Abstract

Soil microorganisms globally are thought to be sustained primarily by organic carbon sources. Certain bacteria also consume inorganic energy sources such as trace gases, but they are presumed to be rare community members, except within some oligotrophic soils. Here we combined metagenomic, biogeochemical and modelling approaches to determine how soil microbial communities meet energy and carbon needs. Analysis of 40 metagenomes and 757 derived genomes indicated that over 70% of soil bacterial taxa encode enzymes to consume inorganic energy sources. Bacteria from 19 phyla encoded enzymes to use the trace gases hydrogen and carbon monoxide as supplemental electron donors for aerobic respiration. In addition, we identified a fourth phylum (Gemmatimonadota) potentially capable of aerobic methanotrophy. Consistent with the metagenomic profiling, communities within soil profiles from diverse habitats rapidly oxidized hydrogen, carbon monoxide and to a lesser extent methane below atmospheric concentrations. Thermodynamic modelling indicated that the power generated by oxidation of these three gases is sufficient to meet the maintenance needs of the bacterial cells capable of consuming them. Diverse bacteria also encode enzymes to use trace gases as electron donors to support carbon fixation. Altogether, these findings indicate that trace gas oxidation confers a major selective advantage in soil ecosystems, where availability of preferred organic substrates limits microbial growth. The observation that inorganic energy sources may sustain most soil bacteria also has broad implications for understanding atmospheric chemistry and microbial biodiversity in a changing world.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of the present study are available. All numerical data used to make figures are provided in Source Data 1 (XLSX format) and all raw phylogenetic trees are provided in Newick (NWK) format in Source Data 2 (ZIP format). All metagenomes sequenced for this project can be accessed at the Sequence Read Archive with accession number PRJNA656125 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA656125) and all MAGs are available at FigShare (https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Metagenome_Assembled_Genomes/12782543). All previously sequenced metagenomes and metatranscriptomes analysed in this study are available at NCBI BioProject with the accession numbers listed in Supplementary Table 2. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 579–590 (2017).

Bell, T., Newman, J. A., Silverman, B. W., Turner, S. L. & Lilley, A. K. The contribution of species richness and composition to bacterial services. Nature 436, 1157 (2005).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. A global atlas of the dominant bacteria found in soil. Science 359, 320–325 (2018).

Bahram, M. et al. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature 560, 233–237 (2018).

Jones, S. E. & Lennon, J. T. Dormancy contributes to the maintenance of microbial diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5881–5886 (2010).

Lennon, J. T. & Jones, S. E. Microbial seed banks: the ecological and evolutionary implications of dormancy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 119–130 (2011).

Schimel, J. & Schaeffer, S. M. Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Front. Microbiol. 3, 348 (2012).

Janssen, P. H. Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1719–1728 (2006).

Joseph, S. J., Hugenholtz, P., Sangwan, P., Osborne, C. A. & Janssen, P. H. Laboratory cultivation of widespread and previously uncultured soil bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 7210–7215 (2003).

Conrad, R. Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO). Microbiol. Rev. 60, 609–640 (1996).

Beeckman, F., Motte, H. & Beeckman, T. Nitrification in agricultural soils: impact, actors and mitigation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 50, 166–173 (2018).

Khdhiri, M. et al. Soil carbon content and relative abundance of high affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria predict atmospheric H2 soil uptake activity better than soil microbial community composition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 85, 1–9 (2015).

Ehhalt, D. H. & Rohrer, F. The tropospheric cycle of H2: a critical review. Tellus B. 61, 500–535 (2009).

Novelli, P. C., Masarie, K. A., Tans, P. P. & Lang, P. M. Recent changes in atmospheric carbon monoxide. Science 263, 1587–1590 (1994).

Novelli, P. C., Masarie, K. A. & Lang, P. M. Distributions and recent changes of carbon monoxide in the lower troposphere. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 103, 19015–19033 (1998).

