Abstract

Interacting many-body systems in reduced-dimensional settings, such as ladders and few-layer systems, are characterized by enhanced quantum fluctuations. Recently, two-dimensional bilayer systems have sparked considerable interest because they can host unusual phases, including unconventional superconductivity. Here we present a theoretical proposal for realizing high-temperature pairing of fermions in a class of bilayer Hubbard models. We introduce a general and highly efficient pairing mechanism for mobile charge carriers in doped antiferromagnetic Mott insulators. The pairing is caused by the energy that one charge gains when it follows the path created by another charge. We show that this mechanism leads to the formation of highly mobile but tightly bound pairs in the case of mixed-dimensional Fermi–Hubbard bilayer systems. This setting is closely related to the Fermi–Hubbard model believed to capture the physics of copper oxides, and can be realized in currently available ultracold atom experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

One of the fundamental results in the theory of strongly interacting electron systems is the Kohn–Luttinger theorem, which states that electron pairing is inevitable in systems with purely repulsive interactions. Following the original paper by Kohn and Luttinger in 19651, it was commonly assumed that their pairing mechanism gives rise to critical temperatures that are too small to be observable in realistic experimental systems. The discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in cuprates2 triggered renewed interest in the study of pairing in systems with repulsive interactions. Even today, one key question in the field of cuprate superconductors is whether electron pairing in these materials can be explained by purely repulsive Coulomb interactions. The lack of theoretical consensus on this question motivated the development of the field of quantum simulation using ultracold atoms: the Fermi–Hubbard model, commonly believed to capture the main properties of cuprate superconductors, is naturally realized using fermions in optical lattices3,4,5. During the past few years, considerable experimental progress has been made in analysing the properties of this model, including the observation of long-range antiferromagnetic order6, magnetic polaron properties7, the crossover from polarons to Fermi liquids8 and bad metallic transport9. However, the demonstration of pairing has so far been out of reach as temperatures substantially below the superexchange would be required.

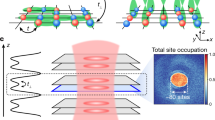

This Article has two goals. First we identify a microscopic bilayer model that features repulsive interactions between fermions, yet exhibits pairing at temperatures comparable to the superexchange, realizable by state-of-the art quantum simulators5 (Fig. 1). A special characteristic of this model is its mixed-dimensional (mixD) character: it features interlayer exchange interactions, but no interlayer single-particle tunnelling10,11 (Fig. 1a,b). Such systems can be realized experimentally using ultracold atoms by applying a potential gradient in bilayer and ladder models, which have been recently realized in cold atom experiments12,13,14,15.

We introduce an efficient pairing mechanism for distinguishable chargons with flavours μ = ± connected by a string Σ. a,b, The string pairing mechanism can be realized in a model of d-dimensional bilayers with spin-1/2 particles and strong repulsive interactions for d = 1 (a) and d = 2 (b). We consider mixD systems, where the hopping t⊥ between the layers is suppressed by a gradient Δ, while the superexchange J⊥ is kept intact and J⊥ ≫ J∣∣. The strong interlayer superexchange leads to the formation of rung singlets (dimers indicated by grey ellipses with red and blue spheres), depicted here for d = 1 (a) and d = 2 (b). The motion of doped holes (grey spheres) via t∥ within different layers μ = ± tilts the singlets along their paths, which corresponds to the formation of Σ. The potential energy associated with the string increases with its length as more singlets are tilted. Grey (green) shading corresponds to vertical (tilted) singlets. c,d, EB obtained by comparing the energies of spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon mesons in the GSP model, and the ground-state energy for a system with one versus two holes in DMRG as described in the text. We assumed that J∥/J⊥ = 0.01 and varies t∥/J⊥ in equation (4). In the DMRG, weak interlayer tunnelling of strength t⊥/J⊥ = 0.01 was added to ensure convergence. The shading indicates the tight binding and strong coupling regimes. c, EB for a 40 × 2 ladder (d = 1). d, EB for a bilayer system on a 12 × 4 cylinder.

The second goal of our paper is to reveal a general mechanism for pairing in doped antiferromagnetic Mott insulators (AFMI). It is based on the idea that a single hole can be understood as a bound state of chargon and spinon16,17,18,19,20, carrying the respective charge and spin quantum numbers of the underlying AFMI21,22,23,24,25, which are connected by a geometric string of displaced spins. The antiferromagnetic correlations (which may also be short-range) of the parent state are assumed to induce a linear string tension26. Within the same framework, a bound state of two holes corresponds to a bound state of two chargons. We demonstrate that the interplay of the potential energy, arising from the string tension, and kinetic energy of the partons leads to large binding energies for mesonic pairs of chargons. Our work goes beyond earlier analysis27,28,29,30,31 by including adverse effects that suppress pairing in a generic system. Effects detrimental to pairing will be suppressed in the mixD bilayer model we propose, featuring overwhelmingly attractive emerging parton interactions.

