Abstract

Ferroelectrics subject to suitable electric boundary conditions present a steady negative capacitance response1,2. When the ferroelectric is in a heterostructure, this behaviour yields a voltage amplification in the other elements, which experience a potential difference larger than the one applied, holding promise for low-power electronics3. So far research has focused on verifying this effect and little is known about how to optimize it. Here, we describe an electrostatic theory of ferroelectric/dielectric superlattices, convenient model systems4,5, and show the relationship between the negative permittivity of the ferroelectric layers and the voltage amplification in the dielectric ones. Then, we run simulations of PbTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattices to reveal the factors most strongly affecting the amplification. In particular, we find that giant effects (up to tenfold increases) can be obtained when PbTiO3 is brought close to the so-called ‘incipient ferroelectric’ state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

All materials present a positive global capacitance or dielectric constant on account of thermodynamic stability. Nevertheless, local negative capacitance (NC) states can be obtained in various ways2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Most interestingly, by placing a ferroelectric in contact with a dielectric or non-ideal electrodes9,14,15, we can prevent it from reaching its ground state (homogenous polarization), forcing it into a configuration of relatively high energy. Such a frustrated ferroelectric will typically display a steady NC response upon application of an electric field2,6,7,9,10. This has been shown in detail for multidomain structures in ferroelectric/dielectric superlattices4,5,11,16,17.

To understand steady-state NC, consider the superlattice in Fig. 1, where ferroelectric (f) and dielectric (d) layers repeat periodically along the stacking direction z. In the absence of free carriers, Maxwell’s first equation dictates ∇ ⋅ D = ρfree = 0, so the z-component of the planar-averaged displacement vector is continuous. We thus have D = Df = Dd, where D is the superlattice displacement while Df and Dd are the layer vectors (z subscript omitted for simplicity). Using the definitions in Fig. 1, this yields

where ϵ0 is vacuum permittivity, P = L−1(lfPf + ldPd) is the superlattice polarization, \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\) is the external electric field along z and the total field in layer i (i = f, d) is

Further, as D = Di we have

which shows that induced fields \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ind}}}},i}\) appear when the local and global polarizations differ. For the f-layer we typically have Pf > P, so that \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ind,f}}}}}\) opposes Pf; this is the so-called ‘depolarizing field’.

The thicknesses of the ferroelectric and dielectric layers are given by lf and ld, respectively; L = lf + ld is the thickness of the repeated unit. For an arbitrary external field \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\), and in the absence of free carriers, all layers present the same vertical component of the displacement vector, so that Df = Dd. As illustrated in the figure, the displacement Di of layer i involves the layer polarization Pi, the field \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ind}}}},i}\) induced in the layer and the external field \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\).

Because of the superlattice periodicity, the total voltage associated to the induced fields is null, implying \({l}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\mathrm{nd,d}}}+{l}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ind,f}}}}}=0\). Hence, \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}{\mathrm{xt}}}\) is the only macroscopic field acting on the system.

To examine the response to a variation of the external field \({\mathrm{d}}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\), it is useful to introduce a quantity we call the ‘screening factor’, defined for the f-layer as

Here we use the primed susceptibilities \({\epsilon }_{0}{\chi }_{i}^{\prime}=\mathrm{d}{P}_{i}/\mathrm{d}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\), which are all but guaranteed to be positive. (The change in polarization—local or global—will always follow the change in the external field.) The inverse permittivity of the f-layer can then be written as

Further, as detailed in Supplementary Note 1, we can derive the voltage response of the dielectric layer \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) as

Voltage amplification (VA) corresponds to \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}} > 1\). This key quantity is fully determined by trivial geometric elements and the screening factor of the f-layer.

We now discuss the dielectric response of a superlattice. Typically the ferroelectric layers will be more responsive than the dielectric ones, so that \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{\prime} > {\chi }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\prime}\). From equation (3), the induced depolarizing field \(\mathrm{d}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\mathrm{nd,f}}}\) will oppose \(\mathrm{d}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\), and hence φf < 0. One expects the induced field to be smaller in magnitude than the applied one, so that −1 < φf < 0. It follows that \({\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1} > 0\) and \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}} < 1\), a behaviour we may call normal.

Imagine we make the ferroelectric more responsive, for example by varying its temperature to approach the Curie point. We can eventually reach a situation where the induced \(\mathrm{d}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ind,f}}}}}\) compensates the applied \(\mathrm{d}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\) (φf = −1), and the voltage drops exclusively in the dielectric layers (\({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}=1\)). The ferroelectric effectively behaves as a metal; we call this ‘perfect screening’.