Kirschke, S. et al. Three decades of global methane sources and sinks. Nat. Geosci. 6, 813–823 (2013).

Constant, P., Poissant, L. & Villemur, R. Tropospheric H2 budget and the response of its soil uptake under the changing environment. Sci. Total Environ. 407, 1809–1823 (2009).

Berney, M., Greening, C., Conrad, R., Jacobs, W. R. & Cook, G. M. An obligately aerobic soil bacterium activates fermentative hydrogen production to survive reductive stress during hypoxia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 11479–11484 (2014).

Tarr, M. A., Miller, W. L. & Zepp, R. G. Direct carbon monoxide photoproduction from plant matter. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 100, 11403–11413 (1995).

King, G. M. & Weber, C. F. Distribution, diversity and ecology of aerobic CO-oxidizing bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 107–118 (2007).

Conrad, R. The global methane cycle: recent advances in understanding the microbial processes involved. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1, 285–292 (2009).

Constant, P., Chowdhury, S. P., Pratscher, J. & Conrad, R. Streptomycetes contributing to atmospheric molecular hydrogen soil uptake are widespread and encode a putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 821–829 (2010).

Greening, C., Berney, M., Hards, K., Cook, G. M. & Conrad, R. A soil actinobacterium scavenges atmospheric H2 using two membrane-associated, oxygen-dependent [NiFe] hydrogenases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 4257–4261 (2014).

Cordero, P. R. F. et al. Atmospheric carbon monoxide oxidation is a widespread mechanism supporting microbial survival. ISME J. 13, 2868–2881 (2019).

Mörsdorf, G., Frunzke, K., Gadkari, D. & Meyer, O. Microbial growth on carbon monoxide. Biodegradation 3, 61–82 (1992).

Greening, C. et al. Genomic and metagenomic surveys of hydrogenase distribution indicate H2 is a widely utilised energy source for microbial growth and survival. ISME J. 10, 761–777 (2016).

Tveit, A. T. et al. Widespread soil bacterium that oxidizes atmospheric methane. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 8515–8524 (2019).

Islam, Z. F. et al. A widely distributed hydrogenase oxidises atmospheric H2 during bacterial growth. ISME J. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0713-4 (2020).

King, G. M. Molecular and culture-based analyses of aerobic carbon monoxide oxidizer diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 7257–7265 (2003).

Greening, C. et al. Persistence of the dominant soil phylum Acidobacteria by trace gas scavenging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10497–10502 (2015).

Berney, M. & Cook, G. M. Unique flexibility in energy metabolism allows mycobacteria to combat starvation and hypoxia. PLoS ONE 5, e8614 (2010).

Greening, C., Villas-Bôas, S. G., Robson, J. R., Berney, M. & Cook, G. M. The growth and survival of Mycobacterium smegmatis is enhanced by co-metabolism of atmospheric H2. PLoS ONE 9, e103034 (2014).

Liot, Q. & Constant, P. Breathing air to save energy – new insights into the ecophysiological role of high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase in Streptomyces avermitilis. Microbiologyopen 5, 47–59 (2016).

Greening, C., Grinter, R. & Chiri, E. Uncovering the metabolic strategies of the dormant microbial majority: towards integrative approaches. mSystems 4, e00107-19 (2019).

Khdhiri, M., Piché-Choquette, S., Tremblay, J., Tringe, S. G. & Constant, P. Meta-omics survey of [NiFe]-hydrogenase genes fails to capture drastic variations in H2-oxidation activity measured in three soils exposed to H2. Soil Biol. Biochem. 125, 239–243 (2018).

Quiza, L., Lalonde, I., Guertin, C. & Constant, P. Land-use influences the distribution and activity of high affinity CO-oxidizing bacteria associated to type I-coxL genotype in soil. Front. Microbiol. 5, 271 (2014).

Ji, M. et al. Atmospheric trace gases support primary production in Antarctic desert surface soil. Nature 552, 400–403 (2017).

