Abstract

In the 1990s, selenium was identified as a component of an enzyme that activates thyroid hormone; since this discovery, the relevance of selenium to thyroid health has been widely studied. Selenium, known primarily for the antioxidant properties of selenoenzymes, is obtained mainly from meat, seafood and grains. Intake levels vary across the world owing largely to differences in soil content and factors affecting its bioavailability to plants. Adverse health effects have been observed at both extremes of intake, with a narrow optimum range. Epidemiological studies have linked an increased risk of autoimmune thyroiditis, Graves disease and goitre to low selenium status. Trials of selenium supplementation in patients with chronic autoimmune thyroiditis have generally resulted in reduced thyroid autoantibody titre without apparent improvements in the clinical course of the disease. In Graves disease, selenium supplementation might lead to faster remission of hyperthyroidism and improved quality of life and eye involvement in patients with mild thyroid eye disease. Despite recommendations only extending to patients with Graves ophthalmopathy, selenium supplementation is widely used by clinicians for other thyroid phenotypes. Ongoing and future trials might help identify individuals who can benefit from selenium supplementation, based, for instance, on individual selenium status or genetic profile.

Key points

-

Epidemiological data have suggested increased prevalence of benign thyroid disease with low selenium status, but the optimum range of intake is likely to be narrow, warranting a cautious approach to recommending selenium supplementation.

-

The effects of selenium supplementation might be mediated via repletion of antioxidant or immune-modulating selenoproteins, and polymorphisms in genes that encode selenoproteins might determine susceptibility to supplementation.

-

In chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, selenium supplementation reduces circulating levels of thyroid autoantibodies; however, evaluation of clinically important primary outcomes has not shown improvement and should be prioritized in future trials.

-

Observational studies have indicated that low selenium status is an iodine-independent risk factor for goitre; however, this finding has not been followed up by intervention trials in humans.

-

In Graves disease, selenium supplementation might facilitate biochemical restoration of euthyroidism and reduce ocular involvement, but these results need to be confirmed.

-

Treatment with selenium supplementation is widely used by clinicians across the spectrum of autoimmune thyroid diseases, despite the fact that it is recommended only in the treatment of mild Graves orbitopathy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schwarz, K. & Foltz, C. M. Selenium as an integral part of factor 3 against dietary necrotic liver degeneration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79, 3292–3293 (1957).

Hatfield, D. L. & Gladyshev, V. N. How selenium has altered our understanding of the genetic code. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 3565–3576 (2002).

Rayman, M. P. Selenium and human health. Lancet 379, 1256–1268 (2012). This article presents an overview of the different roles of selenium in relation to human health.

Clark, L. C. et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial. Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. JAMA 276, 1957–1963 (1996).

Lippman, S. M. et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 301, 39–51 (2009).

Fan, Y. et al. Selenium supplementation for autoimmune thyroiditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 904573 (2014).

Wichman, J., Winther, K. H., Bonnema, S. J. & Hegedus, L. Selenium supplementation significantly reduces thyroid autoantibody levels in patients with chronic autoimmune thyroiditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid 26, 1681–1692 (2016). This article is a systematic review of selenium supplementation trials in AIT.

Kohrle, J., Jakob, F., Contempre, B. & Dumont, J. E. Selenium, the thyroid, and the endocrine system. Endocr. Rev. 26, 944–984 (2005). This article is a comprehensive review of the roles of different selenoproteins in the endocrine system, including the thyroid.

Labunskyy, V. M., Hatfield, D. L. & Gladyshev, V. N. Selenoproteins: molecular pathways and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 94, 739–777 (2014).

Schweizer, U. & Fradejas-Villar, N. Why 21? The significance of selenoproteins for human health revealed by inborn errors of metabolism. FASEB J. 30, 3669–3681 (2016).

Dumitrescu, A. M. & Refetoff, S. Inherited defects of thyroid hormone metabolism. Ann. Endocrinol. 72, 95–98 (2011).

Schmutzler, C. et al. Selenoproteins of the thyroid gland: expression, localization and possible function of glutathione peroxidase 3. Biol. Chem. 388, 1053–1059 (2007).

Schomburg, L. Selenium, selenoproteins and the thyroid gland: interactions in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 8, 160–171 (2012).

