Abstract

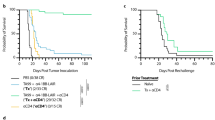

A low response rate, acquired resistance and severe side effects have limited the clinical outcomes of immune checkpoint therapy. Here, we show that combining cancer nanovaccines with an anti-PD-1 antibody (αPD-1) for immunosuppression blockade and an anti-OX40 antibody (αOX40) for effector T-cell stimulation, expansion and survival can potentiate the efficacy of melanoma therapy. Prophylactic and therapeutic combination regimens of dendritic cell-targeted mannosylated nanovaccines with αPD-1/αOX40 demonstrate a synergism that stimulates T-cell infiltration into tumours at early treatment stages. However, this treatment at the therapeutic regimen does not result in an enhanced inhibition of tumour growth compared to αPD-1/αOX40 alone and is accompanied by an increased infiltration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumours. Combining the double therapy with ibrutinib, a myeloid-derived suppressor cell inhibitor, leads to a remarkable tumour remission and prolonged survival in melanoma-bearing mice. The synergy between the mannosylated nanovaccines, ibrutinib and αPD-1/αOX40 provides essential insights to devise alternative regimens to improve the efficacy of immune checkpoint modulators in solid tumours by regulating the endogenous immune response.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Additional data and source files are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Topalian, S. L. et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 366, 2443–2454 (2012).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 711–723 (2010).

Gramaglia, I. et al. The OX40 costimulatory receptor determines the development of CD4 memory by regulating primary clonal expansion. J. Immunol. 165, 3043–3050 (2000).

Arch, R. H. & Thompson, C. B. 4-1BB and Ox40 are members of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-nerve growth factor receptor subfamily that bind TNF receptor-associated factors and activate nuclear factor kappaB. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 558–565 (1998).

Aspeslagh, S. et al. Rationale for anti-OX40 cancer immunotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 52, 50–66 (2016).

Sarff, M. et al. OX40 (CD134) expression in sentinel lymph nodes correlates with prognostic features of primary melanomas. Am. J. Surg. 195, 621–625 (2008).

Vetto, J. T. et al. Presence of the T-cell activation marker OX-40 on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and draining lymph node cells from patients with melanoma and head and neck cancers. Am. J. Surg. 174, 258–265 (1997).

Spranger, S. et al. Mechanism of tumor rejection with doublets of CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1, or IDO blockade involves restored IL-2 production and proliferation of CD8+ T cells directly within the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2, 3 (2014).

Gajewski, T. F. The next hurdle in cancer immunotherapy: overcoming the non-T-cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment. Semin. Oncol. 42, 663–671 (2015).

Minn, A. J. & Wherry, E. J. Combination cancer therapies with immune checkpoint blockade: convergence on interferon signaling. Cell 165, 272–275 (2016).

Tumeh, P. C. et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515, 568–571 (2014).

van Kooyk, Y. C-type lectins on dendritic cells: key modulators for the induction of immune responses. Biochem Soc. Trans. 36, 1478–1481 (2008).

Kodumudi, K. N., Weber, A., Sarnaik, A. A. & Pilon-Thomas, S. Blockade of myeloid-derived suppressor cells after induction of lymphopenia improves adoptive T cell therapy in a murine model of melanoma. J. Immunol. 189, 5147–5154 (2012).

Meyer, C. et al. Frequencies of circulating MDSC correlate with clinical outcome of melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 63, 247–257 (2014).

Stiff, A. et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells express Bruton’s tyrosine kinase and can be depleted in tumor-bearing hosts by ibrutinib treatment. Cancer Res. 76, 2125–2136 (2016).

Natarajan, G. et al. A Tec kinase BTK inhibitor ibrutinib promotes maturation and activation of dendritic cells. Oncoimmunology 5, e115159 (2016).

Alonso-Sande, M. et al. Development of PLGA–mannosamine nanoparticles as oral protein carriers. Biomacromolecules 14, 4046–4052 (2013).

Silva, J. M. et al. In vivo delivery of peptides and Toll-like receptor ligands by mannose-functionalized polymeric nanoparticles induces prophylactic and therapeutic anti-tumor immune responses in a melanoma model. J. Control Release 198, 91–103 (2015).