Lynch, R. C., Darcy, J. L., Kane, N. C., Nemergut, D. R. & Schmidt, S. K. Metagenomic evidence for metabolism of trace atmospheric gases by high-elevation desert Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 5, 698 (2014).

King, G. M. Contributions of atmospheric CO and hydrogen uptake to microbial dynamics on recent Hawaiian volcanic deposits. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 4067–4075 (2003).

Constant, P., Chowdhury, S. P., Hesse, L., Pratscher, J. & Conrad, R. Genome data mining and soil survey for the novel Group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase to explore the diversity and ecological importance of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6027–6035 (2011).

Pandelia, M. E., Lubitz, W. & Nitschke, W. Evolution and diversification of Group 1 [NiFe] hydrogenases. Is there a phylogenetic marker for O2-tolerance? Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1817, 1565–1575 (2012).

Myers, M. R. & King, G. M. Isolation and characterization of Acidobacterium ailaaui sp. nov., a novel member of Acidobacteria subdivision 1, from a geothermally heated Hawaiian microbial mat. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66, 5328–5335 (2016).

Cunliffe, M. Correlating carbon monoxide oxidation with cox genes in the abundant marine Roseobacter clade. ISME J. 5, 685–691 (2011).

van Kessel, M. A. H. J. et al. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature 528, 555–559 (2015).

Daims, H. et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 528, 504–509 (2015).

Knief, C. Diversity and habitat preferences of cultivated and uncultivated aerobic methanotrophic bacteria evaluated based on pmoA as molecular marker. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1346 (2015).

Chiri, E. et al. Termite mounds contain soil-derived methanotroph communities kinetically adapted to elevated methane concentrations. ISME J. 14, 2715–2731 (2020).

Dunfield, P. F. et al. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 450, 879–882 (2007).

Haroon, M. F. et al. Anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to nitrate reduction in a novel archaeal lineage. Nature 500, 567–570 (2013).

Khadka, R. et al. Evolutionary history of copper membrane monooxygenases. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2493 (2018).

Van Asperen, H. et al. The role of photo-and thermal degradation for CO2 and CO fluxes in an arid ecosystem. Biogeosciences 12, 4161–4174 (2015).

Moxley, J. M. & Smith, K. A. Carbon monoxide production and emission by some Scottish soils. Tellus B. Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 50, 151–162 (1998).

Dutaur, L. & Verchot, L. V. A global inventory of the soil CH4 sink. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB4013 (2007).

McLearn, N. & Dong, Z. Microbial nature of the hydrogen-oxidizing agent in hydrogen-treated soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 35, 465–469 (2002).

King, G. M. Attributes of atmospheric carbon monoxide oxidation by Maine forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 5257–5264 (1999).

Kolb, S., Knief, C., Dunfield, P. F. & Conrad, R. Abundance and activity of uncultured methanotrophic bacteria involved in the consumption of atmospheric methane in two forest soils. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 1150–1161 (2005).

Priemé, A. & Christensen, S. Seasonal and spatial variation of methane oxidation in a Danish spruce forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 29, 1165–1172 (1997).

Chen, Q., Popa, M. E., Batenburg, A. M. & Röckmann, T. Isotopic signatures of production and uptake of H2 by soil. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 13003–13021 (2015).

DeLong, J. P., Okie, J. G., Moses, M. E., Sibly, R. M. & Brown, J. H. Shifts in metabolic scaling, production, and efficiency across major evolutionary transitions of life. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12941–12945 (2010).

Kempes, C. P. et al. Drivers of bacterial maintenance and minimal energy requirements. Front. Microbiol. 8, 31 (2017).

Marschall, E., Jogler, M., Henßge, U. & Overmann, J. Large‐scale distribution and activity patterns of an extremely low‐light‐adapted population of green sulfur bacteria in the Black Sea. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1348–1362 (2010).

