Abstract

Over the past decade, a genomics revolution, made possible through the development of high-throughput sequencing, has triggered considerable progress in the study of ancient DNA, enabling complete genomes of past organisms to be reconstructed. A newly established branch of this field, ancient pathogen genomics, affords an in-depth view of microbial evolution by providing a molecular fossil record for a number of human-associated pathogens. Recent accomplishments include the confident identification of causative agents from past pandemics, the discovery of microbial lineages that are now extinct, the extrapolation of past emergence events on a chronological scale and the characterization of long-term evolutionary history of microorganisms that remain relevant to public health today. In this Review, we discuss methodological advancements, persistent challenges and novel revelations gained through the study of ancient pathogen genomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The long shared history between humans and infectious disease places ancient pathogen genomics within the interest of several fields such as microbiology, evolutionary biology, history and anthropology. Research on this topic aims to better understand the interactions between pathogens and their hosts on an evolutionary timescale, to uncover the origins of pathogens and to disentangle the genetic processes involved in their epidemic emergence among human populations. Over the past 10,000 years, major transitions in human subsistence strategies, such as those that accompanied the Neolithic revolution1, likely exposed our species to a novel range of infectious agents2. Closer contact with domesticated animals would have increased the frequency of zoonotic transmission events, and higher human population densities would have enhanced the potential of pathogens to propagate within and between groups. Throughout human history, a number of epidemics and pandemics have been recorded or are hypothesized to have occurred (Fig. 1). Although most of their causative agents still remain speculative, robust molecular methods coupled with archaeological and historical data can confidently demonstrate the involvement of certain pathogens in these episodes.

This overview provides a timeline of key events in predominantly Eurasian history since the Neolithic period (upper panel, grey squares), which have overlapped temporally and geographically with major historical epidemics or pandemics (lower panel, beige squares). The respective citations are indicated, in which whole-genome or low-coverage genome-wide data from pathogens implicated in those events have been reconstructed by ancient DNA analysis. B19V, human parvovirus B19; bce, before current era; ce, current era; HBV, hepatitis B virus; H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; Y. pestis, Yersinia pestis.

The investigation of past infectious diseases has traditionally been conducted through palaeopathological assessment of ancient skeletal assemblages3,4, although this approach is limited by the fact that most acute infections do not leave visible traces on bone. Since the 1990s, the field of ancient DNA (aDNA) has brought molecular techniques to this study, providing a diachronic genetic perspective to infectious disease research. Initial attempts relied on PCR technology5,6,7,8,9, which restricted the study of ancient microbial DNA to targeted, short genomic fragments that were amplified from ancient human remains. This method made infectious disease detection possible but gave limited information on the evolutionary history of the pathogen. In addition, complications associated with the study of aDNA, which is typically present at low quantities, is heavily fragmented and harbours chemical modifications10,11,12, hampered efforts to reproduce and authenticate early findings13,14,15.

Over the past decade, major advancements in genomics, in particular, the development of high-throughput sequencing, also called next-generation sequencing (NGS)16, radically increased the amount of data that can be retrieved from ancient remains. This technology has assisted the development of quantitative methods for aDNA authentication11,12,17,18,19 and has enabled the retrieval of whole ancient pathogen genomes from archaeological specimens. The first such genome, published in 2011 (ref.20), was that of the notorious bacterial pathogen Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Since then, the field has expanded its directions to the in-depth study of infectious disease evolution, providing a unique resource for understanding human history.

Here, we review the latest methodological innovations that have aided the whole-genome retrieval and evolutionary analysis of various ancient pathogens (Table 1), most of which are still relevant to public health today. In the second half of this Review, we highlight the utility of this approach by discussing evolutionary events in the history of Y. pestis that have been uniquely revealed through the study of ancient genomes.

Methods for isolating ancient microbial DNA

The sweet spot for ancient pathogen DNA

The retrieval of DNA from ancient human, animal or plant remains carries with it a number of challenges, namely, its limited preservation and hence low abundance, its highly fragmented and damaged state and the pervasive modern-DNA contamination that necessitates a confident evaluation of its authenticity21,22. Efficient aDNA recovery is best accomplished via sampling of the anatomical element that contains the highest quantity of DNA from the target organism. For human aDNA analysis, bone and teeth have been the preferred study material, given their abundance in the archaeological record. Recent studies suggest that the inner-ear portion of the petrous bone23 and the cementum layer of teeth24 have the greatest potential for successful human DNA retrieval. However, petrous bone sampling and shotgun NGS sequencing of aDNA from five Bronze Age skeletons previously shown to be carrying Y. pestis failed to detect the bacterium in this source material, suggesting that its preservation potential for pathogen DNA is low25.

Direct sampling from skeletal lesions, where present, has proved a rich source of aDNA for some chronic disease-causing bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which was isolated from vertebrae26; Mycobacterium leprae, which could be isolated from portions of the maxilla and various long bones27,28; and Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum and T. pallidum subsp. pertenue, which have been isolated from long bones29. Of note, the sampling methods for recovering pathogen DNA do not generally follow a standardized procedure, in part because of the great diversity in tissue tropism and resulting disease progression. In addition, acute blood-borne infections do not typically produce diagnostic bone changes as opposed to those that affect their hosts chronically3. Therefore, if infections have caused mortality in the acute phase, as is the case for individuals from epidemic contexts who do not display skeletal evidence of infection, the preferred study material has been the inner cavities of teeth. Pathogen aDNA is thought to be preserved within the remnants of the pulp chamber, likely as part of desiccated blood8,17. Consequently, tooth sampling has proved successful in the retrieval of whole genomes or genome-wide data (that is, low-coverage genomes that have provided limited analytical resolution) from ancient bacteria such as Y. pestis20,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, Borrelia recurrentis40 and Salmonella enterica41; ancient eukaryotic pathogens such as Plasmodium falciparum42; and ancient viruses such as hepatitis B virus (HBV)43,44 and human parvovirus B19 (B19V)45. Even M. leprae, which commonly manifests in the chronic form, has been retrieved from ancient teeth27,28.

Other types of specimen have also shown potential for aDNA retrieval. Examples are dental calculus as a source of oral pathogens, such as Tannerella forsythia46; calcified nodules, which have yielded whole genomes from Brucella melitensis47, Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Gardnerella vaginalis48; mummified tissues, which have yielded Helicobacter pylori49, Variola virus (VARV; also known as smallpox)50,51, M. tuberculosis52 and HBV53,54; alcohol-preserved human tissue as a source for Vibrio cholerae DNA55; historical blood stains preserving P. falciparum and Plasmodium vivax56; frozen and formalin-fixed samples, yielding HIV57 and influenza virus58 RNA; and dried plant leaves from herbarium collections, preserving Phytophthora infestans59,60, the oomycete that caused the Irish potato famine.

Segregating the metagenomic soup: methods for pathogen detection

Regardless of the source of genetic material, most ancient specimens yield complex metagenomic data sets. Poorly preserved aDNA usually makes up a miniscule fraction of the total genetic material extracted from a sample (<1%), and the majority of DNA usually stems from organisms residing in the environment41. Hence, specialized protocols are necessary for the detection and isolation of ancient pathogen DNA and its confident segregation from a rich environmental DNA background (Fig. 2).

The diagram provides an overview of techniques used for pathogen DNA detection in ancient remains by distinguishing between laboratory and computational methods. In both cases, processing begins with the extraction of DNA from ancient specimens183. As part of the laboratory pipeline, direct screening of extracts can be performed by PCR (quantitative (qPCR) or conventional) against species-specific genes, as done previously17,61,63,64. PCR techniques alone, however, can suffer from frequent false-positive results and should therefore always be coupled with further verification methods such as downstream genome enrichment and/or next-generation sequencing (NGS) in order to ensure ancient DNA (aDNA) authentication of putatively positive samples. Alternatively, construction of NGS libraries184,185 has enabled pathogen screening via fluorescence-based detection on microarrays66 and via DNA enrichment approaches17. The latter has been achieved, through single locus in-solution capture26,28 or through simultaneous screening for multiple pathogens using microarray-based enrichment of species-specific loci65 and enables post-NGS aDNA authentication. In addition, data produced by direct (shotgun) sequencing of NGS libraries before enrichment can also be used for pathogen screening using computational tools. After pre-processing, reads can be directly mapped against a target reference genome (in cases for which contextual information is suggestive of a causative organism) or against a multigenome reference composed of closely related species to achieve increased mapping specificity of ancient reads. Alternatively, ancient pathogen DNA can also be detected using metagenomic profiling methods, as presented elsewhere41,71,72, through taxonomic assignment of shotgun NGS reads. Both approaches allow for subsequent assessment of aDNA authenticity and can be followed by whole pathogen genome retrieval through targeted enrichment or direct sequencing of positive sample libraries.