If we keep softening the f-layer so that \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{\prime}\gg {\chi }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\prime}\), we access a regime where the ferroelectric ‘over-screens’2: its response is so strong that the induced depolarizing field exceeds the applied one (φf < −1). This yields NC (\({\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1} < 0\)) and VA in the dielectric (\({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}} > 1\)).

Our formulas show that NC and VA can be obtained from the layer polarizations, readily available from the ‘second-principles’ simulations18,19,20 used to explain NC in PbTiO3/SrTiO3 (PTO/STO) superlattices4,5 (Methods). We now use said methods to monitor the dependence of NC and VA on the design variables offered by these materials (layer thickness, epitaxial strain).

We study PTO/STO superlattices where the PTO and STO layers have a thickness of n and m perovskite cells, respectively, denoted n/m in the following. We consider n and m from 3 to 9, and investigate the response to small fields along z. We also vary the epitaxial strain η between −1% and +3%, choosing the STO substrate as the zero of strain.

We restrict ourselves to low temperatures (formally, 0 K) and work with periodically repeated supercells that are relatively small in plane (8 × 8 perovskite units). This is sufficient to draw conclusions on the behaviour of real materials at ambient conditions.

Let us first recall the main effect epitaxial strain has on PTO/STO superlattices, as obtained from our simulations. Figure 2a shows the ground state of the 6/6 system for η = −1%: it presents stripe domains in the PTO layer, with local polarizations along the out-of-plane (OOP) z direction. This ‘multi-OOP’ state has been thoroughly studied4,21,22,23,24,25,26.

a–d Multi-OOP state for η = −1% of a 6/6 superlattice (a), mono-IP state for η = 1% (b), and mixed states for η = 0.1% (c) and 0.4% (d). Arrows represent local polarization in the xz plane and the colour scale corresponds to the polarization along y. The zero of strain corresponds to the lattice constant of bulk STO (3.901 Å).

For large enough tensile strains, we find the PTO layer displays a monodomain state with in-plane (IP) polarization (Fig. 2b). This simulated ‘mono-IP’ configuration is characterized by Px = Py. In reality27, one typically observes the so-called a1/a2 multidomain configuration, with local polarizations alternating between Px and Py. Our monodomain result is a consequence of the relatively small size of the simulation supercell.

Finally, Fig. 2c,d shows states we obtain in some superlattices at intermediate η values, where mono-IP and multi-OOP features mix, reminiscent of similar findings in the literature26,27. Thus, apart from some non-essential size effects, our simulations capture the evolution of PTO/STO superlattices with epitaxial strain.

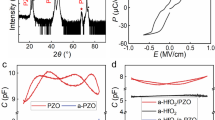

Figure 3a–d shows detailed results for the 3/3 system. At compressive and slightly tensile strains, we get a multi-OOP solution similar to that of Fig. 2a, with ∣Pz∣ ≠ 0 and Px = 0. As η increases, we see a transition to the mono-IP phase with ∣Pz∣ = 0 and Px ≠ 0. This transition is discontinuous, both the multi-OOP and mono-IP states being stable at intermediate strains (grey area in the figure).

a–h, Simulation results for the 3/3 (a–d) and 9/9 (e–h) superlattices, as a function of epitaxial strain. Panels a and e show two superlattice averages of the polarization: \(\left|{P}_{z}\right|\) corresponds to averaging the absolute value of the z-component of the local polarizations, so as to get a non-zero result in the multi-OOP state; Px is the direct supercell average of the x-component of the local polarizations, where x is the modulation direction (perpendicular to the domain walls) in the multi-OOP and mixed states. Panels b and f show two components, χxx and χzz, of the (global) dielectric susceptibility tensor. Panels c and g show the inverse permittivity \({\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1}\) in units of \({\epsilon }_{0}^{-1}\) (left axis) and screening factor φf (right axis) of the ferroelectric layer. Panels d and h show the voltage ratio \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) of the dielectric. The grey zone in panels a–d marks the region where both multi-OOP and mono-IP states are (meta)stable. Dark-coloured down-pointing triangles correspond to multi-OOP states, while we use light-coloured stars for mixed states and empty up-pointing triangles for mono-IP states.

