Abstract

In the past decade, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become a leading cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, as well as an important risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of liver lesions, including simple steatosis, steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Although steatosis is often harmless, the lobular inflammation that characterizes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is considered a driving force in the progression of NAFLD. The current view is that innate immune mechanisms represent a key element in supporting hepatic inflammation in NASH. However, increasing evidence points to the role of adaptive immunity as an additional factor promoting liver inflammation. This Review discusses data regarding the role of B cells and T cells in sustaining the progression of NASH to fibrosis and HCC, along with the findings that antigens originating from oxidative stress act as a trigger for immune responses. We also highlight the mechanisms affecting liver immune tolerance in the setting of steatohepatitis that favour lymphocyte activation. Finally, we analyse emerging evidence concerning the possible application of immune modulating treatments in NASH therapy.

Key points

-

Chronic hepatic inflammation represents the driving force in the evolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to liver fibrosis and/or cirrhosis.

-

In both humans and rodents, NASH is characterized by B cell and T cell infiltration of the liver as well as by the presence of circulating antibodies targeting antigens originating from oxidative stress.

-

Interfering with lymphocyte recruitment and/or activation ameliorates experimental steatohepatitis and NASH-associated liver fibrosis.

-

In rodent models of NASH, lymphocyte responses contribute to sustained hepatic macrophage activation and natural killer T cell recruitment.

-

Alterations in regulatory T cell and hepatic dendritic cell homeostasis have a role in triggering immune responses during the progression of NASH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

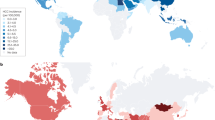

One of the consequences of the worldwide increase in overweight and obesity is the increased prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty live disease (NAFLD). At present, the global prevalence of NAFLD is estimated to be ~25%, ranging from 31–32% in the Middle East and South America to 24–27% in Europe and Asia, while the prevalence in Africa is ~14%1. NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of liver lesions that includes simple steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis and cirrhosis. Steatosis is the main feature in the majority of patients with NAFLD, and these patients generally do not have a substantial risk of liver-related adverse outcomes2. However, the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) — defined by the combination of liver steatosis, parenchymal damage (hepatocyte apoptosis and ballooning, and focal necrosis), lobular and/or portal inflammation and a variable degree of fibrosis — occurs in about 20–30% of patients with NAFLD, and can lead to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease2,3. The presence of hepatic fibrosis is the strongest predictor of disease-specific mortality in NASH, and the death rate ascribed to NASH-related cirrhosis is 12–25%3. End-stage liver disease due to NASH is also an increasingly common indication for liver transplantation3. Although progression of NAFLD to cirrhosis is more frequent among middle-aged (40–50 years old) and elderly people3, NAFLD among obese children is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis in adulthood4. A further feature of NAFLD progression is its association with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)5,6. NAFLD-related cirrhosis is a rising cause of HCC in Western countries, accounting for 10–34% of the known aetiologies for this cancer4. Nonetheless, growing evidence suggests that ~13–49% of all HCCs develop in patients with noncirrhotic NASH6. Together, these data indicate that NAFLD and NASH substantially contribute to the prevalence of cirrhosis and HCC worldwide. Such a scenario is forecast to worsen in the near future as a result of the expected rise in the prevalence of NAFLD7.

At present, lobular inflammation that characterizes NASH is considered the driving force in the disease progression to fibrosis, cirrhosis or HCC. Nonetheless, the presence of steatohepatitis is also associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney diseases and osteoporosis8, suggesting that liver inflammation might also represent a specific contributor to extrahepatic complications. The current view is that innate immune mechanisms represent a key element in supporting hepatic inflammation in NASH9,10. However, increasing evidence points to the role of lymphocyte-mediated adaptive immunity as an additional factor that promotes liver inflammation. This Review discusses data regarding the role of B cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in sustaining NASH progression, along with the possible mechanisms involved in triggering liver immune responses.

Innate immunity in NASH

Innate immune responses involved in NASH include the activation of resident Kupffer cells as well as the recruitment of leukocytes, such as neutrophils, monocytes, natural killer (NK) and natural killer T (NKT) cells, to the liver. In turn, these cells contribute to inflammation by releasing cytokines, chemokines, eicosanoids, nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species9,10. It is outside the scope of this review to discuss in detail the role of innate immunity in NALFD. Nonetheless, a few aspects deserve a short mention in relation to the interplay between the mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity. Several pro-inflammatory mechanisms operate in NAFLD and modulate its evolution9,10,11. For instance, as a result of insulin resistance, the excess of circulating free fatty acids and cholesterol directly stimulates Kupffer cells10,11,12. Within hepatocytes, free fatty acids not only cause endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipotoxicity13 but, by activating stress-responsive kinases (JNK1 and JNK2), favour the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and microvesicles, which stimulate macrophage activation13,14,15.

Oxidative stress is also a common feature of NAFLD and NASH16, and reactive oxygen species can stimulate inflammasome activation17. In addition, lipid peroxidation products generated by oxidative stress act as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in triggering Toll-like receptor signalling18. Moreover, studies have shown that gut dysbiosis associated with obesity promotes Kupffer cell activation through increased enteral absorption of bacterial products19. As a result, the release of chemokines (CC-chemokine ligand 1 (CCL1), CCL2 and CCL5) recruits infiltrating monocytes that further contribute to the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and to oxidative damage by differentiating into M1 activated macrophages20. In line with these findings, blocking CCL2 and CCL5 signalling ameliorated experimental NASH21 and reduced fibrosis evolution in a phase II clinical trial22. On the other hand, blocking anti-inflammatory mediators that control macrophage responses worsens NASH evolution23,24. Although these pro-inflammatory mechanisms might contribute to the evolution of NAFLD11, they do not explain why only a fraction of patients with steatosis develop hepatic inflammation and they do not fully account for the increase in the risk of extrahepatic complications among patients with NASH.

Lymphocyte involvement in NASH

One of the histological features of NASH is diffuse lobular infiltration by lymphocytes25. These cells are also an important component of periportal infiltrates associated with NASH ductular reactions26. In ~60% of patients with NASH, B cells and T cells form focal aggregates27, resembling ectopic lymphoid structures28 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the size and prevalence of these aggregates positively correlate with lobular inflammation and fibrosis scores27. Hepatic infiltration by B cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is also evident in different experimental models of NASH, in which it parallels with worsening parenchymal injury and lobular inflammation29,30,31,32,33. These T cells express the memory or effector markers CD25, CD44 and CD69, along with enhanced production of the cytokine LIGHT (also known as TNFSF14), indicating their functional activation29,30,33. Conversely, steatosis, parenchymal injury and lobular inflammation induced by long-term feeding with choline-deficient high-fat diet are greatly reduced in Rag1–/– mice, which lack mature B cells, T cells and NKT cells and are unable to mount adaptive immune responses30. The prevention of hepatic steatosis in Rag1–/– mice seems to be unrelated to metabolic abnormalities, insulin resistance or changes in gut microbiota, but instead is related to LIGHT-mediated stimulation of fatty acid uptake by hepatocytes30. Consistent with this finding, LIGHT deficiency improves insulin resistance, hepatic glucose tolerance and reduces liver inflammation in mice receiving NASH-inducing diets30,31.

Liver lymphocyte infiltration and ectopic lymphoid structures are also evident in association with severe steatohepatitis and fibrosis following the administration of a high-fat diet to mice carrying a hepatocyte specific deletion of TCPTP (T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase) (AlbCre;Ptpn2fl/fl), which is responsible for the nuclear dephosphorylation of the transcription factors signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), STAT3 and STAT5 (ref.33). According to this study, liver lymphocyte recruitment in AlbCre;Ptpn2fl/fl mice with NASH depends on the specific stimulation of hepatocyte STAT1 activity, which promotes production of the lymphocyte chemokine CXC-chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9)33. In this setting, reducing STAT1 but not STAT3 activation lowers CXCL9 expression, corrects the hepatic recruitment of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and ameliorates fibrosis33. Interestingly, greater expression of CXCL9 as well as STAT1 and STAT3 target genes fibrinogen-like 1 (FGL1) and lipocalin-2 (LCN2) is observed in the livers of obese patients with NAFLD compared with those without steatosis, whereas expression of FGL1 and CXCL9 further increases in the livers of obese patients with NASH33. CD4+ T cell recruitment in NASH also involves the hepatic production of vascular adhesion protein 1 (VAP1), an amino-oxidase constitutively expressed on human hepatic endothelium. Levels of circulating VAP1 are higher in patients with NASH than in patients with NAFLD or healthy control individuals, and are associated with increased severity of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis32.