In this context, laboratory-based techniques are separated into those that target a specific microorganism and those that screen for several pathogenic microorganisms simultaneously (Fig. 2). Methods that screen for a single microorganism have used species-specific assays of conventional or quantitative PCR (also known as real-time PCR)17,61,62,63,64, as well as hybridization-based enrichment techniques17,26,28 (Fig. 2). These methods are particularly useful when the target microorganism is known, for example, in the presence of diagnostic skeletal lesions among the studied individuals26,28, or when a hypothesis exists for the causative agent of an epidemic17. By contrast, broad laboratory-based pathogen screening in aDNA research has used microarrays for both targeted enrichment65 and fluorescence-based detection66, whereby probes are designed to represent unique or conserved regions from a range of pathogenic bacteria, parasites or viruses. Although amplification-based or fluorescence-based approaches can be fast and cost-effective for screening large sample collections17,38, enrichment-based techniques are usually coupled with NGS and therefore provide data that can be used to assess aDNA authenticity.

When shotgun-sequencing data are generated, computational screening approaches can be used to detect the presence of pathogen DNA as well as for metagenomic profiling of ancient specimens (Fig. 2). In cases for which a causative agent is suspected, NGS reads can be directly mapped (for example, using the read alignment software Burrows–Wheeler aligner67) against a specific reference genome or against a multigenome reference that includes several species of a certain genus with the purpose of achieving a higher mapping specificity to the target organism34 (Fig. 2). In addition, broad approaches involve the use of metagenomic techniques for pathogen screening. Examples of tools that have shown their effectiveness with ancient metagenomic DNA include the widely used Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)68; the MEGAN Alignment Tool (MALT)41, which involves a taxonomic binning algorithm that can use whole-genome databases (such as the National Center for Biotechnical Information (NCBI) Reference Sequence (RefSeq) database69); Metagenomic Phylogenetic Analysis (MetaPhlAn)70, which is also integrated into the metagenomic pipeline MetaBIT71 and uses thousands (or millions) of marker genes for the distinction of specific microbial clades; or Kraken72, an alignment-free sequence classifier that is based on k-mer matching of a query to a constructed database.

Taxonomic sequence assignments from the above methods, however, should be interpreted with caution, mainly because some pathogenic microorganisms have close environmental relatives that are often insufficiently represented in public databases. For example, a >97% sequence identity was shown between environmental taxa and human-associated pathogens such as M. tuberculosis and Y. pestis according to an analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA genes73. As such, given that environmental DNA often dominates ancient remains that stem from burial contexts74, analyses should always ensure a qualitative assessment of assigned reads, that is, an evaluation of their mapping specificity and their genetic distance (also called edit distance) to the putatively detected organism. In addition, one should consider the known aDNA damage characteristics as criteria for data authenticity. Although several types of chemical damage can affect post-mortem DNA survival, certain characteristics have been more extensively quantified. The first, termed depurination, is a hydrolytic mechanism under which purine bases become excised from DNA strands. This process results in the formation of abasic sites and is a known contributor to the fragmentation patterns observed in aDNA. As such, an increased base frequency of A and G compared with C and T immediately preceding the 5ʹ ends of aDNA fragments is often considered a criterion for authenticity12. A second type of damage commonly identified among aDNA data sets is the hydrolytic deamination of C, whereby a C base is converted into U (and detected as its DNA analogue, T)12,75. This base modification usually occurs at single-stranded DNA overhangs that are most accessible to environmental insults, resulting in an increased frequency of miscoding lesions at the terminal ends of aDNA fragments11,12. Consequently, the evaluation of DNA damage profiles (for instance, by using mapDamage2.0 (ref.76)) is a prerequisite for authenticating ancient pathogen DNA and is necessary for ensuring aDNA data integrity in general. More detailed overviews of authentication criteria in ancient pathogen research have been reviewed elsewhere19,73.

Targeted enrichment approaches to isolate whole ancient pathogen genomes

Evolutionary relationships between past and present infectious agents are best determined through the use of whole-genome sequences of pathogens. However, the recovery of high-quality data is often challenging owing to the aforementioned characteristics of aDNA and therefore requires specialized sample processing. For example, in cases in which aDNA authenticity has already been achieved in the detection step, U residues resulting from post-mortem C deamination can be entirely77 or partially78 excised from aDNA molecules using the enzyme uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) to avoid their interference with downstream read mapping and variant calling.

In addition, given the low proportion of pathogen DNA in ancient remains, a common and cost-effective approach for whole-genome retrieval involves microarray-based or in-solution-based hybridization capture. Both methods constitute a form of genomic selection of continuous or discontinuous genomic regions through the design and use of single-stranded DNA or RNA probes that are complementary to the desired target. Microarray-based capture utilizes densely packed probes that are immobilized on a glass slide79. It is cost-effective in that it permits the parallel enrichment of molecules from several libraries that can be subsequently recovered through deep sequencing, although competition over the probes can impair enrichment efficiencies in specimens with comparatively lower target DNA contents. Nevertheless, this type of capture has shown its effectiveness in the recovery of both ancient pathogen and human DNA20,26,28,41,55,80.

More recently, in-solution-based capture approaches have gained popularity owing to their capacity for greater sample throughput without compromising capture efficiency81,82,83; every sample library can be captured individually, thus providing, in principle, an equal probe density per specimen. This technique has contributed to the increased number of specimens from which human genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data could be retrieved84,85, even from climate zones that pose challenges to aDNA preservation (presented elsewhere86,87,88). In addition, in-solution-based capture has recently become the preferred method for microbial pathogen genome recovery for both bacteria and DNA viruses (for examples, see refs34,37,41,43,45,49,50). Nevertheless, deep shotgun sequencing alone has also been used for human89,90,91 and pathogen28,33,48 high-quality genome reconstruction, especially for specimens with fairly high endogenous DNA yields, although this frequently carries with it a greater production cost.

Disentangling microbial evolution

Ancient pathogen genomes as molecular fossils

In the absence of ancient pathogen genomes, the timings of infectious disease emergence and early spread are inferred mainly through comparative genomics of modern pathogen diversity92,93, palaeopathological evaluation of ancient skeletal remains94 or analysis of historical records95,96. Such approaches are highly valuable and, when combined, can be used to build an interdisciplinary picture of infectious disease history; however, limitations also exist. For example, the analysis of contemporary pathogen genetic diversity considers only a short time depth of available data and cannot predict evolutionary scenarios that derive from lineages that are now extinct. In addition, skeletal markers of specific infections in past populations only exist for a few conditions and, when present, can rarely be considered as definitive, as numerous differential diagnoses can exist for a given skeletal pathology97. Similarly, historically recorded symptoms can often be misinterpreted given that past descriptions may be unspecific and do not always conform to modern medical terminology98.

In the past decade, the reconstruction of ancient pathogen genomes has complemented such analyses with direct molecular evidence, often revealing aspects of past infections that were unexpected on the basis of existing data. The recent identification of HBV DNA in a mummified individual showing a vesicopustular rash53, which is usually considered characteristic of infection with VARV, highlights the importance of molecular methods in evaluating differential diagnoses. The oldest recovered genomic evidence of HBV to date was from a 7,000-year-old individual from present-day Germany44, which shows that this pathogen has affected human populations since the Neolithic period. In addition, the virus was identified recently in human remains from the Bronze Age, Iron Age and up until the 16th century of the current era (ce) in Eurasia43,44,53,54.

