Abstract

Jupiter’s atmosphere is one of the most turbulent places in the solar system. Whereas observations of lightning and thunderstorms point to moist convection as a small-scale energy source for Jupiter’s large-scale vortices and zonal jets, this has never been demonstrated due to the coarse resolution of pre-Juno measurements. The Juno spacecraft discovered that Jovian high latitudes host a cluster of large cyclones with diameter of around 5,000 km, each associated with intermediate- (roughly between 500 and 1,600 km) and smaller-scale vortices and filaments of around 100 km. Here, we analyse infrared images from Juno with a high resolution of 10 km. We unveil a dynamical regime associated with a significant energy source of convective origin that peaks at 100 km scales and in which energy gets subsequently transferred upscale to the large circumpolar and polar cyclones. Although this energy route has never been observed on another planet, it is surprisingly consistent with idealized studies of rapidly rotating Rayleigh–Bénard convection, lending theoretical support to our analyses. This energy route is expected to enhance the heat transfer from Jupiter’s hot interior to its troposphere and may also be relevant to the Earth’s atmosphere, helping us better understand the dynamics of our own planet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) on board Juno, operating at 4.8 μm and capturing ammonia clouds1,2, revealed a set of weather phenomena present at Jovian high latitudes1,3. In contrast to mid-latitude cloud bands and zonal jets, the dominant features are numerous vortices of varying size (Fig. 1), including a cluster of large cyclonic vortices (eight in the north and five in the south) surrounding a single polar cyclone, located at about ±83°. These cyclones have a diameter of ~5,000 km, peak speeds of 100 m s−1 and a fast rotation period of ~10 h, and have endured since their discovery in 20171,3,4. Intermediate-scale cyclones and anticyclones, with a diameter of ~1,000 km and less, have a similar rotation period. The smallest observable vortices and filaments (<100 km) survive a couple of hours to several days only3 and are the signature of an intense cloud activity3,4 (Fig. 1). Lightning reported at northern latitudes in recent studies5,6,7, especially above the 2-bar level7, points to moist convection within ammonia clouds as a powerful source of energy in Jupiter’s polar regions. However, even though the dynamical link between small-scale moist convection and large-scale vortices has been investigated at high latitudes in recent modelling studies8,9,10,11, it has never been supported by observations.

Brightness temperature, corrected for nadir viewing, ranges from 206 K (darkest colour) to 227 K (brightest colour). The dashed circle at 80° N is about 12,000 km from the pole. The area analysed in this paper is highlighted by the black rectangle and captures the polar cyclone, parts of the circumpolar cyclones at 45°, 100°, 220° and 260° W, as well as two smaller anticyclones (that is, the dark features) at 210–240° W, which are joined by a streamer.

Here, we investigate this link using high-resolution infrared images taken by JIRAM at the north pole of Jupiter on 2 February 2017, from which two complementary datasets are derived. First, we use wind velocities (Extended Data Fig. 1a) derived by tracking clouds in sequence of infrared images (see ref. 4 for the methodology) in a domain greater than 7,000 × 20,000 km (Fig. 1, black rectangle), where overlapping observations over short intervals are available. The wind field has a resolution of 10 km, which is slightly higher than previous measurements12. Second, the optical depth, defined as log(I0/I), with I the brightness and I0 = 0.55946 W m−2 the maximum brightness, is directly obtained from the infrared measurements3 with the same resolution as the wind field (Fig. 2a). Optical depth is related to variations in cloud thickness such that thick cloud produces high optical depth3,13.

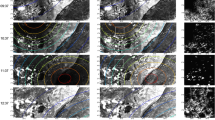

a–c, Mosaic of optical thickness anomaly τ derived directly from the infrared observations, defined as \(\tau ={{{{\mathrm{log}}}}}(I_{{{{\rm{0}}}}}/I)-\overline{{{{{\mathrm{log}}}}}(I_{{{{\rm{0}}}}}/I)}\), with the overbar indicating the domain average (a), large-scale relative vorticity ζ derived from the wind measurements (Extended Data Fig. 1a) after application of a low-pass filter that retains length scales greater than 1,600 km (that is, wavenumbers k < 6 × 10−4 cpkm) (b) and small-scale relative vorticity ζτ derived from τ after application of a high-pass filter that retains length scales smaller than 1,600 km (that is, wavenumbers k > 6 × 10−4 cpkm, Methods) (c). As ζτ is directly related to cloud thickness, it is the signature of cloud convection. Large-scale vortices in b gain their energy from small-scale vortices in c via an upscale energy transfer (Main).

The analysis of these two unique datasets using a theoretical framework (the surface quasi-geostrophy (SQG) framework14,15,16,17,18, described in Moist convection is a KE source at 100 km scales section) allows us to uncover a dynamical regime on Jupiter, which highlights the key role played by moist convection at Jovian high latitudes. Surprisingly, this regime is reminiscent of idealized studies of rapidly rotating Rayleigh–Bénard convection19,20,21,22,23,24 and laboratory experiments25 and even resembles parts of the Earth’s atmosphere26,27,28.

Dynamical context

We analyse the properties of the wind measurements in terms of kinetic energy (KE), relative vorticity (ζ, that is, the local rate of spin of a vortex, Methods) and horizontal divergence (χ, Methods). The magnitude of ζ (Extended Data Fig. 1b) and χ (Extended Data Fig. 1c) reaches the local spin rate of the planet (f = 3.5 × 10−4 s−1, also called the Coriolis parameter), which is one fold higher than previous estimates29. First, we use a suite of spectral analyses (Methods) to investigate how KE, ζ and χ are distributed among length scales and what their spectral characteristics tell us about the underlying dynamical regime (Methods). The KE spectrum (Fig. 3a) exhibits two distinct scale ranges separated by a conspicuous spectral slope discontinuity: scales larger than 1,600 km are characterized by a steep slope in k−3 (with k the wavenumber), whereas scales smaller than 1,600 km are characterized by a shallower slope in k−4/3. This discontinuity is even more striking in ζ’s power spectrum (Fig. 3b, blue curve) since the slope changes sign at 1,600 km. Second, we retrieve the physical patterns captured by each scale range using a spectral filter (Methods). As expected, the ζ field associated with the k−3 scale range comprises the large vortices, including the persistent circumpolar and polar cyclones, as well as one large anticyclone (Fig. 2b). Since the χ spectral amplitude is a lot smaller than the ζ spectral amplitude in this scale range (Fig. 3b), large scales are likely governed by 2D turbulence30. The Rossby number, defined as Ro = ζ/f, reaches 0.5 and its distribution is positively skewed (Extended Data Fig. 2b), confirming the overwhelming dominance of the large cyclones in the k−3 scale range. In contrast, the k−4/3 scale range (length scales of ~100–1,600 km) includes numerous cyclones, anticyclones and elongated filaments embedded in between the vortices (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Unlike the k−3 scale range, χ and ζ variances are of the same order of magnitude, and are even equal for scales smaller than 300 km (Fig. 3b,c), suggesting that vortices in this scale range are forced by vertical motions and hence that their dynamics is three dimensional31. Finally, the Ro distribution is only slightly negatively skewed (Extended Data Fig. 2c), highlighting the absence of a cyclone–anticyclone preference in the k−4/3 scale range.

