Abstract

Human behaviour is central to transmission of SARS-Cov-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and changing behaviour is crucial to preventing transmission in the absence of pharmaceutical interventions. Isolation and social distancing measures, including edicts to stay at home, have been brought into place across the globe to reduce transmission of the virus, but at a huge cost to individuals and society. In addition to these measures, we urgently need effective interventions to increase adherence to behaviours that individuals in communities can enact to protect themselves and others: use of tissues to catch expelled droplets from coughs or sneezes, use of face masks as appropriate, hand-washing on all occasions when required, disinfecting objects and surfaces, physical distancing, and not touching one’s eyes, nose or mouth. There is an urgent need for direct evidence to inform development of such interventions, but it is possible to make a start by applying behavioural science methods and models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

There are many actors whose behaviour is crucial to limiting the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19. These include governments, health and social care organisations, businesses, media outlets and community groups. Decisions they make have far-reaching effects on virus transmission itself and also on the cost to people and society, both of the disease and of the measures taken to control it. These actors form part of a complex, interacting system that needs to be mapped and understood1. At the heart of the system are individual members of communities and their behaviours that are transmitting the virus.

The behavioural sciences seek to understand the psychological, biological, social and environmental factors that influence behaviour with a view to developing interventions and policies to help achieve societal, organisational or personal goals. When it comes to limiting SARS-CoV-2 transmission, they are already being brought to bear on the problem2,3,4,5. They can inform policies to (i) control the infection, (ii) mitigate the harm done by it and the measures taken to control it, and (iii) develop resilience and new patterns of behaviour in preparation for future pandemics5,6. All this is in addition to the very important role that clinical, psychological and social sciences can play in addressing the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and societal functioning6,7.

This paper focuses on adherence to behaviours required to reduce virus transmission. We argue that there is an urgent need to develop and evaluate interventions to promote effective enactment of these behaviours and provides a preliminary analysis to help guide this. This is relevant for the current phase of the pandemic and to reduce the risk of resurgence in months to come and of future pandemics.

Behaviours required to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission

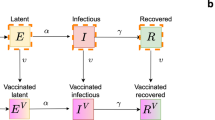

COVID-19 is the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is a novel form of coronavirus8. The virus is transmitted in communities either directly by travelling through the air from an infected person’s airways, mouth or nose to a recipient’s eyes, nose or mouth (the T-zone), or by the virus contaminating an object or surface (fomite) that is touched by a recipient who then goes on to touch their T-zone9. The T-zone is the primary route for the virus to cause infection because the virus enters cells of mucous membranes and lung epithelial tissue8. It does not enter through the skin. The evidence suggests that, in community settings, the virus is carried primarily on respiratory droplets (relatively large particles that typically travel a short distance before falling to a surface) rather than aerosol (small particles than can stay airborne for an extended period)10,11, but this view has been contested12. Figure 1 shows the putative transmission paths and the behaviours that can block them in community (as opposed to healthcares) settings.

Pathways to SARS-CoV-2 transmission and behaviours to block this. Large circles, stages in the pathway; red arrows, routes of transmission; crosses in small circles, blocks to transmission; filled rectangles, personal protective behaviours to block transmission routes. Dotted arrows point to the blocking points. The blue vertical bar shows the points at which isolation and social distancing measures work. Reproduced from ref. 47.

Governments have mainly used isolation (keeping vulnerable and infected or potentially infected people physically away from others) and what has been termed ‘social distancing’ (staying at home except for essential journeys) to block transmission. These are represented by the blue vertical bar in Fig. 1, which separates the infected person and fomites on the left of the diagram from other people on the right. Measures taken to ensure social distancing have included closing all but essential shops and businesses, banning gatherings and instructing people to stay at home except for essential journeys and work.