Role of CD4+ T helper cells

The recruitment of CD4+ T helper cells to the liver is observed in several experimental models of steatohepatitis as well as in patients with NASH29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37. From a functional point of view, the polarization of CD4+ T cells as IFNγ-producing T helper 1 (TH1) cells has been documented along with increased expression of the TH1 transcription factor T-bet29,34 (Table 1). In the same vein, IFNγ-deficient mice develop less steatohepatitis and fibrosis than wild-type littermates when fed with a methionine–choline deficient (MCD) diet35. These findings are supported by clinical observations that both paediatric and adult patients with NASH are characterized by an increase in levels of liver and circulating IFNγ-producing CD4+ T cells36,37. Moreover, in adult patients with NASH, plasma IFNγ levels positively correlate with the number and size of hepatic lymphocyte aggregates as well as with the severity of fibrosis27.

In response to inflammatory stimuli, CD4+ T cells can also differentiate to type 17 T helper (TH17) cells, which are characterized by the expression of the nuclear receptor retinoic acid-related orphan receptor-γt and by the production of IL-17 and, to a lesser extent, IL-21, IL-22, IFNγ and TNF38. The IL-17 family (IL-17A–F) is a group of structurally related cytokines that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of both acute and chronic liver injury39. The possible involvement of TH17 cells in NASH emerges from the observation that liver and circulating TH17 cells are increased in patients with NAFLD and/or NASH along with levels of TH1 cells40. Interestingly, the progression from NAFLD to NASH is associated with a pronounced accumulation of TH17 cells in the liver, and these changes normalize 1 year after bariatric surgery in parallel with improvement in NASH40. In rodents receiving high-fat or MCD diets, a deficiency of IL-17A, IL-17F or IL-17A receptor (IL-17RA) results in increased steatosis but reduced steatohepatitis41,42. This uncoupling of steatosis from steatohepatitis involves a decrease in T cell and macrophage recruitment to the liver and reduced production of pro-inflammatory mediators42. Similarly, TH17 cells and IL-17A are required for the development of fat inflammation, insulin resistance and steatohepatitis in mice overexpressing the hepatic unconventional prefoldin RPB5 interactor 1 (URI), which is postulated to couple nutrient surplus to inflammation43. In these animals, the capacity of inflammatory cells to respond to IL-17 seems to be critical, as genetic ablation of IL-17RA in myeloid cells prevents development of NASH43. On the other hand, IL-17+CD4+ T cells are unchanged in AlbCre;Ptpn2fl/fl mice with NASH despite extensive liver infiltration by CD4+ TH1 cells and activated CD8+ T cells33.

The complex role of TH17 cells in NASH is further evidenced by time-course experiments in mice receiving the MCD diet. In these animals, the prevalence of liver TH17 cells fluctuates during disease evolution, peaking at the onset of steatohepatitis and then in the late phase of the disease44. Opposite variations are evident for intrahepatic IL-22-producing CD4+ T cells (TH22), which are prevalent between the first and second expansion of TH17 cells44. Extensive hepatic infiltration of TH22 cells is also evident in MCD-fed IL-17-deficient (Il17−/−) mice, which display milder steatohepatitis than wild-type MCD-fed mice44. These observations and the hepatoprotective action ascribed to IL-22 (ref.39) suggest a possible antagonist action between TH17 and TH22 lymphocytes in modulating NASH. Indeed, IL-17 and IL-22 deficiencies have been shown to exert opposite effects in the development of experimental fibrosis39. Moreover, in vitro, hepatocyte supplementation with IL-17 exacerbates lipotoxicity induced by palmitate, while IL-22 prevents it by inhibiting JNK1 and JNK2 through the action of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). However, the effects of IL-22 are evident only in the absence of IL-17, as IL-17 upregulates the PI3K–AKT antagonist phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)44. Consistently, Il-17−/− mice fed with the MCD diet display decreased activation of liver JNK1 and JNK2 and reduced expression of PTEN compared with wild-type mice44. Thus, the actual impact of TH17 cell responses in NASH evolution is probably influenced by the concomitant differentiation of CD4+ TH22 cells as well as by the fact that γδ T cells also account for the production of IL-17A in livers with steatohepatitis45. Altogether, these data indicate that hepatic infiltration by TH1 cells and possibly CD4+ TH17 cells can substantially contribute to the mechanisms supporting lobular inflammation during NASH evolution (Table 1).

Role of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells

The evolution of NAFLD and NASH in both humans and mice is accompanied by an increase in the prevalence of activated cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in the liver29,30,33,46. These cells are mainly recruited in response to signals mediated by IFNα and they promote insulin resistance and liver glucose metabolism in mice receiving a high-fat diet46. In the same way, β2m–/– mice lacking CD8+ T cells and NKT cells are protected from both steatosis and NASH when fed with a choline-deficient high-fat diet, which is associated with reduced production of LIGHT by CD8+ T cells and NKT cells30. The selective ablation of CD8+ T cells is also effective in ameliorating steatohepatitis in wild-type mice receiving a high-fat, high-carbohydrate (HF–HC) diet47, suggesting an actual role in the pathogenesis of NASH (Table 1). Nonetheless, additional studies are required to better characterize CD8+ T cell function in relation to disease progression.

Role of B cells

In addition to T cells, B cells are detectable within inflammatory infiltrates in liver biopsy samples from patients with NASH27,33. In mouse models of NASH, we observed that B cells were activated in parallel with the onset of steatohepatitis and matured to plasmablasts and plasma cells27. Mouse liver B cells mainly consist of bone-marrow-derived mature B220+IgM+CD23+CD43– B2 cells resembling spleen follicular B cells. However, a small fraction of B220+IgM+CD23–CD43+ B1 cells is also detectable48. The functions of these two B cell subsets are not overlapping. On antigen stimulation, B1 cells mature in a T cell-independent manner to plasma cells producing IgM natural antibodies49. Natural antibodies are pre-existing germline-encoded antibodies with a broad specificity to pathogens, but which are also able to crossreact with endogenous antigens, such as oxidized phospholipids and proteins adducted by the end products of lipid peroxidation49. Conversely, the B2 subset requires T helper cells to proliferate and undergo antibody isotype class switching, which leads to plasma cells producing highly antigen-specific IgA, IgG or IgE49.

In mice with NASH, the B cell response involves CD43–CD23+ B2 cells and is accompanied by upregulation of the hepatic expression of B cell-activating factor (BAFF)28, one of the cytokines that drives B cell survival and maturation49. Interestingly, circulating levels of BAFF are higher in patients with NASH than in those with simple steatosis, and levels correlate with the severity of steatohepatitis and fibrosis50. Selective B2 cell depletion in mice overexpressing a soluble form of the BAFF–APRIL receptor transmembrane activator and cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI) prevents plasma cell maturation. Furthermore, these mice have mild steatohepatitis and less fibrosis when receiving NASH-inducing diets27. The contribution of B cells to the progression of NASH can be ascribed to the production of pro-inflammatory mediators51 as well as to their antigen-presenting capabilities52 (Table 1). In this respect, B cell activation in patients with NASH is associated with upregulation of major histocompatibility class II molecules in plasmablasts and precedes the recruitment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to the liver, whereas interfering with B2 cells reduces TH1 cell activation of liver CD4+ T cells and IFNγ production27. These observations are consistent with previous studies indicating that B cells contribute to autoimmune hepatitis53 and liver fibrogenesis48,54.