a, Power spectra density (PSD) of KE (blue curve) and APE (orange curve). b, PSD of relative vorticity (ζ, blue curve), horizontal divergence (χ, green curve) and vorticity derived from τ (ζτ, orange curve). See Extended Data Fig. 1b,c for ζ and χ in physical space. A spectral slope discontinuity in KE and ζ occurs at 6 × 10−4 cpkm (~1,600 km), highlighted by the thin vertical dashed line. Thick dashed lines show spectral slopes obtained by curve fitting. c, χ-to-ζ power spectra ratio χPSD/ζPSD. The thin horizontal dashed line indicates a ratio of 1.

Overall, the analysis of the wind measurements highlights a turbulent regime that involves two classes of vortices separated by a conspicuous spectral slope discontinuity (Fig. 3a,b, blue curve) between large-scale vortices for which the surface dynamics is probably driven by horizontal motions and smaller vortices and filaments affected by vertical motions. However, vorticity and divergence diagnosed from the wind measurements contain small-scale noise (≲100 km, Extended Data Fig. 1b,c) as their computation involves both spatial and temporal derivatives. This noise prevents us from analysing the link between small-scale features and large-scale vortices solely from the wind measurements.

Moist convection is a KE source at 100 km scales

We use the information provided by the optical depth anomaly, τ, in combination with the wind measurements. Positive values of τ correspond to thick clouds (that is, updraughts) and negative values to no or thin clouds (that is, downdraughts)3,13,32. Thus, τ can be interpreted as the signature of vertical motions and therefore as a vertical scale. Based on the assumption that cloud thickness is an indicator of tropopause height anomalies (as for the Earth’s tropopause15), tropopause height anomalies are estimated as h = H0τ, where H0 is the length scale of tropopause height anomalies. Then, τ can be interpreted in terms of APE, defined as N2h2, with N the Brunt–Väissälä frequency (Methods). APE and KE spectra have the same slope (k−4/3) for scales <1,600 km, which is reminiscent of the dynamical SQG framework14,15,16,17,18 (Methods). In the next paragraph, we use this framework and focus on the k−4/3 scale range to better understand the properties of the intermediate- and small-scale vortices.

In SQG, APE and KE spectra are identical, which leads to simple relationships between horizontal motions and h (ref. 18). As the SQG framework is relevant for the Earth’s tropopause14,15,17,18,27, we assume that it also applies to Jupiter. We adjust the APE spectral amplitude to match that of KE for scales <1,600 km by taking N constant and equal to 4 × 10−3 s−1 in Jupiter’s upper troposphere33 and choosing H0 = 9 km (Fig. 3a). Using SQG properties, relative vorticity can be diagnosed from τ (equation (10)). This relative vorticity field, ζτ, is displayed in Fig. 2c. As expected, ζ and ζτ spectra overlap in the k−4/3 scale range (Fig. 3b, orange and blue curves). To validate our assumption that SQG applies in the k−4/3 scale range, we now compare ζ and ζτ in physical space after application of a conservative band-pass filter that retains only length scales between 250 and 1,600 km (see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 3b,c for the filtered fields). Although ζ is noisier than ζτ (Methods), the correspondence between the two fields is striking, especially where ζ is well resolved. For instance, the streamer between the two anticyclones is characterized by a filament of negative relative vorticity surrounded by two filaments of positive relative vorticity in both ζ and ζτ (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c, black polygon). The relationship between ζ and ζτ is corroborated by the scatterplots in Extended Data Fig. 4, confirming the existence of a SQG regime and the fact that τ can be interpreted in terms of tropopause height anomalies, with H0 the typical depth scale. In addition, the good match between ζ and ζτ confirms the positive correlation between anticyclonic vorticity and positive cloud thickness anomaly (equation (10)). Finally, an estimation of the convective APE (CAPE)34,35 within NH3 clouds leads to an order of magnitude similar to our APE, confirming its convective origin (Methods).

Convection within clouds is known to be associated with updraughts, producing positive divergence and anticyclonic vorticity at the cloud top32,36. This is consistent with our dynamical analysis, which implies that thick clouds (that is, positive optical depth anomaly τ) are associated with anticyclonic vorticity and the fact that ζτ is negatively correlated with χ (Extended Data Fig. 5). Furthermore, χ has the same magnitude as the divergence estimated from CAPE within clouds (Methods) and as the ones reported for cloud convection in Jupiter35,37. Taken together, this indicates that thick clouds are associated with positive divergence and anticyclonic vorticity, consistent with a convective origin. To double check this result, we also investigate the direct relation between τ and χ (Extended Data Figs. 3a,d and 6), which confirms the positive correlation between cloud thickness and divergence, lending further support to moist convection at Jovian high latitudes. Moist convection is most significant at 100 km scales, as suggested by the maxima of the ζτ, ζ and χ spectra (Fig. 3b).

KE and APE spectra differ greatly for scales larger than 1,600 km (Fig. 3a). The APE spectrum (Fig. 3a, orange curve) has a shallower slope and a much smaller variance than the KE spectrum (Fig. 3a, blue curve). In addition, the divergence is weak in this range (Fig. 3b). Taken together, this implies that vortices in the k−3 scale range are not directly impacted by clouds (Dynamics in the k−3 scale range section), consistent with a character and generation mechanism independent of tropopause-level forcing2. A natural follow-up question is: Can moist convection, through vortices in the k−4/3 scale range, account for the emergence and persistence of the large cyclones present at Jovian high latitudes in the k−3 scale range? This is addressed in the next section.