Isolation and social distancing measures appear to be effective in controlling the pandemic13. Unfortunately they come at an enormous cost to people’s livelihoods, education and mental health, as well as to the global economy14. Adherence to isolation and social distancing behaviours faces strong practical, motivational and social barriers and also imposes considerable costs on people and society. These costs are borne disproportionately by people who are already disadvantaged15. Moreover, until and unless an effective vaccine can be found, a resurgence of infection is likely when these measures are relaxed. Widespread and rigorous adherence to ‘personal protective behaviours’ (individual behaviours aimed at protecting oneself and others) as set out in Fig. 1 is required. These behaviours are also needed to protect people who have to put themselves at risk of catching the disease in the course of vital functions they perform in society.

The biomechanics of transmission mean that it could be reduced at source by the infected person making sure that they cough or sneeze into a tissue that is immediately disposed of in a way that does not cause further contamination (Box 1 in Fig. 1). Face masks (Box 2 in Fig. 1) can act as a physical barrier to the spread of droplets, but their effectiveness in reducing virus transmission may be offset by people failing to use them appropriately, and what limited evidence is available as of the end of April 2020 has not clearly shown a benefit in community settings16.

Physical distancing (Box 3 in Fig. 1) aims to minimise the risk of direct transmission of the virus via inhaled droplets. The distance at which people are thought to be at risk from direct inhalation of contaminated droplets in normal circumstances is currently estimated at up to 2 m (ref. 17). However, it has been suggested that under certain conditions droplets or aerosol may travel further than this18.

Given the importance of fomites in transmission of the virus19, washing hands with soap or hand sanitiser (Box 4 in Fig. 1) and disinfecting objects and surfaces (fomites) (Box 5 in Fig. 1) may substantially reduce transmission. Transmission by fomites occurs because people touch their T-zone after touching them. The fomite route to transmission of the virus could be particularly important because the virus can survive on some surfaces for several days20. Therefore, not touching the T-zone (Box 6 in Fig. 1) may be an important behaviour to target. Although the above personal protective behaviours are included in government advice in a number of countries21,22,23, little guidance, training or support is given to promote adherence, even though failure to do so is critical to the transmission of the virus.

Understanding behaviour and how to change it

Ideally we would be able to draw on high-quality intervention evaluations to identify ways to increase enactment of personal protective behaviours. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of studies on this. There are some suggestions on how best to promote adherence to social distancing, for example5. While a considerable amount of research has been undertaken on hand-hygiene in certain settings24,25,26, generalisability to community settings is limited. We could find no published evaluations of interventions to reduce T-zone touching. There is some research on psychological interventions to reduce itch scratching in people suffering from atopic dermatitis, but no firm conclusions have been reached27,28.

In the absence of strong direct evidence to guide interventions, we can draw on behaviour-change principles to generate ideas as to what strategies to adopt. A staged process has been proposed for doing this, known as the ‘behaviour change wheel’29,30,31. This was derived from a synthesis of 19 major behaviour-change frameworks. It starts with an analysis of the capability, opportunity and motivation required to enact each behaviour. This is followed by mapping these requirements to relevant types of intervention (education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modelling and enablement) and types of policies best suited to delivering these (communications and marketing, guidelines, service provision, fiscal measures, regulation, legislation, environmental and social planning). This can then form a basis for a detailed specification of an intervention strategy and its proposed implementation, including the specific behaviour change techniques to use32. Throughout this process it is important to evaluate the options in terms of acceptability, practicability, effectiveness, affordability, spill-over effects, and equity (APEASE criteria29,31). All available evidence, direct and indirect, should be brought to bear on this evaluation.

Thus, the first stage in the process involves undertaking what has been termed a ‘behavioural diagnosis’ using the capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B) model29,30. Figure 2 shows a formal representation of the model, outlining how the different components relate to each other.

