Abstract

Human activities are degrading ecosystems worldwide, posing existential threats for biodiversity and humankind. Slowing and reversing this degradation will require profound and widespread changes to human behaviour. Behavioural scientists are therefore well placed to contribute intellectual leadership in this area. This Perspective aims to stimulate a marked increase in the amount and breadth of behavioural research addressing this challenge. First, we describe the importance of the biodiversity crisis for human and non-human prosperity and the central role of human behaviour in reversing this decline. Next, we discuss key gaps in our understanding of how to achieve behaviour change for biodiversity conservation and suggest how to identify key behaviour changes and actors capable of improving biodiversity outcomes. Finally, we outline the core components for building a robust evidence base and suggest priority research questions for behavioural scientists to explore in opening a new frontier of behavioural science for the benefit of nature and human wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

A recent global synthesis estimates that 75% of Earth’s land surface has been fundamentally altered by human activities, 66% of the ocean has been negatively affected, and 85% of wetland areas have been lost1. The combined effects of land-use change and habitat fragmentation, overharvesting, invasive species, pollution and climate change have resulted in an average decline in monitored populations of vertebrates of nearly 70% since 1970 and extinction rates that are orders of magnitude higher than the average seen in the geological record2,3,4. The threats to species are so severe that there is growing scientific consensus that we are entering the sixth mass extinction—the fifth being the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago that eliminated all non-avian dinosaurs5.

The rapid degradation of ecosystems and associated loss of species is of profound importance for at least three reasons. First, there are powerful moral arguments that people should not cause the avoidable extinction of perhaps one million or more species6. It is beyond the scope of this paper to describe such arguments, but philosophers have discussed the ethics of biodiversity conservation7,8,9 and social scientists have identified public support for assigning moral value to nature10,11,12. Second, human prosperity depends on wild habitats and species for a host of essential benefits, from climate regulation, biogeochemical and flood regulation to food production and the maintenance of mental wellbeing13,14. Their deterioration thus presents an existential challenge1. Third, evidence suggests that pandemics resulting from greater disease transmission between humans and wild animals15,16 will become more regular features of the future unless our interactions with wild species changes fundamentally15,17,18,19,20. The COVID-19 pandemic—with devastating effects on societies and economies worldwide—most probably emerged from interactions between people and wild animals in China and illustrates the unforeseen consequences that can arise from human encroachment into wild habitats and from poorly regulated exploitation of biodiversity17,21.

Humanity’s impacts on biodiversity are the result of our actions, from unsustainable wildlife harvesting to the rising demand for environmentally damaging foods1,22,23,24,25. Importantly, these actions are undertaken by actors in myriad roles—including consumers, producers and policymakers—who directly or indirectly impact ecosystems and wild species26. For example, the rapid clearance of the Amazon is driven by the actions of consumers across the globe who eat beef, regional policymakers who undervalue forest retention, and ultimately local ranchers who are incentivised to convert forest to pasture27,28. Similarly, the illegal trade in wildlife (for example, rhino horn, pangolin scales, tiger bones and elephant ivory) involves suppliers who hunt the animals, intermediaries (and perhaps corrupt enforcement agents) who facilitate trade and transport the products to market, and domestic and international consumers24,29,30,31. The impacts of people’s behaviour on biodiversity are of course not only manifest in less developed countries. For example, the continued illegal persecution of birds of prey in UK uplands is the result of choices by some gamekeepers to shoot and poison raptors to limit their predation of red grouse, by some hunters to pay exceptionally high prices for large daily ‘bags’ of grouse, and by policymakers to resist attempts at tighter regulation of the shooting industry32.

Because human activities are responsible for driving ecosystem decline, reversing current trends will require profound and persistent changes to human behaviour across actors and scales33. Despite its critical importance, the science of behaviour change has not been a principal focus of research in conservation science and is rarely applied in practical efforts to address major threats to biodiversity (for example, habitat loss and degradation, overharvesting of resources and species, and invasive species)33,34,35,36,37 (A.B. et al., manuscript in preparation). Conservation scientists (defined broadly to include researchers across the natural and social sciences seeking to understand and mitigate these threats) have generally been slow to incorporate evidence from behavioural science into their theories and interventions33,36,38,39,40,41. Conversely, biodiversity conservation has also not been a strong focus of study for behavioural scientists (defined broadly to include those engaged in the scientific study of behaviour across diverse disciplines, including psychology, sociology, economics, anthropology and political science). One exception is research on common-pool resource management and commons dilemmas, which has a long history tracing back to the 1970s42,43,44,45. This research tradition has tackled issues closely linked to biodiversity conservation and foreshadows many contemporary and interdisciplinary analyses. More recently, social-marketing techniques have been used to tackle a variety of biodiversity problems and their potential is increasingly recognised46,47,48,49,50. For example, a recent study in the Philippines, Indonesia and Brazil used locally tailored social-marketing campaigns to shift social norms and increase sustainable fishing among communities of small-scale fisheries50. But while the number of successful applications of behavioural science to biodiversity conservation is increasing, they remain rare and often suffer from methodological limitations51. The conservation evidence base is consequently patchy and generally poorly informed by behavioural science36,52.