In the present work we focused on the case without interlayer tunnelling, t⊥ = 0, which enabled an effective theoretical description. We considered strong spin–charge coupling, where the intralayer tunnelling t∣∣ exceeds the relevant superexchange J⊥ (t∣∣ ≫ J⊥; Fig. 1). We demonstrate that the deeply bound pairs are highly mobile. This constitutes a notable exception from the common expectation32 that bipolarons should carry a heavy effective mass. The light mass of bipolarons is also significant, because it allows for high condensation temperatures Tc and has important implications for the ground state at finite doping: a light mass renders the localization of pairs unlikely. Therefore, we expect density wave states, such as stripes, to be less competitive with the superfluid states of pairs. In the opposite limit, t∣∣ ≪ J⊥, we also expect pairing, but in this case the pairs are heavy and thus Tc is low5.

The microscopic mixD bilayer model we studied hosts a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) regime with mobile but tightly bound pairs at low doping, and a Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) regime at high doping5. Hence our findings may have further implications for our understanding of the phenomenology of high-temperature superconductivity: when the interlayer couplings J⊥ are switched off, the bilayer systems we consider reduce to independent copies of the two-dimensional (2D) Fermi–Hubbard model. The latter is widely believed to capture the essential physics of the cuprate superconductors. Although experiments indicate that the cuprates do not realize a BEC phase with tightly bound Cooper pairs, they may be close in parameter space to models that exhibit a full BEC-to-BCS crossover. This would help to explain the pseudogap observed in cuprates, which is reminiscent of the pseudogap that arises at strong coupling in a BEC-to-BCS crossover, as realized in the mixD bilayer model.

String-based chargon pairing

The main result of this Article is the identification of a general string-based pairing mechanism for doped holes in AFMIs (Fig. 1). We begin by introducing a general formulation of the model, which we dub the dimer parton model, in an abstract way not tied to any microscopic Hamiltonian. We present the assumptions that went into the construction of the model and summarize its key predictions, and provide technical details in the Methods. In the following section we propose a microscopic bilayer model (Fig. 1a,b), and demonstrate that it realizes the abstract string scenario we envisioned. In particular, this allows us to understand the surprisingly high binding energies that we found for mobile (that is, strongly coupled) holes in 2D mixD bilayers shown in Fig. 1d.

In our general dimer parton model, we described excitations of AFMIs by two different types of parton, spinons and chargons, which carry the spin and charge quantum number, respectively. The partons also carry a flavour index μ = ±, allowing us to work with distinguishable chargons without a mutual hard-core constraint, which we predicted to pair up at strong couplings. The two different flavours μ = ± could, for example, be internal degrees of freedom or different layers in a bilayer system (Fig. 1). In the dimer parton model, we can treat arbitrary lattice geometries, but we assumed a homogeneous coordination number z for all sites; for example z = 4 for the bilayer system shown in Fig. 1b.

Furthermore, we considered rigid strings Σ on the underlying lattice, which connect the partons and fluctuate only through the motion of the latter. We assumed a linear string tension σ0; that is, a string is associated with an energy cost V(ℓΣ) = σ0ℓΣ proportional to its length ℓΣ, which reflects how the short-range antiferromagnetic correlations of the underlying AFMI are disturbed by the parton motion. In the microscopic mixD bilayer models discussed below (Fig. 1a,b), this string tension corresponds to the cost of breaking up rung singlets via the parton motion.

Since we considered rigid strings with a linear string tension, the partons are always confined in our model, forming mesonic states. The binding energy for two charges was hence obtained by comparing the ground state energy of a spinon–chargon (labelled sc) pair to the energy per chargon of a chargon–chargon (labelled cc) pair

At strong couplings (that is, when the hopping amplitude t ≫ σ0 of the holes exceeds the string tension σ0 ∝ J determined by the superexchange J), we predict a binding energy with a characteristic scaling

where α > 0 is a non-universal constant proportional to (z − 1)1/6 (see Methods for details).

Since a combination of t and σ0 ∝ J appears in equation (2), we predicted a remarkably strong asymptotic EB. The appearance of t in this expression highlights the key aspect of the underlying binding mechanism, where two chargons share one string and gain equal amounts of superexchange and kinetic energy: the motion of one chargon frustrates the underlying AFMI along the string Σ. In the case of two chargons, the second chargon can retrace the string created by the first, thus lowering the energy cost due to frustration in the spin sector. EB becomes positive because binding to a light second chargon with mass ∝ 1/t is favoured over binding two chargons individually to heavy spinons with mass ∝ 1/J.

In a 2D square lattice α ≈ 2 and using a string tension of σ0 ≈ J = 4t2/U, where U are on-site interactions, we expect a binding energy on the order of ∣EB∣ ≃ t1/3J2/3 ≃ 2.5t(t/U)2/3. This suggests that binding energies of a significant fraction of a typical tunnel coupling t may be possible, at least in principle, potentially exceeding room temperature.

As a second main result of the dimer parton model we estimated the effective mass of the chargon pair at strong couplings

Despite being tightly bound, the pair is highly mobile—contrary to common expectations for bipolarons.

We anticipate that the general string-based pairing mechanism plays a role in different microscopic models of AFMIs. Below, we discuss a specific realization in the mixD bilayer systems shown in Fig. 1.

