Abstract

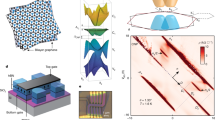

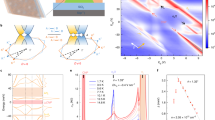

Twisted van der Waals heterostructures with flat electronic bands have recently emerged as a platform for realizing correlated and topological states with a high degree of control and tunability. In graphene-based moiré heterostructures, the correlated phase diagram and band topology depend on the number of graphene layers and the details of the external environment from the encapsulating crystals. Here, we report that the system of twisted monolayer–bilayer graphene (tMBG) hosts a variety of correlated metallic and insulating states, as well as topological magnetic states. Because of its low symmetry, the phase diagram of tMBG approximates that of twisted bilayer graphene when an applied perpendicular electric field points from the bilayer towards the monolayer graphene, or twisted double bilayer graphene when the field is reversed. In the former case, we observe correlated states that undergo an orbitally driven insulating transition above a critical perpendicular magnetic field. In the latter case, we observe the emergence of electrically tunable ferromagnetism at one-quarter filling of the conduction band, and an associated anomalous Hall effect. The direction of the magnetization can be switched by electrostatic doping at zero magnetic field. Our results establish tMBG as a tunable platform for investigating correlated and topological states.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80–84 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Yankowitz, M. et al. Tuning superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 363, 1059–1064 (2019).

Lu, X. et al. Superconductors, orbital magnets and correlated states in magic angle bilayer graphene. Nature 574, 653–657 (2019).

Codecido, E. et al. Correlated insulating and superconducting states in twisted bilayer graphene below the magic angle. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw9770 (2019).

Sharpe, A. L. et al. Emergent ferromagnetism near three-quarters filling in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 365, 605–608 (2019).

Serlin, M. et al. Intrinsic quantized anomalous Hall effect in a moiré heterostructure. Science 367, 900–903 (2020).

Saito, Y., Ge, J., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Young, A. F. Independent superconductors and correlated insulators in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 926–930 (2020).

Stepanov, P. et al. Untying the insulating and superconducting orders in magic-angle graphene. Nature 583, 375–378 (2020).

Arora, H. S. et al. Superconductivity in metallic twisted bilayer graphene stabilized by WSe2. Nature 583, 379–384 (2020).

Burg, G. W. et al. Correlated insulating states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 197702 (2019).

Shen, C. et al. Correlated states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 520–525 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Tunable correlated states and spin-polarized phases in twisted bilayer-bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 215–220 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Tunable spin-polarized correlated states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 221–225 (2020).

He, M. et al. Symmetry breaking in twisted double bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-1030-6 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Evidence of a gate-tunable Mott insulator in trilayer graphene moiré superlattice. Nat. Phys. 15, 237–241 (2019).

Chen, G. et al. Signatures of tunable superconductivity in a trilayer graphene moiré superlattice. Nature 572, 215–219 (2019).

Chen, G. et al. Tunable correlated Chern insulator and ferromagnetism in a moiré superlattice. Nature 579, 56–61 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Simulation of Hubbard model physics in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 353–358 (2020).

Regan, E. C. et al. Mott and generalized Wigner crystal states in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 359–363 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Correlated electronic phases in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 19, 861–866 (2020).

Suárez Morell, E., Pacheco, M., Chico, L. & Brey, L. Electronic properties of twisted trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 87, 125414 (2013).

Ma, Z. et al. Topological flat bands in twisted trilayer graphene. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1905.00622.pdf (2019).

Liu, J., Ma, Z., Gao, J. & Dai, X. Quantum valley Hall effect, orbital magnetism, and anomalous Hall effect in twisted multilayer graphene systems. Phys. Rev. X 9, 031021 (2019).

Zondiner, U. et al. Cascade of phase transitions and Dirac revivals in magic-angle graphene. Nature 582, 203–208 (2020).

Wong, D. et al. Cascade of electronic transitions in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 582, 198–202 (2020).

Vignolles, D. et al. Field-induced spin-density wave in (TMTSF)2NO3. Phys. Rev. B 71, 020404 (2005).

Rosenbaum, T., Field, S., Nelson, D. & Littlewood, P. Magnetic-field-induced localization transition in HgCdTe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 241–244 (1985).