The global dielectric susceptibility is shown in Fig. 3b. As we increase η in the multi-OOP state, we induce a maximum of χxx, signalling the occurrence of an IP polar instability. In the mono-IP state, it is χzz that peaks as η decreases, indicating a soft OOP polar mode. The mono-IP state also displays a peak in χxx at η ≈ 0.6%; this feature, associated to STO and not essential here, is discussed in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Figure 3c shows the inverse permittivity (green) and screening factor (orange) of the f-layer. For all considered strains we get \({\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1} < 0\) and the associated overscreening (φf < −1). Figure 3d shows the corresponding VA in the d layer, which reaches values as high as 12 as the mono-IP state approaches its stability limit. This giant amplification is related to the maximum in χzz (Fig. 3b), in turn connected to the OOP polar instability of the PTO layer. By contrast, the destabilization of the multi-OOP state upon increasing η— which involves a χxx anomaly—does not result in any feature in \({\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1}\) or \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\).

The 9/9 superlattice presents a similar behaviour (Fig. 3e–h), except we find a gradual transformation from multi-OOP to mono-IP, for η between 0.0% and 0.8%, with the occurrence of the mixed state mentioned above (Fig. 2c,d). The small jump in Px around η = 0.9% is related to the occurrence of an IP polarization in the STO layer (not relevant here; Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

The 9/9 superlattice displays its largest NC response in this intermediate region, reaching fivefold amplifications at the transition between the mono-IP and mixed states. Interestingly, the multi-OOP state of the 9/9 superlattices shows a peculiar behaviour: see for example \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}} < 0\) at η = −0.5% in Fig. 3h. In this regime, the PTO layer is in a very stable (stiff) multidomain configuration, while the in-plane compression makes STO electrically soft along z. Hence, the roles reverse and the STO layer displays NC. (More in Supplementary Note 3.) A similar behaviour has been predicted for BaTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattices13.

We run the same study for a large collection of superlattices; Fig. 4a–c summarizes our results. We find the transition region between the multi-OOP and mono-IP states becomes wider for thicker PTO, reflecting the fact that broader layers can accommodate more complex dipole orders, such as the one occurring in the mixed state. (This is consistent with recent observations, for example the occurrence of supercrystals in PbTiO3/SrRuO3 superlattices with PTO layers above 15 cells28.) The mixed state is also favoured by thicker STO layers, a subtle effect probably related to the fact that the stray fields are expelled from the STO layer as it thickens.

a–c Summary of results for VA in n/m superlattices: (a) m = 3, (b) m = 6 and (c) m = 9. The colour scale represents the voltage ratio \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\). The lines and labels indicate the stability regions of the states of Fig. 2. In the coexistence region we show the \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) values corresponding to the mono-IP state.

Most importantly, Fig. 4 confirms that the strongest amplifications occur at the stability limit of the mono-IP state. It also shows that the multi-OOP region is comparatively unresponsive. Let us now get some insight into the physical underpinnings of these behaviours.

According to equations (4) and (6), VA is determined by the screening factor of the f-layer, which in turn depends on the difference in dielectric response between layers. For example, for the 3/3 superlattice at η = 0.3% we get \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\approx 12\), with \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{\prime}=765\) and \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\prime}=721\). This \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{\prime}\) value may seem small; indeed, the ferroelectric is close to developing an OOP polar instability and one would expect susceptibilities around 10,000 (refs. 29,30). By contrast, the computed \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\prime}\) is surprisingly large, as our model for STO yields χ = 202 for the pure material. (Our simulated STO is stiff compared with experimental measurements4.)

The reason for these surprising \({\chi }_{i}^{\prime}\) susceptibilities can be traced back to electrostatics: all layers respond similarly to an external field, to minimize the depolarizing fields. Thus, we expect \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{\prime}\gtrsim {\chi }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\prime}\). For example, for the 6/6 superlattice at η = −1%, which does not display VA, we obtain \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{\prime}=96\) and \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\prime}=95\) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Then, when we move to a region of the phase diagram where the f-layer presents an OOP instability, the energy gain associated to the development of dPf overwhelms the cost of creating a depolarizing field. Hence, the difference between \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{\prime}\) and \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\prime}\) grows a little, sufficient to yield large VA values.