Regarding bacterial pathogens, the identification of B. recurrentis in a 15th-century individual from Norway40 showed that — aside from Y. pestis — other vector-borne pathogens were also circulating in medieval Europe. Furthermore, the causative agents of syphilis and yaws, T. pallidum subsp. pallidum and T. pallidum subsp. pertenue, respectively, were recently identified in different individuals from colonial Mexico29 who exhibited similar skeletal lesions. This study demonstrates the power of ancient pathogen genomics in distinguishing past infectious disease agents that are genetically and phenotypically similar but that differ greatly in their public health significance. Finally, the identification of G. vaginalis and S. saprophyticus in calcified nodules from a woman’s remains (13th-century Troy)48 directly implicates these bacteria in pregnancy-related complications in the past. These findings, as well as other insights gained from analyses of ancient pathogen genomes (Table 1), demonstrate the ability of aDNA to contribute aspects of infectious disease history beyond those accessible by the palaeopathological, historical and modern genetic records.

Assessing within-species evolutionary relationships

The reconstruction of whole pathogen genomes has not only been a tool for demonstrating infectious disease presence in the past but also aided in the robust inference of microbial phylogeography, which is important for understanding the processes that influence pathogen distribution and diversity over time.

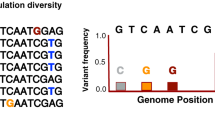

The evaluation of genetic relationships between ancient and modern pathogens is often conducted by direct whole-genome or genome-wide SNP comparisons of bacteria20,27,29,36,48, viruses43,44,50,53 or mitochondrial genomes and nuclear genome data from eukaryotic microorganisms56,59,60. Hence, accurate variant calling is critical for drawing reliable evolutionary inferences, although this process is often a challenge when handling data sets derived from samples with high rates of DNA fragmentation (resulting in ultrashort read data), low endogenous DNA content and high levels of DNA damage. In these cases, increased accuracy is best achieved through stringent NGS read mapping parameters and through visual inspection of the sequences overlapping the studied SNPs35. In addition, histograms of SNP allele frequencies — used to estimate the frequency of heterozygous calls in haploid organisms26,52 — can often demonstrate the effects of environmental contamination on ancient microbial data sets41.

Once variant calls are authenticated, one of the most common types of evolutionary inference in pathogen research is through phylogenetic analysis, which is a powerful means of resolving the genetic history of clonal microorganisms (Fig. 3). Among the most commonly used tools in ancient microbial genomics are MEGA99, which comprises several phylogenetic methods; PhyML100, RAxML101 and IQ-TREE102, which implement maximum-likelihood approaches; MrBayes103, which uses a Bayesian approach; and programs used for phylogenetic network inference, such as SplitsTree104. Two notable studies that examined phylogenetic relationships among ancient M. leprae genomes revealed a high strain diversity in Europe between the 5th and 14th centuries ce27,105. Considered alongside the oldest palaeopathological cases of leprosy dating to as early as the Copper and Bronze Age in Eurasia106,107 and the high frequency of protective immune variants against the disease identified in modern-day Europeans108, these results may suggest a long history of M. leprae presence in this region. Moreover, the phylogenetic analysis of a 12th-century S. enterica subsp. enterica genome from Europe showed its placement within the Paratyphi C lineage109. Further identification of the bacterium in 16th-century colonial Mexico41 revealed it as a previously unknown candidate pathogen that was likely introduced to the Americas through European contact. Given the low frequency of Paratyphi C today, these results may be indicative of a higher prevalence in past populations. Finally, an example from viral genomics is the recovery of HIV RNA from degraded serum specimens57, which highlighted the importance of archival collections in reconciling the expansion of recent pandemics. Specifically, these data were able to dispute a long-standing hypothesis regarding the initiation of HIV spread in the USA.

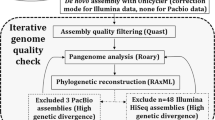

The diagram is an overview of whole-genome analysis applied to date for ancient microbial data sets and distinguishes the methods used for clonal and recombining pathogens; of note, the depicted summary is not meant to represent an exhaustive pipeline of all possible analyses that could be undertaken. Ancient genome reconstruction is usually initiated through reference-based mapping or through de novo assembly of the data, although the latter has only been possible in exceptional cases of ancient DNA (aDNA) preservation28,44. Subsequently, the genomes are assessed for their coverage depth and gene content for evaluation of their quality, which is also relevant for the comparative identification of virulence genes over their evolutionary time frames. Here, we show an example of virulence factor presence-or-absence analysis in the form of a heat map, as done previously33,34,37,41. In addition, a comparison of the ancient genome or genomes with modern genomes can be carried out for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) identification and for assessment of SNP effects (using SnpEff186), which is particularly relevant for variants that seem to be unique to the ancient genome or genomes. Initial evolutionary inference can often be carried out through phylogenetic analysis and by testing for possible evidence of recombination in the analysed data set, for example, by comparing the support of different phylogenetic topologies114 and by identifying potential recombination regions and homoplasies110,111. If the data support clonal evolution, robust phylogenetic inference (for example, through a maximum-likelihood approach) is followed by assessment of the temporal signal in the data124,125. If the data set shows a sufficient phylogenetic signal, molecular dating analysis and demographic modelling are considered possible, although the size of the data set will determine whether such analyses will be feasible and meaningful. Alternatively, if recombination is confirmed, genetic relationships between microbial clades or populations can be determined through phylogenetic network analysis104 or through the use of population genetic methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) and identification of ancestral admixture components112,113. In this case, the assessment of the temporal signal and proceeding with molecular dating analysis is cautioned and likely best performed after exclusion of recombination regions from all genomes in the data set. MRCA, most recent common ancestor. NGS, next-generation sequencing.

When the evolutionary histories of pathogens are influenced equally by mutation and recombination, additional tools have been used to identify recombining loci and to determine genetic relationships within and between microbial populations (Fig. 3). For example, the programs ClonalFrameML110 and Recombination Detection Program 4 (RDP4)111 have been used to infer potential recombination regions within ancient bacteria29,37 and viruses43,44,53, respectively. In addition, principal component analysis (PCA) and ancient admixture component estimation using the Bayesian modelling frameworks STRUCTURE112 and fineSTRUCTURE113 on both multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and whole-genome data were recently used for population assignment of a 5,300-year-old H. pylori genome49. These analyses revealed key information on changes of the bacterial population structure that occurred in Europe over time. Furthermore, the recent study of ancient T. pallidum subsp. pallidum and T. pallidum subsp. pertenue29 used the program TREE-PUZZLE114, a maximum-likelihood-based phylogenetic algorithm, to gain a more robust phylogenetic resolution of ambiguous branching patterns among bacterial lineages.

Such whole-genome analyses of both clonal and recombining pathogens have helped to elucidate not only past infectious disease phylogeography but also possible zoonotic or anthroponotic transmission events that reveal disease interaction networks through time. Among others (Table 1), a notable example is that of 1,000-year-old pre-Columbian M. tuberculosis genomes isolated from human remains, which showed a phylogenetic placement among animal-adapted lineages, being most closely related to a strain circulating in modern-day seals and sea lions26. Although the extent to which these strains were capable of human-to-human transmission is unclear, this study supports the existence of tuberculosis in pre-Columbian South America and is helping to delineate the genomic and adaptive history of M. tuberculosis in the region before European contact26. Another example of intriguing evolutionary relationships revealed uniquely through the study of ancient pathogen genomes includes analyses of Neolithic and Bronze Age HBV. These genomes grouped in extinct lineages that are most closely related to modern strains identified exclusively among African non-human primates43,44, a result that raises further questions regarding past transmission events in HBV history. Finally, the phylogenetic analysis of medieval M. leprae genomes suggested a European source for leprosy in the Americas28, reinforcing the hypothesis that humans passed the disease to the nine-banded armadillo, the most common reservoir for this disease in the New World115.