The pro-fibrogenic role of B cells is postulated to involve the production of pro-inflammatory mediators that stimulate hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and liver macrophages54. In turn, activated HSCs support liver B cell survival and maturation to plasma cells by secreting retinoic acid54. So far, the clinical relevance of these findings has not been investigated in detail. However, serum levels of IgA are more frequently elevated among patients with NASH than in patients with simple steatosis, and are also an independent predictor of advanced liver fibrosis55. Such upregulation of IgA directly relates to steatohepatitis given that IgA-producing plasma cells are detectable in the livers of AlbCrePtpn2fl/fl mice with NASH fed a high-fat diet33. Improved characterization of the origin and antigen specificity of NAFLD-related IgA might enable their use as possible serological markers for disease progression to cirrhosis.

Notably, the involvement of adaptive immunity in NASH (as outlined earlier) has many analogies with the data concerning the role of B cells and T cells in supporting insulin resistance and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) inflammation in obesity56. In fact, obesity in both rodents and humans is associated with the expansion and activation of VAT CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, whereas T cell blockage or IFNγ neutralization reduce fat inflammation and insulin resistance56. Similarly, B cells isolated from the VAT of obese mice show increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promote T cell and macrophage activation, while a lack of B cells improves fat inflammation and insulin resistance56. These data might explain why, in several experimental models of NASH, interference with adaptive immunity ameliorates liver lipid metabolism and steatosis by improving insulin resistance. Altogether, these data suggest the possibility that, in patients with metabolic syndrome, lymphocytes might support VAT and liver inflammation through similar mechanisms.

Oxidative stress and NASH immunity

A key issue for understanding the contribution of adaptive immunity in the evolution of NAFLD to NASH is the characterization of the antigenic stimuli that trigger lymphocyte responses. As mentioned earlier, oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation are common features of NAFLD and NASH16. Oxidized phospholipids and reactive aldehydes generated during lipid peroxidation, such as malondialdehyde, not only act as DAMPs in activating hepatic inflammation57 but also form antigenic adducts with cellular macromolecules known as oxidative stress-derived epitopes (OSEs)58. OSEs are implicated in the stimulation of immune reactions responsible for plaque evolution in atherosclerosis58 and in the breaking of self-tolerance in several autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus59. OSEs also include condensation products generated by the interaction between malondialdehyde and acetaldehyde, known as malondialdehyde–acetaldehyde adducts (MAA)60.

The involvement of oxidative stress in driving NAFLD-associated immune responses came from observations that elevated titres of anti-OSE IgG were detectable in ~40% of adult patients with NAFLD or NASH in two unrelated cohorts28,61 and in 60% of children with NASH62. In particular, anti-OSE IgGs in adults with NAFLD or NASH target the cyclic MAA adduct methyl-1,4-dihydroxypyridine-3,5-dicarbaldehyde61. In patients investigated so far, high titres of anti-OSE IgGs are associated with the severity of lobular inflammation62, the prevalence of intrahepatic B cell and/or T cell aggregates28 and are an independent predictor of fibrosis61. The contribution of oxidative stress in stimulating adaptive immunity in NASH is further supported by animal data demonstrating that humoral and cellular responses against OSEs are linked with hepatic inflammation and parenchymal injury in a dietary rat model of NAFLD as well as in mice with NASH induced by the MCD diet29,63. In these settings, the increase in titres of anti-OSE IgG accompanies the maturation of liver B2 cells to plasma cells27,29, whereas reducing lipid peroxidation by supplementation with N-acetylcysteine or B2 cell depletion prevents antibody responses27,63. Conversely, mice preimmunized with malondialdehyde-adducted proteins, which also contain the MAA epitopes, before receiving the MCD diet have enhanced liver lymphocyte infiltration and more severe parenchymal injury, lobular inflammation and fibrosis29. Such an effect involves TH1 cell activation of liver CD4+ T cells, which, by releasing CD40 ligand (CD154) and IFNγ, promote M1 activation of hepatic macrophages29. These results are consistent with clinical observations showing a positive correlation between anti-OSE IgG and circulating IFNγ levels in human patients with NASH27 and strongly indicate that, by promoting OSE formation, hepatocyte oxidative stress represents an important trigger for both humoral and cellular immune responses in the liver (Fig. 2).

Liver dendritic cells and other antigen-presenting cells (APCs) present oxidative stress-derived epitopes (OSE) to CD4+ T helper (TH) cells in the context of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) molecules. This signal, together with enhanced expression of costimulatory molecules such as OX40, leads to the activation of CD4+ T cells and their TH1 cell or TH17 cell polarization. CD4+ TH cells also support both cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses and B cell maturation of plasma cells secreting anti-OSE IgG. In turn, B cells can promote immune-inflammatory processes by antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells and by producing inflammatory cytokines. IFNγ and TH1 cell cytokines also stimulate liver macrophages to release M1 pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-12, CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and CXC-chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9)) that further contribute to recruiting monocytes and lymphocytes. Macrophages and dendritic cells also release B cell stimulating cytokines such as B cell-activating factor (BAFF), which are critical for B cell maturation to plasma cells. IL-15 produced by both hepatocytes and liver macrophages favours the survival of CD8+ T cells and, together with CXCL16, is implicated in promoting liver natural killer T (NKT) cell differentiation and survival. NKT cells and CD8+ T cells can further contribute to steatohepatitis through the secretion of LIGHT and IFNγ. TCR, T cell receptor.

In contrast to the observations implicating OSE-dependent immune responses in the pathogenesis of NASH, T15 natural IgM crossreacting with oxidized phosphatidylcholine ameliorates NASH in LDL receptor-deficient (Ldlr–/–) mice receiving an HF–HC diet64. This effect seems to be related to the prevention of the pro-inflammatory activation of liver macrophages consequent to their engulfment of cholesterol-rich oxidized LDLs64. An increase in IgM targeting oxidized LDL also accounts for the improvement in steatohepatitis observed in HF–HC-fed Ldlr–/– mice lacking the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin G (Siglec-G), a negative regulator of B1 cells65. Liver prevalence of B1 cells, as well as circulating anti-OSE IgM titres, are not appreciably modified during the evolution of experimental NASH27,29. Conversely, a study reported that levels of IgM targeting OSE-modified LDLs are lower in patients with NAFLD than in healthy control individuals66. The same study also showed that IgM titres against one of the OSE structures (P1 mimotope) inversely correlate with markers of obesity, systemic inflammation and liver damage66.

These opposite actions of anti-OSE IgG and IgM show many analogies to that observed in atherosclerosis67 and obesity-associated VAT inflammation68. Thus, B1 and B2 cell responses might exert antagonist activities in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, with IgG-producing B2 cells being involved in promoting pro-inflammatory mechanisms, and IgM from B1 cells having a protective action (Table 1). In this scenario, reduced levels of anti-OSE IgM in combination with stimulation of OSE-responsive B2 cells and T cells might exert a synergistic action in the development of NASH-associated immune responses.

Innate and adaptive cell interplay

A role for adaptive immunity in NASH is compatible with observations concerning the importance of innate responses in the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. In fact, the network of cytokines generated by TH1, TH17 and CD8+ lymphocytes provide a potent stimulus for the activation of M1 hepatic macrophages (Table 1) which, in turn, support lymphocyte functions through the release of a variety of mediators including IL-12, IL-23, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 (ref.20) (Fig. 2). Lymphocyte-stimulated secretion of IL-15 and IL-18 by macrophages might also promote NK cell activation, which has been shown to modulate mechanisms of steatohepatitis and fibrogenesis69.