Tijhuis, L., Van Loosdrecht, M. C. & Heijnen, J. J. A thermodynamically based correlation for maintenance gibbs energy requirements in aerobic and anaerobic chemotrophic growth. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 42, 509–519 (1993).

LaRowe, D. E. & Amend, J. P. Power limits for microbial life. Front. Microbiol. 6, 718 (2015).

Bradley, J. A. et al. Widespread energy limitation to life in global subseafloor sediments. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0697 (2020).

Røy, H. et al. Aerobic microbial respiration in 86-million-year-old deep-sea red clay. Science 336, 922–925 (2012).

Conrad, R. in Current Perspectives in Microbial Ecology (eds Klug, M. G. & Reddy, C. A.) 461–467 (American Society for Microbiology, 1984).

Conrad, R. Soil microorganisms oxidizing atmospheric trace gases (CH4, CO, H2, NO). Indian J. Microbiol. 39, 193–203 (1999).

Meredith, L. K. et al. Ecosystem fluxes of hydrogen in a mid‐latitude forest driven by soil microorganisms and plants. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 906–919 (2017).

Carini, P. et al. Relic DNA is abundant in soil and obscures estimates of soil microbial diversity. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16242 (2016).

Schmitz, R. A. et al. The thermoacidophilic methanotroph Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV oxidizes subatmospheric H2 with a high-affinity, membrane-associated [NiFe] hydrogenase. ISME J. 14, 1223–1232 (2020).

Islam, Z. F. et al. Two Chloroflexi classes independently evolved the ability to persist on atmospheric hydrogen and carbon monoxide. ISME J. 13, 1801–1813 (2019).

Hüppi, R. et al. Restricting the nonlinearity parameter in soil greenhouse gas flux calculation for more reliable flux estimates. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200876 (2018).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4516–4522 (2011).

Uritskiy, G. V., DiRuggiero, J. & Taylor, J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 6, 158 (2018).

Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27, 824–834 (2017).

Kang, D. D., Froula, J., Egan, R. & Wang, Z. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. Peer J 3, e1165 (2015).

Kang, D. et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. Peer J 7, e7359 (2019).

Wu, Y.-W., Simmons, B. A. & Singer, S. W. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 32, 605–607 (2015).

Olm, M. R., Brown, C. T., Brooks, B. & Banfield, J. F. dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 11, 2864–2868 (2017).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Bowers, R. M. et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 725–731 (2017).

Parks, D. H. et al. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 996–1004 (2018).

Chaumeil, P.-A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 36, 1925–1927 (2020).

Markowitz, V. M. et al. IMG: the integrated microbial genomes database and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D115–D122 (2012).

Leinonen, R., Sugawara, H. & Shumway, M., Collaboration, I. N. S. D. The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D19–D21 (2010).

Jansson, J. K. Next generation ecosystem experiment (NGEE) in the Arctic https://doi.org/10.25585/1487743 (2013).

Constant, P. Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Analysis of Soil Biogeochemical Processes Sustained by Interspecific Transfer of Molecular Hydrogen (JGI, 2014); https://doi.org/10.25585/1487738

Tiedje, J. M. Metagenomic Analysis of the Rhizosphere of Three Biofuel Crops at the KBS Intensive Site (JGI, 2013); https://doi.org/10.25585/1488010

Mohn, W. W. Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Analysis of Forest Soil Communities Across North America (JGI, 2012); https://doi.org/10.25585/1487719

Kalyuzhnaya, M. G. Systems Level Insights into Methane Cycling in Arid and Semi-Arid Ecosystems via Community Metagenomics and Metatranscriptomics (JGI, 2016); https://doi.org/10.25585/1488146

Cadillo-Quiroz, H. Microbial Composition and Metagenomic Functional Potential Across Tropical Peatlands: Comparative Evaluation and Modeling of C decomposition to Greenhouse Gases (JGI, 2015); https://doi.org/10.25585/1488117

Oliveira, R. Unravelling Microbial Communities Associated with Native Plant Species from P-Impoverished Soils of a Global Biodiversity Hotspot (JGI, 2017); https://doi.org/10.25585/1488283

Pett-Ridge, J. Microbial Carbon Transformations in Wet Tropical Soils: Effects of Redox Fluctuation (JGI, 2017); https://doi.org/10.25585/1488160

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 11, 119 (2010).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2014).

