Abstract

Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a promising therapy for chronic diseases associated with gut microbiota alterations. FMT cures 90% of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections. However, in complex diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome and metabolic syndrome, its efficacy remains variable. It is accepted that donor selection and sample administration are key determinants of FMT success, yet little is known about the recipient factors that affect it. In this Perspective, we discuss the effects of recipient parameters, such as genetics, immunity, microbiota and lifestyle, on donor microbiota engraftment and clinical efficacy. Emerging evidence supports the possibility that controlling inflammation in the recipient intestine might facilitate engraftment by reducing host immune system pressure on the newly transferred microbiota. Deciphering FMT engraftment rules and developing novel therapeutic strategies are priorities to alleviate the burden of chronic diseases associated with an altered gut microbiota such as inflammatory bowel disease.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Eckburg, P. B. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308, 1635–1638 (2005).

D’Haens, G. R. & Jobin, C. Fecal microbial transplantation for diseases beyond recurrent clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 157, 624–636 (2019).

Durack, J. & Lynch, S. V. The gut microbiome: relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. J. Exp. Med. 216, 20–40 (2019).

Vujkovic-Cvijin, I. et al. Host variables confound gut microbiota studies of human disease. Nature 587, 448–454 (2020).

Lloyd-Price, J. et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 569, 655–662 (2019).

Galipeau, H. J. et al. Novel fecal biomarkers that precede clinical diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.004 (2020).

Britton, G. J. et al. Microbiotas from humans with inflammatory bowel disease alter the balance of gut Th17 and RORγt+ regulatory T cells and exacerbate colitis in mice. Immunity 50, 212–224 (2019).

Le Roy, T. et al. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut 62, 1787–1794 (2013).

De Palma, G. et al. Transplantation of fecal microbiota from patients with irritable bowel syndrome alters gut function and behavior in recipient mice. Sci. Transl Med. 9, eaaf6397 (2017).

van Nood, E. et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 407–415 (2013).

Kelly, C. R. et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent clostridium difficile infection: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 165, 609 (2016).

Moayyedi, P. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 149, 102–109 (2015).

Rossen, N. G. et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 149, 110–118 (2015).

Paramsothy, S. et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 389, 1218–1228 (2017).

Costello, S. P. et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321, 156 (2019).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 146, 85–95 (2014).

Feagan, B. G. et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 699–710 (2013).

Colman, R. J. & Rubin, D. T. Fecal microbiota transplantation as therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crohns Colitis 8, 1569–1581 (2014).

Cui, B. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation through mid-gut for refractory Crohn’s disease: safety, feasibility, and efficacy trial results: fecal microbiota transplantation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 30, 51–58 (2015).

Suskind, D. L. et al. Fecal microbial transplant effect on clinical outcomes and fecal microbiome in active Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21, 556–563 (2015).

Vaughn, B. P. et al. Increased intestinal microbial diversity following fecal microbiota transplant for active Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 2182–2190 (2016).

He, Z. et al. Multiple fresh fecal microbiota transplants induces and maintains clinical remission in Crohn’s disease complicated with inflammatory mass. Sci. Rep. 7, 4753 (2017).

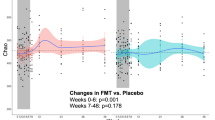

Sokol, H. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation to maintain remission in Crohn’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled study. Microbiome 8, 12 (2020).

Johnsen, P. H. et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation versus placebo for moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-centre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3, 17–24 (2018).

El-Salhy, M., Hatlebakk, J. G., Gilja, O. H., Bråthen Kristoffersen, A. & Hausken, T. Efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gut 69, 859–867 (2020).

Halkjær, S. I. et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation alters gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gut 67, 2107–2115 (2018).

Holster, S. et al. The effect of allogenic versus autologous fecal microbiota transfer on symptoms, visceral perception and fecal and mucosal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Clin. Transl Gastroenterol. 10, e00034 (2019).

Aroniadis, O. C. et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 675–685 (2019).

Kakihana, K. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease of the gut. Blood 128, 2083–2088 (2016).

Spindelboeck, W. et al. Repeated fecal microbiota transplantations attenuate diarrhea and lead to sustained changes in the fecal microbiota in acute, refractory gastrointestinal graft- versus -host-disease. Haematologica 102, e210–e213 (2017).

Qi, X. et al. Treating steroid refractory intestinal acute graft-vs.-host disease with fecal microbiota transplantation: a pilot study. Front. Immunol. 9, 2195 (2018).

Bajaj, J. S. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant from a rational stool donor improves hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. Hepatology 66, 1727–1738 (2017).

