Abstract

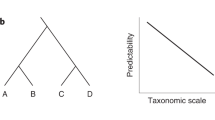

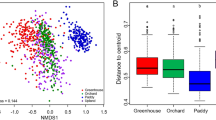

The emergence of high-throughput DNA sequencing methods provides unprecedented opportunities to further unravel bacterial biodiversity and its worldwide role from human health to ecosystem functioning. However, despite the abundance of sequencing studies, combining data from multiple individual studies to address macroecological questions of bacterial diversity remains methodically challenging and plagued with biases. Here, using a machine-learning approach that accounts for differences among studies and complex interactions among taxa, we merge 30 independent bacterial data sets comprising 1,998 soil samples from 21 countries. Whereas previous meta-analysis efforts have focused on bacterial diversity measures or abundances of major taxa, we show that disparate amplicon sequence data can be combined at the taxonomy-based level to assess bacterial community structure. We find that rarer taxa are more important for structuring soil communities than abundant taxa, and that these rarer taxa are better predictors of community structure than environmental factors, which are often confounded across studies. We conclude that combining data from independent studies can be used to explore bacterial community dynamics, identify potential ‘indicator’ taxa with an important role in structuring communities, and propose hypotheses on the factors that shape bacterial biogeography that have been overlooked in the past.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Proser, J. I. Dispersing misconceptions and identifying opportunities for the use of ‘omics’ in soil microbial ecology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 439–446 (2015).

Bardgett, R. D. & van der Putten, W. H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 515, 505–511 (2014).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 6, 1621–1624 (2012).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Fungal biogeography. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 346, 1256688 (2014).

Davison, J. et al. Fungal symbionts. Global assessment of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus diversity reveals very low endemism. Science 349, 970–973 (2015).

Wieder, W. R., Bonan, G. B. & Allison, S. D. Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 909–912 (2013).

Karhu, K. et al. Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration rates enhanced by microbial community response. Nature 513, 81–84 (2014).

Barberán, A., Casamayor, E. O. & Fierer, N. The microbial contribution to macroecology. Front. Microbiol. 5, 203 (2014).

Ramirez, K. S. et al. Biogeographic patterns in below-ground diversity in New York City’s Central Park are similar to those observed globally. P. R. Soc. B 281, 20141988 (2014).

O’Brien, S. L. et al. Spatial scale drives patterns in soil bacterial diversity. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 2039–2051 (2016).

Evans, S., Martiny, J. B. H. & Allison, S. D. Effects of dispersal and selection on stochastic assembly in microbial communities. ISME J. 11, 176–185 (2017).

Talbot, J. M. et al. Endemism and functional convergence across the North American soil mycobiome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6341–6346 (2014).

Barber, A. et al. Why are some microbes more ubiquitous than others? Predicting the habitat breadth of soil bacteria. Ecol. Lett. 17, 794–802 (2014).

Ranjard, L. et al. Turnover of soil bacterial diversity driven by wide-scale environmental heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 4, 1434 (2013).

Jetz, W., McPherson, J. M. & Guralnick, R. P. Integrating biodiversity distribution knowledge: toward a global map of life. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 151–159 (2012).

Ricketts, T. H. et al. Disaggregating the evidence linking biodiversity and ecosystem services. Nat. Commun. 7, 13106 (2016).

Dirzo, R. et al. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345, 401–406 (2014).

Patterson, D. J., Cooper, J., Kirk, P. M., Pyle, R. L. & Remsen, D. P. Names are key to the big new biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 686–691 (2010).

Santos, A. M. & Branco, M. The quality of name-based species records in databases. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 6–7 (2012).

Beiko, R. G. Microbial malaise: how can we classify the microbiome? Trends Microbiol. 23, 671–679 (2015).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Standardizing metadata and taxonomic identification in metabarcoding studies. Gigascience 4, 34 (2015).

