Abstract

For a policy-maker promoting the end of a harmful tradition, conformist social influence is a compelling mechanism. If an intervention convinces enough people to abandon the tradition, this can spill over and induce others to follow. A key objective is thus to activate such spillovers and amplify an intervention’s effects. With female genital cutting as a motivating example, we develop empirically informed analytical and simulation models to examine this idea. Even if conformity pervades decision-making, spillovers can range from irrelevant to indispensable. Our analysis highlights three considerations. First, ordinary forms of individual heterogeneity can severely limit spillovers, and understanding the heterogeneity in a population is essential. Second, although interventions often target samples of the population biased towards ending the harmful tradition, targeting a representative sample is a more robust way to achieve spillovers. Finally, if the harmful tradition contributes to group identity, the success of spillovers can depend critically on disrupting the link between identity and tradition.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

Code is available as Supplementary Software with related details in the Supplementary Information and the Supplementary Software Guide.

References

Nyborg, K. et al. Social norms as solutions. Science 354, 42–43 (2016).

Shell-Duncan, B. & Hernlund, Y. Female ‘circumcision’ in Africa: dimensions of the practice and debates. In Female ‘Circumcision’ in Africa: Culture, Controversy, and Change (eds. Shell-Duncan, B. & Hernlund, Y.) 1–40 (Lynne Rienner, 2000).

Cloward, K. When Norms Collide: Local Responses to Activism Against Female Genital Mutilation and Early Marriage (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Shell-Duncan, B. From health to human rights: female genital cutting and the politics of intervention. Am. Anthropol. 110, 225–236 (2008).

Richerson, P. J. & Boyd, R. Not By Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed the Evolutionary Process. (University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Dolan, P. et al. Influencing behaviour: the mindspace way. J. Economic Psychol. 33, 264–277 (2012).

World Bank Group. Mind, Society, and Behavior: World Development Report 2015. (The World Bank, 2015).

Bicchieri, C. Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Shell-Duncan, B., Wander, K., Hernlund, Y. & Moreau, A. Dynamics of change in the practice of female genital cutting in Senegambia. Soc. Sci. Med. 73, 1275–1283 (2011).

UNFPA-UNICEF. Joint Evaluation of the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/cutting: Accelerating Change. https://www.unfpa.org/admin-resource/unfpa-unicef-joint-evaluation-unfpa-unicef-joint-programme-female-genital (UNFPA, 2013).

Mackie, G., Moneti, F., Shakya, H. & Denny, E. What are social norms? How are they measured. https://www.unicef.org/protection/files/4_09_30_Whole_What_are_Social_Norms.pdf (UNICEF, 2015).

Platteau, J.-P., Camilotti, G. & Auriol, E. Eradicating women-hurting customs. In Towards Gender Equity in Development (eds Anderson, S., Beaman, L. & Platteau, J.) 319–356 (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Malhotra, A., Warner, A., McGonagle, A. & Lee-Rife, S. Solutions to end child marriage: what the evidence shows. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Solutions-to-End-Child-Marriage.pdf (ICRW, 2011).

Lee-Rife, S., Malhotra, A., Warner, A. & Glinski, A. M. What works to prevent child marriage: a review of the evidence. Stud. Fam. Plan. 43, 287–303 (2012).

Bicchieri, C., Jiang, T. & Lindemans, J. W. A social norms perspective on child marriage: the general framework. http://repository.upenn.edu/pennsong/13/ (Penn Social Norms Group, 2014).

Shakya, H. B., Christakis, N. A. & Fowler, J. H. Social network predictors of latrine ownership. Soc. Sci. Med. 125, 129–138 (2015).

World Health Organization. Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44147 (WHO, 2009).

Christakis, N. A. & Fowler, J. H. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. New Engl. J. Med. 358, 2249–2258 (2008).

Mackie, G. Ending footbinding and infibulation: a convention account. Am. Sociol. Rev. 61, 999–1017 (1996).

Prentice, D. A. & Miller, D. T. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 64, 243–256 (1993).

Young, H. P. The evolution of social norms. Annu. Rev. Econ. 7, 359–387 (2015).

Christakis, N. A. & Fowler, J. H. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 370–379 (2007).

Paluck, E. L., Shepherd, H. & Aronow, P. M. Changing climates of conflict: a social network experiment in 56 schools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 566–571 (2016).