Meanwhile, in other contexts, behavioural science has made substantial gains in understanding how to encourage prosocial behaviour, including actions that ultimately affect biodiversity outcomes. A growing body of research related to climate change suggests the importance of social norms, risk communication, emotion and choice architecture in changing behaviour53,54,55,56,57. Behavioural science has been incorporated into some public efforts to encourage sustainable land management in the United States and the European Union58,59,60,61,62. Nevertheless, there are still few applications of behavioural science to explicitly address the most important proximate causes of biodiversity loss. Behavioural insights from research related to climate change, land management, consumer behaviour, voting, collective action and programme enrolment can inform the multi-scale approach needed to deliver effective biodiversity conservation, but this research has not been systematically linked to address biodiversity conservation problems. Moreover, the literature is heavily focused on households and is not well-developed for other important actors57,63. We therefore see unrealised potential for behavioural science to address the escalating biodiversity crisis.

Increasing scientific engagement

Behavioural scientists might be motivated to become engaged in biodiversity conservation research for at least three reasons. First, biodiversity conservation is essential for the long-term prosperity of people and nature. Its particular characteristics (see below) mean that it would be unhelpful simply to adopt behaviour-change interventions found effective in other domains: indeed, these do not necessarily generalize to biodiversity conservation52,64. Instead, the field offers a new arena for exploring important research questions and for testing novel interventions. Behavioural science research that focuses specifically on biodiversity conservation can contribute to the mitigation of a global and existential threat.

Second, engaging in biodiversity conservation research offers behavioural scientists a chance to investigate theories and interventions in new contexts and populations65,66,67. A key requirement for increasing the generalizability of behavioural science is to ramp up research activities outside North America, Australia and Europe68,69. Due to the importance of the tropics for biodiversity, the focus of many conservation interventions is in Africa, Latin America and Asia, providing opportunities to test theory and interventions in contexts which are less ‘WEIRD’ (western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic). A related challenge is the need to shift behaviours of many different kinds of actors. Behaviour-change interventions in other sectors have been criticised for being too narrowly focused on end-users70,71: Conservation problems provide opportunities for targeting the behaviours of a far broader array of stakeholders. Moreover, conserving biodiversity often requires coordinated action across local, national and global actors, heterogeneous cultures and divergent financial interests, with the benefits of conservation commonly accruing to geographically and psychologically distant communities and indeed non-human species.

Finally, conservation scientists and practitioners are keen to collaborate more with behavioural scientists72,73. An increasing number of conservation scientists and practitioners recognise the need for stronger integration with behavioural science in order to design interventions that are grounded in greater understanding of the social, motivational and contextual drivers of people’s actions33,39,74,75. Naturally, as with all interdisciplinary collaborations, these collaborations will have their challenges75. However, recent examples show that effective collaborations can produce novel and mutually beneficial research that suggests practical routes to achieving behaviour change for biodiversity conservation50,64,76,77,78.

The remainder of this Perspective seeks to encourage greater engagement of behavioural scientists in conservation-targeted research and practice. We first highlight the diversity of actors involved in threats to biodiversity and the scope of behaviour changes required. In doing so, we propose routes to identifying key behaviour changes and prioritising among them on the basis of their potential for improving biodiversity outcomes. We suggest research questions for better understanding how to influence different actors’ behaviours and for improving conservation interventions, and close by making recommendations for how to expand the conservation evidence base systematically.

Identifying key actors and behaviour changes

Threats to biodiversity are rarely caused by a single action of a single actor. Rather, they typically result from multiple behaviours by multiple actors over large spatial and temporal scales36,79. It can thus be very challenging to identify those behaviour changes with the greatest promise of being achieved and of positively impacting biodiversity. Doing so requires specifying conservation targets (e.g., particular populations or ecosystems), and then systematically considering the proximate causes and underlying drivers of threats to them, the actors involved (for example, producers and consumers), and the harmful behaviours performed by those actors26,39,45,80.

