Abstract

Affective polarization has become a defining feature of twenty-first-century US politics, but we do not know how it relates to citizens’ policy opinions. Answering this question has fundamental implications not only for understanding the political consequences of polarization, but also for understanding how citizens form preferences. Under most political circumstances, this is a difficult question to answer, but the novel coronavirus pandemic allows us to understand how partisan animus contributes to opinion formation. Using a two-wave panel that spans the outbreak of COVID-19, we find a strong association between citizens’ levels of partisan animosity and their attitudes about the pandemic, as well as the actions they take in response to it. This relationship, however, is more muted in areas with severe outbreaks of the disease. Our results make clear that narrowing of issue divides requires not only policy discourse but also addressing affective partisan hostility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The rise of affective polarization—most notably, the tendency for partisans to dislike and distrust those from the other party1—is one of the most striking developments of twenty-first-century US politics2,3. Affective polarization has wide-ranging implications for our social and economic lives. It plays a role in how much time we spend with our families, where we want to work and shop and whom we want to date and marry4. But what does it mean for our politics? The answer is surprisingly unclear, as Iyengar and colleagues note (p. 139): “little has been written on this topic (that is, the political effects), as most studies have focused on the more surprising apolitical ramifications”4. Here, we take up a crucial dimension of that question: how are individuals’ issue positions related to their level of affective polarization?

We argue that the two are strongly connected in ways not addressed in previous research. Partisans with high levels of animus toward the other party are more motivated to distinguish themselves from their political opponents. They do so by taking positions on new issues that differ from the other (disliked) party and match those of their own preferred party. While this argument—that previous levels of partisan animus play a role in subsequent issue positions—is straightforward, testing it is difficult given the inherent endogeneity between policy beliefs, affective polarization and elite issue positions: if scholars find that those who harbour the most animus toward the other party also hold more extreme beliefs, is that due to animus driving those particular beliefs, to policy beliefs driving animus5 or due to elite issue polarization simultaneously driving both the public’s out-party animus6 and policy beliefs7?

The emergence of the novel COVID-19 pandemic in the winter of 2020 presents us with the conditions needed to overcome some of the endogeneity that limits existing work. We collected data on respondents’ levels of affective polarization in 2019, before the emergence of the coronavirus. We therefore have a measure of affective polarization that is exogenous to the pandemic: we can examine how pre-existing levels of partisan animus correlate with subsequent responses to COVID-19 without concern that the responses to the pandemic are, in fact, shaping affective polarization (and, more directly, out-party animus). Put another way, this design allows us to rule out the aforementioned possibilities that individuals’ or elites’ policy beliefs drive affective polarization (and hence any relationships between polarization and beliefs). Although our approach cannot isolate causal effects—given that we use observational data without a clear causal identification strategy—it does allow us to overcome the endogeneity identified above, which has been the key limitation encountered in previous work.

We find a strong association between out-party animus and subsequent responses to the pandemic, offering evidence that policy beliefs reflect affective feelings toward the other party rather than just the issues at hand. That said, however, our findings also highlight how local context matters, as this relationship is muted among those who live in areas with particularly severe outbreaks of COVID-19. In these locations, even those with high levels of partisan animus have good reason to be concerned about the virus—it is personally salient to them. This highlights how real-world conditions affect citizens’ issue positions, and suggests a potential limit to the types of partisan-motivated reasoning that probably underlie our results. The implications of our work go beyond political ramifications; we demonstrate that partisan hostility combined with conflicting elite cues can intersect with national efforts and can, quite literally, mean the difference between life and death8.

To explicate our argument, we start conceptually by connecting affective polarization with partisanship1. Partisanship is a type of social identity and, by identifying with one party, individuals divide the world into two groups: their liked in-group (our own party) and a disliked out-group (the other party)9. This process gives rise to two of the underlying components of affective polarization: in-group favouritism and out-group animosity4.

Over-time shifts in affinity for one’s own party and animosity toward the other party have not been symmetric2,4,10,11. Indeed, out-party animus has increased dramatically in recent years2,4 while in-party warmth has, if anything, slightly declined over the same time period10. Consistent with evidence of increasing out-party animosity, individuals report that they are less likely to date those from the other party12, they would pay out-partisans less for the same work13 and they would prefer not to have out-partisans as roommates14. Furthermore, those with higher levels of out-party animosity report engaging in more discriminatory behaviour against those from the other party (for example, they do not want to work with those from the other party)15. Out-party animus, rather than in-party favouritism, is key to these associations in the literature11.

Partisan identity alone, however, is not enough to explain out-group animus2,16—one must also account for other changes in the political and media environment2,4. The partisan-ideological sorting of liberals to the Democratic Party and conservatives to the Republican Party7, as well as the social sorting that has led to more demographically homogenous parties17, have both contributed to partisan animosity. Also at work are other changes in elite behaviours18 and increasing elite polarization6,19. Moreover, changes in the information environment, such as the rise of partisan media20,21, increasingly negative campaigns22 and new social media outlets, contribute to out-party animosity23.

Given that out-party animus has elevated the partisan cue in social contexts, it may also have affected people’s responses to elite political cues. As Pierce and Lau argue, for example (p. 9), “strong affective reactions to a politician may themselves engender awareness of and like or dislike for certain policies. For instance, a visceral aversion to a candidate may lead a voter to reject positions associated with that politician”24. To this end, people are motivated to do the opposite of what the other, disliked, party endorses25,26,27. They do this because the out-party animus is so strong that they want to differentiate themselves from that disliked party. And, importantly, it follows that those with greater out-party animus (that is, stronger affective reactions) will be most motived to hold distinctive views28,29, taking positions opposite to those put forth by out-party elites (for example, elected officials) and in line with those of their own party’s elites. This response to cues may be especially apparent when the difference between in-party and out-party cues is stark30, as it is in the case of COVID-19 (refs. 31,32).