Bajaj, J. S. et al. Long-term outcomes of fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 156, 1921–1923 (2019).

Bajaj, J. S. et al. Microbial functional change is linked with clinical outcomes after capsular fecal transplant in cirrhosis. JCI Insight 4, e133410 (2019).

Bajaj, J. S. et al. A randomized clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplant for alcohol use disorder. Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31496 (2020).

Vrieze, A. et al. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology 143, 913–916 (2012).

Kootte, R. S. et al. Improvement of insulin sensitivity after lean donor feces in metabolic syndrome is driven by baseline intestinal microbiota composition. Cell Metab. 26, 611–619 (2017).

Kang, D.-W. et al. Microbiota transfer therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome 5, 10 (2017).

Kang, D.-W. et al. Long-term benefit of microbiota transfer therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 9, 5821 (2019).

Goodrich, J. K. et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell 159, 789–799 (2014).

Couturier-Maillard, A. et al. NOD2-mediated dysbiosis predisposes mice to transmissible colitis and colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 700–711 (2013).

Petnicki-Ocwieja, T. et al. Nod2 is required for the regulation of commensal microbiota in the intestine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15813–15818 (2009).

Hu, B. et al. Microbiota-induced activation of epithelial IL-6 signaling links inflammasome-driven inflammation with transmissible cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9862–9867 (2013).

Lamas, B. et al. CARD9 impacts colitis by altering gut microbiota metabolism of tryptophan into aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands. Nat. Med. 22, 598–605 (2016).

Khan, A. A. et al. Polymorphic immune mechanisms regulate commensal repertoire. Cell Rep. 29, 541–550 (2019).

Wen, L. et al. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of type 1 diabetes. Nature 455, 1109–1113 (2008).

Vijay-Kumar, M. et al. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking toll-like receptor 5. Science 328, 228–231 (2010).

Kawamoto, S. et al. Foxp3+ T cells regulate immunoglobulin a selection and facilitate diversification of bacterial species responsible for immune homeostasis. Immunity 41, 152–165 (2014).

Zhang, H., Sparks, J. B., Karyala, S. V., Settlage, R. & Luo, X. M. Host adaptive immunity alters gut microbiota. ISME J. 9, 770–781 (2015).

Dimitriu, P. A. et al. Temporal stability of the mouse gut microbiota in relation to innate and adaptive immunity: mouse gut microbiota dynamics. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5, 200–210 (2013).

Sokol, H. et al. Card9 mediates intestinal epithelial cell restitution, T-helper 17 responses, and control of bacterial infection in mice. Gastroenterology 145, 591–601 (2013).

Richard, M. L. & Sokol, H. The gut mycobiota: insights into analysis, environmental interactions and role in gastrointestinal diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 331–345 (2019).

Sovran, B. et al. Enterobacteriaceae are essential for the modulation of colitis severity by fungi. Microbiome 6, 152 (2018).

van Tilburg Bernardes, E. et al. Intestinal fungi are causally implicated in microbiome assembly and immune development in mice. Nat. Commun. 11, 2577 (2020).

Turpin, W. et al. Association of host genome with intestinal microbial composition in a large healthy cohort. Nat. Genet. 48, 1413–1417 (2016).

Bonder, M. J. et al. The effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome. Nat. Genet. 48, 1407–1412 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variation in vitamin D receptor and other host factors influencing the gut microbiota. Nat. Genet. 48, 1396–1406 (2016).

Benson, A. K. The gut microbiome-an emerging complex trait. Nat. Genet. 48, 1301–1302 (2016).

Hansen, J. J. Immune responses to intestinal microbes in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 15, 61 (2015).

Gevers, D. et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe 15, 382–392 (2014).

Morgan, X. C. et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol. 13, R79 (2012).

Chu, H. et al. Gene-microbiota interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Science 352, 1116–1120 (2016).

Sadaghian Sadabad, M. et al. The ATG16L1–T300A allele impairs clearance of pathosymbionts in the inflamed ileal mucosa of Crohn’s disease patients. Gut 64, 1546–1552 (2015).

Frank, D. N. et al. Disease phenotype and genotype are associated with shifts in intestinal-associated microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 17, 179–184 (2011).

Aschard, H. et al. Genetic effects on the commensal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease patients. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008018 (2019).

Sokol, H. et al. Intestinal dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143, 775–778 (2019).

Raffatellu, M. et al. Lipocalin-2 resistance confers an advantage to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium for growth and survival in the inflamed intestine. Cell Host Microbe 5, 476–486 (2009).

Liu, J. Z. et al. Zinc sequestration by the neutrophil protein calprotectin enhances Salmonella growth in the inflamed gut. Cell Host Microbe 11, 227–239 (2012).