Field, S., Reich, D. H., Rosenbaum, T., Littlewood, P. & Nelson, D. Electron correlation and disorder in Hg1 − xCdxTe in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 38, 1856–1864 (1988).

Young, A. F. et al. Spin and valley quantum Hall ferromagnetism in graphene. Nat. Phys. 8, 550–556 (2012).

Checkelsky, J. G., Li, L. & Ong, N. P. Divergent resistance at the Dirac point in graphene: evidence for a transition in a high magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 79, 115434 (2009).

Liu, X. et al. Tuning electron correlation in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene using coulomb screening. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2003.11072.pdf (2020).

Khalaf, E., Chatterjee, S., Bultinck, N., Zaletel, M. P. & Vishwanath, A. Charged skyrmions and topological origin of superconductivity in magic angle graphene. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.00638.pdf (2020).

Kou, X. et al. Scale-invariant quantum anomalous hall effect in magnetic topological insulators beyond the two-dimensional limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 137201 (2014).

Repellin, C., Dong, Z., Zhang, Y.-H. & Senthil, T. Ferromagnetism in narrow bands of moiré superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 187601 (2020).

Bultinck, N., Chatterjee, S. & Zaletel, M. P. Mechanism for anomalous Hall ferromagnetism in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 166601 (2020).

Zhang, Y.-H., Mao, D. & Senthil, T. Twisted bilayer graphene aligned with hexagonal boron nitride: anomalous Hall effect and a lattice model. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 033126 (2019).

Zhu, J., Su, J.-J. & MacDonald, A. H. The curious magnetic properties of orbital Chern insulators. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2001.05084.pdf (2020).

Matsukura, F., Yokura, Y. & Ohno, H. Control of magnetism by electric fields. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 209–220 (2015).

Zhang, Y.-H., Mao, D., Cao, Y., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Senthil, T. Nearly flat Chern bands in moiré superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 99, 075127 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Young, H. Polshyn, A. Millis, C.-Z. Chang, J.-H. Chu and E. Khalaf for helpful discussions. The research on correlated states in twisted monolayer–bilayer graphene was primarily supported as part of Programmable Quantum Materials, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES), under award DE-SC0019443. The measurements and understanding of ferromagnetism at the University of Washington were partially supported by NSF MRSEC 1719797. M.Y. is an Army Research Office Young Investigator (W911NF-20-1-0211). X.X. acknowledges support from the Boeing Distinguished Professorship in Physics. X.X. and M.Y. acknowledge support from the State of Washington funded Clean Energy Institute. This work made use of a dilution refrigerator system provided by NSF DMR-1725221. K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the Elemental Strategy Initiative conducted by the MEXT, Japan (grant no. JPMXP0112101001), JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. JP20H00354) and CREST (JPMJCR15F3), JST.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C., M.H. and V.H. fabricated the devices and performed the measurements. Y.-H.Z. performed the calculations. Z.F. and D.H.C. assisted with measurements in the dilution refrigerator. K.W. and T.T. grew the BN crystals. S.C., M.H., X.X., C.R.D. and M.Y. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Optical microscope images and two-terminal conductance of the tMBG devices.

(a-d), the twist angle of each device is denoted at the bottom left corner of each image. All scale bars are 5 μm. (e-f) show the two-terminal conductance measured between neighbouring pairs of contacts as indicated by the colour-coded bars in (a-b). Device D1 exhibits a small twist angle gradient of approximately 0.03° primarily along the longitudinal direction of the Hall bar. Device D2 exhibits a larger twist angle inhomogeneity of approximately 0.1°, consistent with the apparent doubling of some of the transport features in Fig. 4a of the main text.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Transport in tMBG at a variety of twist angles at T = 300 mK.