The proximate threats to wild species and the places they live can be categorised into four main groups: habitat loss and degradation, overharvesting, invasive species, and climate change and pollution81,82,83. These threats also interact, with species or ecosystems commonly impacted by multiple threats, sometimes with amplifying effects. For example, the spread of some invasive plants is thought to be exacerbated by elevated nitrogen deposition and atmospheric CO2 concentrations84,85. Proximate threats are driven by broader societal processes, including rising demand for food and consumer goods, weak local, national and international institutions that struggle to ensure the protection of public goods (including against corrupt actors), population growth and the growing disconnect of people from nature due to increasing urbanization and indoor recreation86. Many of the interventions conservationists deploy to tackle proximate threats, such as removing invasive species, restoring wetlands or propagating threatened species in captivity, are not primarily about changing people’s behaviour (although even in these examples those carrying out the management actions must be trained and incentivised, and behaviours must change if these threats are not to recur). However, given the pervasive importance of human activities in conservation problems, many interventions do involve attempts to alter behaviour. If behavioural science is to improve the effectiveness of these efforts, an important first step is to identify the main actors responsible for a given threat and the changes in their behaviour that might be required to alleviate it.

One tool for mapping the actors and behaviours impacting a conservation target is to build a threat chain (A.B. et al., manuscript in preparation). This is a simplified summary of knowledge of the reasons for the unfavourable status of a species or ecosystem, from changes in ecological dynamics to the socioeconomic mechanisms thought to be responsible, and their underlying drivers. Once this putative causal chain has been constructed, the main actors in the chain can be identified, along with changes in their behaviour that might potentially reduce the particular threat. Where conservation targets are impacted by multiple threats this process can be repeated, with the likely impact of different behaviour changes compared across threats in order to identify the most promising interventions for delivering those changes.

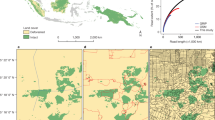

Using Amazon deforestation (as an example of habitat loss) for illustration27,28 (Fig. 1, red boxes), the extirpation of forest-dependent species and ecosystem processes resulting from conversion to pasture has been caused (inter alia) by a combination of rising global demand for beef, poor pasture and livestock management, the absence of incentives for forest retention and the practice of establishing de facto land tenure via forest clearance. Underlying drivers include weak governance at multiple levels and rising per capita demand for beef among a growing population in Brazil and beyond. Potential behaviour changes that might be targeted to reduce deforestation (blue boxes) include increased enforcement of forest protection legislation by government agencies, improved pasture and stock management by ranchers, a reduction in per capita demand for beef among domestic and international consumers, and an accelerated decline in human population growth in high-consumption countries.

This example characterizes (in red boxes) the threat to the Amazon forest from conversion to cattle pasture. Potentially beneficial changes in the behaviours are in blue boxes. This threat chain addresses only one of several interacting threats impacting the conservation target. The threat chain model is adapted from Balmford et al.26.

As a heuristic, we conducted this threat-mapping exercise for 12 examples chosen to represent different threat processes and the diversity of ecological and socioeconomic contexts in which they arise (A.B. et al., manuscript in preparation). We identified nine main clusters of actors (rows in Fig. 2), classified by how their behaviour impacts conservation targets. Producers and extractors of natural resources, conservation managers and consumers are commonly identified as targets for behaviour-change interventions in conservation and other sectors. However, we also identified other actor groupings, including manufacturers and sellers, investors, policymakers, voters, communicators and lobbyists, all of whom may have considerable—usually indirect—influences on conservation outcomes, yet are commonly overlooked when it comes to behaviour-change interventions. Because our clusters of actors are operationally defined, they align well with the diversity of behaviour changes we identified (Fig. 2, right column), including reducing consumers’ purchases of high-footprint items and directing investors’ investments towards less damaging production technologies. Our clusters can also be mapped onto more conventional organisational groups (such as citizens or businesses; Fig. 2, ‘Actor—defined by group’ columns), but because such organizational groups impact conservation targets in heterogeneous ways, their correspondence with behaviour changes is much weaker than for our typology.

Prioritising behaviour changes

After examining all major threats to a given conservation target and identifying promising behaviour changes involving specified actors, the next step is to prioritise behaviour changes and, in turn, the interventions potentially capable of achieving them. We suggest this should focus on two main characteristics that together determine the impact of behaviour-change interventions57,87. The first is the target behaviour’s potential, if changed, to improve the state of the conservation objective (by analogy with the climate change literature, its technical potential). In the Amazon example (Fig. 1), both enforcing forest protection laws and providing herd management support that is conditional on ranchers stopping clearance might be considered to have greater technical potential than slowing population growth in beef-consuming countries (which may have only limited effect if per capita demand continues to rise). Prioritising behaviours for research and intervention on the basis of their technical potential—considered an omission in behavioural science contributions to climate change mitigation57,88,89,90—ensures that resources and efforts are allocated toward the behaviours with the greatest potential to effectively mitigate biodiversity threats.

