, S. Cognitive impairments in fibromyalgia syndrome: associations with positive and negative affect, alexithymia, pain catastrophizing and self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 9, 377 (2018).

Cepeda, M. S., Lobanov, V. & Berlin, J. A. Use of ClinicalTrials.gov to estimate condition-specific nocebo effects and other factors affecting outcomes of analgesic trials. J. Pain 14, 405–411 (2013).

Javaid, M. K. et al. Individual magnetic resonance imaging and radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis in subjects with unilateral knee pain: the health, aging, and body composition study. Arthritis Rheum. 64, 3246–3255 (2012).

Dieppe, P., Goldingay, S. & Greville-Harris, M. The power and value of placebo and nocebo in painful osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 24, 1850–1857 (2016).

Schaible, H. G. Mechanisms of chronic pain in osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 14, 549–556 (2012).

Axford, J. et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis: use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool. Clin. Rheumatol 29, 1277–1283 (2010).

Zhang, W., Robertson, J., Jones, A. C., Dieppe, P. A. & Doherty, M. The placebo effect and its determinants in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, 1716–1723 (2008).

Bannuru, R. R. et al. Effectiveness and implications of alternative placebo treatments: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of osteoarthritis trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 163, 365–372 (2015).

Koog, Y. H., Lee, J. S. & Wi, H. Nonspecific adverse events in knee osteoarthritis clinical trials: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 9, e111776 (2014).

Hermans, L. et al. Influence of morphine and naloxone on pain modulation in rheumatoid arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome/fibromyalgia, and controls: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Pain Pract. 18, 418–430 (2017).

Neame, R. & Hammond, A. Beliefs about medications: a questionnaire survey of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 44, 762–767 (2005).

Keystone, E. et al. Safety and efficacy of additional courses of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label extension analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 56, 3896–3908 (2007).

Park, W. et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from innovator rituximab to biosimilar CT-P10 compared with continued treatment with CT-P10: results of a 56-week open-label study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BioDrugs 31, 369–377 (2017).

Tak, P. P. et al. Sustained inhibition of progressive joint damage with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year results from the randomised controlled trial IMAGE. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71, 351–357 (2012).

Cepeda, M. S., Lobanov, V. & Berlin, J. A. Using Sherlock and ClinicalTrials.gov data to understand nocebo effects and adverse event dropout rates in the placebo arm. J. Pain 14, 999 (2013).

Dorner, T. & Kay, J. Biosimilars in rheumatology: current perspectives and lessons learnt. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 11, 713–724 (2015).

Choe, J. Y. et al. A randomised, double-blind, phase III study comparing SB2, an infliximab biosimilar, to the infliximab reference product Remicade in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 58–64 (2017).

Cohen, S. et al. A phase I pharmacokinetics trial comparing PF-05280586 (a potential biosimilar) and rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 82, 129–138 (2016).

Cohen, S. et al. Efficacy and safety of the biosimilar ABP 501 compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, phase III equivalence study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1679–1687 (2017).

Emery, P. et al. A phase III randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study comparing SB4 with etanercept reference product in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 51–57 (2017).

Girolomoni, G. et al. Comparison of injection-site reactions between the etanercept biosimilar SB4 and the reference etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis from a phase III study. Br. J. Dermatol. 178, e215–e216 (2018).

Glintborg, B. et al. Drug concentrations and anti-drug antibodies during treatment with biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) in routine care. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 47, 418–421 (2018).

Matsuno, H. et al. Phase III, multicentre, double-blind, randomised, parallel-group study to evaluate the similarities between LBEC0101 and etanercept reference product in terms of efficacy and safety in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis inadequately responding to methotrexate. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 488–494 (2018).

Morita, J. et al. Pharmacokinetic bioequivalence, safety, and immunogenicity of DMB-3111, a trastuzumab biosimilar, and trastuzumab in healthy Japanese adult males: results of a randomized trial. BioDrugs 30, 17–25 (2016).

Weinblatt, M. E. et al. Phase III randomized study of SB5, an adalimumab biosimilar, versus reference adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 70, 40–48 (2018).

Yoo, D. H. et al. A phase III randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with reference infliximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: 54-week results from the PLANETRA study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 18, 82 (2016).

Yoo, D. H. et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial to compare the pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety of CT-P10 and innovator rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 566–570 (2017).

Avouac, J. et al. Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: The experience of Cochin University Hospital, Paris, France. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 47, 741–748 (2018).

Boone, N. W. et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74, 655–661 (2018).

Glintborg, B. et al. A nationwide non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 802 patients with inflammatory arthritis: 1-year clinical outcomes from the DANBIO registry. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1426–1431 (2017).

Rezk, M. F. & Pieper, B. Treatment outcomes with biosimilars: be aware of the nocebo effect. Rheumatol. Ther. 4, 209–218 (2017).