Panicker, V. et al. Common variation in the DIO2 gene predicts baseline psychological well-being and response to combination thyroxine plus triiodothyronine therapy in hypothyroid patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 1623–1629 (2009).

Jo, S. et al. Type 2 deiodinase polymorphism causes ER stress and hypothyroidism in the brain. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 230–245 (2019).

Carlé, A., Faber, J., Steffensen, R., Laurberg, P. & Nygaard, B. Hypothyroid patients encoding combined MCT10 and DIO2 gene polymorphisms may prefer L-T3 + L-T4 combination treatment - data using a blind, randomized, clinical study. Eur. Thyroid J. 6, 143–151 (2017).

Schomburg, L. & Köhrle, J. On the importance of selenium and iodine metabolism for thyroid hormone biosynthesis and human health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 52, 1235–1246 (2008).

Lin, J. C. et al. Glutathione peroxidase 3 gene polymorphisms and risk of differentiated thyroid cancer. Surgery 145, 508–513 (2009).

Curran, J. E. et al. Genetic variation in selenoprotein S influences inflammatory response. Nat. Genet. 37, 1234–1241 (2005).

Santos, L. R. et al. A polymorphism in the promoter region of the selenoprotein S gene (SEPS1) contributes to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis susceptibility. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, E719–E723 (2014). This case–control study shows increased risk of AIT with a polymorphism in the SELENOS gene. The polymorphism further increased the risk in males, suggesting sexual dimorphism.

Johnson, C. C., Fordyce, F. M. & Rayman, M. P. Symposium on ‘Geographical and geological influences on nutrition’: factors controlling the distribution of selenium in the environment and their impact on health and nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 69, 119–132 (2010).

Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids (National Academies Press, 2000).

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for selenium. EFSA J. 12, 3846 (2014).

Rayman, M. P. Food-chain selenium and human health: emphasis on intake. Br. J. Nutr. 100, 254–268 (2008).

Rayman, M. P. The use of high-selenium yeast to raise selenium status: how does it measure up? Br. J. Nutr. 92, 557–573 (2004).

Achouba, A., Dumas, P., Ouellet, N., Lemire, M. & Ayotte, P. Plasma levels of selenium-containing proteins in Inuit adults from Nunavik. Environ. Int. 96, 8–15 (2016).

Swanson, C. A. et al. Human [74Se]selenomethionine metabolism: a kinetic model. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54, 917–926 (1991).

Rayman, M. P. et al. Effect of long-term selenium supplementation on mortality: results from a multiple-dose, randomised controlled trial. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 127, 46–54 (2018). This was a randomized, controlled trial that questioned the safety of current selenium upper tolerable intake limits.

Whanger, P. D. Selenocompounds in plants and animals and their biological significance. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 21, 223–232 (2002).

Rayman, M. P., Infante, H. G. & Sargent, M. Food-chain selenium and human health: spotlight on speciation. Br. J. Nutr. 100, 238–253 (2008).

Patterson, B. H. et al. Human selenite metabolism: a kinetic model. Am. J. Physiol. 257, R556–R567 (1989).

Fairweather-Tait, S. J., Collings, R. & Hurst, R. Selenium bioavailability: current knowledge and future research requirements. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 1484s–1491s (2010).

Francesconi, K. A. & Pannier, F. Selenium metabolites in urine: a critical overview of past work and current status. Clin. Chem. 50, 2240–2253 (2004).

Robinson, J. R., Robinson, M. F., Levander, O. A. & Thomson, C. D. Urinary excretion of selenium by New Zealand and North American human subjects on differing intakes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 41, 1023–1031 (1985).

Ashton, K. et al. Methods of assessment of selenium status in humans: a systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 2025S–2039S (2009).

Rayman, M. P. et al. Effect of selenium on markers of risk of pre-eclampsia in UK pregnant women: a randomised, controlled pilot trial. Br. J. Nutr. 112, 99–111 (2014).

Rayman, M. P., Bode, P. & Redman, C. W. Low selenium status is associated with the occurrence of the pregnancy disease preeclampsia in women from the United Kingdom. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 189, 1343–1349 (2003).

Duncan, A., Talwar, D., McMillan, D. C., Stefanowicz, F. & O’Reilly, D. S. Quantitative data on the magnitude of the systemic inflammatory response and its effect on micronutrient status based on plasma measurements. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95, 64–71 (2012).