The capability–opportunity–motivation–behaviour (COM-B) model. Reproduced from ref. 48. Capability is an attribute of a person that together with opportunity makes a behaviour possible or facilitates it. Opportunity is an attribute of an environmental system that together with capability makes a behaviour possible or facilitates it. Motivation is an aggregate of mental processes that energise and direct behaviour. Behaviour is individual human activity that involves co-ordinated contraction of striated muscles controlled by the brain. Physical capability is capability that involves a person's physique and musculoskeletal functioning (e.g., balance and dexterity). Psychological capability is capability that involves a person's mental functioning (e.g., understanding and memory). Reflective motivation is motivation that involves conscious thought processes (e.g., plans and evaluations). Automatic motivation is motivation that involves habitual, instinctive, drive-related and affective processes (e.g., desires and habits). Physical opportunity is opportunity that involves inanimate parts of the environmental system and time (e.g., financial and material resources). Social opportunity is opportunity that involves other people and organisations (e.g., culture and social norms).

A principal tenet of the model is the common-sense idea that, at any given time, a behaviour occurs when both the capability and opportunity are present and when the person is more motivated to enact that behaviour than any other. A second key tenet is that capability, motivation, opportunity and behaviour are causally linked to each other in feedback loops, so that increasing capability or opportunity can influence motivation, and that behaviours feed back to influence opportunity, capability and motivation.

The motivational part of COM-B is elaborated in the PRIME theory of motivation33 (Fig. 3). This recognises that any behaviour can be influenced by both reflective and automatic processes. It proposes that these do not operate in parallel but rather that the proximal cause of all behaviour is always the balance between potentially competing impulses and inhibitions.

The processes involved in human motivation according to PRIME theory. Arrows denote the ‘influence’ relationship. Reproduced from ref. 48.

Potentially competing impulses and inhibitions are controlled by instinct and habit processes, plus any motives (wants or needs) that are present at the time. Wants and needs are generated by feelings of anticipated pleasure or satisfaction and of anticipated relief from discomfort or drive states. All of this makes up our ‘automatic’ motivation.

As humans we have the capacity to think about what we do and make conscious decisions—what may be termed ‘reflective motivation’. So, apart from wants and needs, there are thought processes that create and compare evaluations: beliefs about what is beneficial or harmful and right or wrong. These processes underlie our conscious decision-making, when we weigh up the costs and benefits of courses of action or work out solutions to problems. We also have the capacity to plan ahead, and these plans form much of the structure of our behaviour over the course of minutes, hours, days, weeks and years.

PRIME theory also recognises the importance of identity: the aggregate of our beliefs and the images of ourselves as we are, have been or could be, with the feelings attached to these34. These can be so strong that they even override need for survival. Finally, PRIME theory recognises the importance of imitation and modelling in human behaviour35. This occurs at the level of small-scale behaviours and mannerisms (for example, face touching) as well as much larger-scale behaviours, evaluations and wants and needs. It should also be noted that wants and needs influence evaluations. A well-recognised example is what has been termed ‘wishful thinking’36.

PRIME theory is not a replacement for more specific models that focus on particular motivational processes, but rather a way of linking them together. Of the more specific models, many are relevant to understanding behaviours that can block the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. A compendium of behaviour-change models has been put together that can help identify ones that may be relevant in any given situation37. These can be supplemented by models that focus on conscious decision-making processes (for example, ref. 38), on emotional and habit processes (for example, ref. 39) or on environmental influences (for example, ref. 40).

The main tenets of PRIME theory and examples of more specific models are summarised in Table 1. There are many others that are potentially relevant, but those chosen cover key principles to consider. Table 1 also gives examples of possible implications of the models for interventions to promote personal protective behaviours.

The principles described in Table 1 can help us begin to map out what is required in terms of capability, opportunity and motivation for each of the behaviours identified in Fig. 1. Table 2 provides a preliminary behavioural diagnosis for each of the protective behaviours, taking as read that they will all be enabled by having a ‘mental model’ of transmission routes and the ways in which the behaviours block these routes41.