Upscale energy transfer

Here, we diagnose the KE transfer across scales to understand how small-scale moist convection impacts the large cyclones. The KE transfer, KEadv, is derived from the momentum equations and computed from the wind measurements (Methods). A negative (positive) value of KEadv(k) indicates a KE loss (gain) at the wavenumber k. Figure 4a reveals that scales smaller than 215 km, where the KE source due to convection is the most significant, lose KE. On the other hand, larger scales up to about 5,000 km gain KE. This indicates an upscale KE transfer in both the k−3 and k−4/3 scale ranges, from the smallest observable vortices (<100 km) up to the large cyclones (~5,000 km). Note that, while the zero-crossing value of 215 km (Fig. 4a) is weakly sensitive to the data processing and can vary between 100 and 400 km (Extended Data Fig. 7f), the upscale energy transfer up to the large cyclones’ scale is a robust feature of the flow. In addition, a downscale enstrophy (that is, the relative vorticity squared) transfer is observed at all scales (Fig. 4b), consistent with an upscale energy transfer in the classical theory of rotating turbulence38. Taken together, these results show that turbulence at Jovian high latitudes is forced by convection at 100 km scales and that the resulting KE cascades upscale to the large circumpolar and polar cyclones. This upscale KE transfer is consistent with previous analyses of Jovian mid-latitudes for scales larger than ~1,600 km (ref. 29) but has never been reported at smaller scales.

a, KE transfer in variance-preserving form (k KEadv). Positive (negative) k KEadv indicates an energy gain (loss). Scales smaller (larger) than 215 km lose (gain) energy, corresponding to an upscale energy transfer. b, Enstrophy spectral flux (ΠENS, Methods) showing a ubiquitous direct cascade from large to small scales, consistent with an upscale KE transfer in classical theory of rotating turbulence38. The thin horizontal dashed lines indicate the zero level.

Our findings are remarkably consistent with recent idealized studies of rapidly rotating Rayleigh–Bénard convection19,20,21,21,22,23,24, as well as with laboratory experiments25 and numerical simulations of forced turbulence in a rotating frame39 with generic small-scale forcing. All these studies reveal the existence of KE and APE spectra similar to those in Fig. 3a as well as an upscale KE transfer from small-scale forcing up to the large 2D vortices. They further indicate that the upscale KE transfer is enhanced by a positive feedback loop whereby large-scale vortices organize intermediate and small-scale convective features. In other words, 2D vortices organize 3D vortices and filaments, themselves constraining the convection21. The noticeable spiral bands of relative vorticity and clouds around the polar vortex (Fig. 2a,c), as well as the aggregation of thick clouds within intermediate-scale anticyclones (Extended Data Fig. 4), is consistent with such a positive feedback loop. For instance, the streamer of negative vorticity and thick clouds (Fig. 2a,c and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b) suggests that small-scale moist convection is organized by intermediate-scale vortices and filaments, with the latter being advected and stretched by the large cyclones. However, verifying these results in Jupiter would require a longer time series of observations than currently available.

Discussion

Our results show that moist convection at 100 km scales is associated with an upscale energy transfer strengthening the large cyclones at Jovian high latitudes. This energy route is expected to increase the heat transfer between deep and hot interior layers and colder upper layers, where heat gets converted into KE20,22,23,40, which is also consistent with deep convection and a deep extent of the large cyclones2,41,42. If this was the case, the presence of two convective regimes (a deep one responsible for the large cyclones and mostly forced from below, and a shallower one responsible for the smaller circulations and directly linked to clouds and winds) would point to an explicit stratification in the upper portion of Jupiter’s polar atmosphere. Other non-mutually exclusive mechanisms can also account for the genesis and persistence of the cluster of cyclones at Jupiter’s poles. Cyclones are expected in the polar regions because of the β effect, which forces cyclones (anticyclones) to drift polewards (equatorwards)43. An estimation of the β drift, or planetary Burger number8, agrees with a regime comprising multiple circumpolar cyclones9,10 (Methods). The stability of Jupiter’s cluster of cyclones may also be explained by more complex vorticity dynamics4,44,45.

This study contributes to our fundamental understanding of vortex dynamics and highlights a regime that has never been observed on another planet before. The closest dynamical analogues in the solar system may well be some parts of the Earth’s atmosphere26,28. Indeed, in close agreement with the Jovian wind measurements presented here, wind observations taken along a Lagrangian trajectory at the Earth’s tropopause display a conspicuous KE spectrum with a k−3 slope for large scales and k−5/3 for smaller scales26,46. The corresponding dynamical regime remains an open question27,46,47, mainly because of the lack of 2D observations. While a theoretical paper invokes the impact of internal waves47, recent numerical studies argue that moist convection is the leading mechanism28,46,48. The results of the present study highlight the power of combining high-resolution 2D cloud observations with wind measurements, which, if applied to the Earth’s atmosphere, should help us better understand the dynamics of our own planet.

Methods

Datasets

Infrared images

Infrared images are taken by JIRAM’s imaging channel in the M band, which operates at 4.8 μm wavelength. These are images of ammonia clouds shielding the thermal emission of the planet at different viewing angles2. During the perijove 4 orbit, JIRAM performed a series of overlapping observations of the poles of Jupiter in the hours bracketing perijove. In this paper, we consider only the north polar sequences because they provide better overlap among the images and shorter intervals between images than at the south pole (Extended Data Table 1). Observations were taken on 2 February 2017 and have a resolution of ~10 km per pixel, depending on foreshortening and spacecraft motion. The image processing, from the raw data to the polar orthographic projected maps, is thoroughly described in ref. 4. However, briefly, the first step in the processing is to determine the precise location of each pixel on the planet. This is done with Navigation and Ancillary Information Facility/Spacecraft Planet Instrument C-matrix Event (NAIF/SPICE) data from the spacecraft and precise geometric calibration of the JIRAM instrument49. The second step is to map the brightness patterns onto a 10-km gridded reference plane tangent to the planet at the pole. Mosaics are then assembled by combining 12 such infrared images separated by 30 s each. A total of four mosaics (that is, 48 infrared images, see Extended Data Table 1) are analysed, all yielding same results (Extended Data Figs. 8and 9). The projected infrared images are provided in the Supplementary Data under the filename ‘mapped brightness’. In Main, we show the results for one typical mosaic (n02, Fig. 2a), taken at mid-time between the two mosaics used to derive the wind field described below.

