Abstract

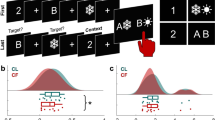

Attending to our inner world is a fundamental cognitive phenomenon1,2,3, yet its neural underpinnings remain largely unknown. Neuroimaging evidence implicates the default network (DN) and frontoparietal control network (FPCN)4; however, the electrophysiological basis for the interaction between these networks is unclear. Here we recorded intracranial electroencephalogram from DN and FPCN electrodes implanted in individuals undergoing presurgical monitoring for refractory epilepsy. Subjects performed an attention task during which they attended to tones (that is, externally directed attention) or ignored the tones and thought about whatever came to mind (that is, internally directed attention). Given the emerging role of theta band connectivity in attentional processes5,6, we examined the theta power correlation between DN and two subsystems of the FPCN as a function of attention states. We found increased connectivity between DN and FPCNA during internally directed attention compared to externally directed attention, which positively correlated with attention ratings. There was no statistically significant difference between attention states in the connectivity between DN and FPCNB. Our results indicate that enhanced theta band connectivity between the DN and FPCNA is a core electrophysiological mechanism that underlies internally directed attention.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The custom MATLAB code used to analyse the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Christoff, K., Irving, Z. C., Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N. & Andrews-Hanna, J. R. Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: a dynamic framework. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 718–731 (2016).

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The restless mind. Psychol. Bull. 132, 946–958 (2006).

Mittner, M., Hawkins, G. E., Boekel, W. & Forstmann, B. U. A neural model of mind wandering. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 570–578 (2016).

Dixon, M. L. et al. Heterogeneity within the frontoparietal control network and its relationship to the default and dorsal attention networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E1598–E1607 (2018).

Baird, B., Smallwood, J., Lutz, A. & Schooler, J. W. The decoupled mind: mind-wandering disrupts cortical phase-locking to perceptual events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26, 2596–2607 (2014).

Helfrich, R. F. et al. Neural mechanisms of sustained attention are rhythmic. Neuron 99, 854–865 (2018).

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330, 932 (2010).

Foster, B. L., Rangarajan, V., Shirer, W. R. & Parvizi, J. Intrinsic and task-dependent coupling of neuronal population activity in human parietal cortex. Neuron 86, 578–590 (2015).

Sormaz, M. et al. Default mode network can support the level of detail in experience during active task states. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9318–9323 (2018).

Zabelina, D. L. & Andrews-Hanna, J. R. Dynamic network interactions supporting internally-oriented cognition. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 40, 86–93 (2016).

Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N., Ellamil, M., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Christoff, K. The wandering brain: meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of mind-wandering and related spontaneous thought processes. Neuroimage 111, 611–621 (2015).

Mason, M. F. et al. Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science 315, 393–395 (2007).

Margulies, D. S. et al. Situating the default-mode network along a principal gradient of macroscale cortical organization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 12574–12579 (2016).

Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Schacter, D. L. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1124, 1–38 (2008).

Raichle, M. E. The brain’s default mode network. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 38, 433–447 (2015).

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R. & Buckner, R. L. Remembering the past to imagine the future: the prospective brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 657–661 (2007).

Kam, J. W. Y., Solbakk, A. K., Endestad, T., Meling, T. R. & Knight, R. T. Lateral prefrontal cortex lesion impairs regulation of internally and externally directed attention. Neuroimage 175, 91–99 (2018).

Spreng, R. N., Stevens, W. D., Chamberlain, J. P., Gilmore, A. W. & Schacter, D. L. Default network activity, coupled with the frontoparietal control network, supports goal-directed cognition. Neuroimage 53, 303–317 (2010).

Dodds, C. M., Morein-Zamir, S. & Robbins, T. W. Dissociating inhibition, attention, and response control in the frontoparietal network using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb. Cortex 21, 1155–1165 (2011).

Yeo, B. T. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011).

Engel, A. K., Gerloff, C., Hilgetag, C. C. & Nolte, G. Intrinsic coupling modes: multiscale interactions in ongoing brain activity. Neuron 80, 867–886 (2013).

Siegel, M., Donner, T. H. & Engel, A. K. Spectral fingerprints of large-scale neuronal interactions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 121–134 (2012).

Foster, B. L., Kaveh, A., Dastjerdi, M., Miller, K. J. & Parvizi, J. Human retrosplenial cortex displays transient theta phase locking with medial temporal cortex prior to activation during autobiographical memory retrieval. J. Neurosci. 33, 10439–10446 (2013).

Hipp, J. F. & Siegel, M. BOLD fMRI correlation reflects frequency-specific neuronal correlation. Curr. Biol. 25, 1368–1374 (2015).

Cooper, P. S. et al. Theta frontoparietal connectivity associated with proactive and reactive cognitive control processes. Neuroimage 108, 354–363 (2015).

Fellrath, J., Mottaz, A., Schnider, A., Guggisberg, A. G. & Ptak, R. Theta-band functional connectivity in the dorsal fronto-parietal network predicts goal-directed attention. Neuropsychologia 92, 20–30 (2016).

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Sepulcre, J., Poulin, R. & Buckner, R. L. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network. Neuron 65, 550–562 (2010).

Mittner, M. et al. When the brain takes a break: a model-based analysis of mind wandering. J. Neurosci. 34, 16286–16295 (2014).

Smallwood, J. et al. Pupillometric evidence for the decoupling of attention from perceptual input during offline thought. PLoS One 6, e18298 (2011).