Demonstrating that affective polarization (and its key underlying component, out-party animus) relates to policy beliefs, however, is surprisingly complicated33. There is an empirical relationship between alignment in issue positions and partisan animus but it is difficult to identify the original source of this relationship34. Indeed, theoretically, the relationship between issue beliefs and out-party animus could stem from three possible scenarios: (1) animus driving cue taking on issues (as just explained), (2) issue position extremity causing greater partisan animus5,34 or (3) elite issue polarization leading separately to both public issue divides7 and out-party animus among the public6,35. As a result, it is difficult to determine how animus connects to political views—that is, whether policy positions are undergirded by affective dislike beyond substantive considerations.

Although it is difficult to address this issue fully without manipulating affective polarization, one approach that would allow us to address a part of this problem is a measure of out-party animus taken before the emergence of an issue. This allows us to record levels of animus (at time t – 1) before the existence of those issue positions (at time t). This means that elite polarization on the issue at time t cannot have affected earlier measures of partisan animus taken at time t – 1, or that attitudes measured at time t are the cause of this time t – 1 animus. Nevertheless, the persistence of existing issues on the policy agenda, and the unpredictability of new issues emerging onto the agenda, make it extremely difficult to use an ex ante measure (and, to our knowledge, this has not been done). The COVID-19 pandemic, however, allows us to consider an issue as it emerges.

To do this, we need measures of partisan animus taken before COVID-19 began to spread in the United States. If we instead used a measure taken after COVID-19 entered the agenda, the issue itself—and politicians’ reactions to it—could shape those recorded levels of partisan animus. For example, Democrats’ levels of partisan animus might reflect not only their underlying hostility toward President Trump, but also how he specifically responded to COVID-19 (that is, downplaying its severity, refusing to acknowledge its existence in the United States for several weeks, and so on). If we see that this measure of animus is related to attitudes about the pandemic, then, it could simply reflect politicians’ reactions to it. We therefore use pre-pandemic measures of partisan animus (from August 2019)—paired with attitudes toward the pandemic measured once it emerged (from April 2020)—to study the relationship between the two.

The partisan difference in elite responses to the pandemic suggests why affective polarization, and specifically out-party animus, may play a key role in driving issue positions here. From the beginning of the outbreak, Democratic politicians, relative to Republican ones, expressed greater concern about the virus, implored the public to take more precautions and supported more restrictive policies36. President Trump—with his dismissal of the virus, demands to reopen the economy and refusal to wear a mask—is the apotheosis of this trend, but is far from the only example of it, as Democratic governors typically took swifter and more public actions to combat the virus than did most Republican governors37. Moreover, these partisan debates and polarization on the issue were reflected in the media coverage38. The fact that the two parties behaved as mirror opposites in response to the pandemic is especially notable here, as it means that citizens simultaneously received distinct information about how members of both partisan groups should behave, making the elite cues especially clear7. This makes for clear cues, but it also means we cannot empirically differentiate the relative impact of in-party versus out-party cues. Future work would benefit from looking at situations with cues from only one party32, although it is a situation that is increasingly rare39. We would expect that, in such situations, animus would drive reactions from the out-party cue alone and (possibly) the in-party cue alone since partisans want to distinguish themselves.

In line with the aforementioned theoretic logic that affective polarization—and especially its key ingredient, out-party partisan animus—may increase the motivation to follow cues, we expect the following pattern: as out-party animus increases, Democrats will express more concern about the virus, be more willing to take actions to prevent its spread (for example, wash their hands more, avoid large crowds, cancel travel and so on) and be more supportive of policies to stop the virus (for example, stay-at-home orders) (hypothesis 1a). Conversely, among Republicans we expect that as out-party animus increases, worries about COVID-19 will decrease, there will be a lower likelihood of taking actions to prevent its spread and less support for policies to stop the spread of the virus (hypothesis 1b). Our argument is not simply that partisan gaps have emerged: that point has been thoroughly documented elsewhere8,40,41. Instead, our argument is that it is the animus component of affective polarization, at least partially, that drives these gaps.

Our argument implicitly invokes partisan-motivated reasoning since we posit that partisans have a directional motivation in forming opinions42. Partisan-motivated reasoning means partisans process information and form attitudes with the goal of confirming their partisan identities and differentiating themselves from the other party (this contrasts with issue-based motivated reasoning where the goal is to confirm a standing issue belief)43. While directional partisan reasoning predominates in highly political situations44, it can shift when particular issues rise in salience45. Of particular relevance are conditions that prompt partisans to shift from having a directional motivation to an accuracy motivation. In this latter case, individuals assess information based on the ‘best’ available evidence rather than to affirm an identity46,47,48.

In the case of COVID-19, this will occur as the direct threat of the virus increases and is captured by the number of cases in one’s local area. An increase in cases can alter personal experiences (for example, increasing the likelihood that someone you know personally has been infected) which, in turn, vitiates partisan reasoning47. We thus predict that, as the number of COVID-19 cases in one’s area increases, the impact of out-party animus will decrease and the partisan gap will similarly decrease (hypothesis 2). In short, partisan animus matters, but so too does the geography of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Broadly, then, our study suggests the possibility that partisan-motivated reasoning is conditional and may be shaped by context. Following a similar logic, we also might expect the partisan animus effect to decline among those who have had, or are vulnerable to, COVID-19, but at the time of our data collection the number of such individuals in our sample was too small to test that possibility.