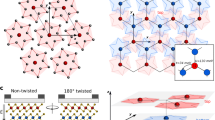

Microscopic model

We considered a bilayer of d-dimensional sheets with spin-1/2 particles \({\hat{{\mathbf{c}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{j}}}}},\mu ,\sigma }\), which can be either bosons or fermions. Here, μ, σ = ± are layer and spin indices, respectively, and j is a d-dimensional site index. In the following, we considered fermions. The particles were assumed to be strongly repulsive, allowing us to work in a subspace without double occupancies. The Hamiltonian we considered includes nearest-neighbour hopping t within the layers and spin-exchange couplings J∥, J⊥:

where \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\) projects to the subspace with maximum single occupancy per site; \({\hat{{{{{\mathbf{S}}}}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{j}}}}},\mu }\) and \({\hat{{\mathbf{n}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{j}}}}},\mu }\) denote the on-site spin and density operators, respectively, and h.c. denotes the Hermitian conjugate. The sum in the second line includes nearest-neighbour bonds within the layers, whereas the third line corresponds to bonds between the layers (Fig. 1b).

Experimentally, the model in equation (4) can be realized in d = 1, 2 starting from a Hubbard Hamiltonian5 with on-site interactions U. A strong interlayer gradient Δ can be used to obtain a mixD setting10 along the third direction where the two layers μ = ± are physically realized. Note that the antiferromagnetic coupling J⊥ > 0 can be realized both for fermions and bosons via an appropriate choice of the gradient Δ and the Hubbard interaction U33,34,35,36. In the following we assume that the interlayer spin-exchange is dominant, J⊥ ≫ ∣J∥∣, which can be achieved by choosing U ≫ t∣∣.

As a central result of our Article, we predict strong binding energies of holes, on the order of ∣EB∣ ≳ J⊥, in the strong coupling regime t∥ ≫ J⊥ where charges are highly mobile. In Fig. 1c,d we show binding energies obtained from density-matrix renormalization group (DMRG) simulations37 in mixD ladders (d = 1) and bilayers (d = 2) for J∥ = 0. The strong binding observed numerically can be explained by the string-based pairing mechanism introduced above.

The undoped ground state of equation (4) at half filling and for ∣J∥∣ ≪ J⊥ corresponds to a product of rung singlets

where V = Ld is the volume. Excitations correspond to the break up of singlets and dope the system with holes. The motion of a hole introduces tilted singlets along its path, directly imprinting the string Σ between two partons into the spin background. As illustrated in Fig. 1a,b, the mixD bilayer model naturally realizes spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon bound states.

Effective parton models

Now we discuss how the microscopic model, equation (4), can be related to effective parton models (see the Supplementary Information for a detailed derivation). We considered systems with two distinguishable partons, n = 1, 2, where the label n summarizes the set of properties layer μ, parton type (spinon or chargon) and spin σ. To obtain distinguishable partons, at least one of these properties has to be different between n = 1 and n = 2. We introduce the notation \(\left|{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{1},{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{2},{{\varSigma }}\right\rangle\), where Σ is a string of tilted singlets connecting x2 to x1, and xn are the positions of the partons.

Below, we discuss two parton models, the dimer parton model and the refined Gram–Schmidt parton (GSP) model. They can be related to the model in equation (4) within the following approximations (Supplementary Information):

-

(1)

The frozen-spin approximation38 neglects fluctuations of spins along Σ; this is justified by a separation of time scales when t∥ ≫ J⊥.

-

(2)

We neglect the effects of self-crossings of strings, which becomes exactly valid for large coordination numbers z ≫ 1 (or in ladders with d = 1). Even for a d = 2 square lattice bilayer, such effects are expected to be quantitatively small due to their small relative share of the string Hilbert space39.

-

(3)

In the dimer parton model, following the spirit of the Rokhsar–Kivelson quantum dimer model40, we assumed that spin configurations \(\left|{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{1},{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{2},{{\varSigma }}\right\rangle\) with parton positions x1,2 form an approximately orthonormal basis, \(\left\langle {{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{1}^{\prime},{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{2}^{\prime},{{\varSigma }}^{\prime} \right|\left.{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{1},{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{2},{{\varSigma }}\right\rangle \approx {\delta }_{{{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}_{2}}}}^{\prime},{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{2}}{\delta }_{{{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}_{1}}}}^{\prime},{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{1}}{\delta }_{{{\varSigma }}^{\prime} ,{{\varSigma }}}\) where ẟ denotes the Kronecker delta, which is justified by the small overlaps of configurations with non-identical singlet configurations. This leads to an effective dimer parton Hamiltonian with nearest-neighbour hopping of the partons under simultaneous adaption of the string states, and a string potential VΣ.

The third approximation differs between the dimer parton and the GSP models. In the GSP model, the assumption that string states form an orthonormal basis is partially dropped. To this end, we performed a Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization of the string states defined in the t–J Hilbert space and accounted for the non-orthogonal nature of spinon–chargon states, up to loop effects (Supplementary Information). This led to an accurate prediction of the spinon dispersion. For chargon–chargon states, the GSP and dimer parton models are equivalent.