Importantly, the resolution of evolutionary analyses will depend on the quality, size and evenness of spatial sampling in the comparative data set. Therefore, the incomplete and often biased sampling of ancient and modern microbial strains can introduce challenges for discerning true biological relationships and past evolutionary events. Nevertheless, in recent years, marked reductions in NGS costs116 have aided the increased production of large whole-genome microbial data sets from present-day strains. Current efforts for centralized data repositories that are continuously curated (such as the Pathosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC) database117 and the recently introduced EnteroBase118) and the development of robust phylogenetic frameworks that can accommodate genome-wide data from >100,000 strains (for example, GrapeTree119) are becoming valuable for integrating large sample sizes into microbial evolutionary analyses. In combination with the increasing number of ancient microbial data sets, these tools will aid in the evaluation of genetic relationships by offering higher resolution.

Inferring divergence times through molecular dating

Apart from providing a molecular fossil record and revealing diachronic evolutionary relationships, a third analytical advantage gained from the retrieval of ancient pathogen genomes is that their ages can be directly used for calibration of a molecular clock. The ages of ancient specimens can be determined through contextual information, through archaeological artefacts or directly through radiocarbon dating, predominantly of bone or tooth collagen. Such temporal calibrations are required for high-accuracy estimations of microbial nucleotide substitution rates and in turn lineage divergence dates (Fig. 3), particularly because both estimations seem to be highly influenced by the time depth covered by the genomic data set120. For such analyses, the most widely used program is the Bayesian statistical framework BEAST121,122.

A characteristic example of how ancient calibration points can considerably affect divergence date estimates is that of M. tuberculosis. According to modern genetic data and human demographic events, the M. tuberculosis complex (MTBC) evolution was suggested to have followed human migrations out of Africa, with its emergence estimated at more than 70,000 years ago93. Recently, its emergence was re-estimated to a maximum of 6,000 years ago on the basis of the 1,000-year-old mycobacterial genomes from Peru26, a result that was further corroborated by the incorporation of 18th-century European MTBC genomes in the dating analysis26,52,123.

In molecular phylogenies, the length of each individual branch usually reflects the number of substitutions acquired by an organism within a given period of time and, as such, varying branch lengths should represent heterochronous sequences. Therefore, an important prerequisite for a robust dating analysis is that the nucleotide substitution rate of the species whose phylogeny is to be dated behaves in a ‘clock-like’ manner, meaning that phylogenetic branch lengths correlate with archaeological dates or sampling times. Such relationships can be assessed through date randomization and root-to-tip regression tests (Fig. 3). The former is used to assess the effect of arbitrary exchange of phylogenetic tip dates on the nucleotide substitution rate and divergence date estimates124, whereas the latter is used for estimation of a correlation coefficient (r) and coefficient of determination (R2) by relating the tip date of each taxon to its SNP distance from the tree root (using, for example, the program TempEst125). The resulting values determine whether there is a temporal signal in the data and suggest whether branches within a phylogeny evolve at a constant rate, in which case a strict molecular clock126 can be statistically tested, for example, using MEGA99 or marginal likelihood estimations127,128, and applied. If branches are affected by differences in their evolutionary rates, a relaxed clock129 would be more appropriate. In general, a constant molecular clock will rarely reliably describe the history of a microbial species, even more so for infectious pathogens whose replication rates vary between active and latent or between epidemic and dormant phases120,130. In certain cases, neither of the two models may fit the data, such as when extensive rate variation weakens the temporal signal. This challenge was encountered in initial attempts to date the Y. pestis phylogeny using too few ancient calibration points36,130. Similar limitations can arise when the evolutionary history of a microorganism is vastly affected by recombination, as observed for HBV44,53, although HBV molecular dating was recently attempted using a different genomic data set and suggested that the currently explored diversity of Old and New World primate lineages (including all human genotypes) may have emerged within the last 20,000 years43.

Molecular dating analysis requires the use of an appropriate demographic model for the available data, which can be determined through model-testing approaches (for example, through marginal likelihood estimations127,128). Currently, the most widely used models for estimating dates of divergence are the coalescent constant size131, which assumes a continuous population size history — and is unrealistic for epidemic pathogens — and the coalescent skyline132, which can estimate effective population size (Ne) changes over time. Moreover, the birth–death demographic model133,134, which is currently unexplored within aDNA frameworks, may prove an insightful analysis tool in the future. This model has shown its applicability on comprehensive pathogen data sets from modern-day epidemic contexts133. It has the ability to incorporate prior knowledge on incomplete sampling proportions and sampling biases within a data set, a frequent caveat of aDNA studies that is currently unaccounted for within molecular dating analyses. Finally, recently developed fast-dating algorithms should also be noted, for example, the least-squared dating (LSD) program, which does not use constrained demographic models but can handle uncorrelated rate variation among phylogenetic branches and has shown potential for analysing large genomic data sets135.

Yersinia pestis evolution

The pathogen best studied using aDNA analysis so far is Y. pestis, the causative agent of plague. To date, 38 ancient genomes of this bacterium have been published20,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 (Fig. 4), and their analyses have yielded valuable information on past pandemic emergence as well as in-depth microbial evolution. Integration of such knowledge into human population frameworks has provided key insights into the association of human migrations and infectious disease transmission in the past31,34. This section describes the evolutionary history of Y. pestis with the aim of demonstrating aspects of its emergence and spread as revealed through aDNA research.

Not a human pathogen: plague ecology

Plague is a well-defined infectious disease caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Y. pestis, which belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae. It evolved from a close relative, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, which is an environmental enteric-disease-causing bacterium136. Although the two species are clearly distinguishable in terms of their virulence potential and transmission mechanisms, their nucleotide genomic identity reaches 97% among chromosomal protein-coding genes137. In addition, they share the virulence plasmid pCD1, which encodes a type III secretion system common to three known pathogenic Yersinia: Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica. The distinct transmission mechanism and pathogenicity of Y. pestis are conferred by the unique acquisition of two plasmids, pPCP1, which contributes to the invasive potential of the bacterium138, and pMT1, which is involved in flea colonization139,140, as well as by chromosomal gene pseudogenization or loss throughout its evolutionary history141.

Y. pestis is not human adapted. Its primary hosts are sylvatic rodents such as marmots, mice, great gerbils, voles and prairie dogs, among others, in which it is continuously or intermittently maintained in so-called reservoirs or foci142,143,144. Its global distribution includes numerous rodent species144,145 and encompasses regions in eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas (Fig. 4), where the bacterium persists in active foci, some of which have existed for centuries or even millennia31,33,34,37,130. Y. pestis transmission among hosts is facilitated by a flea vector (Fig. 5). The best yet characterized is the oriental rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, although others are also known to play important roles in Y. pestis transmission142,144,146. Notably, recent modelling inferences suggest important roles for ectoparasites such as body lice and human fleas in its propagation during human epidemics147. Landmark studies investigating the classical model of transmission have shown that Y. pestis has the unique ability to colonize and form a biofilm within the flea, which blocks a portion of its foregut, the proventriculus (Fig. 5). This phenotype is determined by the unique acquisition and activity of certain genomic loci in Y. pestis, namely, the Yersinia murine toxin (ymt) gene, which is present on the pMT1 plasmid140,141 and facilitates colonization of the arthropod midgut141. In addition, it is dependent on the pseudogenization of certain genes, namely, the biofilm downregulators rcsA, PDE2 (also known as rtn), PDE3 (also known as y3389)141 and the urease gene ureD148,149, which are, by contrast, active in Y. pseudotuberculosis. The biofilm prevents a blood meal from entering the flea’s digestive tract, leaving it starving; as a result, the insect intensifies its feeding behaviour and promotes bacterial transmission to uninfected hosts150,151,152. This continuous transmission cycle among fleas and rodents, also called the enzootic phase of maintenance (Fig. 5), is thought to drive the preservation of plague foci around the world and is dependent on environmental and climatic factors as well as on host population densities142,153,154,155. Disruption of this equilibrium for reasons that are not well understood can cause disease eruption among susceptible rodent species, leading to so-called plague epizootics142 (Fig. 5). During that time, marked reductions in the rodent populations force fleas to seek alternative hosts, which can lead to infections in humans and, as a result, trigger the initiation of epidemics or pandemics.