Stefanowicz, F. A. et al. Erythrocyte selenium concentration as a marker of selenium status. Clin. Nutr. 32, 837–842 (2013).

European Accreditation–Eurolab–Eurochem Reference Materials Working Group. Accreditation EA-4/14 INF: The Selection and Use of Reference Materials https://european-accreditation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ea-4-14-inf-rev00-february-2003-rev.pdf (Eurachem, 2003).

Mita, Y. et al. Selenoprotein P-neutralizing antibodies improve insulin secretion and glucose sensitivity in type 2 diabetes mouse models. Nat. Commun. 8, 1658 (2017).

Xia, Y., Hill, K. E., Byrne, D. W., Xu, J. & Burk, R. F. Effectiveness of selenium supplements in a low-selenium area of China. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 829–834 (2005).

Yang, G. Q. & Xia, Y. M. Studies on human dietary requirements and safe range of dietary intakes of selenium in China and their application in the prevention of related endemic diseases. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 8, 187–201 (1995).

Hughes, D. J. et al. Selenium status is associated with colorectal cancer risk in the European prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition cohort. Int. J. Cancer 136, 1149–1161 (2015).

Laclaustra, M., Navas-Acien, A., Stranges, S., Ordovas, J. M. & Guallar, E. Serum selenium concentrations and diabetes in U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 1409–1413 (2009).

Burek, C. L. & Rose, N. R. Autoimmune thyroiditis and ROS. Autoimmun. Rev. 7, 530–537 (2008).

Smith, T. J. & Hegedus, L. Graves’ disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1552–1565 (2016). This comprehensive review on Graves disease includes updates on disease aetiology and pathogenesis.

Marino, M., Dottore, G. R., Leo, M. & Marcocci, C. Mechanistic pathways of selenium in the treatment of Graves’ disease and Graves’ orbitopathy. Horm. Metab. Res. 50, 887–893 (2018).

Rotondo Dottore, G. et al. Antioxidant actions of selenium in orbital fibroblasts: a basis for the effects of selenium in Graves’ orbitopathy. Thyroid 27, 271–278 (2017).

Nettore, I. C. et al. Selenium supplementation modulates apoptotic processes in thyroid follicular cells. Biofactors 43, 415–423 (2017).

Balázs, C. & Kaczur, V. Effect of selenium on HLA-DR expression of thyrocytes. Autoimmune Dis. 2012, 374635 (2012).

Huang, Z., Rose, A. H. & Hoffmann, P. R. The role of selenium in inflammation and immunity: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 705–743 (2012).

Avery, J. C. & Hoffmann, P. R. Selenium, selenoproteins, and immunity. Nutrients 10, 1203 (2018). A comprehensive review on the roles of selenoproteins in the immune system.

Wang, W. et al. Effects of selenium supplementation on spontaneous autoimmune thyroiditis in NOD.H-2h4 mice. Thyroid 25, 1137–1144 (2015).

Xue, H. et al. Selenium upregulates CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in iodine-induced autoimmune thyroiditis model of NOD.H-2h4 mice. Endocr. J. 57, 595–601 (2010).

McLachlan, S. M., Aliesky, H., Banuelos, B., Hee, S. S. Q. & Rapoport, B. Variable effects of dietary selenium in mice that spontaneously develop a spectrum of thyroid autoantibodies. Endocrinology 158, 3754–3764 (2017). This experimental study provided evidence that is consistent with increased risk of AIT with low selenium status.

Contempre, B. et al. Effect of selenium supplementation in hypothyroid subjects of an iodine and selenium deficient area: the possible danger of indiscriminate supplementation of iodine-deficient subjects with selenium. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 73, 213–215 (1991).

Contempre, B. et al. Effect of selenium supplementation on thyroid hormone metabolism in an iodine and selenium deficient population. Clin. Endocrinol. 36, 579–583 (1992).

Winther, K. H. et al. Does selenium supplementation affect thyroid function? Results from a randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial in a Danish population. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 172, 657–667 (2015).

Duffield, A. J., Thomson, C. D., Hill, K. E. & Williams, S. An estimation of selenium requirements for New Zealanders. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 70, 896–903 (1999).