Deriu, E. et al. Probiotic bacteria reduce Salmonella typhimurium intestinal colonization by competing for iron. Cell Host Microbe 14, 26–37 (2013).

Winter, S. E. et al. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science 339, 708–711 (2013).

Winter, S. E. & Bäumler, A. J. Dysbiosis in the inflamed intestine: chance favors the prepared microbe. Gut Microbes 5, 71–73 (2014).

Faber, F. & Bäumler, A. J. The impact of intestinal inflammation on the nutritional environment of the gut microbiota. Immunol. Lett. 162, 48–53 (2014).

Zechner, E. L. Inflammatory disease caused by intestinal pathobionts. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 35, 64–69 (2017).

Bunker, J. J. & Bendelac, A. IgA responses to microbiota. Immunity 49, 211–224 (2018).

van der Waaij, L. A. et al. Immunoglobulin coating of faecal bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 669–674 (2004).

Palm, N. W. et al. Immunoglobulin A coating identifies colitogenic bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 158, 1000–1010 (2014).

Viladomiu, M. et al. IgA-coated E. coli enriched in Crohn’s disease spondyloarthritis promote T H 17-dependent inflammation. Sci. Transl Med. 9, eaaf9655 (2017).

Aghamohammadi, A. et al. IgA deficiency: correlation between clinical and immunological phenotypes. J. Clin. Immunol. 29, 130–136 (2009).

Ludvigsson, J. F., Neovius, M. & Hammarström, L. Association between IgA deficiency & other autoimmune conditions: a population-based matched cohort study. J. Clin. Immunol. 34, 444–451 (2014).

Catanzaro, J. R. et al. IgA-deficient humans exhibit gut microbiota dysbiosis despite secretion of compensatory IgM. Sci. Rep. 9, 13574 (2019).

Mirpuri, J. et al. Proteobacteria-specific IgA regulates maturation of the intestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 5, 28–39 (2014).

Suzuki, K. et al. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1981–1986 (2004).

Harriman, G. R. et al. Targeted deletion of the IgA constant region in mice leads to IgA deficiency with alterations in expression of other Ig isotypes. J. Immunol. 162, 2521–2529 (1999).

Macpherson, A. J. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science 288, 2222–2226 (2000).

Kubinak, J. L. et al. MyD88 signaling in T cells directs IgA-mediated control of the microbiota to promote health. Cell Host Microbe 17, 153–163 (2015).

Kubinak, J. L. et al. MHC variation sculpts individualized microbial communities that control susceptibility to enteric infection. Nat. Commun. 6, 8642 (2015).

Nakajima, A. et al. IgA regulates the composition and metabolic function of gut microbiota by promoting symbiosis between bacteria. J. Exp. Med. 215, 2019–2034 (2018).

Zuo, T. et al. Gut fungal dysbiosis correlates with reduced efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Commun. 9, 3663 (2018).

Vermeire, S. et al. Donor species richness determines faecal microbiota transplantation success in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis 10, 387–394 (2016).

Paramsothy, S. et al. Specific bacteria and metabolites associated with response to fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 156, 1440–1454 (2019).

Lavelle, A. & Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 223–237 (2020).

McCarville, J. L., Chen, G. Y., Cuevas, V. D., Troha, K. & Ayres, J. S. Microbiota metabolites in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 38, 147–170 (2020).

Weingarden, A. R. et al. Microbiota transplantation restores normal fecal bile acid composition in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 306, G310–G319 (2014).

Buffie, C. G. et al. Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature 517, 205–208 (2015).

Staley, C., Kelly, C. R., Brandt, L. J., Khoruts, A. & Sadowsky, M. J. Complete microbiota engraftment is not essential for recovery from recurrent clostridium difficile infection following fecal microbiota transplantation. mBio 7, e01965–16 (2016).

Seekatz, A. M. et al. Restoration of short chain fatty acid and bile acid metabolism following fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Anaerobe 53, 64–73 (2018).

Brown, J. R.-M. et al. Changes in microbiota composition, bile and fatty acid metabolism, in successful faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridioides difficile infection. BMC Gastroenterol. 18, 131 (2018).

Mullish, B. H. et al. Microbial bile salt hydrolases mediate the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplant in the treatment of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Gut 68, 1791–1800 (2019).

Winston, J. A. et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) mitigates the host inflammatory response during Clostridioides difficile infection by altering gut bile acids. Infect. Immun. 88, e00045-20 (2020).

Monaghan, T. et al. Effective fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection in humans is associated with increased signalling in the bile acid-farnesoid X receptor-fibroblast growth factor pathway. Gut Microbes 10, 142–148 (2019).