We use a multi-wave, nationally representative survey. In the summer of 2019, 3,345 respondents answered a set of questions (for an unrelated survey) that provide our pre-COVID-19 measure of partisan animosity. These participants were re-interviewed in April 2020 as the coronavirus spread throughout the nation; a total of 2,484 respondents who answered our 2019 questionnaire completed our re-interview, for a re-contact rate of 74% (more details on the sample are given in Supplementary Methods). In this re-interview, we measured participant reactions to the COVID-19 outbreak focusing on three relevant dimensions: (1) how worried they are about the virus, both for themselves and for the nation as a whole, measured by a range of items assembled into an index (α = 0.89); (2) which behaviours (from a list of 14) they are taking to avoid becoming infected with COVID-19 (that is, washing their hands more, cancelling travel and so on); and (3) their support for various policies to limit the spread of COVID-19 (that is, stay-at-home orders, business closures and so on), again analysed as an index (α = 0.73). All analyses treat these three measures as dependent variables, and the pre-pandemic measure of animosity is our key explanatory variable. More information on the survey is provided in Methods and Supplementary Methods.

Results

Figure 1 shows kernel density plots (separately for Democrats and Republicans) for each of the three dependent variables: (1) worry about COVID-19, (2) behaviours being taken to avoid becoming infected with COVID-19 and (3) support for various policies to limit the spread of COVID-19; see Methods for details on the coding of these and all other variables.

The plots show that the average Democrat is more worried, is more likely to have changed behaviours and is more supportive of polices to stop the spread of infections than the average Republican, consistent with other analyses showing partisan gaps in these areas40,41. There is, however, substantial overlap in the attitudes of Republicans and Democrats, which suggests the possibility that something moderates the relationship between partisanship and COVID-19 attitudes.

Figure 2 contains scatter plots for each of the dependent variables (on the y axes) along with the number of cases in the respondent’s county (on the x axes), as well as a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) smoother to show the nonparametric bivariate relationship between the two variables. It is clear that, as case numbers increase, values on all dependent variables also increase. Because the relationship is nonlinear, especially for low-infection areas, and there is a long right-tail of cases (that is, a small number of areas, primarily in New York City, with extremely high rates of infection), we use the natural log of cases in all of our models.

We next turn to our quantities of interest—the relationship between partisanship, partisan animosity and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic—and estimates of uncertainty around those effects. To ensure the robustness of our results, we estimate a series of models with additional controls added in each model (Methods and Supplementary Methods). The results we present are robust to changes in estimation approach, and to the inclusion of a variety of controls including a measure of partisan affect and strength of identity.

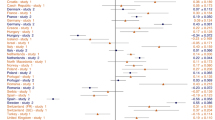

We present the results of our main models in Figs. 3–7. These are represented as plots since our models rely on interactions, and the coefficient estimates on interactions and their constitutive terms do not easily translate to our quantities of interest; as a result, the significance levels of these coefficients may not be informative in terms of testing our hypotheses49,50,51. Relevant here is the slope of the outcome variable at various levels of other covariates, a quantity termed the ‘marginal effect’; this term is not intended to signal a causal relationship52. By definition, all tests of the statistical significance of this effect are two-tailed.

Top: the marginal effect of partisan animosity for Democrats and Republicans; bottom: the effect of Republican partisanship for different levels of partisan animosity; left: the effects on worry about COVID-19; middle: the effects on changes in behaviour; right: the effects on support for COVID-19 policies. For worry about COVID-19, results are from from OLS model 1 in Supplementary Table 9 (n = 2,062); for changes in behaviour, results are from OLS model 1 in Supplementary Table 10 (n = 2,066); for support for COVID-19 policies, results are from OLS model 1 in Supplementary Table 11 (n = 2,064). Thicker lines represent 90% confidence intervals, with thinner lines indicating 95% confidence intervals.

Results from OLS model 6 in Supplementary Table 9 (n = 2,003). Light-grey-shaded areas represent 90% confidence intervals, with darker grey areas indicating 95% confidence intervals.

Results from OLS model 6 in Supplementary Table 10 (n = 2,006). Light-grey-shaded areas represent 90% confidence intervals, with darker grey areas indicating 95% confidence intervals.

Results from OLS model 6 in Supplementary Table 11 (n = 2,005). Light-grey-shaded areas represent 90% confidence intervals, with darker grey areas indicating 95% confidence intervals.

For worry about COVID-19, results are from OLS model 6 in Supplementary Table 9 (n = 2,003); for changes in behaviour, results are from OLS model 6 in Supplementary Table 10 (n = 2,006); for support for COVID-19 policies, results are from OLS model 6 in Supplementary Table 11 (n = 2,005). Thicker lines represent 90% confidence intervals, with thinner lines indicating 95% confidence intervals.

We begin with plots from a model that includes an interaction between partisanship and partisan animosity, while controlling for the number of cases. The top panels of Fig. 3 present the marginal effect of out-party animus for Democrats and Republicans for each dependent variable, while the bottom panels show the marginal effect of Republican partisanship for various levels of animus. Hence, the top parts directly test hypotheses 1a and 1b for each dependent variable, while the bottom parts plot the partisan gap as out-party animus increases.