The second aspect to consider in prioritization is the behaviour’s plasticity, which refers to the degree to which a target behaviour can be changed by a specified intervention57. For example, to what extent can behaviour-change interventions increase the share of plant-based food in overseas or Brazilian diets, or improve the cattle and pasture management of Amazonian farmers? Due to the current paucity of conservation-focused behaviour-change interventions, good estimates of behavioural plasticity will often be lacking. Instead, it will often be necessary to use evidence from interventions targeting comparable behaviours relating to other actors, contexts or domains until more direct data become available87. Although considerations of technical potential and behavioural plasticity should guide the selection of behaviours to study and intervene against, we note that additional considerations may become pertinent when selecting interventions for implementation (for example, feasibility, stakeholder support and costs)91,92,93.

Given the range of actors involved in causing ecosystem change and the complexity of their behaviour, standalone behaviour-change interventions are unlikely to effectively mitigate a biodiversity threat (as illustrated in Fig. 1). Individual-level interventions—for example, targeting specific farmers, manufacturers, or investors—may well form an important part of the solution, but they will usually be insufficient on their own. For example, successfully incentivising ranchers in one Amazonian municipality to retain their remaining forests will be of little benefit to biodiversity if prevailing market failure or weak institutions continue to incentivise forest clearance elsewhere. Tackling more systemic drivers, such as environmentally damaging subsidy regimes, corporate interests, poor governance and persistent norms, also necessitates population-level interventions that can alter economic systems, institutional systems and physical infrastructure. Importantly, the intent here is not to undermine the legitimacy of individual-level interventions—quite the contrary. Systemic changes also cannot be achieved without individual-level behaviour changes and support57,94,95. Different levels of intervention must work in concert, which requires a holistic understanding of the determinants of human behaviour.

Building a robust evidence base

Generating evidence on behaviour-change interventions for biodiversity conservation demands a mix of methods, including experimental and observational studies using quantitative and qualitative techniques96,97,98. Critically, to build an evidence base, these studies must be based on mapping and synthesizing the existing literature99. They also need to be embedded in relevant conceptual or theoretical frameworks, coupled with a theory of change, and designed with the statistical power to answer the study questions. This might include, for example, taking a systems perspective98, as well as using a taxonomy or typology of interventions100,101.

Behavioural responses and the effectiveness of interventions are likely to vary between social and cultural contexts. Assessing the effect size of interventions in different settings will be key to building a robust evidence base that has global application. Improving the cross-cultural profile of behavioural science evidence is thus imperative, and particularly so for biodiversity conservation, where many problems are centred outside Europe and North America. Achieving this will, however, be challenging given that the research capacity in behavioural science remains low in high-income countries and even lower elsewhere. International partnerships will therefore be an important strand of building capacity across regions.

Emergent research questions

Given that behavioural science research into conservation-related problems is still in its infancy, many important questions remain unanswered. In this final section, we outline four higher-order questions that we believe could impact the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing people’s negative impacts on biodiversity, natural habitats and the services provided by ecosystems. While these questions can apply to prosocial behaviour more broadly, we believe that there is considerable merit in tackling them within the context of biodiversity conservation, in part through devising and testing novel interventions in the field. This will necessitate close collaboration between behavioural scientists and conservation scientists and practitioners.

The first research question deals with prioritization. As with climate change interventions, there is a clear need for a more systematic understanding of the technical potential of different behaviour changes: which ones, if delivered, would be most likely to reduce a threat and thereby enhance the status of the conservation target, taking into account other threats it faces80,91? Given the focus of many recent environmental interventions on appealing, tractable but relatively low-impact behaviour changes (for example, eating more locally grown food or avoiding plastic drinking straws), such prioritization is badly needed88,90. One challenge in identifying priorities may be the complexity of conservation outcomes: estimating probable impacts of behaviour changes on highly interconnected ecosystems may be more difficult than impacts on greenhouse gas levels80, but we suggest that this is a surmountable problem. A further consideration here is how far a behaviour change addressing one conservation issue might reduce (or indeed increase) threats to other conservation targets102.