Wind measurements

Horizontal winds are computed by tracking cloud features between two overlapping infrared observations separated by 16 min using Tracker 3 software from JPL4 with a resolution of 10 km and an error of 2.1 m s−1. That dataset has filename ‘velocity vector’ in the Supplementary Data. To remove remaining small-scale noise, we apply a Butterworth filter of order 1 with a cutoff wavelength of 250 km. We analyse a total of two wind mosaics (derived from a total of 48 infrared images), yielding similar results (Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9). In Main, we show results for the area with broader coverage (Extended Data Fig. 1), using the mosaics n01 and n03. Note that using velocity vectors and infrared brightness maps projected onto a 15 km per pixel grid as done in ref. 4 yields similar results. An analysis of the error propagation indicates that the errors associated with the wind measurements are confined to scales less than ~50 km (Extended Data Fig. 7a–e) and therefore do not impact the conclusions of our study.

Optical depth

JIRAM infrared brightness I is primarily governed by cloud opacity50, with high I corresponding to thin clouds located at pressures of 1–5 bar (that is, within warm regions at depth), and low I corresponding to thick clouds that can reach the tropopause at a pressure of about 0.3 bar (that is, within colder upper regions)3,51,52. Thus, JIRAM observations are not taken along a constant-pressure surface and cannot be directly converted into a potential temperature from which one can infer horizontal motions at the tropopause, as done by ref. 15 for the Earth. Consequently, instead of directly using I, we use the optical depth, a proxy of cloud thickness3,13. The optical depth is computed as τa = log(I0/I), with I0 = 0.55946 W m−2 the maximum brightness measured in the infrared mosaic n02 displayed in Fig. 2a, following refs 3,13. In this study, we define the optical depth anomaly τ as \(\tau ={\tau }_{\mathrm{a}}-\overline{{\tau }_{\mathrm{a}}}\), with an overbar denoting the domain average.

Spectral methods

In this paper, all the computations are done in spectral space, which allow us to easily and accurately isolate different scale ranges53. Before taking the Fourier transform of any given variable, we apply two steps. First, we make the variable doubly periodic by applying a mirror symmetry in the x and y directions. Performing spectral analyses in a doubly periodic domain considerably improves the result’s accuracy compared with windowing methods, which damp both the large and small scales and can change the amplitude and slope of a power spectra density54. Second, the variable is detrended by subtracting the mean value.

Wavenumber spectrum

For a given doubly periodic and detrended variable ϕ, we first compute a discrete 2D fast Fourier transform \(\widehat{\phi }({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\), with kx and ky the wavenumbers in the x and y direction, then compute a 1D spectral density \(| \widehat{\phi }(k){| }^{2}\) from the 2D spectrum, with k the isotropic wavenumber defined as \(k=\sqrt{{k}_{x}^{2}+{k}_{y}^{2}}\), following a standard procedure described in ref. 55.

Butterworth filter

Throughout the paper, we apply a low-pass Butterworth filter to the wind measurements to remove the remaining small-scale noise. After experimenting, we find that a filter of order 1 with a cutoff wavenumber of 250 km produces the best results in terms of the signal-to-noise ratio. We use the spectral characteristics of τ to infer the upper bound of the spectral variance at the smallest scales. To do so, \(\hat{\zeta }\) does not exceed \(\hat{{\zeta }_{\tau }}\) (defined below) for scales smaller than 100 km where most of the wind measurements’ noise associated with taking the temporal derivative between two infrared observations is located. Note that we applied a Butterworth filter of order 2 and cutoff wavenumber of 500 km to the wind field in Extended Data Fig. 1a for visualization purposes.

Band-pass filter

A band-pass filter is implemented in spectral space and retains a range of length scales by setting the wavenumbers outside of this range to zero. In Extended Data Figs. 3–6, we apply a band-pass filter that retains length scales between 250 and 1,600 km (that is, wavenumbers between 6 × 10−4 cpkm and 4 × 10−3 cpkm). A sensitivity analysis on these wavenumbers was performed and results remain unchanged when scales smaller than 250 km are included (not shown). In Fig. 2, we apply a low-pass (b) and high-pass (c) version of this filter with a cutoff at 6 × 10−4 cpkm (that is, at the spectral slope discontinuity shown in Fig. 3ab).

Relative vorticity and horizontal divergence

Relative vorticity \(\hat{\zeta }\) and horizontal divergence \(\hat{\chi }\) are computed in spectral space from horizontal wind measurements \(\hat{u}\) and \(\hat{v}\) as

with i2 = −1. Note that the physical fields ζ and χ shown in Extended Data Fig. 1b,c are retrieved from the inverse 2D fast Fourier transform of \(\hat{\zeta }\) and \(\hat{\chi }\), respectively. In addition, the computation of ζ = vx − uy and the horizontal divergence χ = ux + vy, with subscripts denoting partial derivative, is done in physical space in ref. 4 and yields comparable results.

Rossby number

Taking the divergence of the momentum equations and assuming that the divergence’s time derivative and friction terms are negligible at leading order leads to31

with ∇h is the horizontal gradient operator, Δh is the horizontal Laplacian operator, uh is the horizontal velocity vector and P is the pressure. The Rossby number, defined as Ro \(\equiv \frac{U}{fL}\), with U and L respectively a velocity and length scale31, quantifies in equation (1) the relative importance of the Coriolis term (that is, fζ) compared with the nonlinear term. A dimensional analysis of equation (1) indicates that there is a balance between the Coriolis and pressure terms for Ro ≪ 1, called the geostrophic balance. For Ro ~ 1, the balance also involves the nonlinear terms, called the gradient wind balance. In this study, we estimate the Rossby number as Ro = ζ/f. The vortices at Jovian high latitudes have Ro ~ 1, indicating that nonlinear terms and therefore nonlinear vortex interactions are significant.