Ramirez, K. S. et al. Toward a global platform for linking soil biodiversity data. Front. Ecol. Evol. 3, 91 (2015).

Turner, W. et al. Free and open-access satellite data are key to biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 182, 173–176 (2015).

Gilbert, J. A., Jansson, J. K. & Knight, R. The Earth Microbiome project: successes and aspirations. BMC Biol. 12, 69 (2014).

Joppa, L. N. et al. Big data and biodiversity. Filling in biodiversity threat gaps. Science 352, 416–418 (2016).

Sinha, R., Abnet, C. C., White, O., Knight, R. & Huttenhower, C. The Microbiome Quality Control project: baseline study design and future directions. Genome Biol. 16, 276 (2015).

Sogin, M. L. et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored ‘rare biosphere’. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12115–12120 (2006).

García-Palacios, P. et al. Are there links between responses of soil microbes and ecosystem functioning to elevated CO2, N deposition and warming? A global perspective. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 1590–1600 (2015).

Hermans, S. M. et al. Bacteria as emerging indicators of soil condition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e02826-16 (2016).

Philippot, L. et al. The ecological coherence of high bacterial taxonomic ranks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 523–529 (2010).

Shade, A., Caporaso, J. G., Handelsman, J., Knight, R. & Fierer, N. A meta-analysis of changes in bacterial and archaeal communities with time. ISME J. 7, 1493–1506 (2013).

Hendershot, J. N., Read, Q. D., Henning, J. A., Sanders, N. J. & Classen, A. T. Consistently inconsistent drivers of microbial diversity and abundance at macroecological scales. Ecology 98, 1757–1763 (2017).

Bier, R. L. et al. Linking microbial community structure and microbial processes: an empirical and conceptual overview. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91, fiv113 (2015).

Walters, W. A., Xu, Z. & Knight, R. Meta-analyses of human gut microbes associated with obesity and IBD. FEBS Lett. 588, 4223–4233 (2014).

Bik, H. M. et al. Sequencing our way towards understanding global eukaryotic biodiversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 233–243 (2012).

Lauber, C. L., Hamady, M., Knight, R. & Fierer, N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 5111–5120 (2009).

McDonald, D. et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 6, 610–618 (2012).

Lozupone, C. A. et al. Meta-analyses of studies of the human microbiota. Genome Res. 23, 1704–1714 (2013).

Pawluczyk, M. et al. Quantitative evaluation of bias in PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing derived from metabarcoding samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 407, 1841–1848 (2015).

Lu, X., Seuradge, B. J. & Neufeld, J. D. Biogeography of soil Thaumarchaeota in relation to soil depth and land usage. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93, fiw246 (2017).

Jung, S. P. & Kang, H. Assessment of microbial diversity bias associated with soil heterogeneity and sequencing resolution in pyrosequencing analyses. J. Microbiol. 52, 574–580 (2014).

Langille, M. G. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 814–821 (2013).

Jousset, A. et al. Where less may be more: how the rare biosphere pulls ecosystems strings. ISME J. 11, 853–862 (2017).

De Cáceres, M. & Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90, 3566–3574 (2009).

Maestre, F. T. et al. Increasing aridity reduces soil microbial diversity and abundance in global drylands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15684–15689 (2015).

Knights, D. et al. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking. Nat. Methods 8, 761–763 (2011).

Muir, P. et al. The real cost of sequencing: scaling computation to keep pace with data generation. Genome Biol. 17, 53 (2016).

Rideout, J. R. et al. Subsampled open-reference clustering creates consistent, comprehensive OTU definitions and scales to billions of sequences. PeerJ 2, e545 (2014).

Yilmaz, P. et al. The genomic standards consortium: bringing standards to life for microbial ecology. ISME J. 5, 1565–1567 (2011).

Wickham, H. & Francois, R. dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. R package v. 0.5.0 (CRAN, 2016); https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr.

The R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016); https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf.