In the parton models, for simplicity, we assumed a linear string potential, \({V}_{{{\varSigma }}}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}={\sigma }_{0}\,{\ell }_{{{\varSigma }}}\), where ℓΣ is the length of string Σ. For the tilted singlets in the mixD bilayer setting, equation (4), the linear string tension is σ0 = 3/4J⊥, corresponding to the energy difference between a singlet and a random spin configuration. In the chargon–chargon case, the string potential has an additional on-site attraction, \({V}_{{{\varSigma }}}^{{{{\rm{cc}}}}}={V}_{{{\varSigma }}}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}-{\delta }_{{{\varSigma }},0}{J}_{\perp }/4\), which leads to slightly stronger binding than that predicted by equation (2).

Two holes are distinguishable if they move within separate layers μ1 = −μ2, and they can thus occupy the same position x in the lattice. Note that the motion of a second hole in the opposite layer and along the same path can completely remove the geometric string Σ of displaced spins.

Numerical results

In Fig. 1c we show the EB predicted by the GSP model for the mixD ladder (d = 1). Plotting the results over \({({t}_{\parallel }/{J}_{\perp })}^{1/3}\) shows that EB at strong couplings, t∥ > J⊥, scales as \(| {E}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}| \simeq {t}_{\parallel }^{1/3}{J}_{\perp }^{2/3}\) as predicted by the dimer parton model. In the opposite tight binding regime, t∥ ≪ J⊥, we found excellent agreement with our perturbative result from ref. 5 (see the dash-dotted line in Fig. 1c). For our DMRG simulations, we defined the binding energy as EB = 2E1 − (E0 + E2), where EN is the ground state energy of the state with N holes. Our DMRG results are in excellent agreement with our prediction from the GSP model for couplings t∥/J⊥ ranging over several orders of magnitude, from 0.1 to >30.

In Fig. 1d, we show our results for the mixD bilayer system (d = 2). From the dimer parton model we again expected strong pairing when t∥ ≫ J⊥. This prediction was confirmed by our DMRG results in 2 × 12 × 4 systems, where the first direction denotes the two layer indices and we assumed periodic (open) boundary conditions along the short (long) axes of the cylinder. For t∥/J⊥ = 3 we found remarkably strong EB below J⊥. For small t∥/J⊥ ≪ 1, the perturbative tight binding result5 was obtained.

We also compared predictions made by the GSP model with DMRG results for d = 2. In Fig. 2 we show the energies per hole in the spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon cases, respectively, and obtained very good agreement. However, a small deviation of a few per cent could be observed at strong couplings in the two-hole case, where the GSP and dimer parton models were identical. We expect that loop effects, ignored in the parton models, led to the slightly lower energy per hole found by DMRG. Since EB, shown in Fig. 1d, was obtained as the small difference between the large one- and two-hole energies, see equation (2), the deviation of the GSP model from DMRG seems sizable at strong couplings. We emphasize, however, that GSP and DMRG consistently predicted positive EB throughout, and a crossover from tightly bound to strongly fluctuating extended pairs of holes.

Signatures of parton formation in one- and two-hole spectra

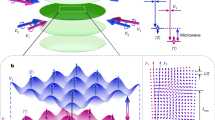

To further corroborate the parton structure of the one- and two-hole states we found at strong coupling and demonstrate the high degree of mobility of the paired states, we investigated their spectral properties. We performed time-dependent DMRG simulations41,42,43 in the mixD ladder (d = 1) and bilayer (d = 2) to extract the following spectral functions A

with frequency ω, wavevector k and where \(\left|{\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) (E0) is the ground state (energy) without holes, and \(\left|{\psi }_{n}^{(1/2)}\right\rangle\) (\({E}_{n}^{(1/2)}\)) are the eigenstates (energies) with one (two) holes. The excitations are created through the operators \({\hat{{\mathbf{C}}}}_{(1/2),{{{{\mathbf{k}}}}}}\), which are defined as the Fourier transforms of \({\hat{{\mathbf{C}}}}_{1,{{{{\mathbf{i}}}}}}={\hat{{\mathbf{c}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{i}}}}},+,\uparrow }\) and \({\hat{{\mathbf{C}}}}_{2,{{{{\mathbf{i}}}}}}={\hat{{\mathbf{c}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{i}}}}},+,\uparrow }{\hat{{\mathbf{c}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{i}}}}},-,\downarrow }\) (see insets in Fig. 3a,b).

a–c, Spectra for one hole (a) and two holes (b) in a ladder (d = 1) and two holes in a mixD bilayer (d = 2) (c). In a and b, we assumed that t∥/J⊥ = 3.4 and J∥/J⊥ = 0.31; and in c that t∥/J⊥ = 2 and J∥/J⊥ = 0.01. In our time-dependent DMRG (colour map) we added weak tunnelling t⊥/J⊥ = 0.01 to simplify convergence. The dashed lines in a and b correspond to eigen energies of the GSP model (Supplementary Information), where only states with even inversion symmetry are shown. The observed discrete spectral lines correspond to vibrational excitations of emerging spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon mesons in the system. The dashed lines in c describe GSP spectra broadened by the Fourier resolution of our time-dependent DMRG simulations (solid lines). Red (blue) lines correspond to momenta k = 0 (k = π).