The largest amplifications correspond to the region marking the limit of stability of the mono-IP state. Here the f-layers are in an ‘incipient ferroelectric’ state2,13: they are ready to develop an homogeneous OOP polarization whose occurrence is precluded by the presence of the d-layers. Eventually, as we move towards negative η values, the multi-OOP polar instability freezes in, leading to either a pure multi-OOP state or a mixed state, and hardening the z-polarized ferroelectric soft mode. (This resembles the competition between antipolar and polar orders in antiferroelectrics31,32.) This incipient ferroelectric state corresponds to the idealized picture of monodomain NC2,3; our results predict a realization of this archetype.

As shown in Fig. 5a and previously reported4,5, the NC response of multi-OOP states mainly stems from the strong response (large \(\chi ^{\prime}\)) of the domain walls. By contrast, the NC of the incipient ferroelectric state comes from the whole f-layer (Fig. 5b), which partly explains its superior VA performance.

a, b, Maps of the local dielectric response \({\chi }_{zz}^{\prime}({{{\bf{r}}}})={\epsilon }_{0}^{-1}d P({{{\bf{r}}}})/d {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\), where P(r) is the position dependent z-component of the polarization and the applied field is also along z. The results correspond to a particular xz plane of the 3/3 superlattice at η = 0.4%. (These structures are periodic along y.) The arrows represent the local electric dipoles in the xz plane at zero field. The shown multi-OOP (a) and mono-IP (b) states are both stable for this value of η. Note that the colour scales differ between panels.

Our results thus suggest a strategy to obtain large VA: work with electrostatically induced incipient ferroelectric states that will typically occur at the boundary between IP and OOP phases in ferroelectrics with imperfect screening. Phase boundaries akin to the ones discussed here have been found experimentally in PTO/STO superlattices27 and predicted in other ferroelectric/dielectric heterostructures13. More specifically, PTO/STO superlattices grown on DyScO3 substrates display a coexistence of a1/a2 (IP) and vortex (OOP) states at room temperature27. Further, the balance between such phases can be tuned by controlling the layer thickness33, which should allow stabilization of a1/a2 states on the verge of developing an OOP polarization, thus fulfilling the conditions to present strong overscreening in the ferroelectric layer (φf ≪ −1). Those are clear candidates to display giant incipient ferroelectric VA as predicted here. Let us stress that, despite their limitations (low temperature, only monodomain IP states), our simulations capture the physics of the IP-to-OOP transition; thus, we expect our conclusions to apply to experimentally relevant situations.

Additionally, our formulas teach us that \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) does not depend on the macroscopic permittivity ϵ−1 (equation (6)), while \({\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1}\) does (equation (5)). Hence, one can have behaviours such as that of the 3/3 system at η = −1% (Fig. 3): a very negative \({\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1}\) (Fig. 3c) not accompanied by a large \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) (Fig. 3d). The reason is that this superlattice presents a small χzz (Fig. 3b), which yields large ϵ−1 and \(| {\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1}|\). By the same token, having a globally soft superlattice may result in a modest NC of the f-layer, but this does not necessarily imply a small VA. Hence, for VA purposes, we should not disregard very responsive systems where small values of ϵ−1 or \(| {\epsilon }_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}^{-1}|\) have been observed4,5,16. Rather, we must focus on the response difference between ferroelectric and dielectric layers, as captured by the screening factor φf.

Finally, let us stress that our conclusions are not restricted to an idealized superlattice. Note that an infinite superlattice is equivalent to a ferroelectric/dielectric bilayer contacted with good electrodes, so there is no net depolarizing field. Further, NC is perfectly compatible with non-ideal electrodes and depolarizing fields7; in fact, imperfect screening is at the origin of the effect and can be engineered to induce it2,6,9. Hence, we expect our conclusions to apply to real systems whenever the development of an homogeneous polar state is precluded, including field-effect transistors featuring a ferroelectric/semiconductor bilayer.

We hope this work will bring an impetus to the study of NC, shifting the focus to the quantification and optimization of voltage amplification.

Methods

The second-principles simulations are performed using the SCALE-UP package18,19,20 and the same approach as previous studies of PTO/STO superlattices4,25,34. The superlattice models are based on potentials for the pure bulk compounds—fitted to first-principles results18—and adjusted for the superlattices as described in ref. 4.

We study a collection of n/m superlattices with layer thicknesses n, m = {3, 6, 9}. Further, we consider an isotropic epitaxial strain η between −1% and 3%, where the STO square substrate (with lattice constant of 3.901 Å) is taken as the zero of strain. Note that STO is a convenient reference on account of the popularity of this substrate in experimental investigations and the fact that it lies on the verge of the OOP-to-IP transformation. Additionally, the STO substrate closely matches the in-plane lattice constant of PTO in the OOP state.