Beginning with worry, we see a decline in worry about COVID-19 among Republicans as out-party animus increases but we do not see a similar relationship between partisan animus and how worried Democrats are about COVID-19. When we move to the middle panels of Fig. 3 examining behaviours, here we see that Democrats with high levels of animus report engaging in more behaviours to combat COVID-19 than do Democrats who do not hold as much animus. With this dependent variable, however, there is no similar, statistically significant result among Republicans. Finally, with regards to policy, we see that out-party animus is associated with greater support for policies to combat COVID-19 among Democrats while Republicans with high levels of animus are less supportive of the same policies than Republicans with less animus. Hence we see support for the partisan animus hypothesis for at least one party across all three variables.

As the bottom panels of Fig. 3 show, there is a partisan gap for each dependent variable and the size of that gap grows as out-party animus increases. Since the model controls for the number of cases in the respondent’s county, the partisan gaps are not the result of areas with many Democrats having more severe outbreaks than areas with many Republicans. Recall, however, we argue that severe outbreaks might mitigate the role of partisan animosity. The figures now described will look at the models with triple interaction, including cases.

In Figs. 4–6, we present the marginal effect of the Republican dummy variable at different levels of out-party animus—that is, the difference in the expected value in the dependent variable for Republicans minus the expected value in the dependent variable for Democrats. For each dependent variable, we include separate plots for a low number of cases (the 25th percentile) and a high number of cases (the 75th percentile). If our argument is correct, then we should find that as out-party animus increases, the gap between the parties increases as well (that is, the marginal effect of partisanship increases; this is the test of hypothesis 1). However, we should also find that this relationship is muted in areas with large numbers of cases, as all citizens are more concerned about the virus. Simply put, we should see a steeper slope (larger marginal effect) in areas with low cases relative to high cases if hypothesis 2 is correct.

In Fig. 4 we present the marginal effect of being a Republican (as opposed to a Democrat) on worry, as partisan animus increases. In the left-hand panel, which presents the relationship between partisanship and out-party animus in areas with few cases, we see that as partisan animus increases, the partisan gap emerges: when animus is low, partisans are indistinguishable from one another but, when animus is high, partisans significantly diverge. In contrast, in the right-hand panel, depicting the pattern in areas with high levels of cases, there no significant partisan gap among those with high levels of animus (that is, the confidence interval overlaps zero). We do see small partisan differences for moderate levels of out-party animus (probably because the majority of our respondents have moderate levels of animus), but these gaps are distinctly smaller than the partisan gaps among those who live in areas with few cases.

Figure 5 presents the same analysis for the behaviour dependent variable. Partisan animus again has a clear correlation with political outcomes, as we observe partisan divides on COVID-19 behaviours. The difference, however, is that we see the same increasing partisan gap regardless of the number of cases in the county. Higher numbers of cases correlate with more preventative behaviours overall, but higher partisan gaps in behaviour emerge alongside animus regardless of the number of cases. The reason for this is that, while individuals with low or moderate levels of animus are responsive to the number of cases, Democrats and Republicans with high levels of animus are not.

Why do those with such animus not change their behaviour as the number of cases increases? The answer is probably different for Republicans and Democrats. Republicans with high animus took low-cost actions (for example, hand washing) in low-case areas and were forced to avoid certain behaviours (like going to restaurants) due to local restrictions. As cases increased, they may have believed they were already doing enough. Democrats with high levels of animus are probably less responsive because they are engaging in more behaviours even in counties with few cases. Nevertheless, because the group is already changing behaviours in low-case areas, they are unlikely (or perhaps, even unable) to take on more behaviours in areas with more severe outbreaks.

Turning next to Fig. 6, we see that when it comes to policy support there is once again a relationship between partisan animus and opinions. Here, much as with worry, the number of cases moderates the relationship. Although there is a significant partisan difference among partisans with high animus when cases are low, there is no statistically significant difference between Republicans and Democrats in those counties with high numbers of cases, regardless of the level of animus. We note that support for policies to prevent the spread of infections is high; among both Democrats and Republicans, a majority supported these policies at the time of the re-interview. As a result, it probably should not be a surprise that, in areas with a significant outbreak of COVID-19 infections, partisan gaps disappear. Otherwise, like worry but unlike behaviours, expressing policy support is not a costly behaviour per se. It is worth noting that Republicans with high animus and in high-case areas appear to be more supportive of government policy intervention than of engaging in relevant behaviours, and this is an area for future work to explore more carefully.

In Fig. 7, we use the same models to present a different perspective on the results, now focusing on the marginal effect of out-party animus for Democrats and Republicans in low- and high-case counties. The goal here is to see which party is the root of the partisan gaps at higher levels of partisan animus, by considering the relationship between a unit increase in animus and the likelihood of worrying, changing behaviour and supporting policy.

For worry about COVID-19 and support for COVID-19 policies, the marginal effect of animus is significant and negative for Republicans in counties with few cases; the confidence intervals for the other marginal effects overlap with zero. Increases in animus are statistically significant only for Republicans in counties with low cases, suggesting that, for worry and support, partisan gaps are largely a function of Republicans with considerable animus towards Democrats.

When it comes to behaviours, however, the only statistically significant marginal effect for partisan animus is among Democrats in counties with few cases—these individuals are engaging in preventative behaviours despite the low community spread of COVID-19. At the same time, however, in counties with large outbreaks, the absolute size of the marginal effects for both Democrats and Republicans is still equivalent to a full behaviour in both cases—even if the confidence intervals overlap zero. That might explain why the partisan gap remains in those counties: the difference within parties between those with high animus is smaller but, since the parties move in opposite directions, the partisan gap remains the same.