Thomson, C. D., McLachlan, S. K., Grant, A. M., Paterson, E. & Lillico, A. J. The effect of selenium on thyroid status in a population with marginal selenium and iodine status. Br. J. Nutr. 94, 962–968 (2005).

Rayman, M. P. et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of selenium supplementation on thyroid function in the elderly in the United Kingdom. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 370–378 (2008).

Hansen, P. S. et al. Genetic and environmental causes of individual differences in thyroid size: a study of healthy Danish twins. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89, 2071–2077 (2004).

Derumeaux, H. et al. Association of selenium with thyroid volume and echostructure in 35- to 60-year-old French adults. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 148, 309–315 (2003).

Rasmussen, L. B. et al. Selenium status, thyroid volume, and multiple nodule formation in an area with mild iodine deficiency. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 164, 585–590 (2011).

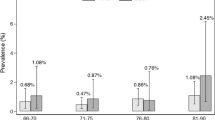

Wu, Q. et al. Low population selenium status is associated with increased prevalence of thyroid disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 4037–4047 (2015). This was a large, community-based study that confirms previously reported associations about increased risk of thyroid disease with low selenium status.

Ajjan, R. A. & Weetman, A. P. The pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: further developments in our understanding. Horm. Metab. Res. 47, 702–710 (2015). A review on AIT pathogenesis, which discusses the importance of selenium.

Brix, T. H., Kyvik, K. O. & Hegedus, L. A population-based study of chronic autoimmune hypothyroidism in Danish twins. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85, 536–539 (2000).

Hansen, P. S., Brix, T. H., Iachine, I., Kyvik, K. O. & Hegedus, L. The relative importance of genetic and environmental effects for the early stages of thyroid autoimmunity: a study of healthy Danish twins. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 154, 29–38 (2006).

Brix, T. H. & Hegedus, L. Twin studies as a model for exploring the aetiology of autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin. Endocrinol. 76, 457–464 (2012).

Bulow Pedersen, I. et al. Serum selenium is low in newly diagnosed Graves’ disease: a population-based study. Clin. Endocrinol. 79, 584–590 (2013).

Gärtner, R., Gasnier, B. C., Dietrich, J. W., Krebs, B. & Angstwurm, M. W. Selenium supplementation in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis decreases thyroid peroxidase antibodies concentrations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 1687–1691 (2002).

Gärtner, R. & Gasnier, B. C. Selenium in the treatment of autoimmune thyroiditis. Biofactors 19, 165–170 (2003).

Duntas, L. H., Mantzou, E. & Koutras, D. A. Effects of a six month treatment with selenomethionine in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 148, 389–393 (2003).

Turker, O., Kumanlioglu, K., Karapolat, I. & Dogan, I. Selenium treatment in autoimmune thyroiditis: 9-month follow-up with variable doses. J. Endocrinol. 190, 151–156 (2006).

Mazokopakis, E. E. et al. Effects of 12 months treatment with L-selenomethionine on serum anti-TPO levels in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid 17, 609–612 (2007).

Balázs, C. The effect of selenium therapy on autoimmune thyroiditis. Orv. Hetil. 149, 1227–1232 (2008).

Karanikas, G. et al. No immunological benefit of selenium in consecutive patients with autoimmune thyroiditis. Thyroid 18, 7–12 (2008).

Kvicala, J. et al. Effect of selenium supplementation on thyroid antibodies. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 280, 275–279 (2009).

Nacamulli, D. et al. Influence of physiological dietary selenium supplementation on the natural course of autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin. Endocrinol. 73, 535–539 (2010).

Krysiak, R. & Okopien, B. The effect of levothyroxine and selenomethionine on lymphocyte and monocyte cytokine release in women with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 2206–2215 (2011).

Krysiak, R. & Okopien, B. Haemostatic effects of levothyroxine and selenomethionine in euthyroid patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thromb. Haemost. 108, 973–980 (2012).

Bhuyan, A. K., Sarma, D. & Saikia, U. K. Selenium and the thyroid: a close-knit connection. Indian. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 16, S354–S355 (2012).

Anastasilakis, A. D. et al. Selenomethionine treatment in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis: a prospective, quasi-randomised trial. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 66, 378–383 (2012).

Eskes, S. A. et al. Selenite supplementation in euthyroid subjects with thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Clin. Endocrinol. 80, 444–451 (2014).

de Farias, C. R. et al. A randomized-controlled, double-blind study of the impact of selenium supplementation on thyroid autoimmunity and inflammation with focus on the GPx1 genotypes. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 38, 1065–1074 (2015).