Published ancient specimens that have yielded whole Yersinia pestis genomes and genome-wide data are shown in triangles (n = 38), and their different colours indicate time period distinctions. A set of modern Y. pestis genomes (n = 336), from the following publications (released until 2018)92,130,169,170,171,172,173,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200, are shown as grey circles within their geographical country or region of isolation, and the size of each circle is proportional to the number of strains sequenced from each location (number indicated when more than one genome is shown). The areas highlighted in brown are regions that contain active plague foci as determined by contemporary or historical data. ybp, years before present. Adapted with permission from the ‘Global distribution of natural plague foci as of March 2016’ from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/plague/Plague-map-2016.pdf.

A simplified version of the Yersinia pestis enzootic cycle, during which the bacterium is maintained among wild rodent populations through a flea-dependent transmission mechanism. Under poorly understood circumstances, plague epizootics, which are best explained as animal epidemics, can occur among susceptible rodent populations. During those periods, humans and other mammals are at highest risk of becoming infected with Y. pestis. Plague can manifest in humans in the bubonic, pneumonic and septicaemic forms. Pneumonic plague is the only form that can result in airborne transmission between humans.

Plague manifestation in humans has three disease forms, namely, bubonic, pneumonic and septicaemic156. Bubonic plague is the most common form of the disease and can cause up to 60% mortality when left untreated157. Subsequent to the bite of an infected flea, bacteria travel to the closest lymph node, where excessive replication occurs, giving rise to large swellings, the so-called buboes. In addition, following primary bubonic plague, bacteria can disseminate into the bloodstream to cause septicaemia (secondary septicaemic plague) and to the lungs, causing secondary pneumonic disease. Both forms are highly lethal disease presentations and cause nearly 100% mortality when left untreated. Only the pneumonic form can result in direct human-to-human transmission.

Early evolution: plague in prehistory

The time of divergence between Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis has been difficult to determine given the wide temporal interval produced by recent molecular dating attempts based on aDNA data (13,000–79,000 years before present (ybp))33,34. Nevertheless, Y. pestis identification in human remains from Neolithic and Bronze Age Eurasia suggests that it caused human infections during these periods and originated more than 5,000 years ago31,33,34. These data have revealed important details about the early evolution of the bacterium. Genomic and phylogenetic analyses have shown that strains from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (LNBA) occupy a basal lineage in the Y. pestis phylogeny, and a recent study suggests the presence of even more basal variants in Neolithic Europe31 (Fig. 6). Such analyses have demonstrated that, during its early evolution, the bacterium had not yet acquired important virulence factors consistent with the complex transmission cycle common to historical and extant strains. One of these genes is ymt, whose absence has been associated with an inability for flea midgut colonization in Y. pestis141. In addition, these strains possess the active forms of the rcsA, PDE3, PDE2 and ureD genes, which suggests an impaired ability towards biofilm formation and blockage of the flea’s proventriculus141,149. Finally, they possess an active flagellin gene (flhD), which is present as a pseudogene in all other Y. pestis, as it is a potent inducer of the innate immune response of the host158. As a result, during its initial evolutionary stages, Y. pestis may have been unable to efficiently transmit via a flea vector. Flea-borne transmission of Y. pestis is a known prerequisite for bubonic plague development141; hence, it has been suggested that this disease phenotype was not present during prehistoric times33,159. In addition, these results have raised uncertainty regarding the possible vector and host mammalian species of the bacterium. The Bronze Age in Eurasia was a period of intense human migrations, which shaped the genomic landscape of modern-day Europe85,160. Remarkably, the Y. pestis LNBA lineage was shown to mirror human movements during that time34 and was found in regions that do not host wild reservoir populations today (Fig. 4). The wide geographical distribution of these strains, their supposed limited bubonic disease potential and their relationship with human migration routes might together be indicative of a different reservoir host species compared to wild rodents that have a central role in plague transmission in areas such as Central and East Asia, where the disease is endemic today.

A phylogenetic tree graphic depicting the evolutionary history of Yersinia pestis based on both ancient and modern genomes. Ancient strains that have been previously characterized by phylogenetic analysis are represented with coloured circles among the tree branches as follows: a Middle Neolithic genome is shown in yellow; Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (LNBA) genomes are shown in purple; a Late Bronze Age genome (RT5) encompassing signatures of flea adaptation is shown in blue; a pre-Justinian, 2nd century of the current era (ce), genome is shown in green; first-plague-pandemic genomes are shown in black; second plague pandemic, 14th-century genomes are shown in red; and post-Black Death (up until 18th century ce) genomes are shown in grey. Modern lineages are simplified and shown as branches of equal length in order to enhance the clarity of the graphic. The geographical distribution of modern strains is as follows (using universal country abbreviations): branch 1 (UGA, DRC, KEN, DZA, MDG, CHN, IND, IDN, MNM, USA and PER), branch 2 (RUS, AZE, KAZ, KGZ, UZB, TKM, CHN, IRN and NPL), branch 3 (CHN and MNG), branch 4 (RUS and MNG) and branch 0, including lineages 0.ANT3 (CHN and KGZ), 0.ANT5 (KGZ and KAZ), 0.ANT2 (CHN), 0.ANT1 (CHN), 0.PE5 (MNG), 0.PE4 (TJK, UZB, KGZ, RUS, CHN and MNG), 0.PE2 (GEO, ARM, AZE and RUS) and 0.PE7 (CHN). ybp, years before present.

Nevertheless, an alternative mode of flea transmission, termed the early phase transmission, which occurs during the initial phases of infection and was suggested to be biofilm-independent161, should also be considered as a possible way of Y. pestis propagation during its early evolution34. Although this transmission mechanism is currently not well understood, its comparative mode and efficiency in different rodent species have recently started to be assessed162. The oldest Y. pestis genomic evidence showing the full capacity for flea colonization similar to modern and historic strains was identified in two 3,800-year-old skeletons from the Samara region of modern-day Russia37. Although this strain was shown to occupy a phylogenetic position among modern Y. pestis lineages (Fig. 6), molecular dating analysis indicated that it originated ~4,000 years ago, suggesting that it overlapped temporally with the other Bronze Age strains that lacked the genetic prerequisites for arthropod transmission. Similar characteristics were previously identified in a low-coverage 3,000-year-old isolate from modern-day Armenia33, which suggests that multiple forms of the bacterium were circulating in Eurasia between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago that may have had different transmission cycles and produced different disease phenotypes. As the propagation mechanisms of those strains are still uncertain, and the exact timing of flea-adaptation in Y. pestis is unknown, additional metagenomic screening from human and animal remains may provide relevant information on disease reservoirs and hosts across Neolithic and Bronze Age Eurasia.

It is becoming increasingly apparent that, aside from plague, other infectious diseases, such as those caused by HBV43,44 and B19V45 (Table 1), were circulating during the same time periods. Further pathogen screening coupled with a temporal assessment of human immune-associated genomic variants84 may reveal key aspects of disease prevalence and susceptibility during this pivotal period of human history.

Molecular insights from three historical plague pandemics

After the Bronze Age, bubonic plague has been associated with three historically recorded pandemics. The earliest accounts of the so-called first plague pandemic, which began with the Plague of Justinian (541 ce), suggest that it erupted in northern Africa in the mid-6th century ce163,164 and subsequently spread through Europe and the vicinity until ~750 ce. The second historically recorded plague pandemic began with the infamous Black Death (1346–1353 ce)96 and continued with outbreaks in Europe until the 18th century ce. The most recent third plague pandemic began in the mid-19th century in the Yunnan province of China, and it was during that time that Alexandre E. J. Yersin first described the bacterium in Hong Kong, in 1894 (Fig. 1). The third pandemic spread worldwide via marine routes and has persisted until today in active foci in Africa, Asia and the Americas. Although the majority of modern plague cases derive from strains disseminated in this global dispersal, the pandemic is considered to have largely subsided since the 1950s165.