Gadaleta, R. M. et al. Farnesoid X receptor activation inhibits inflammation and preserves the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 60, 463–472 (2011).

Wilson, A., Almousa, A., Teft, W. A. & Kim, R. B. Attenuation of bile acid-mediated FXR and PXR activation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Sci. Rep. 10, 1866 (2020).

McDonald, J. A. K. et al. Inhibiting growth of clostridioides difficile by restoring valerate, produced by the intestinal microbiota. Gastroenterology 155, 1495–1507 (2018).

Ott, S. J. et al. Efficacy of sterile fecal filtrate transfer for treating patients with clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology 152, 799–811 (2017).

Zuo, T. et al. Bacteriophage transfer during faecal microbiota transplantation in Clostridium difficile infection is associated with treatment outcome. Gut 67, 634–643 (2017).

Broecker, F. et al. Long-term changes of bacterial and viral compositions in the intestine of a recovered Clostridium difficile patient after fecal microbiota transplantation. Mol. Case Studies 2, a000448 (2016).

Staley, C. et al. Durable long-term bacterial engraftment following encapsulated fecal microbiota transplantation to treat clostridium difficile infection. mBio 10, e01586-19 (2019).

Goloshchapov, O. V. et al. Long-term impact of fecal transplantation in healthy volunteers. BMC Microbiol. 19, 312 (2019).

Moss, E. L. et al. Long-term taxonomic and functional divergence from donor bacterial strains following fecal microbiota transplantation in immunocompromised patients. PLoS ONE 12, e0182585 (2017).

Craven, L. et al. Allogenic fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease improves abnormal small intestinal permeability: a randomized control trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115, 1055–1065 (2020).

Pigneur, B. & Sokol, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation in inflammatory bowel disease: the quest for the holy grail. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 1360–1365 (2016).

Kim, K. O. & Gluck, M. Fecal microbiota transplantation: an update on clinical practice. Clin. Endosc. 52, 137–143 (2019).

Allegretti, J. R., Mullish, B. H., Kelly, C. & Fischer, M. The evolution of the use of faecal microbiota transplantation and emerging therapeutic indications. Lancet 394, 420–431 (2019).

Wilson, B. C., Vatanen, T., Cutfield, W. S. & O’Sullivan, J. M. The super-donor phenomenon in fecal microbiota transplantation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 2 (2019).

Kump, P. et al. The taxonomic composition of the donor intestinal microbiota is a major factor influencing the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation in therapy refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 47, 67–77 (2018).

Park, H. et al. The success of fecal microbial transplantation in Clostridium difficile infection correlates with bacteriophage relative abundance in the donor: a retrospective cohort study. Gut Microbes 10, 676–687 (2019).

Fuentes, S. et al. Microbial shifts and signatures of long-term remission in ulcerative colitis after faecal microbiota transplantation. ISME J. 11, 1877–1889 (2017).

Basson, A. R., Zhou, Y., Seo, B., Rodriguez-Palacios, A. & Cominelli, F. Autologous fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Transl Res. 226, 1–11 (2020).

Rinott, E. et al. Effects of diet-modulated autologous fecal microbiota transplantation on weight regain. Gastroenterology 160, 158–173 (2020).

Zeevi, D. et al. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell 163, 1079–1094 (2015).

Li, S. S. et al. Durable coexistence of donor and recipient strains after fecal microbiota transplantation. Science 352, 586–589 (2016).

Fischer, M. et al. Predictors of early failure after fecal microbiota transplantation for the therapy of clostridium difficile infection: a multicenter study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111, 1024–1031 (2016).

Gallo, A. et al. Fecal calprotectin and need of multiple microbiota trasplantation infusions in Clostridium difficile infection. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 1909–1915 (2020).

Hirten, R. P. et al. Microbial engraftment and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant for clostridium difficile in patients with and without inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25, 969–979 (2019).

Ponce-Alonso, M. et al. P782 A new compatibility test for donor selection for faecal microbiota transplantation in ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 11 (Suppl. 1), S480–S481 (2017).

Maier, L. et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 555, 623–628 (2018).

Mullish, B. H. et al. The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection and other potential indications: joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines. Gut 67, 1920–1941 (2018).

Imhann, F. et al. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut 65, 740–748 (2016).

Hong, A. S. et al. Proton pump inhibitor in upper gastrointestinal fecal microbiota transplant: a systematic review and analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 932–940 (2020).

Smillie, C. S. et al. Strain tracking reveals the determinants of bacterial engraftment in the human gut following fecal microbiota transplantation. Cell Host Microbe 23, 229–240 (2018).