Our results in Fig. 3a,b for the ladder (d = 1) reveal a series of narrow lines that are visible up to high energies, in both the one-hole (Fig. 3a) and two-hole (Fig. 3b) spectra. They correspond to long-lived vibrational excitations of the spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon mesons, respectively. This intuition was confirmed by the excellent agreement we obtained with energies predicted by the GSP model. In the Supplementary Information, we show that the parton model also captures the spectral weights. The existence of discrete internal excitations, as revealed in Fig. 3, is a hallmark of emerging mesonic states in doped AFMIs. In addition to the vibrational states visible in Fig. 3, we also predicted odd-parity spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon states25 from the parton model, whose spectral weights are negligible in Fig. 3 (Supplementary Information).

For the two-hole case (Fig. 3b), we observed a strong centre-of-mass dispersion. This indicated that the deeply bound pair was highly mobile, confirming a key prediction of the parton model equation (3). Additionally, at kx = π the relative motion of the partons is suppressed by quantum interference, and only the lowest mesonic state has non-vanishing spectral weight.

The parameter set we used in Fig. 3a,b assumed that J∥/J⊥ = 0.31 and corresponded to a situation that could be realistically realized in a Ferm–Hubbard ladder with a potential gradient between the two legs5. Hence, the emerging spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon meson states we predicted in our model should be experimentally accessible with ultracold atoms in optical lattices with current technology.

In Fig. 3c we show two-hole spectral cuts at rotationally invariant momenta k = 0 = (0, 0) and π = (π, π) for the mixD bilayer where d = 2; we considered t∥/J⊥ = 2 in the strong coupling regime. Here, our underlying time-dependent DMRG simulations on a 2 × 40 × 4 cylinder were more challenging and we reached shorter times than in d = 1. This resulted in significant Fourier broadening, and prevented us from identifying individual vibrational excitations at high energies. Nevertheless, at k = 0 a first peak was visible in the DMRG data. Comparison with a broadened GSP model spectrum suggested that this peak probably corresponds to the first vibrational meson state.

At k = π, the two-hole spectrum in Fig. 3c collapsed to a single peak. As in d = 1 at k = π, this can be understood within the dimer parton model from destructive quantum interference that leads to a cancellation of the chargon’s relative motion. The energy of the tightly bound two-hole state at k = π was accurately predicted by the GSP model.

As suggested by the large energy difference of the chargon–chargon state between k = 0 and k = π, on the order of 6t∥ in Fig. 3c, we found that the deeply bound state at k = 0 had a light effective mass. A fit \({k}_{x}^{2}/(2{M}_{{{{\rm{cc}}}}})\) to the lowest spectral peak Ecc(kxex) − Ecc(0) yielded Mcc = 2.44/t∥ at t∥/J⊥ = 2. This compares reasonably with our estimate Mcc ≥ 0.63/t∥ from the dimer parton model; we used an improved version of equation (3) (Supplementary Information). This result should be contrasted with the much heavier Mcc = 25/J⊥ in the tight binding regime5, at t∥/J⊥ = 0.1 with a comparable EB on the order of ∣EB∣ ≈ 3/4J⊥.

Finite-temperature phase diagram

At finite temperatures, the emergence of two kinds of mesons can lead to rich physics. Although the ground states we found are always paired, we expected a mixture of spinon–chargon and chargon–chargon pairs in chemical equilibrium when T > 0. Because a gas of N spinon–chargon pairs has more entropy than a gas of N/2 chargon–chargon pairs at high T, we expected a crossover from spinon–chargon to chargon–chargon domination around some temperature Tmix.

In d ≥ 2 dimensions, we expected an even richer phase diagram. The chargon–chargon pairs can form a (quasi-) condensate below the respective temperature (TBKT) Tc in (d = 2) d > 2 dimensions at finite doping and before spinon–chargon pairs dominate beyond Tmix. Furthermore, at a critical temperature T* on the order of J⊥ we expect a thermal deconfinement transition of the mesons to take place when d ≥ 2 (ref. 44).

Discussion and outlook

We introduced a general string-based pairing mechanism for distinguishable chargons in AFMIs, and demonstrated that the resulting binding energy scales as ∣EB∣ ≃ t1/3J2/3, or ∣EB∣ ≃ t(t/U)2/3, when t ≫ J. The highest binding energies are expected when the chargon–chargon mesons become extended, with an average string length scaling as ℓ ≃ (t/J)1/3 (ref. 27; see also the Supplementary Information). We confirmed the validity of our analytical arguments using DMRG simulations of bilayer toy models that can be realized experimentally using, for example, ultracold atoms in optical lattices5. Another interesting situation corresponds to cuprate materials with a multilayer structure and an effective chemical potential offset between the layers45,46: starting from half filling, we expect that a strong pump pulse may allow the creation of metastable pairs of doublons and holes in opposite layers. These may then form the mesonic bound states that we propose, and could be probed by a subsequent laser pulse.

The analysis we performed here was limited to individual mesons, but our prediction of deeply bound and highly mobile chargon pairs for t ≫ J has important implications at finite doping. In such a regime, we expect a quasi-condensate with power-law correlations below a critical BKT temperature TBKT. for the mixD bilayer (d = 2). Owing to the high mobility of the chargon–chargon pairs, a sizable TBKT at a fraction of t and robustness against localization are expected.