Anantharaman, K. et al. Thousands of microbial genomes shed light on interconnected biogeochemical processes in an aquifer system. Nat. Commun. 7, 13219 (2016).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Kopylova, E., Noé, L. & Touzet, H. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinform. 28, 3211–3217 (2012).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinform. 28, 3150–3152 (2012).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 (2015).

Smith, S. M. et al. Crystal structure and characterization of particulate methane monooxygenase from Methylocystis species strain M. Biochemistry 50, 10231–10240 (2011).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Helgeson, H., Kirkham, D. & Flowers, G. Theoretical prediction of the thermodynamic behavior of aqueous electrolytes by high pressures and temperatures; IV, calculation of activity coefficients, osmotic coefficients, and apparent molal and standard and relative partial molal properties to 600 d. Am. J. Sci. 281, 1249–1516 (1981).

Shock, E. L. & Helgeson, H. C. Calculation of the thermodynamic and transport properties of aqueous species at high pressures and temperatures: correlation algorithms for ionic species and equation of state predictions to 5 kb and 1000 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 52, 2009–2036 (1988).

Shock, E. L., Oelkers, E. H., Johnson, J. W., Sverjensky, D. A. & Helgeson, H. C. Calculation of the thermodynamic properties of aqueous species at high pressures and temperatures. Effective electrostatic radii, dissociation constants and standard partial molal properties to 1000 °C and 5 kbar. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 88, 803–826 (1992).

Johnson, J. W., Oelkers, E. H. & Helgeson, H. C. A software package for calculating the standard molal thermodynamic properties of minerals, gases, aqueous species and reactions from 1 to 5000 bars and 0° to 1000 °C. Comput. Geosci. 18, 899–947 (1992).

Shock, E. L., Helgeson, H. C. & Sverjensky, D. A. Calculation of the thermodynamic and transport properties of aqueous species at high pressures and temperatures: standard partial molal properties of inorganic neutral species. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 2157–2183 (1989).

Shock, E. L. & Helgeson, H. C. Calculation of the thermodynamic and transport properties of aqueous species at high pressures and temperatures: standard partial molal properties of organic species. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 915–945 (1990).

Sverjensky, D. A., Shock, E. L. & Helgeson, H. C. Prediction of the thermodynamic properties of aqueous metal complexes to 1000 °C and 5 kb. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 1359–1412 (1997).

Schulte, M. D., Shock, E. L. & Wood, R. H. The temperature dependence of the standard-state thermodynamic properties of aqueous nonelectrolytes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 3919–3930 (2001).

Amend, J. P. & LaRowe, D. E. Minireview: demystifying microbial reaction energetics. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 3539–3547 (2019).

Větrovský, T. & Baldrian, P. The variability of the 16S rRNA gene in bacterial genomes and its consequences for bacterial community analyses. PLoS ONE 8, e57923 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellowship (DE170100310; C.G.), a Discovery Project grant (DP180101762; C.G. and P.L.M.C.), a Swiss National Foundation Early Mobility Postdoctoral Fellowship (P2EZP3_178421; E.C.), a NSFC grant (41906076; X.D.), a NERC grant (NE/T010967/1; J.B.), a Humboldt Foundation Fellowship (J.B.), Monash University PhD scholarships (S.K.B. and P.M.L.), a Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment Grant (S.K.B) and an NHMRC EL2 Fellowship (APP1178715; salary for C.G.). We thank M. Chuvochina for etymological advice, J. Lloyd for field assistance and W. Whitman, S. Chown, S. Morales, M. Stott and G. Cook for formative discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.G. conceived and supervised this study. S.K.B., C.G., E.C. and P.A.N. designed experiments and analysed data. Different authors were responsible for performing fieldwork (S.K.B., E.C., P.M.L., C.G.), laboratory work (S.K.B., T.J., E.C.), metagenome assembly (X.D.), metagenome analysis (S.K.B., C.G., X.D., E.C.), phylogenetic analysis (C.G.), protein modelling (R.G.) and thermodynamic modelling (J.A.B., P.A.N., D.L., E.C., S.K.B.). S.K.A. and P.L.M.C. provided logistical and theoretical support. C.G., S.K.B. and P.A.N. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Composition of the bacterial and archaeal communities sequenced in each soil metagenome.