ρ as a function of n and D for (a) device D3 (θ = 1.44°), and (b) device D4 (θ = 1.55°). At these twist angles, the gap at the charge neutrality points only opens for D > 0 (pointing from monolayer to bilayer graphene). Features corresponding to single particle vHs can be seen in both conduction and valence bands. Although some features may arise owing to correlations, we do not observe any states with insulating behavior at integer ν within the bands. c-d, ρ and RH for device D1 using different contacts from Fig. 1d-e of the main text. The twist angle, θ = 1.05°, is slightly smaller than for the region of the device probed in the main text.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Energy scales and density of states of tMBG.

a, Single-particle density of states (DOS) calculated for θ = 1.08° as a function of ν and D, following the model described in the text. b, Calculated single particle gaps at ν = 0, + 4 (left axis) as a function of interlayer potential, δ. Bandwidth of the conduction band, W (right axis). The bandwidth does not vary widely over our this range of δ. c, W calculated as function of θ for δ = − 40 meV. W does not change substantially for 0.85∘ < θ < 1. 1∘. d, Experimentally measured energy gaps of ν = 0, + 2, + 4 as a function of D in device D1 (θ = 1.08∘). The single particle gaps at ν = 0, + 4 are qualitatively consistent with the predictions in b. A CI gap at ν = + 2 only emerges over a finite range of D > 0.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Transport in an in-plane magnetic field in device D1.

a, ρ as a function of ν and D at B∣∣ = 14 T. b, ρ(T) for ν = 1, 2, 3 at both B = 0 (solid curves) and B∣∣ = 14 T (dashed curves). In the former, ν = 2 exhibits insulating behavior whereas ν = 1 and 3 are metallic. In the latter, all become more resistive at low temperature, and ν = 1 and 3 begin to undergo an insulating transition at low temperature. c, Device resistance, R, versus T−1 at ν = 2 and D = + 0.39 V/nm. (Inset) Energy gaps, Δν=2, as function of B∣∣, extracted from the thermal activation measurements. Gaps are extracted by fitting the data in the main panel to \(R\propto {e}^{\Delta /2{k}_{B}T}\), where kB is the Boltzmann constant. The gap grows with larger B∣∣ suggestive of a spin-polarized ground state. However, thermal activation measurements may be complicated by additional orbital contributions owing to the multilayer structure of tMBG15.

Extended Data Fig. 5 High magnetic field transport in device D1.

a, ρ as a function of n and D for D > 0 at B⊥ = 3 T. In addition to the CI state at ν = 2, vertical blue stripes correspond to the formation of Landau levels within the symmetry broken halo region. b, ρ for D < 0 at B⊥ = 3 T. Field-assisted CI states emerge over a finite range of D, along with associated quantum oscillations. c, Energy gaps of ν = 2 and 3 at D = − 0.33 V/nm as a function of B⊥, measured by thermal activation. The gap at ν = 3 closes at high field, which may be related to the spin and valley ordering of the state, and/or competition with Landau level formation. d, ρ(T) corresponding to ν = 1, 2, 3 at B⊥ = 0 and 3.5 T. All exhibit unusual metallic temperature dependence at B = 0, but are insulating (ν = 2, 3) or near a crossover point (ν = 1) at high field.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Temperature dependence of the AHE resistivity and coercive field in device D2.

Measurements correspond to the data set shown in Fig. 4b of the main text, with ν = 0.94 and D = + 0.415 V/nm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Doping-induced switching of the magnetic order with B⊥ in device D2.

a, ρyx as ν is swept back and forth from -0.5 to +2.5 at D = + 0.415 V/nm, with B⊥= + 4 mT, + 2mT, 0mT, − 2 mT, − 4 mT. Doping-induced switching of the magnetic order is only observed within a small range of B⊥ from ~ + 2 mT to − 2 mT. At larger B⊥, the magnetic state is aligned with the applied field regardless of the sweep direction. The measurement is performed subsequent to thermally-cycling the device to T = 4 K — above the Curie temperature — and then back to base temperature. b, The difference between ρyx sweeping up and down as a function of B⊥. The red region denotes the regime in which the magnetization can be switched with doping.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Dependence of doping-induced switching on magnetic field initialization in device D2.

a-d, show hysteresis loops at ν = 0.94 and D = + 0.415 V/nm, acquired after initiating the state with different magnetic field and doping trainings. The schematics to the left of each ρyx panel denote the sequence of B⊥ and ν sweeps as a function of time. Black lines denote the initialization operations, performed prior to data acquisition. The initialized magnetic state is indicated by the starting point of the blue ρyx curve at B = 0. Subsequent to the initialization, ν is held fixed at 0.94 while B⊥ is swept back and forth. Notably, independent of the field training history, ρyx is initialized to the positive state when ν is swept down from 2.5, and to the negative state when ν is swept up from − 0.5. Subsequent magnetic field sweeping forms a similar hysteresis loop independent of the initialized state. This helps to rule out any effects of the magnetic field initialization in our observations of the doping-induced switching effect at B = 0.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Quantum oscillations in device D3 (θ = 1.44°).