Allcott, H. Social norms and energy conservation. J. Public Econ. 95, 1082–1095 (2011).

Hallsworth, M., List, J. A., Metcalfe, R. D. & Vlaev, I. The behavioralist as tax collector: using natural field experiments to enhance tax compliance. J. Public Econ. 148, 14–31 (2017).

Castilla-Rho, J. C., Rojas, R., Andersen, M. S., Holley, C. & Mariethoz, G. Social tipping points in global groundwater management. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 640 (2017).

Koch, C. M. & Nax, H. H. ‘Follow the Data’ – what data says about real-world behavior of commons problems. SSRN https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3075935 (2017).

World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation (WHO, 2018).

Hayford, S. R. Conformity and change: community effects on female genital cutting in Kenya. J. Health Soc. Behav. 46, 121–140 (2005).

Bellemare, M. F., Novak, L. & Steinmetz, T. L. All in the family: explaining the persistence of female genital cutting in West Africa. J. Dev. Econ. 116, 252–265 (2015).

Efferson, C., Vogt, S., Elhadi, A., Ahmed, H. E. F. & Fehr, E. Female genital cutting is not a social coordination norm. Science 349, 1446–1447 (2015).

Howard, J. A. & Gibson, M. A. Frequency-dependent female genital cutting behaviour confers evolutionary fitness benefits. Nat. Ecol. Evolution 1, 0049 (2017).

Vogt, S., Zaid, N. A. M., Ahmed, H. E. F., Fehr, E. & Efferson, C. Changing cultural attitudes towards female genital cutting. Nature 538, 506–509 (2016).

De Cao, E. & Lutz, C. Sensitive survey questions: measuring attitudes regarding female genital cutting through a list experiment. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 80, 871–892 (2018).

Gibson, M. A., Gurmu, E., Cobo, B., Rueda, M. M. & Scott, I. M. Indirect questioning method reveals hidden support for female genital cutting in South Central Ethiopia. PloS One 13, e0193985 (2018).

Efferson, C., Lalive, R., Richerson, P. J., McElreath, R. & Lubell, M. Conformists and mavericks: the empirics of frequency-dependent cultural transmission. Evol. Hum. Behav. 29, 56–65 (2008).

Morgan, T. J. H., Rendell, L. E., Ehn, M., Hoppitt, W. & Laland, K. N. The evolutionary basis of human social learning. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 653–662 (2012).

Muthukrishna, M., Morgan, T. J. & Henrich, J. The when and who of social learning and conformist transmission. Evol. Hum. Behav. 37, 10–20 (2016).

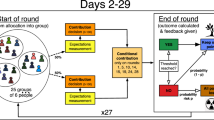

Efferson, C. & Vogt, S. Behavioural homogenization with spillovers in a normative domain. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20180492 (2018).

Shell-Duncan, B. & Hernlund, Y. Are there ‘stages of change’ in the practice of female genital cutting? Qualitative research findings from Senegal and the Gambia. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 10, 57–71 (2006).

Howard, J. A. & Gibson, M. A. Is there a link between paternity concern and female genital cutting in West Africa? Evol. Hum. Behav. 40, 1–11 (2019).

Granovetter, M. Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 1420–1443 (1978).

Watts, D. J. & Dodds, P. Threshold models of social influence. in The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology (eds Bearman, P. & Hedström, P.) 475–497 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Young, H. P. Innovation diffusion in heterogeneous populations: contagion, social influence, and social learning. Am. Economic Rev. 99, 1899–1924 (2009).

Vogt, S., Efferson, C. & Fehr, E. The risk of female genital cutting in Europe: comparing immigrant attitudes toward uncut girls with attitudes in a practicing country. SSM Popul. Health 3, 283–293 (2017).

Schelling, T. C. Hockey helmets, concealed weapons, and daylight saving: a study of binary choices with externalities. J. Confl. Resolut. 17, 381–428 (1973).

Xie, J. et al. Social consensus through the influence of committed minorities. Phys. Rev. E 84, 011130 (2011).

Centola, D., Becker, J., Brackbill, D. & Baronchelli, A. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science 360, 1116–1119 (2018).

Baronchelli, A., Felici, M., Loreto, V., Caglioti, E. & Steels, L. Sharp transition towards shared vocabularies in multi-agent systems. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2006, P06014 (2006).

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L. & Cook, J. M. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 27, 415–444 (2001).