Another interesting direction would be the investigation of an emergent SO(5) symmetry in the bilayer models, see refs. 47,48 for studies using a related model.

Methods

String-based chargon pairing

Here we introduce the general string-based pairing mechanism for an idealized parton model of AFMIs in d dimensions (the dimer parton model). We considered two flavours of chargons \({\hat{{\mathbf{h}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}},\mu }\) with μ = ±, which allowed us to work with distinguishable chargons; \({{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}^{d}\) denotes a lattice vector. The two different flavours μ = ± could, for example, be internal degrees of freedom or different layers in a bilayer system (Fig. 1). In the dimer parton model, we can treat arbitrary lattice geometries (in principle), but we assumed a homogeneous coordination number z for all sites; for example z = 4 for the bilayer system shown in Fig. 1b. We note that the coordination number considered here is from the point of view of the hopping charges, which are confined to the 2D planes and therefore have the same coordination number as in a square lattice. We also introduced 2 × 2 flavours of spinons, \({\hat{{\mathbf{f}}}}_{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}},\mu ,\sigma }\), where σ = ± denotes the spin index.

Furthermore, we considered rigid strings Σ on the underlying lattice, which connect the partons and fluctuate only through the motion of the latter. In our idealized scenario, we assumed that such geometric strings retain a full memory of the parton trajectories up to self-retracing paths, but including loops. These strings can also be viewed as a manifestation of the gauge fluctuations expected from any parton representation of an AFMI.

We worked in a regime of low parton density and considered only isolated pairs of two distinguishable partons, n = 1, 2. Hence, their quantum statistics played no role in the following. The label n summarizes the set of μ, parton type (spinon or chargon) and spin σ in the case of a spinon. To obtain distinguishable partons, at least one of these properties has to be different between n = 1 and n = 2. We can write the orthonormal basis states of the dimer parton model as \(\left|{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{1},{{{{{\mathbf{x}}}}}}_{2},{{\varSigma }}\right\rangle\), where Σ connects x2 to x1; that is:

The effective Hamiltonian of the two partons written in first quantization reads

The first line describes nearest-neighbour hopping of the partons, with amplitudes 1/2mn, and simultaneous adaption of the string state from Σ to \({{{\Sigma }}}_{{{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}_{n},{{{{\boldsymbol{y}}}}}_{n},{{\Sigma }}}^{\prime}\): hopping along the existing string leads to a retraction of the string along yn − xn, otherwise the string is extended by the same element. Extensions to next-nearest-neighbour hopping can also be considered. The second line in equation (8) describes a general string potential VΣ that we assume to be independent of the parton flavours.

In the following we consider a linear string potential

In a weakly doped AFMI we may assume that σ0 ≃ J is proportional to J (refs. 21,25). Furthermore, we assumed that the parton masses strongly depended on flavour in the following way

That is the chargon mass mh is significantly lighter than the spinon mass mf, since t ≫ t2/U ≃ J in AFMIs.

Our goal in the following is to demonstrate that two distinguishable chargons (that is, with different μ) form a strongly fluctuating pair with a large EB when t ≫ J. Since we considered rigid strings with a linear string tension, the partons were always confined in our model. Hence EB for two charges was obtained by comparing mesonic states constituted by a spinon–chargon and a chargon–chargon pair, respectively:

First, we considered spinon–chargon mesons. Because 1/mf ≃ J, we could treat the spinon motion perturbatively and start from a localized spinon. In this case, all charge fluctuations are described by nearest-neighbour tunnelling between adjacent string configurations, and equation (8) becomes a single-particle hopping problem on the Bethe lattice \({\hat{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{2p}}}}}{| }_{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}=-t{\sum }_{\langle {{\varSigma }}^{\prime} ,{{\varSigma }}\rangle }\left(\left|{{\varSigma }}^{\prime} \right\rangle \left\langle {{\varSigma }}\right|+\,{{\mbox{h.c.}}}\,\right)+{\sigma }_{0}{\sum }_{{{\varSigma }}}{\ell }_{{{\varSigma }}}\left|{{\varSigma }}\right\rangle \left\langle {{\varSigma }}\right|+{{{\mathcal{O}}}}(J)\) (Fig. 1a). Its spectrum is composed of decoupled rotational and vibrational sectors39. The ground state has no rotational excitations, and its energy in the limit t ≫ J follows the well-known universal form27

where α > 0 is a non-universal constant proportional to (z − 1)1/6. Note that contributions from the spinon motion are contained in corrections \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}(J)\).

Next we considered chargon–chargon mesons composed of a pair, μ = ±, of two distinguishable chargons. We then needed to include the dynamics of both partons in equation (8). Since \({\hat{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{2p}}}}}\) is translationally invariant, we can transform to the co-moving frame of the first parton x1 by a Lee–Low–Pines transformation49. For a given centre-of-mass quasimomentum k from the Brillouin zone corresponding to the underlying lattice, one again obtains a hopping problem on the Bethe lattice. Although the contributions from the string potential and from x2 were identical to the spinon–chargon case, the motion of the first chargon contributes additional k-dependent terms that tend to frustrate the motion of the pair for k ≠ 0 (ref. 28).