The remaining research questions are all aimed at improving our understanding of the plasticity of priority behaviours (that is, those with high technical potential to improve biodiversity outcomes91). Our second suggested question is which interventions work best to alter priority behaviours, and how does this vary across contexts? One key aspect is exploring how the suitability of behaviour-change interventions varies with the level of deliberation and perceived importance of the decision being made. Consider contrasting interventions aimed at increasing how often consumers buy sustainably (rather than unsustainably) sourced fish. For someone making a weekly shopping trip such a choice may be performed with limited deliberation, which means that interventions targeting automatic decision-making processes may be effective103. However, for other actors, such as supply-chain managers making bulk purchases for supermarkets, different interventions—perhaps motivated by limiting reputational risk—will probably be required. At the level of decision makers designing national or international fisheries policy, other sorts of interventions104—potentially linked to cessation or realignment of taxpayer subsidies—might need to be considered.

This example also illustrates our third suggested research question: how does the effectiveness of behaviour-change interventions vary with the financial and psychological costs of the change for the target actor? Differences in motivation will be important here. In some instances, actors may benefit directly from pro-conservation behaviour (for example, because eating more sustainably sourced fish aligns with health values, or keeping their pet cat indoors reduces its risk of injury). But sometimes those choices may carry costs (for example, sustainable seafood may be more expensive or difficult to source). In the case of the supermarket chains, there may be financial and administrative costs to switching suppliers, at least over the short term. Policymakers will also face strong lobbying pressure to continue to support the policy status quo. Clearly, different interventions will be needed across such diverse contexts. Varied interventions may also be needed within actor groups. For example, supermarket chains may differ in their motivations, knowledge, demographics and other interests in ways that warrant different types of behaviour-change interventions.

Lastly, how can practitioners design interventions to ensure that behaviour changes persist over the long term? Although many intervention studies do not evaluate persistence over time, those that do commonly observe that effectiveness wanes105,106,107. In some contexts, it might be possible to design one-off interventions with long-lasting effects, but in others, delivering lasting change may necessitate recurring rounds of intervention or the repeated introduction of novel interventions. Better understanding the persistence of intervention effects will be key to sustaining beneficial behaviour change.

Many more questions will emerge as this field develops. Addressing them will require fresh partnerships and continued commitment to work across disciplines and in unfamiliar circumstances. Such partnerships may follow recommendations for interdisciplinary collaborations around biodiversity conservation108,109 or be inspired by existing programmes and networks (some of which collaborate closely with practitioners), such as the Cambridge Conservation Initiative, Center for Behavioral and Experimental Agri-environmental Research, and Science for Nature and People Partnership. We submit that there are few other opportunities where behavioural scientists have such potential to tackle one of the great challenges of our age. We hope this Perspective can help inspire this critical work.

References

Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services http://rid.unrn.edu.ar/handle/20.500.12049/4223 (IPBES Secretariat, 2019).

Maxwell, S. L., Fuller, R. A., Brooks, T. M. & Watson, J. E. M. Biodiversity: The ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature 536, 143–145 (2016).

Living Planet Report 2020—Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss (WWF, 2020).

Ceballos, G. et al. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400253 (2015).

Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R. & Dirzo, R. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E6089–E6096 (2017).

Tilman, D. et al. Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention. Nature 546, 73–81 (2017).

Partridge, E. Nature as a moral resource. Environ. Ethics 6, 101–130 (1984).

Ehrenfeld, D. in Biodiversity (ed. Wilson, E. O.) 212–216 (National Academy Press, 1988).

Taylor, P. W. The ethics of respect for nature. Environ. Ethics 3, 197–218 (1981).

Clayton, S. in The Virtues of Sustainability (ed. Kawall, J.) Ch. 1 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021).

Feinberg, M. & Willer, R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 24, 56–62 (2013).

Kellert, S. R. The Value of Life: Biological Diversity and Human Society (Island Press, 1997).

Bratman, G. N. et al. Nature and mental health: an ecosystem service perspective. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0903 (2019).

Díaz, S. et al. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science 359, 270–272 (2018).

Gibb, R. et al. Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems. Nature 584, 398–402 (2020).

Balmford, A., Fisher, B., Mace, G. M., Wilcove, D. S. & Balmford, B. COVID-19: Analogues and lessons for tackling the extinction and climate crises. Curr. Biol. 30, R969–R971 (2020).

Dobson, A. P. et al. Ecology and economics for pandemic prevention. Science 369, 379–381 (2020).

Allen, T. et al. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 8, 1124 (2017).

Morens, D. M., Daszak, P., Markel, H. & Taubenberger, J. K. Pandemic COVID-19 joins history’s pandemic legion. mBio 11, e00812-20 (2020).

Wilkinson, D. A., Marshall, J. C., French, N. P., Hayman, D. T. S. & Wilkinson, D. A. Habitat fragmentation, biodiversity loss and the risk of novel infectious disease emergence. J. R. Soc. Interface 15, 20180403 (2018).