Available potential energy

Tropopause height anomalies, h, are related to the optical depth anomaly, τ, via h = H0τ, with H0 a scale depth of tropopause height anomalies. In the atmosphere, APE is defined as15,31\({\left(g\frac{{{\Theta }}}{{{{\Theta }}}_{0}}\right)}^{2}\frac{1}{{N}^{2}}\), with g the gravitational constant, Θ the potential temperature taken on a constant-pressure surface, Θ0 the reference potential temperature and N2 the squared Brunt–Väissälä frequency defined as \(g\frac{\overline{{{{\Theta }}}_{z}}}{{{{\Theta }}}_{0}}\). As the potential temperature is unknown (Optical depth section), we use a first-order Taylor series expansion \(g\frac{{{\Theta }}}{{{{\Theta }}}_{0}} \sim {N}^{2}h\), yielding

τ is thus related to the APE via h = H0τ, with H0 = 9 km and N = 4 × 10−3 s−1 chosen such that KE and APE spectra are equal in the k−4/3 scale range. N has been chosen from ref. 33, yielding a value of H0 = 9 km. Using these values yields APE = 1,296 m2 s−2. Note that N might be slightly different at the pole, which in turn would change H0, without however affecting our computations.

We suggest interpreting APE in terms of CAPE34 in order to assign moist convection to condensation process within clouds35. CAPE = \(gZ\frac{{\mathrm{\delta}} T}{ < T > }\), with δT the temperature difference between heated parcels and their background, Z the vertical length scale of the path followed by ascending parcels and <T> the background mean temperature34,35. We use the values provided by ref. 35 for NH3 clouds: <T> = 130 K at 0.5 bar, Z = 40 km (from 0.1 to 1 bar) and δT = 0.3 K. This leads to CAPE = 2,612 m2 s−2, a value close to our APE estimate. Note that the values for H2O clouds yield a CAPE magnitude ten times larger. As such, our CAPE estimation validates equation (2) and confirms that APE has a convective origin within NH3 clouds.

In addition, using the relation CAPE = \({w}_{\mathrm{max}}^{2}/2\) and Z = 40 km (ref. 35) yields an upper bound for the divergence within clouds of wmax/Z ~ 7 × 10−4 s−1. This divergence value is consistent with χ estimated from the wind measurements as well as with modelling results35,37.

Note that, if we define a stream function ψ = fP, with P the pressure (as done in the next section), the hydrostatic approximation yields \(\frac{\partial \psi }{\partial z}=\frac{g}{f}\frac{{{\Theta }}}{{{{\Theta }}}_{0}}\). APE can then be written as

The quasi-geostrophic framework

The quasi-geostrophic (QG) framework is useful to study the dynamics of a flow field of Ro ~ O(1) despite relying on a small Ro approximation31. In particular, this framework has been successfully used to study thermal convection in the limit of rapid rotation21, reminiscent of the observations presented here. In the QG framework, potential vorticity (PV) is conserved along a Lagrangian trajectory and the PV anomaly is given by

with ψ the stream function, Δ the horizontal Laplacian operator and f and N assumed constant. The relative vorticity ζ is given by Δψ. From PV conservation, ζ is related to the stretching term, \(\frac{{f}^{2}}{{N}^{2}}\frac{{\partial }^{2}\psi }{\partial {z}^{2}}\), via the horizontal divergence as31,56

with χ the horizontal divergence.

Dynamics in the k −4/3 scale range

In the k−4/3 scale range, KE and APE spectra are equal, which is equivalent to PV = 0 (refs. 14,18). This configuration corresponds to a subset category of the QG framework, referred to as surface quasi-geostrophy (SQG)14,15,16,18 and initially used in ref. 15 to study the dynamics at the Earth’s tropopause. Using equations (2) and (3), the stream function at the tropopause (where z = 0) can be written as

with subscript ‘T’ denoting the tropopause. Integration of PV = 0 (equation (4), valid in the troposphere) using the boundary condition at the tropopause given by equation (7) and assuming that ψ vanishes at z = − ∞ leads to the spectral solution

From PV = 0 and equations (7), (8) and (9), the relative vorticity at the tropopause can now be linked to the optical depth anomaly τ as

The SQG framework also allows to infer the aspect ratio between horizontal and vertical scales. Indeed, equation (8) leads to an e-folding vertical scale given by \(k\frac{N}{f}H \sim 1\), with H the depth scale. This indicates that the aspect ratio L/H of a structure is close to N/f ~ 10. In other words, the largest vortices in the k−4/3 scale range (~1,600 km) have a depth extension of about 160 km, further highlighting their shallow depth extension and therefore their 3D character.

The value of 1,600 km can be interpreted as an upper bound for the size of the baroclinic eddies, which positively depends on the convection’s strength19,21,28. Indeed, a stronger convection tends to increase the baroclinic spectrum’s amplitude (k−4/3 slope) but does not change the barotropic spectrum’s amplitude (k−3 slope) for the small scales21,28.

Dynamics in the k −3 scale range

On the one hand, APE is associated with the stretching term in the PV expression and is therefore related to the depth dependence of the stream function, or what is called the baroclinic mode57. On the other hand, KE is associated with the relative vorticity in the PV expression57. The exchanges between both energies are driven by the divergence (equations (5) and (6)). The APE spectrum in the k−3 scale range has a much smaller variance than KE (Fig. 3a), and in addition, the divergence is small (Fig. 3b) in this range. These two characteristics indicate that the depth-dependent contribution to (or the baroclinic part of) the total stream function is small and therefore that the stream function is dominated by the depth-independent part (or the barotropic part)58. These arguments imply that vortices are 2D (depth independent) in this scale range.

KE and enstrophy transfer

We diagnose the KE and enstrophy (ENS) transfer between wavenumbers in spectral space using the momentum equations at the tropopause (where vertical velocities are null). Multiplying these equations by the conjugate of the horizontal wind speed and without considering dissipation for simplicity’s sake leads to38,46,59

with asterisk indicates the complex conjugate and \({{{\rm{Re}}}}(\cdot)\) the real part. Equations (11) and (12) are the equations for the time evolution for a given wavenumber k of the KE and ENS, respectively. The first terms on the right-hand side of equations (11) and (12) are nonlinear advection terms, whereas the seconds terms are sources and/or sinks.

More precisely, the terms in equations (13) and (14) represent the KE and ENS, respectively, gained (lost) by a wavenumber k from (to) other wavenumbers. Figure 4a, from which the upscale KE transfer is inferred, shows equation (13) in a variance-preserving form (that is, multiplied by k).