Around the dispersion minimum at k = 0 we obtained

up to corrections of order \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}({{{{{\mathbf{k}}}}}}^{2})\) (Supplementary Information). The only difference from the spinon–chargon problem is that t → 2t has been replaced by twice the chargon tunnelling. This replacement can be easily understood by noting that the relative motion of the two chargons involves the reduced mass, 1/mred = 2/mh; that is, tred = 2t. Thus we obtained the energy of the chargon–chargon meson by using the same scaling result as in the spinon–chargon case, equation (12), and merely replacing t → 2t. It is important to note that this leaves the non-universal constant α unchanged, and we obtained

Now we were in a position to calculate EB, equation (11), of two holes in the limit t ≫ J. While the kinetic zero-point energies ∝ −t(z−1)1/2 cancel, the leading-order string binding energies \(\propto {t}^{1/3}{\sigma }_{0}^{2/3}\) yield

This is a remarkably strong EB, which depends on a combination of t and σ0 ≃ J. The appearance of t in this expression highlights the underlying binding mechanism, where two chargons share one string, gaining equal amounts of potential and kinetic energy.

Finally, we estimated the effective mass of the chargon pair on a hypercubic lattice. We made a translationally invariant ansatz for the chargon–chargon meson in the co-moving frame of the first chargon, and expand the variational energy up to order k2. As shown in the Supplementary Information, for t ≫ J this yields a centre-of-mass dispersion k2/2Mcc of the pair, with

Despite being tightly bound, the pair is highly mobile—contrary to common expectations for bipolarons.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The data analysed in the current study has been obtained using the open-source tenpy package; this DMRG code is available via GitHub at https://github.com/tenpy/tenpy and the documentation can be found at https://tenpy.github.io/#.

References

Kohn, W. & Luttinger, J. M. New mechanism for superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 524–526 (1965).

Bednorz, J. G. & Müller, K. A. Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba–La–Cu–O system. Z. Phys. B 64, 189–193 (1986).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Zwerger, W. Many-body physics with ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 885–964 (2008).

Tarruell, L. & Sanchez-Palencia, L. Quantum simulation of the hubbard model with ultracold fermions in optical lattices. C. R. Phys. 19, 365–393 (2018).

Bohrdt, A., Homeier, L., Reinmoser, C., Demler, E. & Grusdt, F. Exploration of doped quantum magnets with ultracold atoms. Ann. Phys. 435, 168651 (2021).

Mazurenko, A. et al. A cold-atom Fermi–Hubbard antiferromagnet. Nature 545, 462–466 (2017).

Koepsell, J. et al. Imaging magnetic polarons in the doped Fermi–Hubbard model. Nature 572, 358–362 (2019).

Koepsell, J. et al. Microscopic evolution of doped Mott insulators from polaronic metal to Fermi liquid. Science 374, 82–86 (2021).

Brown, P. T. et al. Bad metallic transport in a cold atom Fermi–Hubbard system. Science 363, 379–382 (2019).

Grusdt, F., Zhu, Z., Shi, T. & Demler, E. Meson formation in mixed-dimensional t–J models. SciPost Phys. 5, 057 (2018).

Grusdt, F. & Pollet, L. \({{\mathbb{z}}}_{2}\) parton phases in the mixed-dimensional t−Jz model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 256401 (2020).

Koepsell, J. et al. Robust bilayer charge pumping for spin- and density-resolved quantum gas microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 010403 (2020).

Hartke, T., Oreg, B., Jia, N. & Zwierlein, M. Doublon-hole correlations and fluctuation thermometry in a Fermi–Hubbard gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 113601 (2020).

Gall, M., Wurz, N., Samland, J., Chan, C. F. & Köhl, M. Competing magnetic orders in a bilayer Hubbard model with ultracold atoms. Nature 589, 40–43 (2021).

Sompet, P. et al. Realising the symmetry-protected haldane phase in Fermi-Hubbard ladders. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.10421 (2021).

Read, N. & Newns, D. M. A new functional integral formalism for the degenerate Anderson model. J. Phys. C 16, 1055–1060 (1983).

Coleman, P. New approach to the mixed-valence problem. Phys. Rev. B 29, 3035–3044 (1984).

Coleman, P. Mixed valence as an almost broken symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 35, 5072–5116 (1987).

Wen, X.-G. & Lee, P. A. Theory of underdoped cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 503–506 (1996).

Vijayan, J. et al. Time-resolved observation of spin-charge deconfinement in fermionic Hubbard chains. Science 367, 186–189 (2020).

Béran, P., Poilblanc, D. & Laughlin, R. B. Evidence for composite nature of quasiparticles in the 2D t–J model. Nucl. Phys. B 473, 707–720 (1996).

Laughlin, R. B. Evidence for quasiparticle decay in photoemission from underdoped cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 1726–1729 (1997).

Senthil, T., Sachdev, S. & Vojta, M. Fractionalized Fermi liquids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 216403 (2003).

Bohrdt, A., Demler, E., Pollmann, F., Knap, M. & Grusdt, F. Parton theory of angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy spectra in antiferromagnetic Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035139 (2020).