Mallapaty, S. Where did COVID come from? WHO investigation begins but faces challenges. Nature 587, 341–342 (2020).

Tilman, D. & Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 515, 518–522 (2014).

Poore, J. & Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 992, 987–992 (2018).

‘t Sas-Rolfes, M., Challender, D. W. S., Hinsley, A., Veríssimo, D. & Milner-Gulland, E. J. Illegal wildlife trade: scale, processes, and governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 44, 201–230 (2019).

Dietz, T. Drivers of human stress on the environment in the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 42, 189–213 (2017).

Balmford, A. et al. Capturing the many dimensions of threat: comment on Salafsky et al. Conserv. Biol. 23, 482–487 (2009).

Nepstad, D. C., Stickler, C. M. & Almeida, O. T. Globalization of the Amazon soy and beef industries: opportunities for conservation. Conserv. Biol. 20, 1595–1603 (2006).

zu Ermgassen, E. K. H. J. et al. Results from on-the-ground efforts to promote sustainable cattle ranching in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability 10, 1301 (2018).

MacFarlane, D. et al. Reducing demand for overexploited wildlife products: Lessons from systematic reviews from outside conservation science. Preprint at OSF https://osf.io/preprints/8935b/ (2020).

Thomas-Walters, L. et al. Motivations for the use and consumption of wildlife products. Conserv. Biol. 35, 483–491 (2021).

Johnson, C. K. et al. Global shifts in mammalian population trends reveal key predictors of virus spillover risk. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20192736 (2020).

Avery, M. Inglorious: Conflict in the Uplands (Bloomsbury, 2015).

Cowling, R. M. Let’s get serious about human behavior and conservation. Conserv. Lett. 7, 147–148 (2014).

Marselle, M., Turbe, A., Shwartz, A., Bonn, A. & Colléony, A. Addressing behavior in pollinator conservation policies to combat the implementation gap. Conserv. Biol. 35, 610–622 (2021).

Saunders, C. D. The emerging field of conservation psychology. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 10, 137–149 (2003).

Selinske, M. J. et al. Revisiting the promise of conservation psychology. Conserv. Biol. 32, 1464–1468 (2018).

Schultz, P. W. Conservation means behavior. Conserv. Biol. 25, 1080–1083 (2011).

Cinner, J. How behavioral science can help conservation. Science 362, 889–891 (2018).

Reddy, S. M. W. et al. Advancing conservation by understanding and influencing human behavior. Conserv. Lett. 10, 248–256 (2017).

Burgess, G. Powers of persuasion? Conservation communications, behavioural change and reducing demand for illegal wildlife products. TRAFFIC Bull. 28, 65–73 (2016).

Kidd, L. R. et al. Messaging matters: A systematic review of the conservation messaging literature. Biol. Conserv. 236, 92–99 (2019).

Ostrom, E. et al. The Drama of the Commons (National Academy Press, 2002).

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E. & Stern, P. C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 302, 1907–1912 (2003).

Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990).

Stern, P. C., Young, O. R. & Druckman, D. E. Global Environmental Change: Understanding the Human Dimensions (National Academy Press, 1992).

Veríssimo, D. The past, present, and future of using social marketing to conserve biodiversity. Soc. Mar. Q. 25, 3–8 (2019).

Veríssimo, D. et al. Does it work for biodiversity? Experiences and challenges in the evaluation of social marketing campaigns. Soc. Mar. Q. 24, 18–34 (2018).

Green, K. M., Crawford, B. A., Williamson, K. A. & DeWan, A. A. A meta-analysis of social marketing campaigns to improve global conservation outcomes. Soc. Mar. Q. 25, 69–87 (2019).

DeWan, A., Green, K., Li, X. & Hayden, D. Using social marketing tools to increase fuel-efficient stove adoption for conservation of the golden snub-nosed monkey, Gansu Province, China. Conserv. Evid. 10, 32–36 (2013).

McDonald, G. et al. Catalyzing sustainable fisheries management though behavior change interventions. Conserv. Biol. 35, 1176–1189 (2020).

Veríssimo, D. & Wan, A. K. Y. Characterizing efforts to reduce consumer demand for wildlife products. Conserv. Biol. 33, 623–633 (2019).

Byerly, H. et al. Nudging pro-environmental behavior: evidence and opportunities. Front. Ecol. Environ. 16, 159–168 (2018).

van der Linden, S., Maibach, E. & Leiserowitz, A. Improving public engagement with climate change: five ‘best practice’ insights from psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 758–763 (2015).

Chapman, D. A., Lickel, B. & Markowitz, E. M. Reassessing emotion in climate change communication. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 850–852 (2017).