Figure 4b shows the enstrophy spectral flux estimated as

with k the isotropic wavenumber defined previously.

Planetary Burger number

Here, we explore how our results compare with previous modelling studies8,9,10,11, which computed a planetary Burger number Bu = \({L}_{\mathrm{d}}^{2}/2{a}^{2}\), with Ld an internal Rossby radius of deformation and a the planetary radius. Using an upper limit value of Ld = 1,600 km (that is, the size of the largest baroclinic eddies) yields Bu = 2.6 × 10−4, corresponding to a regime with multiple circumpolar cyclones9,10 and hence comparing favourably with refs 8,9,10,11.

Data availability

JIRAM data are available at the Planetary Data System (PDS) online (https://atmos.nmsu.edu/PDS/data/PDS4/juno_jiram_bundle/data_calibrated/). Data products used in this study include calibrated, geometrically controlled, radiance data mapped onto an orthographic projection centred on the north pole and velocity vectors derived from the radiance data. The raw data used in this study are listed in the Extended Data Table 1. Brightness maps and velocity vectors can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Code availability

The code is available at https://github.com/liasiegelman/JIRAM_paper_code.

References

Adriani, A. et al. Clusters of cyclones encircling Jupiter’s poles. Nature 555, 216–219 (2018).

Mura, A. et al. Oscillations and stability of the Jupiter polar cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. e2021GL094235 (2021).

Adriani, A. et al. Two-year observations of the Jupiter polar regions by JIRAM on board Juno. J. Geophys. Res. Planets e2019JE006098 (2020).

Ingersoll, A. et al. Polygonal patterns of cyclones on Jupiter: convective forcing and anticyclonic shielding. Research Square https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-388198/v1 (preprint).

Baines, K. H. et al. Polar lightning and decadal-scale cloud variability on Jupiter. Science 318, 226–229 (2007).

Brown, S. et al. Prevalent lightning sferics at 600 megahertz near Jupiter’s poles. Nature 558, 87–90 (2018).

Becker, H. N. et al. Small lightning flashes from shallow electrical storms on Jupiter. Nature 584, 55–58 (2020).

O’Neill, M. E., Emanuel, K. A. & Flierl, G. R. Polar vortex formation in giant-planet atmospheres due to moist convection. Nat. Geosci. 8, 523–526 (2015).

O’Neill, M. E., Emanuel, K. A. & Flierl, G. R. Weak jets and strong cyclones: shallow-water modeling of giant planet polar caps. J. Atmos. Sci. 73, 1841–1855 (2016).

Brueshaber, S. R., Sayanagi, K. M. & Dowling, T. E. Dynamical regimes of giant planet polar vortices. Icarus 323, 46–61 (2019).

Brueshaber, S. R. & Sayanagi, K. M. Effects of forcing scale and intensity on the emergence and maintenance of polar vortices on Saturn and ice giants. Icarus 361, 114386 (2021).

Grassi, D. et al. First estimate of wind fields in the Jupiter polar regions from JIRAM-Juno images. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 123, 1511–1524 (2018).

Moriconi, M. et al. Turbulence power spectra in regions surrounding Jupiter’s south polar cyclones from Juno/JIRAM. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, e2019JE006096 (2020).

Blumen, W. Uniform potential vorticity flow: part I. theory of wave interactions and two-dimensional turbulence. J. Atmos. Sci. 35, 774–783 (1978).

Juckes, M. Quasigeostrophic dynamics of the tropopause. J. Atmos. Sci. 51, 2756–2768 (1994).

Held, I. M., Pierrehumbert, R. T., Garner, S. T. & Swanson, K. L. Surface quasi-geostrophic dynamics. J. Fluid Mech. 282, 1–20 (1995).

Hakim, G. J., Snyder, C. & Muraki, D. J. A new surface model for cyclone–anticyclone asymmetry. J. Atmos. Sci. 59, 2405–2420 (2002).

Lapeyre, G. Surface quasi-geostrophy. Fluids 2, 7 (2017).

Julien, K., Rubio, A. M., Grooms, I. & Knobloch, E. Statistical and physical balances in low rossby number Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 106, 392–428 (2012).

Favier, B., Silvers, L. & Proctor, M. Inverse cascade and symmetry breaking in rapidly rotating Boussinesq convection. Phys. Fluids 26, 096605 (2014).

Rubio, A. M., Julien, K., Knobloch, E. & Weiss, J. B. Upscale energy transfer in three-dimensional rapidly rotating turbulent convection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 144501 (2014).

Guervilly, C., Hughes, D. & Jones, C. Large-scale vortices in rapidly rotating Rayleigh–Bénard convection. J. Fluid Mech. 758, 407 – 435 (2014).

Guervilly, C., Hughes, D. W. & Jones, C. A. Large-scale-vortex dynamos in planar rotating convection. J. Fluid Mech. 815, 333–360 (2017).

Novi, L., von Hardenberg, J., Hughes, D. W., Provenzale, A. & Spiegel, E. A. Rapidly rotating Rayleigh–Bénard convection with a tilted axis. Phys. Rev. E 99, 053116 (2019).

Xia, H., Byrne, D., Falkovich, G. & Shats, M. Upscale energy transfer in thick turbulent fluid layers. Nat. Phys. 7, 321–324 (2011).

Nastrom, G. & Gage, K. S. A climatology of atmospheric wavenumber spectra of wind and temperature observed by commercial aircraft. J. Atmos. Sci. 42, 950–960 (1985).

Tulloch, R. & Smith, K. A theory for the atmospheric energy spectrum: depth-limited temperature anomalies at the tropopause. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14690–14694 (2006).

Waite, M. L. & Snyder, C. Mesoscale energy spectra of moist baroclinic waves. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 1242–1256 (2013).

Young, R. M. & Read, P. L. Forward and inverse kinetic energy cascades in Jupiter’s turbulent weather layer. Nat. Phys. 13, 1135–1140 (2017).

Charney, J. G. Geostrophic turbulence. J. Atmos. Sci. 28, 1087–1095 (1971).

Vallis, G. K. Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

Bony, S. et al. Clouds, circulation and climate sensitivity. Nat. Geosci. 8, 261–268 (2015).

Achterberg, R. K. & Ingersoll, A. P. A normal-mode approach to Jovian atmospheric dynamics. J. Atmos. Sci. 46, 2448–2462 (1989).