We work with a simulation supercell that contains 8 × 8 perovskite unit cells in the xy plane (perpendicular to the stacking direction). In the z direction, only one superlattice period is considered. Periodic boundary conditions are assumed.

To find the lowest-energy state of an n/m superlattice at a given η and electric field value, we relax the atomic structure by performing Monte Carlo simulated annealings. During the annealings, all atomic positions and strains are allowed to vary, except for the in-plane strains imposed by the substrate. From the resulting atomic structures, we compute local electric dipoles within a linear approximation (that is, we consider the atomic displacements with respect to the high-symmetry reference structure and multiply them by their corresponding Born charge tensors), as customarily done in second-principles studies4.

To compute responses, a small external field of 0.2 MV cm−1 is considered. We checked that this field is small enough to obtain susceptibilities and the other relevant quantities within a linear approximation.

We should mention that it is possible to study materials under various electric boundary conditions (that is, at constant electric field35 or constant displacement36) directly from first principles. Yet, here we adopt a second-principles approach for the sake of computational feasibility. The smallest case simulated in this work (3/3 superlattice) contains 1,920 atoms; the largest (9/9) involves 5,760. Systems of this size remain all but untreatable with today’s first-principles methods.

Finally, let us note that STO is far from being a passive dielectric layer. Indeed, it features structural instabilities of its own: antiphase rotations of the O6 groups that are reproduced by our second-principles model18 and present in our simulations. Further, the O6 tilts compete with an incipient ferroelectric order37, and said polar order can be stabilized under epitaxial strain38. These effects, and their impact on some of our results, are mentioned in the main text of this article and further addressed in Supplementary Notes 2 and 3. In addition, Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4 summarize the behaviour of a pure STO film as a function of epitaxial strain, as predicted by our second-principles model.

References

Landauer, R. Can capacitance be negative? Collect. Phenom. 2, 167–170 (1976).

Íñiguez, J., Zubko, P., Luk’yanchuk, I. & Cano, A. Ferroelectric negative capacitance. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 243–256 (2019).

Salahuddin, S. & Datta, S. Use of negative capacitance to provide voltage amplification for low power nanoscale devices. Nano Lett. 8, 405–410 (2008).

Zubko, P. et al. Negative capacitance in multidomain ferroelectric superlattices. Nature 534, 524–528 (2016).

Yadav, A. K. et al. Spatially resolved steady-state negative capacitance. Nature 565, 468–471 (2019).

Bratkovsky, A. M. & Levanyuk, A. P. Very large dielectric response of thin ferroelectric films with the dead layers. Phys. Rev. B 63, 132103 (2001).

Bratkovsky, A. M. & Levanyuk, A. P. Depolarizing field and ‘real’ hysteresis loops in nanometer-scale ferroelectric films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 253108 (2006).

Ponomareva, I., Bellaiche, L. & Resta, R. Dielectric anomalies in ferroelectric nanostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 227601 (2007).

Stengel, M., Vanderbilt, D. & Spaldin, N. A. Enhancement of ferroelectricity at metal-oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 8, 392–397 (2009).

Islam Khan, A. et al. Experimental evidence of ferroelectric negative capacitance in nanoscale heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 113501 (2011).

Luk’yanchuk, I., Sené, A. & Vinokur, V. M. Electrodynamics of ferroelectric films with negative capacitance. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024107 (2018).

Lynch, K. A. & Ponomareva, I. Negative capacitance regime in ferroelectrics demystified from nonequilibrium molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 102, 134101 (2020).

Walter, R., Prosandeev, S., Paillard, C. & Bellaiche, L. Strain control of layer-resolved negative capacitance in superlattices. npj Computational Mater. 6, 186 (2020).

Stengel, M. & Spaldin, N. A. Origin of the dielectric dead layer in nanoscale capacitors. Nature 444, 679–682 (2006).

Aguado-Puente, P. & Junquera, J. Ferromagneticlike closure domains in ferroelectric ultrathin films: First-principles simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 177601 (2008).

Das, S. et al. Local negative permittivity and topological phase transition in polar skyrmions. Nat. Mater. 20, 194–201 (2021).