Stacked barcharts depicting the relative abundance of different phyla in (a) Australian soils and (b) global soils based on reads for the single-copy ribosomal protein gene rplP. Alpha diversity is shown as observed and estimated richness (Chao1) in (c) Australian soils and (d) global soils. Boxplots show median, lower and upper quartile, and minimum and maximum values. This is based on four biological replicates for the four Australian soils (n = 16) at depths of 0-5, 5-10, 15-20, and 25-30 cm, and biological triplicates for the eight global soils (n = 24). For beta diversity, abundance-based distance matrix Bray-Curtis diversity is visualized on a multidimensional PcoA plot for both Australian and global soils. Testing for significant differences in community structure between depths and ecosystems was performed using a one-way PERMANOVA with 999 permutations.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Metatranscriptomic analysis comparing metabolic marker gene expression across three global soils with paired metagenome and metatranscriptome datasets.

(a) Relative abundance of quality-filtered metatranscriptomic short reads expressed as the total reads per kilobase per million (RPKM). (b) Relative abundance of genes in each metatranscriptome mapped to the corresponding assemblies from each soil expressed as total transcripts per million (TPM).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Analysis of aerobic methane oxidation enzymes and pathways in sampled soils.

(a) Maximum-likelihood tree of amino acid sequences of particulate methane monooxygenase A subunit (PmoA), a marker for aerobic methane oxidation. The tree shows 2 sequences from soil metagenome-assembled genomes (blue) and 12 sequences from unbinned contigs (red) alongside 93 representative sequences from NCBI reference genomes (black). The tree shows the affiliation of the PmoA from Candidatus Methylotropicum kingii with those of amplicons of the tropical upland soil cluster (TUSC). Also shown are reference sequences of other members of the copper membrane monooxygenase superfamily, namely ammonia monooxygenase (AmoA), hydrocarbon monooxygenase (HmoA), and groups of unknown function (including PxmA). The tree was constructed using the JTT matrix-based model, used all sites, and was bootstrapped with 50 replicates and midpoint-rooted. Source data is provided in Newick (nwk) format. (b) Metabolic reconstruction of the putative novel methanotroph Candidatus Methylotropicum kingii. The core pathways associated with energy conservation and carbon acquisition are shown, with genes detected shown in italics. The bacterium is predicted to use methane, methanol, and acetate as energy and carbon sources. In addition, it can use molecular hydrogen as an electron donor via a group 1f [NiFe]-hydrogenase. The bacterium is predicted to use the electron acceptors oxygen via a cytochrome c oxidase and nitrous oxide via a nitrous oxide reductase. Its particulate methane monooxygenase forms a distinct phylogenetic lineage with amplicons from the Tropical Upland Soil Cluster (TUSC), whereas its methanol dehydrogenase is closely related to those in previously sequenced Gemmatimonadota MAGs inferred to be methylotrophic. The genome encodes key enzymes for the serine cycle for assimilation of one-carbon sources. Abbreviations: H4F = tetrahydrofolate; Hyd = group 1f [NiFe]-hydrogenase; pMMO = particulate methane monooxygenase; MDH = methanol dehydrogenase; PQQ = pyrroloquinoline quinone; I = NADH dehydrogenase (complex I); II = succinate dehydrogenase (complex II); IV = cytochrome aa3 oxidase (complex IV). Dashed black lines indicate diffusion. Dashed gray lines indicate unknown process or undetected genes. (c) Molecular model of the putative particulate methane monooxygenase (Pmo) from Candidatus Methylotropicum kingii and comparison with putative catalytic sites of other experimentally validated Pmos. (i) Molecular model of the functional homotrimer of the putative Pmo complex from Ca. M. kingii, shown as a cartoon representation. PmoA, PmoB, and PmoC subunits from one Pmo complex are colored in light blue, dark blue, and sky blue respectively. The other two Pmo complexes in the trimer are colored in transparent yellow. Cu ions bound in the putative active site of the colour-coded Pmo complex are shown as ochre spheres. TM = transmembrane. (ii) Zoomed view of the Pmo complex from panel A, with the three Pmo subunits labelled and the putative active sites CuB and CuC highlighted. (iii) Stick representation of residues in the CuB and CuC active sites of Pmo molecular models from Ca. M. kingii (Gemmatimonadota) and Methylacidiphilum infernorum (Verrucomicrobiota), and from the crystal structure (PDB ID: 3RGB) of Pmo from the Methylococcus capsulatus (Proteobacteria), showing that both sites are conserved between Pmo from Ca. M. kingii and M. capsulatus. Pmo from M. infernorum lacks the CuB site, suggesting this site is not responsible for methane oxidation. (iv) Sequence alignment of metal binding motifs from the CuB (left) and CuC (right) sites from Pmo from Ca. M. kingii (cMk.), M. capsulatus (Mc.), Candidatus Methylomirabilis limnetica (cMl.; Methylomirabilota), and M. infernorum (Mi.). Amino acids involved in Cu coordination are highlighted.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Biogeochemical measurements of in situ soil gas concentrations and validation of static chamber setup.