Jackson, M. O. & López-Pintado, D. Diffusion and contagion in networks with heterogeneous agents and homophily. Netw. Sci. 1, 49–67 (2013).

Young, H. P. The dynamics of social innovation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 21285–21291 (2011).

Lu, Q., Korniss, G. & Szymanski, B. K. The naming game in social networks: community formation and consensus engineering. J. Econ. Interact. Coord. 4, 221 (2009).

Thomas, L. ‘Ngaitana (I Will Circumcise Myself)’: lessons from colonial campaigns to ban excision in Meru, Kenya. in Female ‘Circumcision’ in Africa: Culture, Controversy, and Change (eds. Shell-Duncan, B. & Hernlund, Y.) 129–150 (Lynne Rienner, 2000).

Gruenbaum, E. The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

Goodman, R. & Jinks, D. Socializing States: Promoting Human Rights through International Law (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Shell-Duncan, B., Wander, K., Hernlund, Y. & Moreau, A. Legislating change? Responses to criminalizing female genital cutting in Senegal. Law Soc. Rev. 47, 803–835 (2013).

Camilotti, G. Interventions to stop female genital cutting and the evolution of the custom: evidence on age at cutting in Senegal. J. Afr. Econ. 25, 133–158 (2016).

Morgan, T. J. H. & Laland, K. N. The biological bases of conformity. Front. Neurosci. 6, 87 (2012).

Molleman, L. & Gächter, S. Societal background influences social learning in cooperative decision making. Evol. Hum. Behav. 39, 547–555 (2018).

Efferson, C., Lalive, R., Cacault, M. P. & Kistler, D. The evolution of facultative conformity based on similarity. PLoS One 11, e0168551 (2016).

Molleman, L., van den Berg, P. & Weissing, F. J. Consistent individual differences in human social learning strategies. Nat. Commun. 5, 3570 (2014).

Mesoudi, A., Chang, L., Dall, S. R. X. & Thornton, A. The evolution of individual and cultural variation in social learning. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 215–225 (2016).

Boyd, R. & Richerson, P. J. Culture and the Evolutionary Process (University of Chicago Press, 1985).

Krumpal, I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Qual. Quant. 47, 2025–2047 (2013).

Apicella, C. L., Marlowe, F. W., Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. Social networks and cooperation in hunter-gatherers. Nature 481, 497 (2012).

Migliano, A. et al. Characterization of hunter-gatherer networks and implications for cumulative culture. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0043 (2017).

Centola, D. An experimental study of homophily in the adoption of health behavior. Science 334, 1269–1272 (2011).

Acknowledgements

For valuable comments while developing this research, we thank J. Walsh, as well as seminar participants at the universities of Bern, Konstanz, Lausanne, Nottingham and Zurich, the United Nations University in Maastricht, Harvard, and Oxford. C.E. and S.V. also thank the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 100018_185417/1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.E. designed, implemented, and analyzed the models. S.V. surveyed the relevant policy literature. C.E. wrote the paper with input from S.V. and E.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Aisha Bradshaw

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Model details, including Supplementary equations (1)–(25) and Supplementary Figs. 1–54; and Supplementary References.

Supplementary Software Guide

A brief guide explaining Supplementary Software 1–4.

Supplementary Software 1

Custom code for plotting how a policy-maker’s choices affect the distribution of threshold values.

Supplementary Software 2

Custom code for agent-based simulations under heterogeneity in preferences, responses to the intervention, and networks.

Supplementary Software 3

Custom code for numerically simulating a system of difference equations combining ingroup conformity with outgroup anti-conformity.

Supplementary Software 4

Custom code for agent-based simulations combining ingroup conformity with outgroup anti-conformity.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Efferson, C., Vogt, S. & Fehr, E. The promise and the peril of using social influence to reverse harmful traditions. Nat Hum Behav 4, 55–68 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0768-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0768-2

This article is cited by

-

Cooperation without punishment

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

How do you feel about going green? Modelling environmental sentiments in a growing open economy

Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination (2023)

-

Evidence supporting a cultural evolutionary theory of prosocial religions in contemporary workplace safety data

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Global phylogenetic analysis reveals multiple origins and correlates of genital mutilation/cutting

Nature Human Behaviour (2022)

-

Five years of Nature Human Behaviour

Nature Human Behaviour (2022)