Holvoet, T. et al. Assessment of faecal microbial transfer in irritable bowel syndrome with severe bloating. Gut 66, 980–982 (2017).

Leonardi, I. et al. Fungal trans-kingdom dynamics linked to responsiveness to fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) therapy in ulcerative colitis. Cell Host Microbe 27, 823–829 (2020).

Gogokhia, L. et al. Expansion of bacteriophages is linked to aggravated intestinal inflammation and colitis. Cell Host Microbe 25, 285–299 (2019).

Conceição-Neto, N. et al. Low eukaryotic viral richness is associated with faecal microbiota transplantation success in patients with UC. Gut 67, 1558–1559 (2018).

Ianiro, G. et al. Predictors of failure after single faecal microbiota transplantation in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: results from a 3-year, single-centre cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23, 337.e1–337.e3 (2017).

Sokol, H. Antibiotics: a trigger for inflammatory bowel disease? Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 956–957 (2020).

Keshteli, A. H., Millan, B. & Madsen, K. L. Pretreatment with antibiotics may enhance the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 565–566 (2017).

Ishikawa, D. et al. Changes in intestinal microbiota following combination therapy with fecal microbial transplantation and antibiotics for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23, 116–125 (2017).

Le Roy, T. et al. Comparative evaluation of microbiota engraftment following fecal microbiota transfer in mice models: age, kinetic and microbial status matter. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3289 (2019).

Ji, S. K. et al. Preparing the gut with antibiotics enhances gut microbiota reprogramming efficiency by promoting xenomicrobiota colonization. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1208 (2017).

Freitag, T. L. et al. Minor effect of antibiotic pre-treatment on the engraftment of donor microbiota in fecal transplantation in mice. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2685 (2019).

Tian, C. et al. Genome-wide association and HLA region fine-mapping studies identify susceptibility loci for multiple common infections. Nat. Commun. 8, 599 (2017).

Andeweg, S. P., Keşmir, C. & Dutilh, B. E. Quantifying the impact of human leukocyte antigen on the human gut microbiome. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.14.907196 (2020).

Levine, A. et al. Crohn’s disease exclusion diet plus partial enteral nutrition induces sustained remission in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 157, 440–450 (2019).

Svolos, V. et al. Treatment of active Crohn’s disease with an ordinary food-based diet that replicates exclusive enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology 156, 1354–1367 (2019).

Sabino, J., Lewis, J. D. & Colombel, J.-F. Treating inflammatory bowel disease with diet: a taste test. Gastroenterology 157, 295–297 (2019).

Ridaura, V. K. et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science 341, 1241214 (2013).

Chambers, E. S. et al. Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation, body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults. Gut 64, 1744–1754 (2015).

Augustyn, M., Grys, I. & Kukla, M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 5, 1–10 (2019).

Kastl, A. J., Terry, N. A., Wu, G. D. & Albenberg, L. G. The structure and function of the human small intestinal microbiota: current understanding and future directions. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 33–45 (2020).

Knights, D. et al. Complex host genetics influence the microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Genome Med. 6, 107 (2014).

Mizuno, S. et al. Bifidobacterium-rich fecal donor may be a positive predictor for successful fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 96, 29–38 (2017).

Acknowledgements

H.S. received funding from Agence National de Recherche (ANR-17-CE15–0019–01). N.R. and H.S. received support from the AFA (Association François Aupetit).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.D. researched data for the article, made a substantial contribution to the discussion of content, wrote the article and reviewed/edited the manuscript before submission. H.S. and N.R. researched data for the article, made a substantial contribution to the discussion of content and reviewed/edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.S. received unrestricted study grants from Danone, Biocodex, and Enterome, board membership, consultancy or lecture fees from Carenity, Abbvie, Astellas, Danone, Ferring, Mayoly Spindler, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Tillots, Enterome, Maat, BiomX, Biose, Novartis and Takeda, and is a co-founder of Exeliom bioscience. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology thanks G. Cammarota, B. Mullish and K. Madsen for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Danne, C., Rolhion, N. & Sokol, H. Recipient factors in faecal microbiota transplantation: one stool does not fit all. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18, 503–513 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00441-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00441-5

This article is cited by

-

Neutrophils: from IBD to the gut microbiota

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2024)

-

Intrahost evolution of the gut microbiota

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2023)

-

Effects of Different Preparation Methods on Microbiota Composition of Fecal Suspension

Molecular Biotechnology (2023)

-

Exploring rhizo-microbiome transplants as a tool for protective plant-microbiome manipulation

ISME Communications (2022)

-

Understanding and predicting the efficacy of FMT

Nature Medicine (2022)