Another component of innate immunity implicated in NAFLD and NASH is NKT cells, which are a T cell subset characterized by the coexpression of T cell receptor and NK cell surface receptors (NK1.1 in mice and CD161 or CD56 in humans)70. NKT cells recognize lipid antigens presented by CD1d-expressing antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and secrete a variety of cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, IFNγ and TNF) that can promote TH1, TH2 and CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cell activities70. Thus, NKT cells can both stimulate and suppress immune and/or inflammatory responses. NKT cell prevalence within the liver varies during the course of the disease as signals mediated by IL-12 and the T cell mucin domain-3/galectin-9 dyad reduce the numbers of NKT cells in steatosis and during the early phases of steatohepatitis71,72. Conversely, NKT cell expansion is evident in advanced NASH30,73 concomitant with enhanced secretion of LIGHT, IFNγ, and IL-17A30,74. Interfering with NKT cells during advanced NASH effectively improves hepatic parenchymal injury, inflammation and fibrosis in different experimental models of the disease30,47,74,75. The large majority (95%) of liver NKT cells is represented by type I or invariant NKT (iNKT) cells70. Interestingly, the lack of iNKT cells in Jα18–/– mice or their inhibition in wild-type animals treated with the retinoic acid receptor-γ agonist tazarotene reduces CD8+ T cell infiltration in the livers of these mice with NASH75, suggesting a strict interplay between cytotoxic T cells and iNKT cells in the mechanisms supporting steatohepatitis (Fig. 2). CXCL16 and IL-15 have been proposed to expand the pool of liver NKT cells in NASH76,77, acting as a chemoattractant and differentiation and/or survival factor, respectively78. We have observed that boosting anti-OSE immunity in mice with NASH stimulates an early expansion of the NKT pool by upregulating hepatic expression of IL-1529. On the other hand, mice deficient for IL-15 or IL-15 receptor-α (IL-15Rα) are depleted of intrahepatic CD4+, CD8+ and NKT cells and, when receiving a high-fat diet, show milder steatosis and lobular inflammation than wild-type littermates79. Thus, IL-15 might act as a possible mediator in the signal network linking adaptive and innate immune cell responses during the evolution of steatohepatitis (Fig. 2).

Mechanisms promoting adaptive immunity

Under physiological conditions the liver has important immunosuppressive functions inducing tolerance to autoantigens and antigens from ingested food or commensal bacteria80,81. These actions are mediated by a complex network of signals involving professional APCs, such as Kupffer cells and dendritic cells, as well as nonprofessional APCs including hepatocytes, hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells and HSCs81. These cells present antigens to T cells in a way that leads to T cell apoptosis, anergy or differentiation into CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Treg cells81. Additional immunosuppressive signals can also derive from NKT and NK cells and myeloid suppressor cells81. In view of the specificity of the liver environment, the mechanisms responsible for subverting such tolerogenic milieu to trigger adaptive immunity in NASH remain underexplored.

Dendritic cells

Hepatic dendritic cells (HDCs) have an important role in orchestrating liver immunity. HDCs account for <1% of total liver myeloid cells82,83 and are distinguished into plasmacytoid and myeloid (or classical) subsets, with the latter further subgrouped into type 1 and type 2 HDCs82,83. During homeostasis, HDCs contribute to the tolerogenic environment of healthy livers83,84,85. However, the onset of NASH is associated with expansion of myeloid HDCs and acquisition of the capacity to specifically stimulate CD4+ T cells82. This response involves a subset of HDCs with high lipid content86 and is probably triggered by Toll-like receptor 4 stimulation induced by HMGB1 protein released by damaged or dying hepatocytes87. However, mice lacking type 1 myeloid HDCs display increased susceptibility to steatohepatitis88, suggesting that different HDC subsets might be involved in disease evolution. In fact, characterization of myeloid HDCs expanding in NASH reveals that a substantial fraction of these cells expresses the fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 (CX3C-chemokine receptor 1) along with monocyte markers, and produces high levels of TNF89, suggesting a role for monocyte-derived inflammatory dendritic cells in steatohepatitis90. In addition, interfering with CX3CR1 expression lowers the number of inflammatory HDCs and reduces both TNF production and hepatocyte death89. Although HDC expansion and/or activation probably have key roles in stimulating the adaptive immune response in NASH, some aspects of this mechanism need further clarification. A study reported that an unspecific HDC depletion (by administration of diphtheria toxin in transgenic mice expressing the toxin receptor under the control of the dendritic cell marker CD11c (CD11c-DTR)) worsens NASH-associated hepatic inflammation and liver injury91. These paradoxical results might be explained by the ablation of protective type 1 myeloid HDCs88 or of other cells expressing CD11c, such as NK cells. Indeed, depletion of NK1+DX5+NKp46+ NK cells worsens hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in mice receiving the MCD diet92.

A critical aspect of HDC action in NASH immunity involves antigen presentation to CD4+ T helper cells, which, in turn, supports cytotoxic CD8+ T cell and B cell responses. In these settings, T cell receptor-mediated signals are modulated by additional signals provided by costimulatory and coinhibitory molecules of the B7 and TNF families93. Although the activity of costimulatory molecules has an important role in triggering T cell responses in VAT during obesity and in modulating anti-OSE immunity in atherosclerosis93,94, their actual role in NASH is still poorly characterized. In this respect, a study from 2018 (ref.95) has shed some light on the involvement of OX40 (CD134) in NASH. OX40 is a costimulatory molecule of the TNF family that is largely expressed on activated T cells in both mice and humans96. Upon ligation by OX40 ligand (OX40L, CD252) which is present on APCs, OX40 promotes T cell responses96. In mice receiving a high-fat diet, OX40 and OX40L are upregulated in the livers of mice with NASH, and OX40 deficiency selectively lowers hepatic CD4+ T cell recruitment and TH1 and TH17 cell differentiation, ameliorating steatosis, and reducing the release of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase and the prevalence of M1 macrophages95. Interestingly, levels of soluble OX40 are also increased in the plasma of patients with NASH, positively correlating with the severity of steatohepatitis95. These data, along with the observation that OX40 promotes insulin resistance and obesity-induced CD4+ T cell responses in VAT97, suggest that OX40 and possibly other costimulatory molecules can critically influence adaptive immunity in NASH.

Regulatory T cells in the liver

Treg cells in the liver have a key role in regulating liver immune tolerance by directly suppressing the proliferation and effector functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells through signals mediated by coinhibitory molecules such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) or by secreting IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β80. Treg cells are a subset of CD4+ T cells that express the transcription factor Forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) and originate either in the thymus or peripheral organs. Within the liver, immunosuppressive HDCs have an important role in directing naive CD4+ T cells to Treg cell differentiation by expressing membrane-bound programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and by releasing IL-10 and kynurenine80. Treg cell analysis shows that levels of resting Treg cells are lower both in the circulation and the liver of patients with NAFLD than in healthy control individuals40. Such a reduction is more pronounced in patients with steatohepatitis than in patients with simple steatosis, paralleling TH1 and TH17 T cell expansion40. Conversely, levels of activated Treg cells in the liver are unchanged in NAFLD despite an increase in the circulating levels of these cells40. As a result, the liver TH17:resting Treg ratio is able to discriminate patients with NASH from those with steatosis only, correlating with plasma levels of cytokeratin 18 (ref.40) (a marker of hepatocyte death)98. Interestingly, VAT inflammation in obesity is also associated with Treg depletion and TH17–Treg cell imbalance56.

At present, the mechanisms responsible for reducing the numbers of Treg cells in NAFLD are poorly characterized. In fatty livers, Treg cells are more susceptible to apoptosis in response to oxidative stress than in nonfatty livers99. Additional mechanisms, including the impairment of immunosuppressive functions of HDCs or interference with Treg cell differentiation signals mediated by IL-33, might also be involved100. Imbalances in the secretion of adipokines by adipose tissue are additional factors that can affect Treg cells, as increased leptin production in obesity has been shown to reduce Treg cell differentiation whereas it stimulates dendritic cell activation and TH1 and TH17 polarization of CD4+ T cells101. The actual relevance of Treg cells in the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis currently remains uncertain in view of the conflicting data obtained in experimental studies. Reducing numbers of Treg cells in mice via combined deficiency of the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 worsens adipose tissue inflammation and steatohepatitis induced by feeding with a high-fat diet102. By contrast, levels of Treg cells in the liver are unchanged in different models of NASH despite extensive lymphocyte TH1 and TH17 cell activation33,44.