a, ρxx and b, Rxy as a function of n and B⊥ at D = 0. c, Comparable Rxy map at D = − 0.2 V/nm. d, Schematic illustration of the prominent quantum oscillations observed in a. Quantum oscillations exhibit four-fold degeneracy at each value of n. For n < 0, we observe a sequence of quantum oscillations with filling factors νLL = − 2, − 6, − 10. . . . For n > 0, the sequence shifts from + 2, + 6, + 10. . . to + 4, + 8, + 12, . . . and back again as n is raised. These sequences can be understood by considering the monolayer- and bilayer-like corners of the moiré Brillouin zone as approximately uncoupled owing to the larger twist angle, in which the dominant quantum oscillations are the sum of the contributions from each band. e, Dashed blue lines denote the Landau levels of the monolayer-like bands as a function of energy, following \({E}_{LL,m}=\sqrt{2e\hslash {v}_{F}^{2}NB}\), where N is the Landau level index and vF is the Fermi velocity. Dashed red lines denote the same for the bilayer-like bands, with \({E}_{LL,b}=\frac{e\hslash B}{{m}^{* }}\sqrt{N(N-1)}\), where m* is the effective mass. The total filling factor νLL within each gap is given by the sum of the Landau level indexes for each band (solid bars). The experimentally observed sequence of quantum oscillations is well reproduced taking vF = 1.44 × 105 m/s, m* = 0.14m0, and including a charge neutrality band gap in the monolayer spectrum of ΔM = 5 meV and an offset between the monolayer and bilayer charge neutrality points of δ = 14.5 meV (indicative of band overlap). f, Similar energy diagram for D = − 0.2 V/nm. To account for the observation of νLL = − 2 at high magnetic field, a band gap for the bilayer spectrum of ΔB = 8 meV is included, and we take δ = 19.5 meV.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Quantum oscillations at D = + 0.5 V/nm in device D1 (θ = 1.08°).

Landau fan diagram up to full filling of the moiré unit cell with D = + 0.5 V/nm at T = 300 mK. Separate sequences of quantum oscillations emerge from ν = − 4 with a dominant sequence of νLL = + 4, + 8, + 12, . . . , from ν = 0 with dominant sequences of νLL = − 2, − 6, − 10, . . . and νLL = + 6, + 12, + 18, . . . , and from ν = + 2 with a dominant state at νLL = + 3. Quantum oscillations emerging from ν = + 2 with larger filling factor do not follow a simple sequence, which may be a consequence of structural disorder in the sample. These states are illustrated schematically in the bottom panel with dashed lines. Dotted lines show additional states which emerge at higher field. Gray shaded regions denote band insulators and the orange shaded region denotes the CI state. The apparent 6-fold degeneracy of electron-like quantum oscillations emerging from ν = 0 may indicate the presence of multiple Fermi surface pockets within the moiré Brillouin zone.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–6.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Data for Fig. 1b–e..

Source Data Fig. 2

Data for line plots in Fig. 2 all panels

Source Data Fig. 3

Data for Fig. 3a–d.

Source Data Fig. 4

Data for Fig. 4 all panels.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., He, M., Zhang, YH. et al. Electrically tunable correlated and topological states in twisted monolayer–bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 17, 374–380 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-01062-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-01062-6

This article is cited by

-

Vestigial singlet pairing in a fluctuating magnetic triplet superconductor and its implications for graphene superlattices

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Electric field tunable bandgap in twisted double trilayer graphene

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2024)

-

Angle-resolved transport non-reciprocity and spontaneous symmetry breaking in twisted trilayer graphene

Nature Materials (2024)

-

Mixed-dimensional moiré systems of twisted graphitic thin films

Nature (2023)

-

Orbital multiferroicity in pentalayer rhombohedral graphene

Nature (2023)