Overall, the results make clear that the partisan gaps observed in the data are at least partially a function of partisan animus, suggesting that it is cue taking that divides the parties on this issue. This type of partisan reasoning, however, is blunted when real-world threats become salient: in areas with substantial numbers of infections the role of animus is more muted, as all citizens respond to the outbreak.

Furthermore, we see that with regards to worry and policy support, the correlation with partisan animus in counties with low cases is most pronounced among Republicans. Given the messaging from the President, this pattern makes sense. It is understandable why Democrats, regardless of animus, and (to a lesser extent) Republicans who do not have high animus worried about the virus’s impact on public health and the economy, and supported shutdowns and stay-at-home orders even when the local severity was low. On the other hand, Republicans with high animus attuned to a Republican President saying, counter to the clear Democratic message, that it will all just disappear53, needed an active, local outbreak to increase their concerns to the level that Democrats were feeling.

Discussion

While scholars, pundits and citizens alike invoke affective polarization as a factor in driving issue positions, there has, to date, been no direct evidence that it actually does. We leveraged a unique data opportunity to track the association between affective polarization and, more directly, out-party animus and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Rhetorical differences between party elites help to produce our results: not only were Democratic elites much more likely to emphasize the threat of the virus to public health and the importance of taking appropriate precautions54, but President Trump downplayed the danger and advocated for treatment approaches shown to be ineffective55. Other Republican elected officials were similarly dismissive of the virus at the time of our study.

These rhetorical divisions are associated with mass partisan divisions: as animus increases, Republicans become less concerned about COVID-19 and less willing to support policies to mitigate the threat of the virus. Real-world threat—here, a high level of infections in one’s county—tempers that relationship, since, as theories of reasoning suggest, it pushes individuals away from directional partisan motivations towards an accuracy motivation—that is, a desire to rely on the best available evidence to which they have access. Still, we note that even in counties with high numbers of cases, Democrats and Republicans with high levels of animus differ in how likely they are to report engaging in actual, costly behaviours. This is because Democrats with high levels of out-party animus are already engaging in a high number of mitigating behaviours while Republicans with high levels of out-party animus remain resistant to costly behaviours as case levels increase.

These findings have implications for understanding how best to combat COVID-19. Since affective polarization (particularly partisan animus) underlies partisan gaps, policymakers will need to devise different strategies to bring the parties together on these issues. Simply highlighting areas of commonality, scientific directives or economic forecasts is not enough; instead, they will need to ameliorate partisan animus to shrink the gaps. This would require, for example, correcting misperceptions about the parties56,57, priming superordinate identities58 and/or fostering inter-party contact and dialogue59. The results also offer insights for theories of partisan reasoning, insofar as they show how such thinking can drive opinions but also how real-world threats can alter motivations.

More broadly, our findings suggest that policy differences between the parties are not simply a function of different information60,61, or different values62, but possibly of partisan animus as well. This is a substantial finding insofar as a large literature documents correlations between partisan animosity and social and economic behaviours (for example, on friendships, romantic relationships, business transactions and so forth)4, but there is much less work examining the association between animus and political attitudes, due to the data difficulties we highlighted earlier in the paper. We show clear political consequences with respect to perhaps the most important of policies: government directives for preventing a public health and economic crisis.

That we find these patterns in response to a global pandemic is notable. Months after our initial study, new polls showed a declining partisan gap on the use of masks; the closing of this gap was due to increasing mask use by Republicans63. These shifts in public behaviour follow changing rhetoric by Republican elites—including President Trump—to follow the Democratic perspective on mask wearing64,65. Our results offer a context to these shifts. If affective polarization—and, most importantly, partisan animus—is associated with greater responsiveness to party cues, then elite behaviours could have tremendous capacity to change mass response to the pandemic. In other words, the contrasting decisions made by Democratic and Republican elites during the early days of the pandemic may have carried profound implications for the spread of COVID-19 in the United States.

Methods

Measuring partisan animosity

The study followed all ethical guidelines and was reviewed by Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board and deemed to be exempt (no. STU00212339). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were offered remuneration for their time in accordance with the survey company’s agreement with participants. The data include measures of out-party animus taken before the emergence of COVID-19 in the United States, which occurred in early 2020. These measures are from a nationally representative survey conducted (for an unrelated study) in the summer of 2019. We provide details about the survey in Supplementary Methods. The key variables for our purposes are a large battery of items designed to tap out-party animus: feeling thermometer ratings of the other party (that is, on a scale of 0–100 how cold or warm partisans feel towards the other party), a trait battery (that is, how well terms like honest, intelligent, selfish and so on describe the other party), trust in the other party and a set of social distance items that measure how comfortable respondents are with interacting with those from the other party in various social settings66. As argued, our focus is on the out-party animus piece of affective polarization; however, we do, in additional analyses, account for in-party favouritism finding, much like in previous work, that it is out-party animus that plays the key role in the outcomes we observe.

A total of 3,345 respondents answered these questions, which provide our pre-COVID-19 measure of partisan animosity. We combine these four measures of out-party animus into an index (α = 0.88), rescaled to lie between 0 and 1 with higher values indicating increased levels of out-party animus. As in earlier work on similar topics66, we exclude pure Independents from our study but retain Independents who lean toward a party. The distribution of the variable by party is given in Supplementary Fig. 1; we also demonstrate that the variable is related to, but distinct from, in-party affect and the strength of partisan identity, in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5. Data analysis was not performed blind to the conditions (for example, number of cases in a given area), but the core analyses were preregistered before data collection at https://aspredicted.org/tp99f.pdf on 3 April 2020.