Extrahepatic factors

Along with the changes in HDCs and Treg cells, studies in rodent models of NASH indicate that additional factors can affect hepatic immune tolerance. For instance, chronic liver inflammation induced by chronic CCl4 treatment or the MCD diet abolishes the capacity of Kupffer cells to promote liver Treg cell expansion and tolerogenic responses, favouring instead the immunogenic stimulation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells103. Thus, by acting at the same time as DAMPs and immunogenic antigens, OSEs generated within hepatocytes can both dampen hepatic immune tolerance and promote their own presentation to lymphocytes by APCs, triggering both B cell and T cell activation18,58 (Fig. 2).

Additional mechanisms contributing to the impairment of liver immune tolerance might involve alterations to the gut microbiota (dysbiosis), which is evident in some patients with NAFLD and NASH19,104. During homeostasis, Kupffer cells and hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells are known to respond to low levels of endotoxins in the portal blood by releasing IL-10 (ref.80). However, intestinal bacterial overgrowth and increased endotoxin reabsorption into the portal circulation can subvert the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive milieu by stimulating pro-inflammatory Kupffer cell activation, leading to a worsening of steatohepatitis105,106. Bacterial products can also directly promote hepatic CD8+ T cell accumulation and/or activation by inducing type I interferon production46. Further mechanisms by which dysbiosis might contribute to NASH-associated immune responses involve alterations in gut tolerance to autoantigens107 and the generation of short-chain fatty acids (such as acetate, propionate and butyrate) from carbohydrate fermentation19,83. Short-chain fatty acid production is increased in patients with NAFLD19,104, and increased faecal propionate and acetate levels are associated with reduced numbers of resting Treg cells as well as with a higher TH17:resting Treg cell ratio in the peripheral blood of patients with NAFLD108.

Altogether, the available evidence indicates that livers from patients with NAFLD might lose their tolerogenic environment in response to a variety of intrahepatic and extrahepatic stimuli (Fig. 3). In these circumstances, antigen presentation by both professional and nonprofessional APCs, together with the upregulation of costimulatory signals and an inflammatory cytokine milieu, are the background for effective B cell and T cell stimulation.

During the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, the combined action of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released by damaged hepatocytes, oxidative stress-derived epitopes (OSEs) and pro-inflammatory mediators affects the tolerogenic action of liver dendritic cells, Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells. These changes contribute to a reduction in liver regulatory T (Treg) cells and favours the expansion and activation of dendritic cells. Alterations in the gut–liver axis due to dysbiosis and obesity-related changes in the adipokine network are additional factors that affect liver immune tolerance. As a result, enhanced antigen presentation to lymphocytes associated with increased expression of costimulatory molecules leads to the development of both cellular and humoral immune responses. APC, antigen presenting cell; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; TH cell, T helper cell.

Immunity and NAFLD-associated HCC

NAFLD has emerged as an important risk factor for HCC, with an incidence of HCC of ~0.4% in patients with NAFLD5. HCCs commonly develop on a background of chronic liver inflammation and are often associated with cirrhosis5,6. In these settings, chronic necroinflammatory liver damage promotes compensatory hepatocyte growth allowing the emergence of mutated cell clones that are further supported in their growth by inflammatory mediators109. Consistent with these mechanisms, steatohepatitis not only promotes carcinogen-induced HCCs110 but also leads to the spontaneous development of HCCs in mice receiving a choline-deficient diet30,111. In a similar manner, in transgenic mice overexpressing the urokinase plasminogen activator, the URI or the MYC oncogene, induction of NASH (via a high-fat diet) leads to HCC43,112,113. Unsurprisingly, adaptive immune responses involved in liver injury and inflammation also contribute to NAFLD-associated HCC. In fact, the lack of CD8+ T cells and NKT cells as well as interference with LIGHT or IL-17 ameliorates both the severity of steatohepatitis and the prevalence of HCC in these mouse models30,43.

However, the overall picture is still quite confused owing to conflicting results. For instance, despite the association of CD4+ TH1 and TH17 cells with NASH inflammatory mechanisms27,33,35,41,42,43,44,95, one study has shown that the selective depletion of CD4+ T cells accelerates HCC growth when NASH is induced in mice with hepatocyte-specific overexpression of MYC113. In these animals, CD4+ T cell loss has been ascribed to mitochondrial oxidative stress resulting from disrupted lipid metabolism113. However, how these data relate to the expansion of CD4+ T cells observed in many different models of NASH27,33,35,41,42,43,44,95, and how CD4+ T cell depletion can favour tumour growth, is not clear.

In a similar manner, the development of NASH-associated HCCs in AlbCre;Ptpn2fl/fl mice carrying combined STAT1–STAT3 overactivation is not corrected by blocking STAT1 activity, despite a dramatic reduction in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell recruitment and activation33. On the other hand, in the same strain, blocking STAT3 prevents HCC without affecting immune responses33. Further conflicting data have been obtained with more specific reference to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. For example, CD8+ T cell ablation promotes HCC in urokinase plasminogen activator-overexpressing mice receiving a high-fat diet114, whereas the lack of CD8+ T cells and NKT cells reduces tumour development in β2m–/– mice receiving the choline-deficient, HF–HC diet30. These discrepancies might be related to differences in the experimental models as well to the dual role played by immune mechanisms in HCC development. By supporting inflammation, adaptive immunity might contribute to cancer cell growth by promoting STAT3 activity in tumour cells. Nonetheless, tumour infiltrating T cells also perform important antitumoural actions that need to be overcome to allow cancer cell growth109. For instance, in both humans and mice, advanced NASH is characterized by the accumulation of IgA-producing plasma cells that suppress antitumour cytotoxic CD8+ T cells through the expression of PD-L1 and IL-10, thus favouring HCC emergence114. Similarly, genetic or pharmacological interference with IgA-producing plasma cells or PD-L1 blockade restores the cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells and attenuates hepatic carcinogenesis114. These data not only suggest a complex role of adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of NAFLD-associated HCC, but also highlight the unresolved issue of how adaptive immunity is modulated at different stages of NASH evolution and whether immune checkpoints might affect disease progression.

Targeting adaptive immunity in NASH

The current development of therapies for NAFLD and NASH has mainly focused on modulating metabolic disturbances, oxidative stress and innate immunity115. Our knowledge regarding the involvement of B cells and T cells in inflammatory mechanisms of NASH is still incomplete, but a few studies have addressed the possibility of interfering with adaptive immunity as a novel approach for treating NASH. For instance, from the observation that the adhesion protein VAP1 promotes liver lymphocyte recruitment in NASH, VAP-1 neutralizing antibodies (BTT-1029) have been shown to reduce the severity of steatohepatitis and delay the onset of fibrosis in different experimental models of NASH32. However, this effect might also involve inhibition of the amine oxidase activity of VAP1 (ref.116), which can promote cytotoxicity and oxidative stress by generating aldehydes and hydrogen peroxide. Studies have highlighted the role of B cells in NASH progression27 as well as the association between circulating levels of the B cell cytokine BAFF and the severity of steatohepatitis and fibrosis50. Notably, treatment with the BAFF-neutralizing monoclonal antibody Sandy-2 prevents hepatic B2 cell responses and ameliorates established NASH in mice27. The BAFF antagonist belimumab is already approved for the treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematous, and several other molecules with a similar action are under trial for the treatment of other B cell-driven autoimmune diseases117. Thus, expanding our knowledge on the contribution of B cells to the pathogenesis of NASH might lead to the use of some of these agents as therapeutic approaches for those patients with NASH in whom adaptive immune mechanisms contribute to hepatic inflammation.