In general, the capability to undertake personal protective behaviours requires people to understand what needs to be done, under what precise circumstances it needs to be done, how to do it and why it is important. It also requires development of appropriate skills and techniques. Opportunity requires ensuring access to the living and working arrangements, tools and resources that enable the behaviours to be enacted and, crucially, to maintain normal life as far as possible despite these behaviours. It also involves creating the social opportunity to support the behaviours, including norms and social rules. Motivation involves, at a minimum, people feeling a strong need to enact the behaviours in all the circumstances in which they are required, and this must be sufficient to overcome competing wants or needs in the moment. People should see the behaviour being enacted as valued within the group or groups they identify with and see other people enacting them. People need to develop rules and habits to sustain the behaviour. There will be large differences between people and between groups of people (for example, by personality, age, employment status and type of neighbourhood) in their capability, opportunity and motivation.

Interventions to promote behaviours to limit virus transmission

As noted earlier, the behaviour change wheel sets out nine broad categories of intervention that can be included in any behaviour change strategy: education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, enablement, training, restriction, environmental restructuring and modelling29,30,31. It also specifies criteria for evaluating intervention options. Table 3 summarises these criteria. Thus an intervention may be likely to be effective but to have unacceptable spill-over effects, or it may be impracticable or unacceptable to key stakeholders. An example of applying this approach to reducing COVID-19 transmission can be seen in a behavioural science paper presented to UK’s Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies outlining intervention options for increasing adherence to social distancing measures and consideration of them using the APEASE criteria42.

We applied the principles in Table 1 to the behaviours in Table 2 and evaluated these using criteria in Table 3. This led to a set of illustrative recommendations, as set out in Table 4. It must be emphasised that this is a preliminary analysis, and for formal recommendations, a much fuller and more systematic analysis would be required using the principles set out in the behaviour change wheel guide29,31.

Based on this preliminary analysis, different personal protective behaviours appear to require different types of intervention. Education is important, but unlikely to be sufficient. Persuasion and modelling will likely be crucial in motivating people to enact many of the behaviours. Use of social incentives and supportive and carefully applied coercive interventions will also presumably be important in some cases. Less obviously, training and various forms of enablement will likely be required to support some of the behaviours. Environmental restructuring will probably have a crucial role to play, in terms of the physical environment, provision of financial and material resources, and ensuring that social rules and norms are supportive of the required behaviours. It seems likely that mass media, social media and online platforms will be key to delivering interventions to promote personal protective behaviours. These will probably need to be supplemented by service provision by key workers in certain cases. Regulation and environmental planning may be needed in some cases, as will legislation.

Of the personal protective behaviours, one that may merit particular attention is not touching the T-zone. This is because the potential impact may be high if it can be achieved, it requires no additional facilities and appears to have no negative spill-over effects. The key question is whether effective interventions can be found to achieve this43. Combating the habit element could, for example, involve training conflicting habits (such as keeping hands below shoulder level), creating physical or behavioural barriers, or generating mindfulness to bring the behaviour to awareness before it is completed43,44. Training people not to touch their T-zone could be delivered, for example, by an online application using artificial intelligence to provide feedback on behaviours detected by webcams. Tackling what is probably the other primary driver, a feeling of need to scratch an itch, could involve techniques falling under the acronym DEADS: delay, escape, avoid, distract, substitute45.

Finding workable solutions will require not touching the T-zone to be considered much more seriously than it appears to be at the moment. This may be because it seems hard to imagine that a behaviour as trivial as this could make a difference in addressing such a huge crisis as a global pandemic. This could be an example of a yet-undocumented (to our knowledge) cognitive heuristic: what one might call the ‘proportionality heuristic’: a tendency to assume that the perceived magnitude of a solution to a problem should be proportionate to the magnitude of the problem.

Conclusions

In addition to isolation and social distancing measures, enactment of key personal protective behaviours is vital in order to reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses. Interventions to target individual behaviours such as these could potentially lead to substantial population-level effects46, and behavioural science models and methods can be used to develop and evaluate such interventions. There is currently a dearth of evidence on interventions to achieve these behaviour changes and an urgent need to rectify this. Given the urgency of the current situation, there may be merit in establishing an online hub for helping with the design of pragmatic evaluations, piloting of interventions, and rapid reporting of experiences and outcomes using a standardised approach.