COVID-19-related variables

Once the coronavirus spread throughout the country and states began responding by shutting down their economies, we re-interviewed respondents in early to mid-April, 2020. We contacted all individuals who had answered our partisan animosity questionnaire in 2019, and thus the final sample size of 2,484 was determined by the 74% response rate to the re-interview. Just over 50% of the sample reported being female, and the median participant fell in the age range 35–50 years. We provide more details on our sample, including comparisons to census benchmarks, in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

In the re-interview survey we asked respondents about their reactions toward the COVID-19 outbreak, focusing on three relevant dimensions: (1) how worried they are about the virus, both for themselves and for the nation as a whole, measured by a range of items collated into an index (α = 0.89); (2) which behaviours (from a list of 14) they are taking to avoid becoming infected with COVID-19; and (3) their support for various policies to limit the spread of COVID-19, again analysed as an index (α = 0.73). The worry and policies variables are recoded to a scale of 0–1 while the behaviour variable is treated as a count. Full wording for all items is provided in Supplementary Methods with descriptive statistics for all variables (including all control variables). Also, the re-interview survey included one out-party animus item that was included in the earlier wave, asking respondents to rate the other party on the feeling thermometer scale. The correlation in out-party animus between the waves is 0.76, suggesting a high degree of over-time stability67.

To capture threat from the disease, we use counts of cases in each respondent’s county, as reported by The New York Times (https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data)—specifically, the 3-day moving average of cases. Since case counts are measured at the county level in the models including this variable, we cluster standard errors at the county level to account for this dependence in our data. Also, because cases and deaths are correlated at 0.99, using deaths as the measure of local outbreak severity yields substantively identical results.

Models of COVID-19 attitudes

Our hypotheses rely on a set of dependent variables—worry, behaviour and policy support—and three main independent variables: (1) a dummy variable for partisanship (coded 1 if the respondent is a Republican and 0 if the respondent is a Democrat); (2) the respondent’s level of out-party animus; and (3) the logged cases in the respondent’s county. We also control for the population of the respondent’s county (that is, a per-capita adjustment).

Our surveys included variables that shape partisan animosity including partisan identity strength, ideology, demographics (for example, gender, race and ethnic identity, income, education), exposure to partisan media (for example, Fox News, MSNBC) and elite leadership (for example, partisanship of the state governor, exposure to Trump press briefings). These and other measures such as age, other media exposure, cultural and economic issue attitudes and so on appeared in the first wave of the survey. The re-interview wave included measures of pre-existing health conditions relevant to COVID-19. We include all of these measures as control variables in our models; the full list of control items appears in Supplementary Methods. In the absence of a clear identification strategy, an observational analysis such as ours cannot claim to identify a causal effect but we note that we attempted to control for as many of the potential confounds as possible, including those previously shown to affect out-party animus.

Moreover, we take a host of additional steps to ensure robustness. For each of the dependent variables, we run a series of models. We begin by estimating a model that includes an interaction between partisan animus and partisanship while controlling for cases. This interaction directly addresses the first set of hypotheses. In our second hypothesis, we theorize that this relationship should be conditional on the number of cases in a respondent’s county; thus, our second step is to interact all three variables. We then increase the restrictiveness of the model by including progressively more controls. An additional model includes demographic controls, the respondent’s COVID-19-related health risks and a dummy variable if the respondent lives in a state with a Republican governor. Another model brings in political controls, including the strength of the respondent’s partisan social identity68, political interest, issue positions as well as a measure of county partisanship (measured here by the 2016 Trump vote share)—each interacted with the Republican dummy variable. The inclusion of a measure capturing identity strength in particular allows us to ensure that the results we observe are not a proxy for partisan identity. The next and final model adds measures related to the respondent’s news sources and social media use. Figure 3 is based on a model with only the interaction between animus and party with only a few controls (model 1 in Supplementary Tables 9–11), while Figs. 4–7 are based on models with all the control variables and a three-way interaction including logged cases (model 6 in Supplementary Tables 9–11).

We also estimated a model in which we include a triple interaction with in-party affect, cases and partisanship. This tests the possibility that in-party affect—not out-party animus (as we theorize)—is the aspect of affective polarization that is most correlated with responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. We find that the inclusion of in-party affect does not change our out-party animus results, and the in-party affect variable it self does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. These results reinforce not only previous research on affective polarization4, but also the approach in this manuscript. The results are available in model 6 in Supplementary Tables 9–11.

We run different estimation approaches for the behaviour and policy variables. Although the behaviour variable is normally distributed, we estimate models using both ordinary least squares (OLS) and a negative binomial approach since the measure is technically a count of behaviours. The figures in the main text present results from the OLS model, while the negative binomial results are included in Supplementary Table 12. For the policies dependent variable, we present the results of the OLS model. However, the majority of the values of the dependent variable—for both Democrats and Republicans—are clustered at the most supportive values. For this reason, in the Supplementary Information we show that the results are robust to a tobit model (Supplementary Table 13). Our goal with these steps is to show that the results are robust to numerous different model specifications. Happily, our results are consistent across these different models.

In Supplementary Figs. 3–5, we present figures for each of the questions that make up the dependent variable scales individually. Finally, because the key variables in the analyses are not randomly assigned, there always remains the possibility that the findings are the result of unmeasured confounding variables. For this reason, in the Supplementary Results we conducted sensitivity analyses to determine the likelihood of this69. Based on published benchmarks70, it is unlikely that the findings are the result of an unmeasured confounding variable. However, these types of analyses are not commonly used in the analysis of political surveys like this one and the proper benchmarks are not clear in this case. One should be careful, therefore, of concluding too much based on the sensitivity analysis.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available via Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/H7AT3N.