A different approach for targeting adaptive immunity in NASH relies on the possible applications of immunomodulatory treatments capable of stimulating Treg cells. For instance, the oral or nasal administration of antibodies targeting the T cell receptor-associated molecule CD3 has proved effective in ameliorating mouse autoimmune responses and atherosclerosis by inducing a specific subset of Treg cells that express latency-associated peptide (LAP)118,119. Accordingly, oral administration of the murine anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies OKT3 plus β-glucosylceramide to obese leptin-deficient ob/ob mice induces LAP+ Treg cells and decreases adipose tissue inflammation along with liver steatosis and transaminase release120. In humans, OKT3 antibodies effectively downmodulate TH1–TH17 cell responses with a concomitant increase in the expression of Treg cell markers121. Furthermore, a single-blind randomized placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial has shown that oral OKT3 administration to patients with biopsy-proven NASH and type 2 diabetes mellitus ameliorates alanine aminotransferase release, and improves blood glucose and insulin levels121. Treg cell stimulation can also be achieved by the oral administration of hyperimmune cow colostrum (Imm124-E), which improves insulin resistance and liver injury in ob/ob mice122. However, despite Imm124-E enhancing metabolic control in patients with NAFLD, it does not improve hepatic damage123. Altogether, these preclinical and clinical data indicate that modulation of Treg cells has the potential to suppress inflammation in NASH. However, these studies are limited by the choice of the experimental models and the small number of patients investigated. Moreover, none of these studies has addressed the changes in immunological reactions associated with NASH.

The oral administration of antigens, a process known as oral tolerance, is emerging as an alternative way to downmodulate specific immune responses124. Immune cells of the intestinal mucosa and gut-associated lymphoid tissues are known to be implicated in controlling immune reactions to food-derived antigens and gut microbiota, but this ability might also be exploited to induce immune tolerance to specific antigens118,124. Oral tolerance has been used to prevent food allergies and coeliac disease through the stimulation of Treg cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells124. At present, the only report addressing the effects of oral tolerance in NASH concerns the observation that dietary supplementation of ob/ob mice with proteins extracted from the liver of either ob/ob or wild-type mice improves insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis without affecting transaminase release and levels of circulating inflammatory cytokines125. Additional studies in this field are urgently needed, as induction of oral tolerance through the administration of suitable molecules or by modulating the gut microbiota might represent an effective approach for achieving long-term control of the immune and inflammatory mechanisms underlying NAFLD evolution.

Conclusions

So far, the available data point to the involvement of adaptive immunity in the evolution of NAFLD. CD4+ TH1 and TH17 cells are recruited within the liver at the onset of steatohepatitis; TH1 cytokines, and possibly TH17 cytokines, generated by these lymphocytes provide a potent stimulus for hepatic macrophages, further driving chronic liver inflammation. In turn, macrophages contribute to lymphocyte recruitment and/or activation through the release of IL-12, IL-23 and lymphocyte chemokines. In addition, effector CD8+ T cells and B2 cells are also involved, although the relative role of these cells is still not fully defined. At present, oxidative stress represents the best characterized trigger of NASH-associated immune reactions. In this setting, the observation that anti-OSE IgGs are an independent risk factor for NASH progression to fibrosis61 suggests the possibility that elevated levels of circulating anti-OSE IgGs can identify a subset of patients with NASH in whom adaptive immunity might have a key role in promoting steatohepatitis.

Nonetheless, several unresolved issues remain in understanding the mechanisms by which adaptive immunity can contribute to NAFLD evolution (Box 1). For instance, evidence suggesting that B cells and CD4+ T cells infiltrating the liver in NASH originate from mesenteric lymph nodes and inflamed mesenteric adipose tissue126,127 raises the question of how gut–liver interactions influence NASH-associated adaptive immunity. In this setting, an additional question concerns the mechanism by which NAFLD affects the liver tolerogenic milieu to favour OSE presentation by APCs to B cells and T cells. Emerging evidence suggests the possibility that dysbiosis might have a role in this process. The characterization of these mechanisms would shed some light on the factors that influence the interindividual variability in the onset of adaptive immune reactions among patients with NAFLD or NASH. In a similar manner, more information is required to better characterize the interplay between B cells, T cells and other liver myeloid cells including macrophages, NK and NKT cells as well as the possible interactions with γδ T cells, innate lymphoid cells and mucosal-associated invariant T cells45,128,129,130,131,132.

Another aspect of NAFLD-related immunity that deserves attention is the similarity of the antigens involved with those implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis58. In this respect, experimental studies have shown that Ldlr–/– mice fed a HF–HC diet, an established rodent model of atherosclerosis, also develop NASH. Notably, removing OSE-modified LDLs ameliorates both the diseases57,66,67. Given that NAFLD is increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases133, establishing whether anti-OSE antibodies might identify patients with NAFLD or NASH with specific risks for cardiovascular complications could be important.

In conclusion, clarifying the role of adaptive immunity in NAFLD and NASH will not only enhance our understanding of disease pathogenesis, but will also enable identification of biomarkers that are able to discriminate patients with NAFLD at risk of developing NASH and/or patients with NASH at high risk of progression to cirrhosis or extrahepatic complications. New insights into the role of immune mechanisms will also provide the rationale for novel treatments based on the modulation of liver tolerogenic responses and/or the application of a wide array of molecules already being studied in other conditions that are characterized by impaired immune regulation or autoimmunity.

References

Younossi, Z. et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 11–20 (2018).

Rinella, M. E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA 313, 2263–2273 (2015).

Lindenmeyer, C. C. & McCullough, A. J. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease — an evolving view. Clin. Liver Dis. 22, 11–21 (2018).

Mann, J. P. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Semin. Liver Dis. 38, 1–13 (2018).

Baffy, G. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging menace. J. Hepatol. 56, 1384–1391 (2012).

Younes, R. & Bugianesi, E. Should we undertake surveillance for HCC in patients with NAFLD? J. Hepatol. 68, 326–334 (2018).

Estes, C. et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016–2030. J. Hepatol. S0168-8278, 32121–32124 (2018).

Amstrong, M. J. et al. Extrahepatic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 59, 1174–1197 (2014).

Tilg, H. & Mochen, A. R. Evolution of inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology 52, 1836–1846 (2010).

Friedman, S. L. et al. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 24, 908–922 (2018).

Schuppan, D. et al. Determinants of fibrosis progression and regression in NASH. J. Hepatol. 68, 238–250 (2018).

Ioannou, G. N. The role of cholesterol in the pathogenesis of NASH. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 84–95 (2016).

Lebeaupin, C. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 69, 927–947 (2018).

Neuschwander-Teri, B. A. Hepatic lipotoxicity and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: the central role of nontriglyceride fatty acid metabolites. Hepatology 52, 774–788 (2010).

Cannito, S. et al. Microvesicles released from fat-laden cells promote activation of hepatocellular NLRP3 inflammasome: a pro-inflammatory link between lipotoxicity and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. PLOS ONE 12, e0172575 (2017).

Bellanti, F. et al. Lipid oxidation products in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 111, 173–185 (2017).

Szabo, G. & Petrasek, J. Inflammasome activation and function in liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 387–400 (2015).

Weismann, D. & Binder, C. J. The innate immune response to products of phospholipid peroxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1818, 2465–2475 (2012).

Brandl, K. & Schnabl, B. Intestinal microbiota and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 33, 128–133 (2017).

Krenkel, O. & Tacke, F. Macrophages in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a role model of pathogenic immunometabolism. Semin. Liver Dis. 37, 189–197 (2017).

Tacke, F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 66, 1300–1312 (2017).

Friedman, S. L. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cenicriviroc for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with fibrosis. Hepatology 67, 1754–1767 (2018).

Locatelli, I. et al. Endogenous annexin A1 is a novel protective determinant in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 60, 531–544 (2014).

Cai, Y. et al. Disruption of adenosine 2A receptor exacerbates NAFLD through increasing inflammatory responses and SREBP1c activity. Hepatology 68, 48–61 (2018).

Yeh, M. M. & Brunt, E. M. Pathological features of fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 147, 754–764 (2014).

Gadd, V. L. et al. The portal inflammatory infiltrate and ductular reaction in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 59, 1393–1405 (2014).

Bruzzì, S. et al. B2-lymphocyte responses to oxidative stress-derived antigens contribute to the evolution of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Free Radic. Biol. Med. 124, 249–259 (2018).

Pitzalis, C. et al. Ectopic lymphoid-like structures in infection, cancer and autoimmunity. Nat Rev. Immunol. 14, 447–462 (2014).