(a) Mean soil-gas profiles normalized to the respective ambient air concentration (dashed line) of four biological replicates collected at depths of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 16 cm across four Australian ecosystems (n = 112). Note that the different gases were sampled at identical depths, but points are plotted slightly offset on the y-axis for better visibility of error bars. (b) Laboratory static chamber incubations (n = 3) to control for abiotic release of trace gases from chamber’s plastic components. Chamber headspace mixing ratios of hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), and methane (CH4) were measured at eight time points during ~25 minutes of incubation time of an inert stainless steel surface. Measurement setup, sampling procedure, and sampling frequency followed those applied during the in situ chamber incubations performed to measured soil-atmosphere flux of trace gases. Circles indicate mixing ratio averaged from three independent incubations, with the vertical lines denoting one standard deviation. Dashed lines indicate the mixing ratio of trace gas averaged across three air samples.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Maximum-likelihood tree of amino acid sequences of group 3 [NiFe]-hydrogenase large subunits, a marker for hydrogen production during fermentation processes.

The tree shows 129 sequences from soil metagenome-assembled genomes (blue) alongside 172 representative sequences from NCBI reference genomes (black). The subgroup of each reference sequence is denoted according to the HydDB classification scheme40. The tree was constructed using the JTT matrix-based model, used all sites, and was bootstrapped with 50 replicates and midpoint-rooted. All sequences shorter than 350 amino acids were omitted. Source data is provided in Newick (nwk) format.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Gas chromatography studies of one ex situ trace gas consumption experiment.

Shown are four biological replicates collected at depths of 0-5, 5-10, 15-20, and 25-30 cm across four Australian ecosystems (n = 64). Depicted are the oxidation rates recorded over time of (a) atmospheric H2, (b) atmospheric CO, and (c) atmospheric CH4 by soils at each depth compared to heat-killed control soils. Oxidation of the three gases was also measured in the dryland soils following hydration, that is Dryland (wet) samples. Points show average values and vertical lines the error bars representing one standard deviations of four biological replicates. Significance testing of differences in ex situ oxidation rates between ecosystem type and soil depth was carried out using a one-sided Kruskall Wallis H test followed by a pairwise Wilcoxon tests with adjusted p-values using a Benjamini Hochberg correction for multiple testing. Boxplots show median, lower and upper quartile, and minimum and maximum values comparing the ex situ rates of H2, CO, and CH4 oxidation between depths and ecosystems for (d) cell-specific rates and (e) bulk reaction rates per gram of dry soil.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Copy number of the 16S rRNA gene per gram of soils of four biological replicates.