The association of Y. pestis with the two earlier pandemics has, until recent years, been contentious. On the basis of their serological characterization, modern strains were traditionally grouped into three distinct biovars, namely, ‘antiqua’, ‘medievalis’ and ‘orientalis’, according to their ability to ferment glycerol and reduce nitrate165,166. In addition, historical accounts of the disease seemed to correlate with the supposed distinct geographical distributions of these biovars166, and their phylogenetic relationships, as inferred from MLST data, reinforced the hypothesis that each was responsible for a single pandemic136. By contrast, later studies identified additional, atypical biovars167, and more robust phylogenetic analysis suggested that phylogeography does not correlate clearly with the phenotypic distinctions described between these bacterial populations92,130,168.

Recent genomic analyses have revealed high genetic diversity of the bacterium in East Asia, which invariably led to the assumption that Y. pestis emerged there130. However, a strong research focus on the diversity of the bacterium in these endemic regions, mainly China, has contributed to a profound sampling bias in the available modern data (Fig. 4). More recent investigations have revealed previously uncharacterized genetic diversity in the Caucasus region and in the central Asian steppe that ought to be further explored169,170,171,172 (Fig. 4). Currently, the evolutionary tree of the bacterium is characterized by five main phylogenetic branches (Fig. 6). The most ancestral, branch 0, includes strains distributed across China, Mongolia and the areas encompassing the former Soviet Union. The more phylogenetically derived branches 1–4 were formed through a rapid population expansion event and are today found in Asia, Africa and the Americas130. Their wide distribution mainly reflects the geographical breadth of branch 1, which is associated with the third plague pandemic that spread worldwide during the 19th and 20th centuries92 and is still responsible for more confined epidemics such as those reported in Madagascar173.

The analysis of aDNA from historical epidemic contexts has generated important information regarding the evolutionary history of plague. The recovery of Y. pestis DNA via PCR from remnants of human dental pulp suggested the involvement of the bacterium in both the first and second pandemics; however, these results were difficult to authenticate8,174,175. Subsequent PCR-based SNP typing of ancient specimens offered some phylogenetic resolution and revealed an expected ancestral placement of medieval strains in the Y. pestis phylogeny62,63,64. More recently, full characterization and authentication of the bacterium were achieved using plasmid and whole-genome enrichment coupled with NGS17,20,35,36.

Historical accounts of the first plague pandemic (6th to 8th centuries ce) suggest that the disease expanded mainly across the Mediterranean basin; however, its exact breadth and impact have been difficult to assess given the limited availability of historical and archaeological data, with the latter being currently under revision176. Two recent studies have reconstructed 6th-century Y. pestis genomes from southern Germany35,36 (Fig. 4), a region that lacked historical documentation of the pandemic. Phylogenetic analysis showed that both genomes belong to a lineage that is today extinct and is closely related to strains from modern-day China35,36, which suggests the possibility of an East Asian origin of the first pandemic. This hypothesis was recently reinforced by the publication of a 2nd-century to 3rd-century Y. pestis genome from the Tian Shan mountains of modern-day Kyrgyzstan39, which shares a common ancestor with the Justinianic-plague lineage (Figs 4,6). However, given the >300-year age difference between these strains35,36,39, as well as the aforementioned East Asian sampling bias of modern Y. pestis data130, the geographical origin of the pandemic remains hypothetical. Retrieval of additional Y. pestis strain diversity from that time period, particularly from areas known to have played an important role in the entry of this bacterium into Europe, that is, the eastern Mediterranean region, may hold clues about its putative source.

The beginning of the second plague pandemic, 600 years later, was marked by the notorious Black Death of Europe (1346–1353 ce), estimated to have caused an up to 60% reduction of the continental population in only 5 years96. Historical records suggest that the first outbreaks occurred in the Lower Volga region of Russia, and the disease then spread into southern Europe through the Crimean peninsula96. Initial analysis of Y. pestis via PCR from victims of the Black Death revealed a distinct phylogenetic positioning of two mid-to-late-14th-century strains and led to the proposal that the disease entered the continent through independent pulses64. By contrast, whole-genome analysis of ancient strains from western, northern and southern Europe demonstrated a lack of Y. pestis diversity during the Black Death, which suggests its fast spread through the continent and favours a single-wave entry model of the bacterium into Europe20,30,38, although the possible presence of additional strain diversity during that time has recently been explored30. Intriguingly, the phylogenetic positioning of the Black Death Y. pestis genomes places them on branch 1, only two nucleotide substitutions away from the ‘star-like’ diversification of branches 1–4 (Fig. 6), which gave rise to most of the strain diversity identified around the world today38,130.

After the Black Death, plague epidemics continued to affect Europe until the 18th century177,178. Inferred climatic data from tree ring records in central Asia and Europe have recently suggested that such epidemics were likely caused by multiple introductions of the bacterium into Europe as a result of climate-driven disruptions of pre-existing Asian reservoirs179. By contrast, ancient genetic and genomic evidence supports the persistence of the disease in Europe for 400 years after the Black Death32,38,62. Analysis of Y. pestis strains spanning from the late 14th to the 18th century ce has revealed the formation of at least two European lineages that were responsible for the ensuing medieval epidemics (Fig. 6). Both lineages derive from the Black Death Y. pestis strain identified in 14th-century western, northern and southern Europe30,32,38, suggesting that they likely arose locally. The first lineage survives today and gave rise to modern branch 1 strains30,38 (which are associated with the third plague pandemic), suggesting the European Black Death as a source for modern-day epidemics38. The second lineage has not been identified among present-day diversity and currently encompasses strains from 16th-century Germany38 and 18th-century France (Great Plague of Marseille, 1720–1722 ce) (Fig. 6). These phylogenetic patterns are consistent with a continuous persistence of the bacterium in Europe during the second plague pandemic. In addition, they are supported by analyses of historical records that suggest the existence of plague reservoirs in the continent until the 18th century ce180.

Y. pestis is absent from most of Europe today; specifically, no active foci exist west of the Black Sea. Plague is thought to have disappeared from most of Europe at the end of the second pandemic (18th century ce). This finding is striking given the thousands of outbreaks that were recorded in the continent until that time177,178. The reasons for its disappearance are unknown, although numerous hypotheses have been put forward181, including a change in domestic rodent populations in Europe, namely, the replacement of the black rat, Rattus rattus, by the brown rat, Rattus norvegicus181; an acquired plague immunity among humans and/or rodents181 (although this hypothesis requires an update to accommodate the recent identification of Y. pestis in Europe 5,000 years ago31,33,34 and the involvement of the bacterium in the first plague pandemic35,36); the increased living standards such as the better nutrition and hygienic conditions at the beginning of the Early Modern Era, which may have contributed to improved overall health conditions in Europe and likely decreased the number of rats and ectoparasites in human environments181,182; and the potential disruption of the European wild rodent ecological niche owing to habitat loss and industrialization starting in 1700 ce180. Given the contribution that molecular data can offer in these discussions, future research on ancient sources of Y. pestis DNA will be instrumental in further revealing the history of one of humankind’s most devastating pathogens.

Conclusions

The analysis of ancient pathogen genomes has afforded promising views into past infectious disease history. For Y. pestis, aDNA exploration of its evolutionary past has revealed how a predominantly environmental bacterium and opportunistic gastroenteric pathogen developed into an extremely virulent form by acquisition of only a few virulence factors. We eagerly await revelations on a similar scale for other important pathogens that are expected to arise from deep temporal sampling and genomic reconstruction, as made possible through the recent advancements discussed here.

Integration of ancient pathogen genomes into disease modelling and human population genetic frameworks, as well as their analysis alongside the information offered by the archaeological, historical and palaeopathological records, will help build a more interdisciplinary and complete picture of host–pathogen interactions and human evolutionary history over time.

References

Armelagos, G. J., Goodman, A. H. & Jacobs, K. H. The origins of agriculture: population growth during a period of declining health. Popul. Environ. 13, 9–22 (1991).

Barrett, R., Kuzawa, C. W., McDade, T. & Armelagos, G. J. Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases: the third epidemiologic transition. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 27, 247–271 (1998).

Ortner, D. J. Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains 2nd edn (Academic Press, 2003).