Sutti, S. et al. Adaptive immune responses triggered by oxidative stress contribute to hepatic inflammation in NASH. Hepatology. 59, 886–897 (2014).

Wolf, M. J. et al. Metabolic activation of intrahepatic CD8+ T cells and NKT cells causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver cancer via cross-talk with hepatocytes. Cancer Cell 26, 549–564 (2014).

Herrero-Cervera A., et al. Genetic inactivation of the LIGHT (TNFSF14) cytokine in mice restores glucose homeostasis and diminishes hepatic steatosis. Diabetologia https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4962-6 (2019).

Weston, C. J. et al. Vascular adhesion protein-1 promotes liver inflammation and drives hepatic fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 501–520 (2015).

Grohmann, M. et al. Obesity drives STAT-1-dependent NASH and STAT-3-dependent HCC. Cell 175, 1289–1306.e20 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Dietary factors alter hepatic innate immune system in mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 42, 880–885 (2005).

Luo, X. Y. et al. IFN-γ deficiency attenuates hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a steatohepatitis model induced by a methionine- and choline-deficient high fat diet. Am. J. Physiol. Gastroinstest. Liver Physiol. 305, G891–G899 (2013).

Inzaugarat, M. E. et al. Altered phenotype and functionality of circulating immune cells characterize adult patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Clin. Immunol. 31, 1120–1130 (2011).

Ferreyra Solari, N. E. et al. The role of innate cells is coupled to a Th1-polarized immune response in pediatric nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Clin. Immunol. 32, 611–621 (2012).

Tang, Y. et al. Interleukin-17 exacerbates hepatic steatosis and inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 166, 281–290 (2011).

Molina M. F. et al. Type 3 cytokines in liver fibrosis and liver cancer. Cytokine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2018.07.028 (2018).

Rau, M. et al. Progression from nonalcoholic fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is marked by a higher frequency of Th17 cells in the liver and an increased Th17/resting regulatory T cell ratio in peripheral blood and in the liver. J. Immunol. 196, 97–105 (2016).

Harley, I. T. et al. IL-17 signaling accelerates the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology 59, 1830–1839 (2014).

Giles, D. A. et al. Regulation of inflammation by IL-17A and IL-17F modulates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease pathogenesis. PLOS ONE 11, e0149783 (2016).

Gomes, A. L. et al. Metabolic inflammation-associated IL-17A causes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 30, 161–175 (2016).

Rolla, S. et al. The balance between IL-17 and IL-22 produced by liver-infiltrating T-helper cells critically controls NASH development in mice. Clin. Sci. 130, 193–203 (2016).

Li, F. et al. The microbiota maintain homeostasis of liver-resident γδT-17 cells in a lipid antigen/CD1d-dependent manner. Nat. Commun. 7, 13839 (2017).

Ghazarian, M. et al. Type I interferon responses drive intrahepatic T cells to promote metabolic syndrome. Sci. Immunol. 2, eaai7616 (2017).

Bhattacharjee, J. et al. Hepatic natural killer T-cell and CD8+ T-cell signatures in mice with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol. Commun. 1, 299–310 (2017).

Novobrantseva, T. I. et al. Attenuated liver fibrosis in the absence of B cells. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 3072–3082 (2005).

Tsiantoulas, D. et al. Targeting B cells in atherosclerosis: closing the gap from bench to bedside. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 296–302 (2015).

Miyake, T. et al. B cell-activating factor is associated with the histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 7, 539–547 (2013).

Lund, F. E. Cytokine-producing B lymphocytes-key regulators of immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 332–338 (2008).

DiLillo, D. J. et al. B-lymphocyte effector functions in health and disease. Immunol. Res. 49, 281–292 (2011).

Béland, K. et al. Depletion of B cells induces remission of autoimmune hepatitis in mice through reduced antigen presentation and help to T cells. Hepatology 62, 1511–1523 (2015).

Thapa, M. et al. Liver fibrosis occurs through dysregulation of MyD88-dependent innate B-cell activity. Hepatology 61, 2067–2079 (2015).

McPherson, S. et al. Serum immunoglobulin levels predict fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 60, 1055–1062 (2014).

McLaughlin, T. et al. Role of innate and adaptive immunity in obesity-associated metabolic disease. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 5–13 (2017).

Busch, C. J. et al. Malondialdehyde epitopes are sterile mediators of hepatic inflammation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Hepatology 65, 1181–1195 (2017).

Papac-Milicevic, N. et al. Malondialdehyde epitopes as targets of immunity and the implications for atherosclerosis. Adv. Immunol. 131, 1–59 (2016).

Smallwood, M. J. et al. Oxidative stress in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 125, 3–14 (2018).

Rolla, R. et al. Detection of circulating antibodies against malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in patients with alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology 31, 878–884 (2000).

Albano, E. et al. Immune response toward lipid peroxidation products as a predictor of the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) to advanced fibrosis. Gut 54, 987–993 (2005).

Nobili, V. et al. Oxidative stress parameters in paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 26, 471–476 (2010).

Baumgardner, J. N. et al. N-acethylcysteine attenuates progression of liver pathology in a rat model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Nutr. 138, 1872–1879 (2008).

Bieghs, V. et al. Specific immunization strategies against oxidized low-density lipoprotein: a novel way to reduce nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 56, 894–903 (2012).

Gruber, S. et al. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin G promotes atherosclerosis and liver inflammation by suppressing the protective functions of B-1 cells. Cell Rep. 14, 2348–2361 (2016).

Hendrikx, T. et al. Low levels of IgM antibodies recognizing oxidation-specific epitopes are associated with human non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med. 14, 107 (2016).

Ketelhuth, D. F. & Hansson, G. K. Adaptive response of T and B cells in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 118, 668–678 (2016).

Harmon, D. B. et al. Protective role for B-1b B cells and IgM in obesity-associated inflammation, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 36, 682–691 (2016).

Tosello-Trampont, A. et al. Immunoregulatory role of NK cells in tissue inflammation and regeneration. Front. Immunol. 8, 301 (2017).

Marrero, I. et al. Complex network of NKT cell subsets controls immune homeostasis in liver and gut. Front. Immunol. 9, 2082 (2018).

Kremer, M. et al. Kupffer cell and interleukin-12-dependent loss of natural killer T cells in hepatosteatosis. Hepatology 51, 130–141 (2010).

Tang, Z. H. et al. Tim-3/galectin-9 regulate the homeostasis of hepatic NKT cells in a murine model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Immunol. 190, 1788–1796 (2013).

Tajiri, K. et al. Role of liver-infiltrating CD3+CD56+ natural killer T cells in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 673–680 (2009).

Syn, W. K. et al. NKT-associated hedgehog and osteopontin drive fibrogenesis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 61, 1323–1329 (2012).

Maricic, I. et al. Differential activation of hepatic invariant NKT cell subsets plays a key role in progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Immunol. 201, 3017–3035 (2018).

Wehr, A. et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR6-dependent hepatic NK T cell accumulation promotes inflammation and liver fibrosis. J. Immunol. 190, 5226–5236 (2013).

Locatelli, I. et al. NF-kB1 deficiency stimulates the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in mice by promoting NKT-mediated responses. Clin. Sci. 124, 279–287 (2013).

Gordy, L. E. et al. IL-15 regulates homeostasis and terminal maturation of NKT cells. J. Immunol. 187, 6335–6345 (2011).

Cepero-Donates, Y. et al. Interleukin-15-mediated inflammation promotes non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cytokine 82, 102–111 (2016).

Crispe, I. N. Immune tolerance in liver disease. Hepatology 60, 2109–2117 (2014).

Horst, A. K. et al. Modulation of liver tolerance by conventional and nonconventional antigen-presenting cells and regulatory immune cells. Cell Mol. Immunol. 13, 277–292 (2016).

Rahman, A. H. & Aloman, C. Dendritic cells and liver fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1832, 998–1004 (2013).

Eckert Ch et al. The complex myeloid network of the liver with diverse functional capacity at steady state and in inflammation. Front. Immunol. 6, 179 (2016).