Wang, X., Ramstrom, O. & Yan, M. Dynamic light scattering as an efficient tool to study glyconanoparticle–lectin interactions. Analyst 136, 4174–4178 (2011).

De Koker, S. et al. Engineering polymer hydrogel nanoparticles for lymph node-targeted delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 1334–1339 (2016).

Azzi, J. et al. Targeted delivery of immunomodulators to lymph nodes. Cell Rep. 15, 1202–1213 (2016).

Seliger, B., Ruiz-Cabello, F. & Garrido, F. IFN inducibility of major histocompatibility antigens in tumors. Adv. Cancer Res. 101, 249–276 (2008).

Dranoff, G. et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 3539–3543 (1993).

Kowalczyk, D. W. et al. Vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells eliminate tumors by a two-staged attack. Cancer Gene Ther. 10, 870–878 (2003).

Pasare, C. & Medzhitov, R. Toll-like receptors: balancing host resistance with immune tolerance. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 677–682 (2003).

Scheller, J., Chalaris, A., Schmidt-Arras, D. & Rose-John, S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 878–888 (2011).

Fridlender, Z. G. et al. CCL2 blockade augments cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 70, 109–118 (2010).

Tsui, P. et al. Generation, characterization and biological activity of CCL2 (MCP-1/JE) and CCL12 (MCP-5) specific antibodies. Hum. Antibodies 16, 117–125 (2007).

Phan, G. Q. et al. Immunization of patients with metastatic melanoma using both class I- and class II-restricted peptides from melanoma-associated antigens. J. Immunother. 26, 349–356 (2003).

Slingluff, C. L. Jr. et al. A randomized phase II trial of multiepitope vaccination with melanoma peptides for cytotoxic T cells and helper T cells for patients with metastatic melanoma (E1602). Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 4228–4238 (2013).

Shedlock, D. J. & Shen, H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science 300, 337–339 (2003).

Gabrilovich, D. I. & Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174 (2009).

Nagaraj, S., Schrum, A. G., Cho, H. I., Celis, E. & Gabrilovich, D. I. Mechanism of T cell tolerance induced by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Immunol. 184, 3106–3116 (2010).

Sagiv-Barfi, I. et al. Therapeutic antitumor immunity by checkpoint blockade is enhanced by ibrutinib, an inhibitor of both BTK and ITK. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E966–E972 (2015).

Swart, M., Verbrugge, I. & Beltman, J. B. Combination approaches with immune-checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Front. Oncol. 6, 233 (2016).

Guo, Z. et al. PD-1 blockade and OX40 triggering synergistically protects against tumor growth in a murine model of ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE 9, e89350 (2014).

Woods, D. M., Ramakrishnan, R., Sodré, A. L., Berglund, A. & Weber, J. Abstract A067: PD-1 blockade enhances OX40 expression on regulatory T-cells and decreases suppressive function through induction of phospho-STAT3 signaling. Cancer Immunol. Res. 4, A067–A067 (2016).

Zhu, Q. et al. Using 3 TLR ligands as a combination adjuvant induces qualitative changes in T cell responses needed for antiviral protection in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 607–616 (2010).

Chen, L. & Flies, D. B. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 227–242 (2013).

Hanahan, D. & Coussens, L. M. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 21, 309–322 (2012).

Burkholder, B. et al. Tumor-induced perturbations of cytokines and immune cell networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1845, 182–201 (2014).

Fang, H. et al. TLR4 is essential for dendritic cell activation and anti-tumor T-cell response enhancement by DAMPs released from chemically stressed cancer cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 11, 150–159 (2013).

Beyersdorf, N., Kerkau, T. & Hunig, T. CD28 co-stimulation in T-cell homeostasis: a recent perspective. Immunotargets Ther. 4, 111–122 (2015).

Sagiv-Barfi, I. et al. Eradication of spontaneous malignancy by local immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaan4488 (2018).

Maher, E. A., Mietz, J., Arteaga, C. L., DePinho, R. A. & Mohla, S. Brain metastasis: opportunities in basic and translational research. Cancer Res. 69, 6015–6020 (2009).