Scherlinger, M. et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in real-life: the weight of patient acceptance. Joint Bone Spine 85, 561–567 (2017).

Tweehuysen, L. et al. Subjective complaints as the main reason for biosimilar discontinuation after open-label transition from reference infliximab to biosimilar infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 70, 60–68 (2018).

Cohen, H. et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv. Ther. 33, 2160–2172 (2017).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L., Lonnfors, S., Roblin, X., Danese, S. & Avedano, L. Patient perspectives on biosimilars: a survey by the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations. J. Crohns Colitis 11, 128–133 (2017).

Jorgensen, K. K. et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 389, 2304–2316 (2017).

Smolen, J. S. et al. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy after switching from reference infliximab to biosimilar SB2 compared with continuing reference infliximab and SB2 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a randomised, double-blind, phase III transition study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 234–240 (2018).

Gentileschi, S. et al. Switch from infliximab to infliximab biosimilar: efficacy and safety in a cohort of patients with different rheumatic diseases. Response to: Nikiphorou E, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of CT-P13 (Infliximab biosimilar) used as a switch from Remicade (infliximab) in patients with established rheumatic disease. Report of clinical experience based on prospective observational data. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1677–1683. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 16, 1311–1312 (2015).

Nikiphorou, E. et al. Clinical effectiveness of CT-P13 (Infliximab biosimilar) used as a switch from Remicade (infliximab) in patients with established rheumatic disease. Report of clinical experience based on prospective observational data. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 15, 1677–1683 (2015).

Tanaka, Y. et al. Safety and efficacy of CT-P13 in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis in an extension phase or after switching from infliximab. Mod. Rheumatol. 27, 237–245 (2017).

Scherlinger, M., Langlois, E., Germain, V. & Schaeverbeke, T. Acceptance rate and sociological factors involved in the switch from originator to biosimilar etanercept (SB4). Semin. Arthritis Rheum. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.07.005 (2018).

Desai, R. J. et al. Differences in rates of switchbacks after switching from branded to authorized generic and branded to generic drug products: cohort study. BMJ 361, k1180 (2018).

Ringe, J. D. & Moller, G. Differences in persistence, safety and efficacy of generic and original branded once weekly bisphosphonates in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis: 1-year results of a retrospective patient chart review analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 30, 213–221 (2009).

Faasse, K., Cundy, T. & Petrie, K. J. Medicine and the media. Thyroxine: anatomy of a health scare. BMJ 339, b5613 (2009).

Rief, W. et al. Preoperative optimization of patient expectations improves long-term outcome in heart surgery patients: results of the randomized controlled PSY-HEART trial. BMC Med. 15, 4 (2017).

Mitsikostas, D. D. & Deligianni, C. I. Q-No: a questionnaire to predict nocebo in outpatients seeking neurological consultation. Neurol. Sci. 36, 379–381 (2015).

Younger, J., Gandhi, V., Hubbard, E. & Mackey, S. Development of the Stanford Expectations of Treatment Scale (SETS): a tool for measuring patient outcome expectancy in clinical trials. Clin. Trials 9, 767–776 (2012).

Greco, C. M. et al. Measuring nonspecific factors in treatment: item banks that assess the healthcare experience and attitudes from the patient’s perspective. Qual. Life Res. 25, 1625–1634 (2016).

Colagiuri, B. & Quinn, V. F. Autonomic arousal as a mechanism of the persistence of nocebo hyperalgesia. J. Pain 19, 476–486 (2017).

Wells, R. E. & Kaptchuk, T. J. To tell the truth, the whole truth, may do patients harm: the problem of the nocebo effect for informed consent. Am. J. Bioeth. 12, 22–29 (2012).

Colloca, L. Nocebo effects can make you feel pain. Science 358, 44 (2017).

Kaptchuk, T. J. et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 336, 999–1003 (2008).

Rief, W., Bingel, U., Schedlowski, M. & Enck, P. Mechanisms involved in placebo and nocebo responses and implications for drug trials. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 90, 722–726 (2011).

Bingel, U. Avoiding nocebo effects to optimize treatment outcome. JAMA 312, 693–694 (2014).

Horne, R. et al. The perceived sensitivity to medicines (PSM) scale: an evaluation of validity and reliability. Br. J. Health Psychol. 18, 18–30 (2013).

Kay, J. et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the use of biosimilars to treat rheumatological diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 165–174 (2018).

van de Putte, L. B. et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab as monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis for whom previous disease modifying antirheumatic drug treatment has failed. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, 508–516 (2004).

Gordon, K. B. et al. Clinical response to adalimumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: double-blind, randomized controlled trial and open-label extension study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 55, 598–606 (2006).

Chaudhari, U. et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet 357, 1842–1847 (2001).

van der Heijde, D. et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum. 52, 582–591 (2005).