Bohrdt, A., Demler, E. & Grusdt, F. Rotational resonances and Regge trajectories in lightly doped antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 197004 (2021).

Chiu, C. S. et al. String patterns in the doped Hubbard model. Science 365, 251–256 (2019).

Bulaevskii, L. N., Nagaev, É. L. & Khomskii, D. I. A new type of auto-localized state of a conduction electron in an antiferromagnetic semiconductor. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 27, 836–838 (1968).

Trugman, S. A. Interaction of holes in a Hubbard antiferromagnet and high-temperature superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 37, 1597–1603 (1988).

Shraiman, B. I. & Siggia, E. D. Two-particle excitations in antiferromagnetic insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 740–743 (1988).

Manousakis, E. String excitations of a hole in a quantum antiferromagnet and photoelectron spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 75, 035106 (2007).

Vidmar, L. & Bonca, J. Two holes in the t–J model form a bound state for any nonzero J/t. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 26, 2641–2645 (2013).

Kivelson, S. High-Tc superconductivity after 1/3 of 100 years. Harvard CMSA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Q8GvzJT-aM (2020).

Duan, L. M., Demler, E. & Lukin, M. D. Controlling spin exchange interactions of ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 090402 (2003).

Trotzky, S. et al. Time-resolved observation and control of superexchange interactions with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Science 319, 295–299 (2008).

Dimitrova, I. et al. Enhanced superexchange in a tilted Mott insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 043204 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. Realization of a bosonic antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 17, 990–994 (2021).

Hauschild, J. & Pollmann, F. Efficient numerical simulations with tensor networks: Tensor Network Python (TeNPy). SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 5 https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysLectNotes.5 (2018).

Grusdt, F., Bohrdt, A. & Demler, E. Microscopic spinon-chargon theory of magnetic polarons in the t−J model. Phys. Rev. B 99, 224422 (2019).

Grusdt, F. et al. Parton theory of magnetic polarons: mesonic resonances and signatures in dynamics. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011046 (2018).

Rokhsar, D. S. & Kivelson, S. A. Superconductivity and the quantum hard-core dimer gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2376–2379 (1988).

Kjäll, J. A., Zaletel, M. P., Mong, R. S. K., Bardarson, J. H. & Pollmann, F. Phase diagram of the anisotropic spin-2 XXZ model: infinite-system density matrix renormalization group study. Phys. Rev. B 87, 235106 (2013).

Zaletel, M. P., Mong, R. S. K., Karrasch, C., Moore, J. E. & Pollmann, F. Time-evolving a matrix product state with long-ranged interactions. Phys. Rev. B 91, 165112 (2015).

Paeckel, S. et al. Time-evolution methods for matrix-product states. Ann. Phys. 411, 167998 (2019).

Hahn, L., Bohrdt, A. & Grusdt, F. Dynamical signatures of thermal spin-charge deconfinement in the doped Ising model. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.09732 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Anomalous Fermi-surface dependent pairing in a self-doped high-Tc superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 236401 (2006).

Shimizu, S. et al. Uniform mixing of antiferromagnetism and high-temperature superconductivity in electron-doped layers of four-layered Ba2Ca3Cu4O8F2: a new phenomenon in an electron underdoped regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 257002 (2007).

Scalapino, D., Zhang, S.-C. & Hanke, W. SO(5) symmetric ladder. Phys. Rev. B 58, 443–452 (1998).

Demler, E., Hanke, W. & Zhang, S.-C. SO(5) theory of antiferromagnetism and superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 909–974 (2004).

Lee, T. D., Low, F. E. & Pines, D. The motion of slow electrons in a polar crystal. Phys. Rev. 90, 297–302 (1953).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Greiner, J. Koepsell, G. Salomon, C. Gross, S. Hirthe, D. Bourgund, L. Hahn, Z. Zhu, L. Pollet and U. Schollwöck for fruitful discussions. This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC-2111—390814868, by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 948141), by the NSF through a grant for the Institute for Theoretical Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics at Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, the Harvard-MIT CUA, ARO grant number W911NF-20-1-0163 and the National Science Foundation through grant number OAC-1934714.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. A.B. performed all numerical DMRG simulations. L.H., F.G. and A.B. derived the effective parton model. A.B. and F.G. proposed the study of string-based pairing in mixed dimensions and all authors contributed to the conceptual ideas.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Martin Garttner and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary discussion, derivations and figures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bohrdt, A., Homeier, L., Bloch, I. et al. Strong pairing in mixed-dimensional bilayer antiferromagnetic Mott insulators. Nat. Phys. 18, 651–656 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01561-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01561-8

This article is cited by

-

Exotic pairing of charge carriers seen in a quantum simulation

Nature (2023)

-

Dichotomy of heavy and light pairs of holes in the t−J model

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Magnetically mediated hole pairing in fermionic ladders of ultracold atoms

Nature (2023)

-

Quantifying hole-motion-induced frustration in doped antiferromagnets by Hamiltonian reconstruction

Communications Materials (2023)

-

Attraction Versus Repulsion Between Doublons or Holons in Mott-Hubbard Systems

International Journal of Theoretical Physics (2023)