Holton, J. R. An introduction to dynamic meteorology, vol. 88 of International Geophysics Series (Elsevier Academic, 2004).

Iñurrigarro, P. et al. Observations and numerical modelling of a convective disturbance in a large-scale cyclone in Jupiter’s south temperate belt. Icarus 336, 113475 (2020).

Ingersoll, A., Gierasch, P., Banfield, D., Vasavada, A. & Team, G. I. Moist convection as an energy source for the large-scale motions in Jupiter’s atmosphere. Nature 403, 630–632 (2000).

Hueso, R. & Sánchez-Lavega, A. A three-dimensional model of moist convection for the giant planets: the Jupiter case. Icarus 151, 257–274 (2001).

Rhines, P. B. Waves and turbulence on a beta-plane. J. Fluid Mech. 69, 417–443 (1975).

Smith, L. M. & Waleffe, F. Transfer of energy to two-dimensional large scales in forced, rotating three-dimensional turbulence. Phys. Fluids 11, 1608–1622 (1999).

Boffetta, G., Mazzino, A. & Musacchio, S. Rotating Rayleigh–Taylor turbulence. Phys. Rev. Fluids 1, 054405 (2016).

Yadav, R. K., Heimpel, M. & Bloxham, J. Deep convection-driven vortex formation on Jupiter and Saturn. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb9298 (2020).

Yadav, R. K. & Bloxham, J. Deep rotating convection generates the polar hexagon on Saturn. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 13991–13996 (2020).

Theiss, J. Equatorward energy cascade, critical latitude, and the predominance of cyclonic vortices in geostrophic turbulence. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 34, 1663–1678 (2004).

Gavriel, N. & Kaspi, Y. The number and location of jupiter’s circumpolar cyclones explained by vorticity dynamics. Nat. Geosci. 14, 559–563 (2021).

Li, C., Ingersoll, A. P., Klipfel, A. P. & Brettle, H. Modeling the stability of polygonal patterns of vortices at the poles of Jupiter as revealed by the Juno spacecraft. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24082–24087 (2020).

Burgess, B. H., Erler, A. R. & Shepherd, T. G. The troposphere-to-stratosphere transition in kinetic energy spectra and nonlinear spectral fluxes as seen in ECMWF analyses. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 669–687 (2013).

Lindborg, E. The energy cascade in a strongly stratified fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 550, 207–242 (2006).

Hamilton, K., Takahashi, Y. O. & Ohfuchi, W. Mesoscale spectrum of atmospheric motions investigated in a very fine resolution global general circulation model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, 110–129 (2008).

Adriani, A. et al. JIRAM, the Jovian infrared auroral mapper. Space Sci. Rev. 213, 393–446 (2017).

Grassi, D. et al. Analysis of IR-bright regions of Jupiter in JIRAM-Juno data: methods and validation of algorithms. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 202, 200–209 (2017).

Gierasch, P. et al. Observation of moist convection in Jupiter’s atmosphere. Nature 403, 628–630 (2000).

Lindal, G. F. et al. The atmosphere of Jupiter: an analysis of the Voyager radio occultation measurements. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 86, 8721–8727 (1981).

Bender, C. M. & Orszag, S. A. Advanced Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers I: Asymptotic Methods and Perturbation Theory (Springer, 2013).

Gottlieb, D. & Orszag, S. A. Numerical Analysis of Spectral Methods: Theory and Applications (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1977).

Savage, A. C. et al. Spectral decomposition of internal gravity wave sea surface height in global models. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 7803–7821 (2017).

Hua, B. L., McWilliams, J. C. & Klein, P. Lagrangian accelerations in geostrophic turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 366, 87–108 (1998).

Pedlosky, J. Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, vol. 710 (Springer, 1987).

Smith, K. S. & Vallis, G. K. The scales and equilibration of midocean eddies: freely evolving flow. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 31, 554–571 (2001).

Frisch, U. Turbulence: The Legacy of A.N. Kolmogorov (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1995).

Acknowledgements

A portion of this work was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), grant/cooperative agreement no. 80NSSC20K0555, and a contract with the Juno mission, which is administered for NASA by the Southwest Research Institute. L.S. was first supported by a Caltech-JPL postdoctoral research grant and then by the Scripps Institutional Postdoctoral Program. P.K. acknowledges funding from JPL/NASA. A.P.I. is supported by NASA funds to the Juno project and by NSF grant number 1411952. W.R.Y. and A.B. acknowledge funding from NSF. The JIRAM project is founded by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) through ASI INAF agreements no. I/010/10/0, 2014 050 R.0, 2016-23-H.0 and 2016-23-H.1-2018. We thank A. Sánchez-Lavega and two anonymous reviewers for their comments, which helped improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. and P.K. led the data analysis and data interpretation and drafted the manuscript. S.P.E. processed the infrared brightness maps and wind vectors. A.P.I., S.P.E., W.R.Y. and A.B. contributed to the scientific interpretation of the results. A.M., A.A., D.G., C.P. and G.S. provided expertise on the JIRAM instrument. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Physics thanks Agustín Sánchez-Lavega and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Map of wind velocities, relative vorticity and horizontal divergence.

a) Map of wind velocity derived by tracking cloud motions in sequences of overlapping infrared images n01 and n03 (see Methods) after application of a Butterworth filter of order 2 and cutoff wavelength of 500 km. 1 out of 10 wind speed data point is plotted for visualization purpose. The arrow-length at the top right indicates a velocity of 50 m s−1. Note that the colorbar is saturated and maximum values reach 120 m s−1. Map of b) relative vorticity ζ and c) horizontal divergence χ corresponding to the spectra shown in Fig. 2b (blue and green curves, respectively). These fields were derived from wind measurements to which a Butterworth filter of order 1 and cutoff length scale of 250 km was applied (see Methods). The seams between the mosaic’ strips are particularly visible in c).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Histograms of Rossby number.

Histograms of Rossby number (Ro = ζ/f) for a) all length scales, b) length scales > 1,600 km (that is, wavenumbers < 6.10−4 cpkm), c) length scales < 1,600 km (that is, wavenumbers > 6.10−4 cpkm). The vertical dashed lines indicate the 0-level. The distribution skewness is indicated in each panel. Ro reaches one for scales < 1,600 km, highlighting strong nonlinear interactions (see Methods).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Band pass filtered τ, ζτ,ζ and χ between 250 and 1,600 km.