References

Bradley, D.T., Mansouri, M.A., Kee, F. & Garcia, L.M.T. A systems approach to preventing and responding to COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100325 (2020).

Lunn, P. et al. Using behavioural science to help fight the coronavirus. J. Behav. Pub. Admin. 3, https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.31.147 (2020).

Scientific Pandemic Influenza behaviour Advisory Committee (SPI-B). The role of behavioural science in the coronavirus outbreak. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/873732/07-role-of-behavioural-science-in-the-coronavirus-outbreak.pdf (SAGE, 2020).

Behavioural Science and Disease Prevention Taskforce. Behavioural science and disease prevention: psychological guidance. https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/www.bps.org.uk/files/Policy/Policy%20-%20Files/Behavioural%20science%20and%20disease%20prevention%20-%20Psychological%20guidance%20for%20optimising%20policies%20and%20communication.pdf (British Psychological Society, 2020).

Van Bavel, J.J. et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z (2020).

Taylor, S. The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019).

Shah, H. Global problems need social science. Nature 577, 295 (2020).

Lake, M. A. What we know so far: COVID-19 current clinical knowledge and research. Clin. Med. (Lond.) 20, 124–127 (2020).

NHS. NHS Advice on stopping spread of COVID-19 https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/ (2020).

Lu, J. et al. COVID-19 outbreak associated with air conditioning in restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200764 (2020).

World Health Organisation. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations (WHO, 2020).

Lewis, D. Is the coronavirus airborne? Experts can’t agree. Nature 580, 175 (2020).

Cowling, B. J. et al. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Public Health https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6 (2020).

Alegado, S. Global Cost of Coronavirus May Reach $4.1 Trillion, ADB Says. Bloomberg https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-03/global-cost-of-coronavirus-could-reach-4-1-trillion-adb-says (2 April 2020).

Brooks, S. K. et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920 (2020).

Feng, S. et al. Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir. Med. S2213-2600(20)30134-X (2020).

Service, R. You may be able to spread coronavirus just by breathing, new report finds. Science https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/you-may-be-able-spread-coronavirus-just-breathing-new-report-finds# (2 April 2020).

Bourouiba, L. Turbulent gas clouds and respiratory pathogen emissions: potential implications for reducing transmission of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4756 (2020).

Boone, S. A. & Gerba, C. P. Significance of fomites in the spread of respiratory and enteric viral disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1687–1696 (2007).

van Doremalen, N. et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1564–1567 (2020).

National Health Service. Advice for everyone: Coronavirus. (COVID-19) https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/ (2020).

Australian Department of Health. How to protect yourself and others from coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/how-to-protect-yourself-and-others-from-coronavirus-covid-19 (2020).

Government of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) prevention and risks. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/prevention-risks.html (2020).

Mbakaya, B. C., Lee, P. H. & Lee, R. L. Hand hygiene intervention strategies to reduce diarrhoea and respiratory infections among schoolchildren in developing countries: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 371 (2017).

Doronina, O., Jones, D., Martello, M., Biron, A. & Lavoie-Tremblay, M. A systematic review on the effectiveness of interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance of nurses in the hospital setting. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 49, 143–152 (2017).

Schmidt, W.-P., Wloch, C., Biran, A., Curtis, V. & Mangtani, P. Formative research on the feasibility of hygiene interventions for influenza control in UK primary schools. BMC Public Health 9, 390 (2009).

Chida, Y., Steptoe, A., Hirakawa, N., Sudo, N. & Kubo, C. The effects of psychological intervention on atopic dermatitis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 144, 1–9 (2007).

Hashimoto, K., Ogawa, Y., Takeshima, N. & Furukawa, T. A. Psychological and educational interventions for atopic dermatitis in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Change 34, 48–65 (2017).

Michie, S., Atkins, L. & West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions (Silverback Publishing, 2014).

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 6, 42 (2011).

West, R., Michie, S., Atkins, L., Chadwick, P. & Lorencatto, F. Achieving Behaviour Change: A Guide for Local Government and Partners (Public Health England, 2020).