Code availability

All code that supports the findings of this study are available via Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/H7AT3N.

References

Iyengar, S., Sood, G. & Lelkes, Y. Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431 (2012).

Finkel, E. J. et al. Political sectarianism in America: a poisonous cocktail of othering, aversion, and moralization. Science 370, 533–536 (2020).

Partisan Antipathy: More Intense, More Personal (Pew Research Center, 2019); https://pewrsr.ch/3gGRfGp

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N. & Westwood, S. J. The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146 (2019).

Fiorina, M. Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political Stalemate (Hoover Institution Press, 2017).

Rogowski, J. & Sutherland, J. How ideology fuels affective polarization. Polit. Behav. 38, 485–508 (2016).

Levendusky, M. The Partisan Sort (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2009).

Gollwitzer, A. et al. Partisan differences in physical distancing are linked to health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 1186–1197 (2020).

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (eds Austin. W. G. & Worchel, S.) 33–47 (Brooks/Cole, 1979).

Groenendyk, E. Competing motives in a polarized electorate: political responsiveness, identity defensiveness, and the rise of partisan antipathy. Polit. Psychol. 39, 159–171 (2018).

Iyengar, S. & Krupenkin, M. The strengthening of partisan affect. Polit. Psychol. 39, 201–218 (2018).

Huber, G. & Malhotra, N. Political homophily in social relationships: evidence from online dating behavior. J. Polit. 79, 269–283 (2017).

McConnell, C., Margalit, Y., Malhotra, N. & Levendusky, M. The economic consequences of partisanship in a polarized era. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 62, 5–18 (2018).

Shafranek, R. Political considerations in nonpolitical decisions: a conjoint analysis of roommate choice. Polit. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09554-9 (2019).

Lelkes, Y. & Westwood, S. J. The limits of partisan prejudice. J. Polit. 79, 485–501 (2017).

West, E. & Iyengar, S. Partisanship as a social identity: implications for polarization. Polit. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09637-y (2020).

Mason, L. Uncivil Agreement (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2018).

Gentzkow, M., Shapiro, J. & Taddy, M. Measuring group differences in high‐dimensional choices: method and application to congressional speech. Econometrica 87, 1307–1340 (2019).

Lelkes, Y. Policy over party: comparing the effects of candidate ideology and party on affective polarization. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.18 (2019).

Lelkes, Y., Sood, G. & Iyengar, S. The hostile audience: the effect of access to broadband internet on partisan affect. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 61, 5–20 (2017).

Levendusky, M. How Partisan Media Polarize America (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2013).

Lau, R. R., Andersen, D. J., Ditonto, T. M., Kleinberg, M. S. & Redlawsk, D. P. Effect of media environment diversity and advertising tone on information search, selective exposure, and affective polarization. Polit. Behav. 39, 231–255 (2017).

Levy, R. Social media, news consumption, and polarization: evidence from a field experiment. SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3653388 (2020).

Pierce, D. & Lau, R. Polarization and correct voting in U.S. Presidential elections. Elect. Stud. 60, 102048 (2019).

Goren, P., Federico, C. & Kittilson, M. Source cues, partisan identities, and political value expression. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 53, 805–820 (2009).

Bakker, B., Lelkes, Y. & Malka, A. Understanding partisan cue receptivity: tests of predictions from the bounded rationality and expressive utility perspectives. J. Polit. 82, 1061–1077 (2020).

Nicholson, S. Polarizing cues. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 52–66 (2012).

Tajfel, H. & Wilkes, A. Classification and quantitative judgment. Br. J. Psychol. 54, 101–114 (1963).

Armaly, M. & Enders, A. The role of affective orientations in promoting perceived polarization. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2020.24 (2020).

Merkley, E. & Stecula, D. Party cues in the news: Democratic elites, Republican backlash, and the dynamics of climate skepticism. Preprint at https://osf.io/azrxm/ (2020).

Milita, K., Ryan, J. B. & Simas, E. Nothing to hide, nothing to run, or nothing to lose: candidate position-taking in congressional elections. Polit. Behav. 36, 427–449 (2014).

Barber, M. & Pope, J. C. Does party trump ideology? Disentangling party and ideology in America. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 38–54 (2019).

Lelkes, Y. Affective polarization and ideological sorting: a reciprocal, albeit weak, relationship. Forum 16, 67–79 (2018).

Bougher, L. The correlates of discord: identity, issue alignment, and political hostility in polarized America. Polit. Behav. 39, 731–762 (2017).

Webster, S. & Abramowitz, A. The ideological foundations of affective polarization in the U.S. electorate. Am. Polit. Res. 45, 621–647 (2017).

Lipsitz, K. & Pop-Eleches, G. The partisan divide in social distancing. SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3595695 (2020).

Fowler, L., Kettler, J. & Witt, S. Democratic governors are quicker in responding to the coronavirus than Republicans. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/democratic-governors-are-quicker-in-responding-to-the-coronavirus-than-republicans-135599 (6 April 2020).

Hart, P. S., Chinn, S. & Soroka, S. Politicization and polarization in COVID-19 news coverage. Sci. Commun. 42, 679–697 (2020).

McCarty, N. Polarization: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford Univ. Press, 2019).

Gadarian, S., Goodman, S. & Pepinsky, T. Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Preprint at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3562796 (2020).

Allcott, H. et al. Polarization and public health: partisan differences in social distancing during COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 191, 104254 (2020).