Pilli, T. et al. IFNγ-inducible chemokines decrease upon selenomethionine supplementation in women with euthyroid autoimmune thyroiditis: comparison between two doses of selenomethionine (80 or 160 mug) versus placebo. Eur. Thyroid J. 4, 226–233 (2015).

Pirola, I., Gandossi, E., Agosti, B., Delbarba, A. & Cappelli, C. Selenium supplementation could restore euthyroidism in subclinical hypothyroid patients with autoimmune thyroiditis. Endokrynol. Pol. 67, 567–571 (2016).

Esposito, D. et al. Influence of short-term selenium supplementation on the natural course of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: clinical results of a blinded placebo-controlled randomized prospective trial. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 40, 83–89 (2017).

Yu, L. et al. Levothyroxine monotherapy versus levothyroxine and selenium combination therapy in chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 40, 1243–1250 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Decreased thyroid peroxidase antibody titer in response to selenium supplementation in autoimmune thyroiditis and the influence of a SEPP gene polymorphism: a prospective, multicenter study in China. Thyroid 28, 1674–1681 (2018).

van Zuuren, E. J., Albusta, A. Y., Fedorowicz, Z., Carter, B. & Pijl, H. Selenium supplementation for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Eur. Thyroid J. 3, 25–31 (2014).

Toulis, K. A., Anastasilakis, A. D., Tzellos, T. G., Goulis, D. G. & Kouvelas, D. Selenium supplementation in the treatment of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thyroid 20, 1163–1173 (2010).

Winther, K. H., Wichman, J. E., Bonnema, S. J. & Hegedus, L. Insufficient documentation for clinical efficacy of selenium supplementation in chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, based on a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 55, 376–385 (2017).

Stagnaro-Green, A. Approach to the patient with postpartum thyroiditis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 334–342 (2012).

Negro, R. et al. The influence of selenium supplementation on postpartum thyroid status in pregnant women with thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 1263–1268 (2007).

Mao, J. et al. Effect of low-dose selenium on thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid function in UK pregnant women with mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency. Eur. J. Nutr. 55, 55–61 (2016).

Mantovani, G. et al. Selenium supplementation in the management of thyroid autoimmunity during pregnancy: results of the “SERENA study”, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Endocrine 66, 542–550 (2019).

Brix, T. H., Kyvik, K. O., Christensen, K. & Hegedus, L. Evidence for a major role of heredity in Graves’ disease: a population-based study of two Danish twin cohorts. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 930–934 (2001).

Wertenbruch, T. et al. Serum selenium levels in patients with remission and relapse of Graves’ disease. Med. Chem. 3, 281–284 (2007).

Arikan, T. A. Plasma selenium levels in first trimester pregnant women with hyperthyroidism and the relationship with thyroid hormone status. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 167, 194–199 (2015).

Khong, J. J. et al. Serum selenium status in Graves’ disease with and without orbitopathy: a case-control study. Clin. Endocrinol. 80, 905–910 (2014).

Dehina, N., Hofmann, P. J., Behrends, T., Eckstein, A. & Schomburg, L. Lack of association between selenium status and disease severity and activity in patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Eur. Thyroid J. 5, 57–64 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Role of selenium intake for risk and development of hyperthyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104, 568–580 (2019).

Effraimidis, G. & Wiersinga, W. M. Mechanisms in endocrinology: autoimmune thyroid disease: old and new players. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 170, R241–R252 (2014).

Calissendorff, J., Mikulski, E., Larsen, E. H. & Moller, M. A prospective investigation of Graves’ disease and selenium: thyroid hormones, auto-antibodies and self-rated symptoms. Eur. Thyroid J. 4, 93–98 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Effect of selenium supplementation on recurrent hyperthyroidism caused by Graves’ disease: a prospective pilot study. Horm. Metab. Res. 48, 559–564 (2016).

Leo, M. et al. Effects of selenium on short-term control of hyperthyroidism due to Graves’ disease treated with methimazole: results of a randomized clinical trial. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 40, 281–287 (2017).

Kahaly, G. J., Riedl, M., Konig, J., Diana, T. & Schomburg, L. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of selenium in Graves hyperthyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102, 4333–4341 (2017).