Michie, S. et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 46, 81–95 (2013).

West, R. & Brown, J. Theory of Addiction (Wiley, 2013).

Hornsey, M. J. Social identity theory and self‐categorization theory: a historical review. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2, 204–222 (2008).

Davis, J.M. in Perspectives in Ethology (eds Bateson, P. P. G. & Klopfer, P. H.) 43–72 (Springer, 1973).

Mayraz, G. Wishful thinking. SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1955644 (2011).

Michie, S., West, R., Campbell, R., Brown, J. & Gainforth, H. ABC of Behaviour Change Theories (Silverback Publishing, 2014).

Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertain. 5, 297–323 (1992).

Bouton, M.E. Learning and Behavior: A Contemporary Synthesis. (Sinauer Associates, 2007).

Kahneman, D. & Miller, D. T. Norm theory: Comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychol. Rev. 93, 136–153 (1986).

Diefenbach, M. A. & Leventhal, H. The common-sense model of illness representation: Theoretical and practical considerations. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 5, 11–38 (1996).

Michie, S., et al. Reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the UK: a behavioural science approach to identifying options for increasing adherence to social distancing and shielding vulnerable people. Br. J. Health Psychol. (in the press).

Hallsworth, M. How to stop touching our faces in the wake of the Coronavirus. The Behavioural Insights Team https://www.bi.team/blogs/how-to-stop-touching-our-faces-in-the-wake-of-the-coronavirus/ (5 May 2020).

Clark, F., Sanders, K., Carlson, M., Blanche, E. & Jackson, J. Synthesis of habit theory. OTJR (Thorofare, N.J.) 27, 7S–23S (2007).

West, R., Michie, S., Rubin, G.J. & Amlot, R. Don't touch the T-zone. BMJO Opinion https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/04/03/dont-touch-the-t-zone-how-to-block-a-key-pathway-to-infection-with-sars-cov-2/ (3 April 2020).

Sniehotta, F. F. et al. Complex systems and individual-level approaches to population health: a false dichotomy? Lancet. Public Health 2, e396–e397 (2017).

West, R. & Michie, S. Routes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and behaviours to block it: a summary. Qeios https://doi.org/10.32388/F6M5CB (2020).

West, R. & Michie, S. A brief introduction to the COM-B model of behaviour and the PRIME theory of motivation. Qeios https://www.qeios.com/read/article/564 (2020).

Janis, I.L. & Mann, L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment (Free Press, 1977).

Greenwald, A. G. & Ronis, D. L. Twenty years of cognitive dissonance: case study of the evolution of a theory. Psychol. Rev. 85, 53–57 (1978).

van den Bos, W. & McClure, S. M. Towards a general model of temporal discounting. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 99, 58–73 (2013).

McCrae, R. R. & Costa Jr, P. T. The five-factor theory of personality. in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (eds John, O. P., Robins, R. W. & Pervin, L. A.) 159–181 (Guilford Press, 2008).

Acknowledgements

G.J.R. and R.A. are affiliated with the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London, in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with the University of East Anglia. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Editor recognition statement: Primary handling editor: Stavroula Kousta

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

West, R., Michie, S., Rubin, G.J. et al. Applying principles of behaviour change to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nat Hum Behav 4, 451–459 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0887-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0887-9

This article is cited by

-

Behavioural Sciences Contribution to Suppressing Transmission of Covid-19 in the UK: A Systematic Literature Review

International Journal of Behavioral Medicine (2024)

-

Pathology of life in the Coronavirus-stricken world: a re-analysis of Sadraean practical theology

Contemporary Islam (2024)

-

Rethinking the city resilience: COM-B model-based analysis of healthcare accessing behaviour changes affected by COVID-19

Journal of Housing and the Built Environment (2024)

-

The problem is obtaining knowledge: a qualitative analysis of provider barriers and accelerators to rapid adoption of new treatment in a public health emergency

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Association between COVID-19 risk-mitigation behaviors and specific mental disorders in youth

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health (2023)