Buikstra, J. E. & Roberts, C. The Global History of Paleopathology: Pioneers and Prospects (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

Arriaza, B. T., Salo, W., Aufderheide, A. C. & Holcomb, T. A. Pre-Columbian tuberculosis in Northern Chile: molecular and skeletal evidence. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 98, 37–45 (1995).

Salo, W. L., Aufderheide, A. C., Buikstra, J. & Holcomb, T. A. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in a pre-Columbian Peruvian mummy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2091–2094 (1994).

Zink, A., Haas, C. J., Reischl, U., Szeimies, U. & Nerlich, A. G. Molecular analysis of skeletal tuberculosis in an ancient Egyptian population. J. Med. Microbiol. 50, 355–366 (2001).

Drancourt, M., Aboudharam, G., Signoli, M., Dutour, O. & Raoult, D. Detection of 400-year-old Yersinia pestis DNA in human dental pulp: an approach to the diagnosis of ancient septicemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12637–12640 (1998).

Spigelman, M. & Lemma, E. The use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis in ancient skeletons. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 3, 137–143 (1993).

Pääbo, S. Ancient DNA: extraction, characterization, molecular cloning, and enzymatic amplification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1939–1943 (1989).

Sawyer, S., Krause, J., Guschanski, K., Savolainen, V. & Paabo, S. Temporal patterns of nucleotide misincorporations and DNA fragmentation in ancient DNA. PLOS ONE 7, e34131 (2012).

Briggs, A. W. et al. Patterns of damage in genomic DNA sequences from a Neandertal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 14616–14621 (2007). The study provides a quantitative description of aDNA-associated patterns of nucleotide misincorporation and fragmentation that are currently used as primary authentication criteria.

Cooper, A. & Poinar, H. N. Ancient DNA: do it right or not at all. Science 289, 1139–1139 (2000).

Gilbert, M. T. P. et al. Absence of Yersinia pestis-specific DNA in human teeth from five European excavations of putative plague victims. Microbiology 150, 341–354 (2004).

Shapiro, B., Rambaut, A. & Gilbert, M. T. P. No proof that typhoid caused the Plague of Athens (a reply to Papagrigorakis et al.). Int. J. Infect. Dis. 10, 334–335 (2006).

Margulies, M. et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437, 376 (2005).

Schuenemann, V. J. et al. Targeted enrichment of ancient pathogens yielding the pPCP1 plasmid of Yersinia pestis from victims of the Black Death. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, E746–E752 (2011).

Green, R. E. et al. The Neandertal genome and ancient DNA authenticity. EMBO J. 28, 2494–2502 (2009).

Key, F. M., Posth, C., Krause, J., Herbig, A. & Bos, K. I. Mining metagenomic data sets for ancient DNA: recommended protocols for authentication. Trends Genet. 33, 508–520 (2017).

Bos, K. I. et al. A draft genome of Yersinia pestis from victims of the Black Death. Nature 478, 506–510 (2011). The study describes the first whole-genome sequence of an ancient bacterial pathogen through the use of high-throughput sequencing.

Pääbo, S. et al. Genetic analyses from ancient DNA. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38, 645–679 (2004).

Dabney, J., Meyer, M. & Pääbo, S. Ancient DNA damage. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a012567 (2013).

Pinhasi, R. et al. Optimal ancient DNA yields from the inner ear part of the human petrous bone. PLOS ONE 10, e0129102 (2015).

Hansen, H. B. et al. Comparing ancient DNA preservation in petrous bone and tooth cementum. PLOS ONE 12, e0170940 (2017).

Margaryan, A. et al. Ancient pathogen DNA in human teeth and petrous bones. Ecol. Evol. 8, 3534–3542 (2018).

Bos, K. I. et al. Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis. Nature 514, 494–497 (2014).

Schuenemann, V. J. et al. Ancient genomes reveal a high diversity of Mycobacterium leprae in medieval Europe. PLOS Pathog. 14, e1006997 (2018).

Schuenemann, V. J. et al. Genome-wide comparison of medieval and modern Mycobacterium leprae. Science 341, 179–183 (2013). The study presents the first de novo assembled ancient pathogen genome and an analysis of M. leprae in medieval Europe.

Schuenemann, V. J. et al. Historic Treponema pallidum genomes from Colonial Mexico retrieved from archaeological remains. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12, e0006447 (2018).

Namouchi, A. et al. Integrative approach using Yersinia pestis genomes to revisit the historical landscape of plague during the Medieval Period. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E11790–E11797 (2018).

Rascovan, N. et al. Emergence and spread of basal lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic Decline. Cell 176, 295–305 (2018).

Bos, K. I. et al. Eighteenth century Yersinia pestis genomes reveal the long-term persistence of an historical plague focus. eLife 5, e12994 (2016).

Rasmussen, S. et al. Early divergent strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 years ago. Cell 163, 571–582 (2015). The study describes Y. pestis genomes from Bronze Age human remains and provides a chronological timing of virulence determinant acquisition during the early evolution of the bacterium.

Andrades Valtueña, A. A. et al. The Stone Age plague and its persistence in Eurasia. Curr. Biol. 27, 3683–3691 (2017).

Feldman, M. et al. A high-coverage Yersinia pestis genome from a sixth-century justinianic plague victim. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 2911–2923 (2016).

Wagner, D. M. et al. Yersinia pestis and the Plague of Justinian 541–543 AD: a genomic analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 319–326 (2014). The study reports the first genome-wide analysis of Y. pestis from victims of the Plague of Justinian, directly implicating the bacterium in the first plague pandemic.

Spyrou, M. A. et al. Analysis of 3800-year-old Yersinia pestis genomes suggests Bronze Age origin for bubonic plague. Nat. Commun. 9, 2234 (2018). This paper presents the oldest genomic evidence of flea adaptation in Y. pestis.

Spyrou, M. A. et al. Historical Y. pestis genomes reveal the European Black Death as the source of ancient and modern plague pandemics. Cell Host Microbe 19, 874–881 (2016).

de Barros Damgaard, P. et al. 137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes. Nature 557, 369 (2018).

Guellil, M. et al. Genomic blueprint of a relapsing fever pathogen in 15th century Scandinavia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10422–10427 (2018).

Vågene, A. J. et al. Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major sixteenth-century epidemic in Mexico. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 520–528 (2018). This paper presents the metagenomic tool MALT and is the first case study to demonstrate metagenomic detection of ancient pathogens in the absence of prior knowledge on the causative agent of an epidemic.

Marciniak, S. et al. Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 1st−2nd century CE southern Italy. Curr. Biol. 26, R1220–R1222 (2016).

Mühlemann, B. et al. Ancient hepatitis B viruses from the Bronze Age to the Medieval period. Nature 557, 418–423 (2018).

Krause-Kyora, B. et al. Neolithic and Medieval virus genomes reveal complex evolution of hepatitis B. eLife 7, e36666 (2018). The studies by Mühlemann (Nature, 2018) and Krause-Kyora (eLife, 2018) present a time transect of HBV genomes, spanning from the Neolithic period to the medieval period, and provide an overview of the HBV population history across millennia.

Mühlemann, B. et al. Ancient human parvovirus B19 in Eurasia reveals its long-term association with humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 7557–7562 (2018).

Warinner, C. et al. Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nat. Genet. 46, 336 (2014). This study provides an analysis of the composition of human dental calculus from ancient individuals, showing the presence of oral microbiome bacterial DNA, periodontal pathogen DNA and proteins associated with host immunity.

Kay, G. L. et al. Recovery of a medieval Brucella melitensis genome using shotgun metagenomics. mBio 5, e01337–14 (2014).

Devault, A. M. et al. A molecular portrait of maternal sepsis from Byzantine Troy. eLife 6, e20983 (2017).

Maixner, F. et al. The 5300-year-old Helicobacter pylori genome of the Iceman. Science 351, 162–165 (2016). The study provides insights into the genomic history of H. pylori over several millennia through a population genomic analysis of a Copper Age strain against a worldwide data set.

Duggan, A. T. et al. 17th century variola virus reveals the recent history of smallpox. Curr. Biol. 26, 3407–3412 (2016).