Nisa, C. F., Bélanger, J. J., Schumpe, B. M. & Faller, D. G. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nat. Commun. 10, 4545 (2019).

Valkengoed, A. M. Van & Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 158–163 (2019).

Nielsen, K. S. et al. How psychology can help limit climate change. Am. Psychol. 76, 130–144 (2021).

Dessart, F. J., Barreiro-Hurlé, J. & van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: a policy-oriented review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 46, 417–471 (2019).

Palm-Forster, L. H., Ferraro, P. J., Janusch, N., Vossler, C. A. & Messer, K. D. Behavioral and experimental agri-environmental research: methodological challenges, literature gaps, and recommendations. Environ. Resour. Econ. 73, 719–742 (2019).

Wallen, K. E. & Kyle, G. T. The efficacy of message frames on recreational boaters’ aquatic invasive species mitigation behavioral intentions. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 23, 297–312 (2018).

Metcalf, A. L., Angle, J. W., Phelan, C. N., Muth, B. A. & Finley, J. C. More ‘bank’ for the buck: microtargeting and normative appeals to increase social marketing efficiency. Soc. Mar. Q. 25, 26–39 (2019).

Green, K. M., DeWan, A., Arias, A. B. & Hayden, D. Driving adoption of payments for ecosystem services through social marketing, Veracruz, Mexico. Conserv. Evid. 10, 48–52 (2013).

Stern, P. C. & Dietz, T. A broader social science research agenda on sustainability: Nongovernmental influences on climate footprints. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 60, 101401 (2020).

Niemiec, R. M., Sekar, S., Gonzalez, M. & Mertens, A. The influence of message framing on public beliefs and behaviors related to species reintroduction. Biol. Conserv. 248, 108522 (2020).

Watts, D. J. Should social science be more solution-oriented?. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0015 (2017).

Berkman, E. T. & Wilson, S. M. So useful as a good theory? The practicality crisis in (social) psychological theory. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620969650 (2021).

Giner-Sorolla, R. From crisis of evidence to a ‘crisis’ of relevance? Incentive-based answers for social psychology’s perennial relevance worries. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 30, 1–38 (2019).

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J. & Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33, 61–83 (2010).

Rad, M. S., Martingano, A. J. & Ginges, J. Toward a psychology of Homo sapiens: making psychological science more representative of the human population. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 11401–11405 (2018).

Ewert, B. Moving beyond the obsession with nudging individual behaviour: towards a broader understanding of behavioural public policy. Public Policy Adm. 35, 337–360 (2020).

Bhargava, B. S. & Loewenstein, G. Behavioral economics and public policy 102: beyond nudging. Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 396–401 (2015).

Wright, A. J. et al. Competitive outreach in the 21st century: why we need conservation marketing. Ocean Coast. Manag. 115, 41–48 (2015).

Veríssimo, D. & McKinley, E. Introducing conservation marketing: why should the devil have all the best tunes? Oryx 50, 14 (2016).

Nilsson, D., Fielding, K. & Dean, A. J. Achieving conservation impact by shifting focus from human attitudes to behaviors. Conserv. Biol. 34, 93–102 (2020).

Bennett, N. J. et al. Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conserv. Biol. 31, 56–66 (2017).

Nelson, K. M., Partelow, S. & Schlüter, A. Nudging tourists to donate for conservation: experimental evidence on soliciting voluntary contributions for coastal management. J. Environ. Manag. 237, 30–43 (2019).

Niemiec, R. M., Willer, R., Ardoin, N. M. & Brewer, F. K. Motivating landowners to recruit neighbors for private land conservation. Conserv. Biol. 33, 930–941 (2019).

Byerly, H., D’Amato, A. W., Hagenbuch, S. & Fisher, B. Social influence and forest habitat conservation: experimental evidence from Vermont’s maple producers. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1, e98 (2019).

Amel, E., Manning, C., Scott, B. & Koger, S. Beyond the roots of human inaction: fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science 279, 275–279 (2017).

Selinske, M. J. et al. Identifying and prioritizing human behaviors that benefit biodiversity. Conserv. Sci. Pr. 2, e249 (2020).

Diamond, J. M. in Extinctions (ed. Nitecki, M. H.) 191–246 (Univ. Chicago Press, 1984).

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis (Island Press, 2005).

Wilson, E. O. The Future of Life (Vintage, 2002).

Dukes, J. S. & Mooney, H. A. Does global change increase the success of biological invaders? Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 135–139 (1999).

Smith, S. D. et al. Elevated CO2 increases productivity and invasive species success in an arid ecosystem. Nature 408, 79–82 (2000).

Díaz, S. et al. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 366, eaax3100 (2019).