Santarelli, J. G., Sarkissian, V., Hou, L. C., Veeravagu, A. & Tse, V. Molecular events of brain metastasis. Neurosurg. Focus 22, E1 (2007).

van den Eertwegh, A. J. et al. Combined immunotherapy with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-transduced allogeneic prostate cancer cells and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 13, 509–517 (2012).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Ipilimumab plus sargramostim vs ipilimumab alone for treatment of metastatic melanoma: a randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 312, 1744–1753 (2014).

Kaiser, A. D. et al. Towards a commercial process for the manufacture of genetically modified T cells for therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 22, 72–78 (2015).

Wilson, D. S. et al. Antigens reversibly conjugated to a polymeric glyco-adjuvant induce protective humoral and cellular immunity. Nat. Mater. 18, 175–185 (2019).

Schwartz, H. et al. Incipient melanoma brain metastases instigate astrogliosis and neuroinflammation. Cancer Res. 76, 4359–4371 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The MultiNano@MBM project was supported by The Israeli Ministry of Health and The Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia-Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (FCT-MCTES) under the framework of EuroNanoMed-II (ENMed/0051/2016 to H.F.F., R.S.-F. and S.J.). R.S.-F. thanks the European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant Agreement no. [617445]-PolyDorm and ERC Advanced Grant Agreement no. [835227] - 3DBrainStrom, The Israel Science Foundation (Grant nos. 918/14 and 1969/18), The Melanoma Research Alliance (the Saban Family Foundation–MRA Team Science Award to R.S.-F. and N.E., and Established Investigator Award to R.S.-F.) and the Israel Cancer Research Fund (ICRF). J.C., A.I.M., C.P., E.Z. and L.I.F.M. are supported by the FCT-MCTES (Fellowships SFRH/BD/87150/2012, PD/BD/113959/2015, SFRH/BD/87591/2012, SFRH/BD/78480/2011 and SFRH/BPD/94111/2013, respectively). This project has received funding from European Structural & Investment Funds through the COMPETE Programme and from National Funds through FCT under the Programme grant SAICTPAC/0019/2015 (H.F.F.). We thank E. Haimov and B. Redko from the Blavatnik Center for Drug Discovery at the Tel Aviv University for their professional and technical assistance with the peptide synthesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. and A.S. synthesized the nanovaccines and performed the in vitro and the animal studies; J.C. synthesized the man-PLGA polymers and carried out the physicochemical characterization of the nanovaccines; R.K. helped with the nanovaccine formulation; A.S., S.P. and R.K. performed the ELISPOT experiments; C.P. and A.I.M. analysed the flow cytometry experiments; E.Y. and S.P. performed the immunohistochemistry experiments; J.C. and A.I.M. carried out the tetramer assay; L.I.F.M. and E.Z. helped with the animal experiments; A.S.V. performed the AFM experiments; H.D. and N.E. contributed with the Ret cells; P.M.P.G. advised on the polymer synthesis; S.J. critically advised and contributed in interpreting the results. J.C., A.S., R.S.-F. and H.F.F. conceived and designed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote and revised the manuscript. R.S.-F. and H.F.F. were in charge of the overall direction and planning of this study, and all the authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information: Nature Nanotechnology thanks Walter Storkus and other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figs. 1–19, Supplementary Tables 1–5 and Supplementary refs.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conniot, J., Scomparin, A., Peres, C. et al. Immunization with mannosylated nanovaccines and inhibition of the immune-suppressing microenvironment sensitizes melanoma to immune checkpoint modulators. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 891–901 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0512-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0512-0

This article is cited by

-

Revolutionizing lymph node metastasis imaging: the role of drug delivery systems and future perspectives

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2024)

-

Polymer-mediated nanoformulations: a promising strategy for cancer immunotherapy

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2024)

-

Hyaluronic acid-antigens conjugates trigger potent immune response in both prophylactic and therapeutic immunization in a melanoma model

Drug Delivery and Translational Research (2023)

-

Self-adjuvanting cancer nanovaccines

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2022)

-

Nanodelivery of nucleic acids

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2022)