Soil samples were collected at depths of 0-5, 5-10, 15-20, and 25-30 cm across four Australian ecosystems, with four biological replicates for each depth (n = 64). Boxplots show median, lower and upper quartile, and minimum and maximum values.

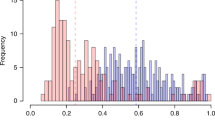

Extended Data Fig. 8 Comparison of the theoretical and measured population of trace gas oxidizers in soils.

Shown are four biological replicates collected at depths of 0-5, 5-10, 15-20, and 25-30 cm across four Australian ecosystems (n = 64). The theoretical populations, in line with the methods of Conrad68, were estimated from thermodynamic modeling and measured ex situ oxidation rates assuming a single maintenance energy for all cells. Two different values were used: 8.9 × 10-15 W cell-1 as assumed by Conrad68 and 1.9 × 10-15 W cell-1 as the median of metabolic rates reported by DeLong et al60. The measured populations of trace gas oxidizers were determined from 16S rRNA gene copy numbers and the relative abundance of the respective functional gene as determined from metagenomics. The ratio of theoretical vs. measured population is equivalent to dividing our calculated power per cell by the respective maintenance energy above. Boxplots show median, lower and upper quartile, and minimum and maximum values.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Maximum-likelihood tree of amino acid sequences of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase / oxygenase (RbcL), a marker for carbon fixation through the Calvin-Benson cycle.

The tree shows 68 sequences from soil metagenome-assembled genomes (blue) alongside 126 representative sequences from NCBI reference genomes (black). The subtype of each reference sequence is denoted. The tree was constructed using the JTT matrix-based model, used all sites, and was bootstrapped with 50 replicates and midpoint-rooted. Source data is provided in Newick (nwk) format.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Summary of the processes and mediators of trace gas cycling at the soil-atmosphere interface.

The soil bacterial phyla capable of consuming the trace gases H2 (via group 1 and 2 [NiFe]-hydrogenases), CO (via form I carbon monoxide dehydrogenases), and CH4 (via particulate methane monooxygenases) are shown. They are listed in order of the number of metagenome-assembled genomes recovered (black for highly abundant and grey for less abundant trace gas oxidizers). The downward arrows show the net consumption of atmospheric H2, CO, and CH4 by soil bacteria. The upward arrows show processes that result in endogenous production and internal cycling of trace gases. The green boxes indicate biotic processes, whereas the brown boxes indicate abiotic processes.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–12 and Figs. 1–10.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–12.

Supplementary Data

Raw phylogenetic trees in NWK format for Fig. 2a,b, Extended Data Figs. 3, 5 and 9 and Supplementary Figs. 1–10.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Numerical source data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bay, S.K., Dong, X., Bradley, J.A. et al. Trace gas oxidizers are widespread and active members of soil microbial communities. Nat Microbiol 6, 246–256 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-00811-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-00811-w

This article is cited by

-

Trace gas oxidation sustains energy needs of a thermophilic archaeon at suboptimal temperatures

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Deep subsurface igneous rocks from the Deccan traps harbor H2 and CO2 utilizing chemolithoautotrophic bacteria

Biologia (2024)

-

Characterization and environmental applications of soil biofilms: a review

Environmental Chemistry Letters (2024)

-

Nitrogen fixation and diazotroph diversity in groundwater systems

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Structural basis for bacterial energy extraction from atmospheric hydrogen

Nature (2023)