Gottlieb, A. B. et al. A randomized trial of etanercept as monotherapy for psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol. 139, 1627–1632 (2003).

Emery, P. et al. Sustained remission with etanercept tapering in early rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1781–1792 (2014).

Wechsler, M. E. et al. Mepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 1921–1932 (2017).

Tony, H. P. et al. Comparison of switching from the originator rituximab to the biosimilar rituximab GP2013 or re-treatment with the originator rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: safety and immunogenicity results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69 (Suppl. 10), 2795 (2017).

Cohen, S. B. et al. An extension study of PF-05280586, a potential rituximab biosimilar, versus rituximab in subjects with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23586 (2018).

Weinblatt, M. E. et al. Switching from reference adalimumab to SB5 (adalimumab biosimilar) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: fifty-two-week phase III randomized study results. Arthritis Rheumatol. 70, 832–840 (2018).

Emery, P. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis continuing on SB4 or switching from reference etanercept to SB4. Ann. Rheum. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211591 (2017).

Glintborg, B. et al. One-year clinical outcomes in 1623 patients with inflammatory arthritis who switched from originator to biosimilar etanercept – an observational study from the Danish Danbio Registry [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69 (Suppl. 10), 1550 (2017).

Abdalla, A. et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of biosimilar infliximab among patients with inflammatory arthritis switched from reference product. Open Access Rheumatol. 9, 29–35 (2017).

Benucci, M. et al. Safety, efficacy and immunogenicity of switching from innovator to biosimilar infliximab in patients with spondyloarthritis: a 6-month real-life observational study. Immunol. Res. 65, 419–422 (2017).

Forejtová, Š. et al. Non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 36 patients with ankylosing spondylitis: 6 – months clinical outcomes from the Czech Biologic Registry ATTRA [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69 (Suppl. 10), 1549 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Rheumatology thanks J. Kay, R. Fleischmann, S. Palerma and U. Bingel for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.K. declares no competing interests. D.D.M has received honoraria and/or research and travel grants and/or consultation fees from Allegra, Amgen, Biogen, Cephaly, Electrocore, Elli Lilly, Merck-Serono, Merz, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi and Teva. G.D.K has received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards and/or support for the organization of educational meetings and/or attendance to congresses from Abbvie, Aenorasis, BMS, Genesis, GSK, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer and UCB. P.P.S. has received honoraria for lectures and/or advisory boards and/or funding for research and congress attendances from Abbvie, Aenorasis, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer, Elli Lilly, Elpen, Genesis, Jannsen, Pfizer, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi and UCB.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Glossary

- Nocebo

-

The word nocebo is derived from the Latin word noceo (‘to harm’) and is the opposite of placebo; nocebo denotes a medical intervention that causes adverse events owing to negative expectations of the patient, and can include inert substances or medications, medical procedures or patient–physician encounters.

- Nocebo effects

-

Noxious changes in a patient’s symptoms or physiologic condition caused by a nocebo; nocebo effects can result in suboptimal outcomes and non-adherence.

- Placebo

-

The word placebo is derived from the latin term placeo (“I shall please”) and denotes a medical intervention that induces beneficial effects owing to positive expectations of the patient.

- Nocebo response

-

A neurobiological alteration of the brain–body unit that is not directly attributable to a drug’s pharmacokinetics and might cause a negative treatment outcome.

- Placebo effect

-

An improvement in a patient’s symptoms or physiologic condition resulting from a placebo.

- Placebo response

-

A positive treatment outcome caused by a placebo manipulation; the placebo response reflects the neurobiological and psychophysiological response of an individual to an inert substance or sham treatment and is mediated by various factors within the treatment context.

- Hyperalgesia

-

An increased sensitivity to pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kravvariti, E., Kitas, G.D., Mitsikostas, D.D. et al. Nocebos in rheumatology: emerging concepts and their implications for clinical practice. Nat Rev Rheumatol 14, 727–740 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-018-0110-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-018-0110-9

This article is cited by

-

Maximizing the success of biosimilar implementation

Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2023)

-

Real-world experience of rituximab biosimilar GP2013 in rheumatoid arthritis patients naïve to or switched from reference rituximab

Rheumatology International (2023)

-

Outcomes Following Adalimumab Bio-originator to Biosimilar Switch—A Comparison Using Real-world Patient- and Physician-Reported Data in European Countries

Rheumatology and Therapy (2023)

-

The PROPER Study: A 48-Week, Pan-European, Real-World Study of Biosimilar SB5 Following Transition from Reference Adalimumab in Patients with Immune‐Mediated Inflammatory Disease

BioDrugs (2023)

-

Meta-analysis of placebo-arm dropouts in osteoporosis randomized-controlled trials and implications for nocebo-associated discontinuation of anti-osteoporotic drugs in clinical practice

Osteoporosis International (2023)