Biagini, P. et al. Variola virus in a 300-year-old Siberian mummy. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2057–2059 (2012).

Kay, G. L. et al. Eighteenth-century genomes show that mixed infections were common at time of peak tuberculosis in Europe. Nat. Commun. 6, 6717 (2015).

Ross, Z. P. et al. The paradox of HBV evolution as revealed from a 16th century mummy. PLOS Pathog. 14, e1006750 (2018).

Kahila Bar-Gal, G. et al. Tracing hepatitis B virus to the 16th century in a Korean mummy. Hepatology 56, 1671–1680 (2012).

Devault, A. M. et al. Second-pandemic strain of Vibrio cholerae from the Philadelphia cholera outbreak of 1849. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 334–340 (2014).

Gelabert, P. et al. Mitochondrial DNA from the eradicated European Plasmodium vivax and P. falciparum from 70-year-old slides from the Ebro Delta in Spain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11495–11500 (2016).

Worobey, M. et al. 1970s and ‘patient 0’HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America. Nature 539, 98 (2016).

Taubenberger, J. K. et al. Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes. Nature 437, 889 (2005).

Yoshida, K. et al. The rise and fall of the Phytophthora infestans lineage that triggered the Irish potato famine. eLife 2, e00731 (2013).

Martin, M. D. et al. Reconstructing genome evolution in historic samples of the Irish potato famine pathogen. Nat. Commun. 4, 2172 (2013).

Harkins, K. M. et al. Screening ancient tuberculosis with qPCR: challenges and opportunities. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20130622 (2015).

Seifert, L. et al. Genotyping Yersinia pestis in historical plague: evidence for long-term persistence of Y. pestis in Europe from the 14th to the 17th century. PLOS ONE 11, e0145194 (2016).

Harbeck, M. et al. Yersinia pestis DNA from skeletal remains from the 6th century AD reveals insights into Justinianic Plague. PLOS Pathog. 9, e1003349 (2013).

Haensch, S. et al. Distinct clones of Yersinia pestis caused the black death. PLOS Pathog. 6, e1001134 (2010).

Bos, K. I. et al. Parallel detection of ancient pathogens via array-based DNA capture. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20130375 (2015).

Devault, A. M. et al. Ancient pathogen DNA in archaeological samples detected with a microbial detection array. Sci. Rep. 4, 4245 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595 (2010).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

O’Leary, N. A. et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D733–D745 (2015).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic microbial community profiling using unique clade-specific marker genes. Nat. Methods 9, 811 (2012).

Louvel, G., Der Sarkissian, C., Hanghøj, K. & Orlando, L. metaBIT, an integrative and automated metagenomic pipeline for analysing microbial profiles from high-throughput sequencing shotgun data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 16, 1415–1427 (2016).

Wood, D. E. & Salzberg, S. L. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46 (2014).

Warinner, C. et al. A robust framework for microbial archaeology. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 18, 321–356 (2017).

Müller, R., Roberts, C. A. & Brown, T. A. Complications in the study of ancient tuberculosis: Presence of environmental bacteria in human archaeological remains. J. Archaeol. Sci. 68, 5–11 (2016).

Hofreiter, M., Jaenicke, V., Serre, D., Haeseler, A. v. & Pääbo, S. DNA sequences from multiple amplifications reveal artifacts induced by cytosine deamination in ancient DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4793–4799 (2001).

Jonsson, H., Ginolhac, A., Schubert, M., Johnson, P. L. & Orlando, L. mapDamage2.0: fast approximate Bayesian estimates of ancient DNA damage parameters. Bioinformatics 29, 1682–1684 (2013).

Briggs, A. W. et al. Removal of deaminated cytosines and detection of in vivo methylation in ancient DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e87 (2010).

Rohland, N., Harney, E., Mallick, S., Nordenfelt, S. & Reich, D. Partial uracil-DNA-glycosylase treatment for screening of ancient DNA. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20130624 (2015).

Hodges, E. et al. Hybrid selection of discrete genomic intervals on custom-designed microarrays for massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 4, 960–974 (2009).

Burbano, H. A. et al. Targeted investigation of the Neandertal genome by array-based sequence capture. Science 328, 723–725 (2010).

Fu, Q. et al. DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 2223–2227 (2013).

Ávila-Arcos, M. C. et al. Application and comparison of large-scale solution-based DNA capture-enrichment methods on ancient DNA. Sci. Rep. 1, 74 (2011).

Cruz-Dávalos, D. I. et al. Experimental conditions improving in-solution target enrichment for ancient DNA. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17, 508–522 (2017).

Mathieson, I. et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 528, 499–503 (2015).

Haak, W. et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207–211 (2015). This study delineates large-scale population migrations into Europe during the Bronze Age by analysis of human genome-wide data of individuals living between 8,000 and 3,000 y bp.

Lazaridis, I. et al. Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East. Nature 536, 419–424 (2016).

Lazaridis, I. et al. Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Nature 548, 214–218 (2017).

Posth, C. et al. Language continuity despite population replacement in Remote Oceania. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 731 (2018).

Rasmussen, M. et al. Ancient human genome sequence of an extinct Palaeo-Eskimo. Nature 463, 757–762 (2010).

Prüfer, K. et al. The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature 505, 43–49 (2014).

Meyer, M. et al. A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan individual. Science 338, 222–226 (2012).

Morelli, G. et al. Yersinia pestis genome sequencing identifies patterns of global phylogenetic diversity. Nat. Genet. 42, 1140–1143 (2010).

Comas, I. et al. Out-of-Africa migration and Neolithic coexpansion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with modern humans. Nat. Genet. 45, 1176 (2013). The study shows a possible co-expansion of M. tuberculosis among human populations during out-of-Africa migrations.

Roberts, C. A. & Buikstra, J. E. The Bioarchaeology of Tuberculosis: a Global Perspective on a Re-Emerging Disease (Univ. Press of Florida, 2003).

Cohn, S. K. Jr. The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe (Arnold, 2002).

Benedictow, O. J. The Black Death, 1346-1353: The Complete History (Boydell & Brewer, 2004).

Ortner, D. J. in Advances in Human Palaeopathology (eds Pinhasi, R. & Mays, S.) 189–214 (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

Cunha, C. B. & Cunha, B. A. in Paleomicrobiology: Past Human Infections (eds Raoult, D. & Drancourt, M.) 1–20 (Springer, 2008).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 (2003).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2014).

Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003).

Huson, D. H. & Bryant, D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 254–267 (2005).

Krause-Kyora, B. et al. Ancient DNA study reveals HLA susceptibility locus for leprosy in medieval Europeans. Nat. Commun. 9, 1569 (2018).

Robbins, G. et al. Ancient skeletal evidence for leprosy in India (2000 BC). PLOS ONE 4, e5669 (2009).

Köhler, K. et al. Possible cases of leprosy from the Late Copper Age (3780–3650 cal BC) in Hungary. PLOS ONE 12, e0185966 (2017).

Wong, S. H. et al. Leprosy and the adaptation of human toll-like receptor 1. PLOS Pathog. 6, e1000979 (2010).

Zhou, Z. et al. Pan-genome analysis of ancient and modern Salmonella enterica demonstrates genomic stability of the invasive para C lineage for millennia. Curr. Biol. 28, 2420–2428 (2018). The study describes a 12th century Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi C genome and its analysis alongside a comprehensive data set of thousands of S. enterica strains.

Didelot, X. & Wilson, D. J. ClonalFrameML: efficient inference of recombination in whole bacterial genomes. PLOS Comp. Biol. 11, e1004041 (2015).

Martin, D. P., Murrell, B., Golden, M., Khoosal, A. & Muhire, B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 1, vev003 (2015).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000).

Lawson, D. J., Hellenthal, G., Myers, S. & Falush, D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLOS Genet. 8, e1002453 (2012).

Schmidt, H. A., Strimmer, K., Vingron, M. & von Haeseler, A. TREE-PUZZLE: maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics 18, 502–504 (2002).

Monot, M. et al. On the origin of leprosy. Science 308, 1040–1042 (2005).