Dietz, T., Gardner, G. T., Gilligan, J., Stern, P. C. & Vandenbergh, M. P. Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce U.S. carbon emissions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18452–18456 (2009).

Stern, P. C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 56, 407–424 (2000).

Stern, P. C. Contributions of psychology to limiting climate change. Am. Psychol. 66, 303–314 (2011).

Nielsen, K. S., Cologna, V., Lange, F., Brick, C. & Stern, P. C. The case for impact-focused environmental psychology. J. Environ. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101559 (2021).

Nielsen, K. S. et al. Improving climate change mitigation analysis: a framework for examining feasibility. One Earth 3, 325–336 (2020).

Vandenbergh, M. P. & Gilligan, J. M. Beyond Politics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

Selinske, M. J. et al. We have a steak in it: eliciting interventions to reduce beef consumption and its impact on biodiversity. Conserv. Lett. 13, e12721 (2020).

Seto, K. C. et al. Carbon lock-in: types, causes, and policy implications. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41, 425–452 (2016).

Marteau, T. M. Towards environmentally sustainable human behaviour: targeting non-conscious and conscious processes for effective and acceptable policies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 375, 20160371 (2017).

Ogilvie, D. et al. Using natural experimental studies to guide public health action: turning the evidence-based medicine paradigm on its head. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 74, 203–208 (2020).

Marteau, T. M., Fletcher, P. C., Hollands, G. J. & Munafo, M. R. in Handbook of Behavior Change (eds. Hagger, M. S. et al.) 193–207 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Rutter, H. et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 390, 2602–2604 (2017).

Sutherland, W. J., Fleishman, E., Mascia, M. B., Pretty, J. & Rudd, M. A. Methods for collaboratively identifying research priorities and emerging issues in science and policy. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2, 238–247 (2011).

Hollands, G. J. et al. The TIPPME intervention typology for changing environments to change behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0140 (2017).

Michie, S. et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 46, 81–95 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Framing sustainability in a telecoupled world. Ecol. Soc. 18, 26 (2013).

Marteau, T. M., Hollands, G. J. & Fletcher, P. C. Changing human behavior to prevent disease: the importance of targeting automatic processes. Science 337, 1492–1495 (2012).

Sumaila, U. R. et al. Updated estimates and analysis of global fisheries subsidies. Mar. Policy 109, 103695 (2019).

Bernedo, M., Ferraro, P. J. & Price, M. The persistent impacts of norm-based messaging and their implications for water conservation. J. Consum. Policy 37, 437–452 (2014).

Ferraro, P. J. & Price, M. K. Using nonpecuniary strategies to influence behavior: evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Rev. Econ. Stat. 95, 64–73 (2013).

Dayer, A. A., Lutter, S. H., Sesser, K. A., Hickey, C. M. & Gardali, T. Private landowner conservation behavior following participation in voluntary incentive programs: recommendations to facilitate behavioral persistence. Conserv. Lett. 11, e12394 (2018).

Kelly, R. et al. Ten tips for developing interdisciplinary socio-ecological researchers. SEPR 1, 149–161 (2019).

Campbell, L. M. Overcoming obstacles to interdisciplinary research. Conserv. Biol. 19, 574–577 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for funding from the Cambridge Conservation Initiative Collaborative, Fund and Arcadia, RSPB and the Gund Institute for Environment, University of Vermont. A.B. is supported by a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit award. E.E.G. was supported by a NERC studentship (grant number NE/L002507/1). We thank P. C. Stern for helpful discussion and feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the research. K.S.N., T.M.M. and A.B. wrote the manuscript. The other contributing authors (J.M.B., R.B.B., S.B., G.B., M.B., H.B., S.C., D.E., P.J.F., B.F., E.E.G., J.P.G.J., M.O., S.P., T.H.R., R.T., S.v.d.L. and D.V.) provided critical comments and revisions. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Human Behaviour thanks Rebecca Niemiec, Philip Seddon and Matthew Selinske for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nielsen, K.S., Marteau, T.M., Bauer, J.M. et al. Biodiversity conservation as a promising frontier for behavioural science. Nat Hum Behav 5, 550–556 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01109-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01109-5

This article is cited by

-

Realizing the full potential of behavioural science for climate change mitigation

Nature Climate Change (2024)

-

A global analysis of coral reef conservation preferences

Nature Sustainability (2023)

-

Pesticides drive patterns of insect visitors and pollination-related attributes of four crops in Buea, Southwest Cameroon

International Journal of Tropical Insect Science (2023)

-

Understanding the social impacts of enforcement activities on illegal wildlife trade in China

Ambio (2022)