Doherty, D. G. Antigen-presenting cell function in the tolerogenic liver environment. J. Autoimmun. 66, 60–75 (2016).

Heymann, F. & Take, F. Immunology of the liver — from homeostasis to disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenteol. Hepatol. 13, 88–110 (2016).

Ibrahim, J. et al. Dendritic cell populations with different concentrations of lipid regulate tolerance and immunity in mouse and human liver. Gastroenterology 143, 1061–1072 (2012).

Tsung, A. et al. Increasing numbers of hepatic dendritic cells promote HMGB1-mediated ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81, 119–128 (2007).

Heier, E. C. et al. Murine CD103+ dendritic cells protect against steatosis progression towards steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 66, 1241–1250 (2017).

Sutti, S. et al. CX3CR1-expressing inflammatory dendritic cells contribute to the progression of steatohepatitis. Clin. Sci. 129, 797–808 (2015).

Segura, E. & Amigorena, S. Inflammatory dendritic cells in mice and humans. Trends Immunol. 34, 440–445 (2013).

Henning, J. R. et al. Dendritic cells limit fibroinflammatory injury in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 58, 589–602 (2013).

Tosello-Trampont, A. C. et al. NKp46+ natural killer cells attenuate metabolism-induced hepatic fibrosis by regulating macrophage activation in mice. Hepatology 63, 799–812 (2016).

Ley, K. et al. How costimulatory and coinhibitory pathways shape atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37, 764–777 (2017).

Seijkens, T. et al. Immune cell crosstalk in obesity: a key role for costimulation? Diabetes 63, 3982–3991 (2014).

Sun, G. et al. OX40 regulates both innate and adaptive immunity and promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Rep. 25, 3786–3799 (2018).

Willoughby, J. et al. OX40: structure and function — what questions remain? Mol. Immunol. 83, 13–22 (2017).

Liu, B. et al. OX40 promotes obesity-induced adipose inflammation and insulin resistance. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 74, 3827–3840 (2017).

Vilar-Gomez, E. & Chalasani, N. Non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: clinical prediction rules and blood-based biomarkers. J. Hepatol. 68, 305–315 (2018).

Ma, X. et al. A high-fat diet and regulatory T cells influence susceptibility to endotoxin-induced liver injury. Hepatology 46, 1519–1529 (2007).

Griesenauer, B. & Paczesny, S. The ST2/IL-33 axis in immune cells during inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 8, 475 (2017).

Francisco, V. et al. Obesity, fat mass and immune system: role for leptin. Front. Physiol. 9, 640 (2018).

Chatzigeorgiou, A. et al. Dual role of B7 costimulation in obesity-related nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and metabolic dysregulation. Hepatology 60, 1196–1210 (2014).

Heymann, F. et al. Liver inflammation abrogates immunological tolerance induced by Kupffer cells. Hepatology 62, 279–291 (2015).

Bashiardes, S. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver and the gut microbiota. Mol. Metab. 5, 782–794 (2016).

Henao-Mejia, J. et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature 482, 179–185 (2012).

Schneider, K. M. et al. CX3CR1 is a gatekeeper for intestinal barrier integrity in mice: limiting steatohepatitis by maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Hepatology 62, 1405–1416 (2015).

Li, B. et al. The microbiome and autoimmunity: a paradigm from the gut-liver axis. Cell Mol Immunol. 15, 595–609 (2018).

Rau, M. et al. Fecal SCFAs and SCFA-producing bacteria in gut microbiome of human NAFLD as a putative link to systemic T-cell activation and advanced disease. United European Gastroenterol. J. 6, 1496–1507 (2018).

Ringelhan, M. et al. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Immunol. 19, 222–232 (2018).

Park, E. J. et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell 140, 197–208 (2010).

De Minicis, S. et al. HCC development is associated to peripheral insulin resistance in a mouse model of NASH. PLOS ONE 9, e97136 (2014).

Nakagawa, H. et al. ER stress cooperates with hypernutrition to trigger TNF-dependent spontaneous HCC development. Cancer Cell 26, 331–343 (2014).

Ma, C. et al. NAFLD causes selective CD4+ T lymphocyte loss and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature 531, 253–257 (2016).

Shalapour, S. et al. Inflammation-induced IgA+ cells dismantle anti-liver cancer immunity. Nature 551, 340–345 (2017).

Rotman, Y. & Sanyal, A. J. Current and upcoming pharmacotherapy for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 66, 180–190 (2017).

Salmi, M. & Jalkanen, S. Vascular adhesion protein-1: a cell surface amine oxidase in translation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 30, 314–332 (2019).

Samy, E. et al. Targeting BAFF and APRIL in systemic lupus erythematosus and other antibody-associated diseases. Int. Rev. Immunol. 36, 3–19 (2017).

Weiner, H. L. et al. Oral tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 241, 241–259 (2011).

Foks, A. C. et al. Treating atherosclerosis with regulatory T cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 280–287 (2015).

Ilan, Y. et al. Induction of regulatory T cells decreases adipose inflammation and alleviates insulin resistance in ob/ob mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9765–9770 (2010).

Ilan, Y. et al. Immunotherapy with oral administration of humanized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody: a novel gut-immune system-based therapy for metaflammation and NASH. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 193, 275–283 (2018).

Adar, T. et al. Oral administration of immunoglobulin G-enhanced colostrum alleviates insulin resistance and liver injury and is associated with alterations in natural killer T cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 167, 252–260 (2012).

Mizrahi, M. et al. Alleviation of insulin resistance and liver damage by oral administration of Imm124-E is mediated by increased Tregs and associated with increased serum GLP-1 and adiponectin: results of a phase I/II clinical trial in NASH. J. Inflamm. Res. 5, 141–150 (2012).

Wawrzyniak, M. et al. Role of regulatory cells in oral tolerance. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 9, 107–115 (2017).

Elinav, E. et al. Amelioration of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and glucose intolerance in ob/ob mice by oral immune regulation towards liver-extracted proteins is associated with elevated intrahepatic NKT lymphocytes and serum IL-10 levels. J. Pathol. 208, 74–81 (2006).

Su, L. et al. Mesenteric lymph node CD4+ T lymphocytes migrate to liver and contribute to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Immunol. 337, 33–41 (2019).

Wu, Z. et al. Mesenteric adipose tissue B lymphocytes promote local and hepatic inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. J. Cell Mol. Med. 23, 3375–3385 (2019).

Wang, X. & Tian, Z. Gamma delta T cells in liver diseases. Front. Med. 2, 262–268 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Type 3 innate lymphoid cell: a new player in liver fibrosis progression. Clin. Sci. 132, 2565–2582 (2018).

Luci, C. et al. Natural killer cells and type 1 innate lymphoid cells are new actors in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Immunol. 28, 10–1192 (2019).

Hegde, P. et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells are a profibrogenic immune cell population in the liver. Nat. Commun. 9, 2146 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells improve nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through regulating macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol. 9, 1994 (2018).

Francque, S. M. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: pathophysiological mechanisms and implications. J. Hepatol. 65, 425–443 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The work of the authors is supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Education (MIUR), Regional Government of Piedmont, Università del Piemonte Orientale (FAR 2015) and Fondazione Cariplo Milan, Italy (Grants 2011/0470 and 2017/0535).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to all aspects of the preparation of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology thanks Andreas Geier, Matteo Iannacone and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sutti, S., Albano, E. Adaptive immunity: an emerging player in the progression of NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 17, 81–92 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-019-0210-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-019-0210-2

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptomics-driven metabolic pathway analysis reveals similar alterations in lipid metabolism in mouse MASH model and human

Communications Medicine (2024)

-

Emerging Drug Therapies for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Glimpse into the Horizon

Current Hepatology Reports (2024)

-

Prevalence of Steatotic Liver Disease Among US Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2024)

-

Identification and immunological characterization of lipid metabolism-related molecular clusters in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Lipids in Health and Disease (2023)

-

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma: pathogenesis and treatment

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2023)