Zheng, H. et al. Effects of selenium supplementation on Graves’ disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 3763565 (2018). A meta-analysis of trials of selenium supplementation in Graves disease.

Marcocci, C. et al. Selenium and the course of mild Graves’ orbitopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1920–1931 (2011). The only study that has investigated the effects of selenium supplementation in Graves ophthalmopathy and led to introduction of selenium supplementation in Graves ophthalmopathy.

Negro, R. et al. A 2016 Italian survey about the clinical use of selenium in thyroid disease. Eur. Thyroid J. 5, 164–170 (2016).

Winther, K. H., Papini, E., Attanasio, R., Negro, R. & Hegedüs, L. A 2018 European Thyroid Association survey on the use of selenium supplementation in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Eur. Thyroid J. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504781 (2019).

Negro, R., Hegedus, L., Attanasio, R., Papini, E. & Winther, K. H. A 2018 European Thyroid Association survey on the use of selenium supplementation in Graves’ hyperthyroidism and Graves’ orbitopathy. Eur. Thyroid J. 8, 7–15 (2019).

Pearce, S. H. et al. 2013 ETA guideline: management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur. Thyroid J. 2, 215–228 (2013).

Jonklaas, J. et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Thyroid 24, 1670–1751 (2014).

Lazarus, J. et al. 2014 European Thyroid Association guidelines for the management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy and in children. Eur. Thyroid J. 3, 76–94 (2014).

Alexander, E. K. et al. 2017 guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid 27, 315–389 (2017).

Kahaly, G. J. et al. 2018 European Thyroid Association guideline for the management of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Eur. Thyroid J. 7, 167–186 (2018).

Ross, D. S. et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association guidelines for diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 26, 1343–1421 (2016).

Bartalena, L. et al. The 2016 European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy guidelines for the management of Graves’ orbitopathy. Eur. Thyroid J. 5, 9–26 (2016).

O’Toole, D., Raisbeck, M., Case, J. C. & Whitson, T. D. Selenium-induced “blind staggers” and related myths. A commentary on the extent of historical livestock losses attributed to selenosis on western US rangelands. Vet. Pathol. 33, 104–116 (1996).

Yang, G. Q., Wang, S. Z., Zhou, R. H. & Sun, S. Z. Endemic selenium intoxication of humans in China. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 37, 872–881 (1983).

Yang, G. & Zhou, R. Further observations on the human maximum safe dietary selenium intake in a seleniferous area of China. J. Trace Elem. Electrolytes Health Dis. 8, 159–165 (1994).

Kristal, A. R. et al. Baseline selenium status and effects of selenium and vitamin E supplementation on prostate cancer risk. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 106, djt456 (2014).

Stranges, S. et al. Effects of long-term selenium supplementation on the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 147, 217–223 (2007).

Duffield-Lillico, A. J. et al. Selenium supplementation and secondary prevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer in a randomized trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 95, 1477–1481 (2003).

Kim, J. et al. Association between serum selenium level and the presence of diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Metab. J. 43, 447–460 (2019).

Kohler, L. N. et al. Selenium and type 2 diabetes: systematic review. Nutrients 10, E1924 (2018).

Jacobs, E. T. et al. Selenium supplementation and insulin resistance in a randomized, clinical trial. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care 7, e000613 (2019).

Stranges, S. et al. Effect of selenium supplementation on changes in HbA1c: results from a multiple-dose, randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 21, 541–549 (2019).

Steinbrenner, H., Speckmann, B., Pinto, A. & Sies, H. High selenium intake and increased diabetes risk: experimental evidence for interplay between selenium and carbohydrate metabolism. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 48, 40–45 (2011).

Speckmann, B. et al. Selenoprotein P expression is controlled through interaction of the coactivator PGC-1α with FoxO1a and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α transcription factors. Hepatology 48, 1998–2006 (2008).

Misu, H. et al. A liver-derived secretory protein, selenoprotein P, causes insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 12, 483–495 (2010).

Hellwege, J. N. et al. Genetic variants in selenoprotein P plasma 1 gene (SEPP1) are associated with fasting insulin and first phase insulin response in Hispanics. Gene 534, 33–39 (2014).

Zhang, Q. et al. Selenium levels in community dwellers with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 191, 354–362 (2019).