Maps of filtered a) optical depth anomaly τ, b) relative vorticity ζτ derived from τ, c) relative vorticity ζ derived from the wind measurements and d) horizontal divergence χ derived from the wind measurements after application of a band pass filter that retains length scales between 250 and 1,600 km (see Methods). The region delineated by the black polygon comprises the streamer subdomain joining two intermediate-scale anticyclones that is discussed in the main text. The blue rectangle comprises the polar vortex and the orange rectangle captures filamentary structures surrounding one of the circumpolar cyclones. These subdomains are analyzed in Extended Data Figs. 4-6.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Scatter plots between ζτ and ζ.

Scatter plots between the relative vorticity ζτ derived from τ and the relative vorticity ζ derived from the wind measurements for the fields in Extended Data Fig. 3 per subdomain: in a) the polar vortex (blue rectangle in Extended Data Fig. 3), b) the lower left filament (orange rectangle in Extended Data Fig. 3), c) the streamer subdomain (black polygon in Extended Data Fig. 3), d) the entire domain. Each point represents the average over each grid interval on the abscissa (that has a total of 200 grid intervals), and thin vertical lines show std dev around the averages. Straight lines indicate the least-square regression line between the points. The slope and r2 of the regression line are shown in each panel.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Scatter plots between ζτ and χ.

Scatter plots between the relative vorticity ζτ derived from τ and the horizontal divergence χ derived from the wind measurements for the fields in Extended Data Fig. 3 per subdomain: in a) the polar vortex (blue rectangle in Extended Data Fig. 3), b) the lower left filament (orange rectangle in Extended Data Fig. 3), c) the streamer subdomain (black polygon in Extended Data Fig. 3), d) the entire domain. Each point represents the average over each grid interval on the abscissa (that has a total of 200 grid intervals), and thin vertical lines show std dev around the averages. Straight lines indicate the least-square regression line between the points. The slope and r2 of the regression line are shown in each panel.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Scatter plots between τ and χ.

Scatter plots between the optical depth anomaly τ derived from the infrared images and the horizontal divergence χ derived from the wind measurements for the fields in Extended Data Fig. 3 per subdomain: in a) the polar vortex (blue rectangle in Extended Data Fig. 3), b) the lower left filament (orange rectangle in Extended Data Fig. 3), c) the streamer subdomain (black polygon in Extended Data Fig. 3), d) the entire domain. Each point represents the average over each grid interval on the abscissa (that has a total of 200 grid intervals), and thin vertical lines show std dev around the averages. Straight lines indicate the least-square regression line between the points. The slope and r2 of the regression line are shown in each panel.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Error propagation and sensitivity analysis.

Error propagation analysis in wind field n0103. a)-e) show the results’ envelope of 20 synthetic wind fields equal to n0103 plus an added white noise of standard deviation 2.1 m s−1, corresponding to the error of the wind measurements (see Methods). a) Power spectra density (PSD) of kinetic energy (KE). b) PSD of relative vorticity (ζ in blue), horizontal divergence (χ in green). A spectral slope discontinuity in KE and ζ occurs at 6.10−4 cpkm ( ~ 1,600 km), highlighted by the thin vertical dashed line. Thick dashed lines indicate spectral slopes obtained by curve fitting. c) χ to ζ power spectra ratio χPSD/ζPSD. The thin horizontal dashed line indicates a ratio of 1. d) KE transfer in variance preserving form (k KEadv). e) Enstrophy spectral flux (πENS, see Methods). The error is confined to scales less than ~ 50 km, as expected from the steepness of the KE spectrum and the error does not impact the KE and enstrophy transfers computation. f)-g) Sensitivity of the transfer to the data processing using wind field n0103 f) KE transfer (k KEadv). g) Enstrophy transfer (πENS). We varied the cutoff wavelength (different colors) used in the lowpass Butterworth filter of order 1. Each curve is normalized per respect to the 250 km one (blue curve, also shown in the main text) for visualization purpose. The thin horizontal dashed lines in d)-g) indicate the 0-level. The inverse KE cascade and direct enstrophy cascade is a robust feature of the flow. However, the zero-crossing is sensitive to the inclusion of small-scales.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Dynamical context from wind field n0204 and infrared mosaic n03.

Mosaic of a) optical thickness anomaly τ derived directly from the infrared mosaic n03. b) large-scale relative vorticity ζ derived from the wind measurements n0204 after application of a low-pass filter that retains length scales greater than 1,600 km and c) small-scale relative vorticity ζτ derived from τ after application of a high-pass filter that retains lengthscales smaller than 1,600 km (see Methods).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Spectral characteristics from wind field n0204 and infrared mosaic n03.

a) Power spectra density (PSD) of kinetic energy (KE, blue curve) and available potential energy (APE, orange curve). b) PSD of relative vorticity (ζ, blue curve), horizontal divergence (χ, green curve) and vorticity derived from τ (ζτ, orange curve) using wind field n0204 and infrared mosaic n03. A spectral slope discontinuity in KE and ζ occurs at 6.10−4 cpkm ( ~ 1, 600 km), highlighted by the thin vertical dashed line. Thick dashed lines show spectral slopes obtained by curve fitting. c) χ to ζ power spectra ratio χPSD/ζPSD. The thin horizontal dashed line indicates a ratio of 1. d) KE transfer in variance preserving form (k KEadv). e) Enstrophy spectral flux (πENS, see Methods). The thin horizontal dashed lines in d)-e) indicate the 0-level.

Extended Data Table 1

List of infrared images used in this study.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

README of the Supplementary Datasets.

Supplementary Data

Projected infrared images used in this study (Extended Data Table 1).

Supplementary Data

Horizontal winds used in this study derived from the mapped brightness images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siegelman, L., Klein, P., Ingersoll, A.P. et al. Moist convection drives an upscale energy transfer at Jovian high latitudes. Nat. Phys. 18, 357–361 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-021-01458-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-021-01458-y

This article is cited by

-

Quasi-two-dimensional turbulence

Reviews of Modern Plasma Physics (2023)

-

Vorticity and divergence at scales down to 200 km within and around the polar cyclones of Jupiter

Nature Astronomy (2022)

-

From storms to cyclones at Jupiter’s poles

Nature Physics (2022)