Pavlenko, M. A., Tikhonov, Y. A., Razumnaya, A. G., Vinokur, V. M. & Lukyanchuk, I. A. Temperature dependence of dielectric properties of ferroelectric heterostructures with domain-provided negative capacitance. Nanomaterials 12, 75 (2021).

Wojdeł, J. C., Hermet, P., Ljungberg, M. P., Ghosez, P. & Íñiguez, J. First-principles model potentials for lattice-dynamical studies: general methodology and example of application to ferroic perovskite oxides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 25, 305401 (2013).

García-Fernández, P., Wojdeł, J. C., Íñiguez, J. & Junquera, J. Second-principles method for materials simulations including electron and lattice degrees of freedom. Phys. Rev. B 93, 195137 (2016).

SCALE-UP, an implementation of second-principles density functional theory. https://www.secondprinciples.unican.es/

Zubko, P., Stucki, N., Lichtensteiger, C. & Triscone, J. M. X-Ray diffraction studies of 180∘ ferroelectric domains in PbTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattices under an applied electric field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 187601 (2010).

Zubko, P. et al. Electrostatic coupling and local structural distortions at interfaces in ferroelectric/paraelectric superlattices. Nano Lett. 12, 2846–2851 (2012).

Aguado-Puente, P. & Junquera, J. Structural and energetic properties of domains in PbTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattices from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 85, 184105 (2012).

Yadav, A. K. et al. Observation of polar vortices in oxide superlattices. Nature 530, 198–201 (2016).

Das, S. et al. Observation of room-temperature polar skyrmions. Nature 568, 368–372 (2019).

Baker, J. S. & Bowler, D. R. Polar morphologies from first principles: PbTiO3 films on SrTiO3 substrates and the p(2 × Λ) surface reconstruction. Adv. Theory Simul. 3, 2000154 (2020).

Damodaran, A. R. et al. Phase coexistence and electric-field control of toroidal order in oxide superlattices. Nat. Mater. 16, 1003–1009 (2017).

Hadjimichael, M. et al. Metal–ferroelectric supercrystals with periodically curved metallic layers. Nat. Mater. 20, 495–502 (2021).

Lines, M. E. & Glass, A. M. Principles and Applications of Ferroelectrics and Related Materials. Oxford Classic Texts in the Physical Sciences (Clarendon Press, 1977).

Graf, M. & Íñiguez, J. A unified perturbative approach to electrocaloric effects. Commun. Mater. 2, 60 (2021).

Kittel, C. Theory of antiferroelectric crystals. Phys. Rev. 82, 729–732 (1951).

Lu, H. et al. Probing antiferroelectric-ferroelectric phase transitions in PbZrO3 capacitors by piezoresponse force microscopy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003622 (2020).

Hong, Z. et al. Stability of polar vortex lattice in ferroelectric superlattices. Nano Lett. 17, 2246–2252 (2017).

Shafer, P. et al. Emergent chirality in the electric polarization texture of titanate superlattices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 915–920 (2018).

Souza, I., Íñiguez, J. & Vanderbilt, D. First-principles approach to insulators in finite electric fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 117602 (2002).

Stengel, M., Spaldin, N. A. & Vanderbilt, D. Electric displacement as the fundamental variable in electronic-structure calculations. Nat. Phys. 5, 304–308 (2009).

Zhong, W. & Vanderbilt, D. Competing structural instabilities in cubic perovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2587 (1995).

Haeni, J. H. et al. Room-temperature ferroelectricity in strained SrTiO3. Nature 430, 758–761 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) (grant No. INTER/RCUK/18/12601980 to M.G and J.Í., and grant No. FNR/C18/MS/12705883/REFOX/Gonzalez to H.A.) and by the United Kingdom’s EPSRC (grant No. EP/S010769/1 to P.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work was executed by M.G., conceived and supervised by J.Í. All authors followed the development of the research, discussed the results and next steps and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks Turan Birol and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–4 and Figs. 1–4.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Structural data, unformatted text.

Source Data Fig. 3

Raw data for figs, table in xlsx file.

Source Data Fig. 4

Raw data for figs, table in xlsx file.

Source Data Fig. 5

Raw data for fig., unformatted text.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Graf, M., Aramberri, H., Zubko, P. et al. Giant voltage amplification from electrostatically induced incipient ferroelectric states. Nat. Mater. 21, 1252–1257 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01332-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01332-z

This article is cited by

-

Theoretical approach to ferroelectricity in hafnia and related materials

Communications Materials (2023)