Leeper, T. J. & Slothuus, R. Political parties, motivated reasoning, and public opinion formation. Polit. Psychol. 35, 129–156 (2014).

Mullinix, K. Partisanship and preference formation: competing motivations, elite polarization, and issue importance. Polit. Behav. 38, 383–411 (2016).

Groenendyk, E. & Krupnikov, Y. What motivates reasoning? A context-dependent theory of political evaluation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12562 (2020).

Druckman, J. The politics of motivation. Crit. Rev. 24, 199–216 (2012).

Bayes, R., Druckman, J., Goods, A. & Molden, D. When and how different motives can drive motivated political reasoning. Polit. Psychol. 41, 1031–1052 (2020).

Lerman, A. E. & McCabe, K. T. Personal experience and public opinion: a theory and test of conditional policy feedback. J. Polit. 79, 624–641 (2017).

Molden, D. C. & Higgins, E. T. in The Oxford Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning (eds Holyoak, K. J. & Morrison, R. G.) 390–412 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

Brambor, T., Clark, W. & Golder, M. Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 14, 63–82 (2006).

Kam, C. & Franzese, R. Modeling and Interpreting Interactive Hypotheses in Regression Analyses (Univ. of Michigan Press, 2009).

Berry, W., Golder, M. & Milton, D. Improving tests of theories positing interaction. J. Polit. 74, 653–671 (2012).

Leeper, T. J. Interpreting regression results using average marginal effects with R’s margins. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Interpreting-Regression-Results-using-Average-with-Leeper/9615c76bd5d81f7ebbbdac9714619863dc3a2337 (2018).

Rieger, J. M. 40 times Trump said the coronavirus would go away. The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/politics/40-times-trump-said-the-coronavirus-would-go-away/2020/04/30/d2593312-9593-4ec2-aff7-72c1438fca0e_video.html (2 November 2020).

Green, J., Edgerton, J. Naftel, D., Shoub, K. & Cranmer, S. Elusive consensus: polarization in elite communication on the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc2717 (2020).

Gollust, S., Nagler, R. & Fowler, E. The emergence of COVID-19 in the U.S.: a public health and political communication crisis. J. Health Polit. Policy Law https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641506 (2020).

Ahler, D. & Sood, G. The parties in our heads: misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. J. Polit. 80, 964–981 (2018).

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M. & Ryan, J. B. Mis-estimating affective polarization. Working Paper Seires WP-19-25 https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/our-work/working-papers/2019/wp-19-25.html (Northwestern Univ. Inst. for Policy Research, 2020).

Levendusky, M. Americans, not partisans: can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? J. Polit. 80, 59–80 (2018).

Wojcieszak, M. & Warner, B. Can interparty contact reduce affective polarization? A systematic test of different forms of intergroup contact. Polit. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1760406 (2020).

Gerber, A. & Green, D. Misperceptions about perceptual bias. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2, 189–210 (1999).

Fowler, A. Partisan intoxication or policy voting? Q. J. Polit. Sci. 15, 141–179 (2020).

Goren, P. Party identification and core political values. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 882–897 (2005).

Rinehart, R. U.S. face mask usage relatively uncommon in outdoor settings. Gallup (7 August 2020); https://news.gallup.com/poll/316928/face-mask-usage-relatively-uncommon-outdoor-settings.aspx

Baker, P. Trump, in a shift, endorses masks and says virus will get worse. The New York Times (21 July 2020).

Rucker, P. & Kim, S. M. Republican leaders now say everyone should wear a mask—even as Trump refuses and has mocked some who do. The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/republican-leaders-now-say-everyone-should-wear-a-mask--even-as-trump-refuses-and-mocks-those-who-do/2020/06/30/995a32d0-bae9-11ea-80b9-40ece9a701dc_story.html (30 June 2020).

Druckman, J. & Levendusky, M. What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opin. Q. 83, 114–122 (2019).

Beam, M. A., Hutchens, M. J. & Hmielowski, J. D. Facebook news and (de)polarization: reinforcing spirals in the 2016 US election. Inf. Commun. Soc. 21, 940–958 (2018).

Huddy, L., Mason, L. & Aarøe, L. Expressive partisanship: campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 1–17 (2015).

Linden, A., Mathur, M. & VanderWeele, T. Conducting sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding in observational studies using E-values: the evalue package. Stata J. 20, 162–175 (2020).

VanderWeele, T. & Ding, P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 268–274 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Lin and N. Sands for their research assistance, as well as E. Finkel and E. Groenendyk for feedback. Funding for this study was provided by Northwestern University, the University of Arizona and the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennslyvania. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.N.D. fielded the study and provided the deidentified data. J.N.D., S.K., Y.K., M.L. and J.B.R. designed the research, did preliminary analyses and wrote the manuscript. J.B.R. performed the final analyses and constructed the figures and analyses in Supplementary Information.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Human Behaviour thanks Alan Abramowitz, Omer Yair and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Aisha Bradshaw.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Ordered sections as referred to in the text of the paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Druckman, J.N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y. et al. Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat Hum Behav 5, 28–38 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5

This article is cited by

-

How to depolarize your students

Nature Human Behaviour (2024)

-

Evidence from 43 countries that disease leaves cultures unchanged in the short-term

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Cross-partisan discussions reduced political polarization between UK voters, but less so when they disagreed

Communications Psychology (2024)

-

A synthesis of evidence for policy from behavioural science during COVID-19

Nature (2024)

-

Political polarization of news media and influencers on Twitter in the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections

Nature Human Behaviour (2023)