Wilke, A. et al. The MG-RAST metagenomics database and portal in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D590–D594 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Suzuki, M. T. & Giovannoni, S. J. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification of mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 625–630 (1996).

Sipos, R. et al. Effect of primer mismatch, annealing temperature and PCR cycle number on 16S rRNA gene-targeting bacterial community analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 60, 341–350 (2007).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1 (2013).

Joshi, N. A. & Fass, J. N. Sickle: a sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files. v. 1.33 (2011); https://github.com/najoshi/sickle.

Rognes, T. et al. vsearch: VSEARCH 1.9.6. (2016); https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.44512.

McDonald, D. et al. The Biological Observation Matrix (BIOM) format or: how I learned to stop worrying and love the ome-ome. Gigascience 1, 7 (2012).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Koster, J. & Rahmann, S. Snakemake — a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics 28, 2520–2522 (2012).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Breiman, L. & Cutler, A. Using Random Forests v4.0 (UC Berkeley, 2003); https://www.scribd.com/document/208387804/Using-Random-Forests-v4-0.

Shi, T. & Horvath, S. Unsupervised learning with Random Forest predictors. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 15, 118–138 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the people who contributed data and input to this study. This study was conducted at a workshop (May 2015, Manchester, UK) funded by the British Ecological Society’s special interest group Plants-Soils-Ecosystems and organized by F.T.d.V. and K.S.R. This study and participants were funded in part by ERC Advanced Grant 26055290 (K.S.R., and W.H.v.d.P.); BBSRC David Phillips Fellowship (BB/L02456X/1) (F.T.d.V.); ERC Grant Agreements 242658 (BIOCOM) and 647038 (BIODESERT) (F.T.M.); the European Regional Development Fund (Centre of Excellence EcolChange) (J.D.); Yorkshire Agricultural Society, Nafferton Ecological Farming Group, and the Northumbria University Research Development Fund (C.H.O.); BBSRC Training Grant (BB/K501943/1) (C.H.); Wallenberg Academy Fellowship (KAW 2012.0152), Formas (214-2011-788) and Vetenskapsrådet (612-2011-5444) (E.D.); the Glastir Monitoring & Evaluation Programme (contract reference: C147/2010/11) and the full support of the GMEP team on the Glastir project (D.L.J., S.C., and D.A.R.). Computing was facilitated by the University of Manchester Condor pool and the CLIMB infrastructure (http://www.climb.ac.uk).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea for this study was conceived by F.T.d.V. and K.S.R. The data sets were compiled by C.G.K., R.G., J.D., A.H., B.C., G.F., A.L.S., and J.R. Metadata were compiled by J.D. and J.R. Raw sequence analysis was conducted by M.d.H. Primer bias analysis was conducted by A.C. Random Forest analyses and figures were conducted by C.G.K. The manuscript was written by K.S.R., C.G.K., and F.T.d.V., with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 and Supplementary Figures 1–10.

Figure Generation Data

Supplementary Table 4: Data used to generate figures.

Figure Generation Code

R code use to generate figures.

Supplementary Table 1

Summary of all datasets used.

Supplementary Table 5

Name-matched data.

Supplementary Table 6

Sequence-matched data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramirez, K.S., Knight, C.G., de Hollander, M. et al. Detecting macroecological patterns in bacterial communities across independent studies of global soils. Nat Microbiol 3, 189–196 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-017-0062-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-017-0062-x

This article is cited by

-

Heritable microbiome variation is correlated with source environment in locally adapted maize varieties

Nature Plants (2024)

-

Ecological insights into soil health according to the genomic traits and environment-wide associations of bacteria in agricultural soils

ISME Communications (2023)

-

Multidimensional specialization and generalization are pervasive in soil prokaryotes

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Above- and belowground fungal biodiversity of Populus trees on a continental scale

Nature Microbiology (2023)

-

Defending Earth’s terrestrial microbiome

Nature Microbiology (2022)