Scientific Committee on Food & Scientific Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. Tolerable upper intake levels for vitamins and minerals. (European Food Safety Authority, 2006).

Kipp, A. P. et al. Revised reference values for selenium intake. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 32, 195–199 (2015).

Hurst, R. et al. Establishing optimal selenium status: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 923–931 (2010).

Winther, K. H., Bonnema, S. J. & Hegedus, L. Is selenium supplementation in autoimmune thyroid diseases justified? Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 24, 348–355 (2017).

Winther, K. H. et al. The chronic autoimmune thyroiditis quality of life selenium trial (CATALYST): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 15, 115 (2014).

Watt, T. et al. The thyroid-related quality of life measure ThyPRO has good responsiveness and ability to detect relevant treatment effects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 3708–3717 (2014).

Watt, T. et al. Development of a short version of the Thyroid-Related Patient-Reported Outcome ThyPRO. Thyroid 25, 1069–1079 (2015).

Winther, K. H. et al. Disease-specific as well as generic quality of life is widely impacted in autoimmune hypothyroidism and improves during the first six months of levothyroxine therapy. PLoS One 11, e0156925 (2016).

Watt, T. et al. Selenium supplementation for patients with Graves’ hyperthyroidism (the GRASS trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 14, 119 (2013).

Seale, L. A., Ogawa-Wong, A. N. & Berry, M. J. Sexual dimorphism in selenium metabolism and selenoproteins. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 127, 198–205 (2018). A review highlighting the importance of considering sex differences in selenium metabolism and selenoprotein action when analysing laboratory and clinical data.

Hybsier, S. et al. Sex-specific and inter-individual differences in biomarkers of selenium status identified by a calibrated ELISA for selenoprotein P. Redox Biol. 11, 403–414 (2017).

Prasad, V., Gall, V. & Cifu, A. The frequency of medical reversal. Arch. Intern. Med. 171, 1675–1676 (2011).

Rayman M. P. & Duntas L. H. in The Thyroid and Its Diseases: A Comprehensive Guide for the Clinician (eds Luster, M., Duntas, L. H. & Wartofsky, L.) 109–126 (Springer International, 2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the long-term collaboration within the ThyQoL group (T. Watt, Å.K. Rasmussen, P. Cramon, J. Bjørner, M. Grønvold, F. Pociot, U. Feldt-Rasmussen), which at present, among a number of efforts, is investigating the potential benefit of selenium supplementation in Graves disease and chronic autoimmune thyroiditis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors researched data for the article, made substantial contributions to the discussion of content and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission. K.H.W., M.P.R. and L.H. wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Glossary

- Selenoproteins

-

Proteins that include a selenocysteine residue in their amino acid sequence.

- Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis

-

Patients with thyroid autoantibodies with or without goitre and with or without hypothyroidism.

- Selenium speciation

-

The chemical form or compound in which selenium occurs in food, in the environment or in the body.

- Neutron activation analysis

-

An analytical method that uses a neutron beam to determine the concentrations of elements in a substance.

- Blind staggers

-

Severe selenosis among animals, particularly livestock, characterized by impaired vision and an unsteady gait.

- Selenosis

-

Poisoning due to excessive intake of selenium.

- Thyroid-Specific Patient Reported Outcome (ThyPRO) questionnaire

-

The first thyroid disease-specific questionnaire developed to measure health-related quality of life across the spectrum of benign thyroid diseases.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Winther, K.H., Rayman, M.P., Bonnema, S.J. et al. Selenium in thyroid disorders — essential knowledge for clinicians. Nat Rev Endocrinol 16, 165–176 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0311-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0311-6

This article is cited by

-

A follow-up study on factors affecting the recovery of patients with hypothyroidism in different selenium environments

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2024)

-

Multifunctional nanoparticle-mediated combining therapy for human diseases

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024)

-

Selenopeptide nanomedicine ameliorates atherosclerosis by reducing monocyte adhesions and inflammations

Nano Research (2024)

-

The effect of selenium supplementation on sonographic findings of salivary glands in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) patients treated with radioactive iodine: study protocol for a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial

Trials (2023)

-

Use of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid and euthyroid patients: a 2022 THESIS questionnaire survey of members of the Latin American Thyroid Society (LATS)

Thyroid Research (2023)