Colclough, G. L. et al. How reliable are MEG resting-state connectivity metrics? Neuroimage 138, 284–293 (2016).

Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J. & Bates, D. M. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J. Mem. Lang. 59, 390–412 (2008).

Jensen, O. & Mazaheri, A. Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: gating by inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, 186 (2010).

Gao, W. & Lin, W. Frontal parietal control network regulates the anti-correlated default and dorsal attention networks. Hum. Brain Mapp. 33, 192–202 (2012).

Clayton, M. S., Yeung, N. & Cohen Kadosh, R. The roles of cortical oscillations in sustained attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 188–195 (2015).

Sauseng, P., Hoppe, J., Klimesch, W., Gerloff, C. & Hummel, F. C. Dissociation of sustained attention from central executive functions: local activity and interregional connectivity in the theta range. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 587–593 (2007).

Jensen, O. & Tesche, C. D. Frontal theta activity in humans increases with memory load in a working memory task. Eur. J. Neurosci. 15, 1395–1399 (2002).

Tesche, C. D. & Karhu, J. MEG study of hippocampal theta during a working memory task. Biomed. Tech. 44, 74–78 (1999).

Brovelli, A. et al. Beta oscillations in a large-scale sensorimotor cortical network: directional influences revealed by Granger causality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9849–9854 (2004).

Elton, A. & Gao, W. Divergent task-dependent functional connectivity of executive control and salience networks. Cortex 51, 56–66 (2014).

Noonan, K., Jefferies, E., Visser, M. & Ralph, M. A. L. Going beyond inferior prefrontal involvement in semantic control: evidence for the additional contribution of dorsal angular gyrus and posterior middle temporal cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 25, 1824–1850 (2013).

Christoff, K., Keramatian, K., Gordon, A., Smith, R. & Mädler, B. Prefrontal organization of cognitive control according to levels of abstraction. Brain Res. 1286, 94–105 (2009).

Bhatt, M., Lohrenz, T., Camerer, C. & Montague, P. Neural signatures of strategic types in a two-person bargaining game. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19720–19725 (2010).

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T. & Schacter, D. L. Remembering the past and imagining the future: common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia 45, 1363–1377 (2007).

Turnbull, A. et al. The ebb and flow of attention: between-subject variation in intrinsic connectivity and cognition associated with the dynamics of ongoing experience. Neuroimage 185, 286–299 (2019).

Murphy, C. et al. Distant from input: evidence of regions within the default mode network supporting perceptually-decoupled and conceptually-guided cognition. Neuroimage 171, 393–401 (2018).

Vatansever, D., Menon, D. K., Manktelow, A. E., Sahakian, B. J. & Stamatakis, E. A. Default mode dynamics for global functional integration. J. Neurosci. 35, 15254–15262 (2015).

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9673–9678 (2005).

Karapanagiotidis, T., Bernhardt, B. C., Jefferies, E. & Smallwood, J. Tracking thoughts: exploring the neural architecture of mental time travel during mind-wandering. Neuroimage 147, 272–281 (2017).

Dixon, M. L., Fox, K. C. R. & Christoff, K. A framework for understanding the relationship between externally and internally directed cognition. Neuropsychologia 62, 321–330 (2014).

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D. & Schacter, D. L. Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 605–617 (2016).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maj, M., Van der Linden, M. & D’Argembeau, A. Mind-wandering: phenomenology and function as assessed with a novel experience sampling method. Acta Psychol. 136, 370–381 (2011).

Jafarpour, A., Piai, V., Lin, J. J. & Knight, R. T. Human hippocampal pre-activation predicts behavior. Sci. Rep. 7, 5959 (2017).

Flinker, A. et al. Redefining the role of Broca’s area in speech. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 2871–2875 (2015).

Johnson, E. L. et al. Dynamic frontotemporal systems process space and time in working memory. PLoS Biol. 16, e2004274 (2018).

Oostenveld, R., Fries, P., Maris, E. & Schoffelen, J. M. FieldTrip: open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 156869 (2011).

Blenkmann, A. O. et al. iElectrodes: a comprehensive open-source toolbox for depth and subdural grid electrode localization. Front. Neuroinform. 11, 14 (2017).

Destrieux, C., Fischl, B., Dale, A. & Halgren, E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 53, 1–15 (2010).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 134, 9–21 (2004).

Haller, M. et al. Persistent neuronal activity in human prefrontal cortex links perception and action. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 80–91 (2018).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the time put forward by our patients, whose participation was instrumental in this study. We thank A. Jafarpour, A. Breska, J. Zheng, R. Helfrich and V. Piai for discussions, as well as the recording team at each hospital for their help with data collection. This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the James S. McDonnell Foundation (to J.W.Y.K.), Research Council of Norway 240389/F20 and Internal Funding from the University of Oslo (to A.-K.S., T.E. and P.G.L.) and NINDS R3721135 (to R.T.K.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.Y.K. developed the research question and experimental design, analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. R.T.K. contributed to experimental design, data interpretation and revision of the manuscript. J.J.L., A.-K.S., T.E. and P.G.L. contributed to data accessibility and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information: Primary Handling Editor: Marike Schiffer.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kam, J.W.Y., Lin, J.J., Solbakk, AK. et al. Default network and frontoparietal control network theta connectivity supports internal attention. Nat Hum Behav 3, 1263–1270 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0717-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0717-0

This article is cited by

-

A rapid theta network mechanism for flexible information encoding

Nature Communications (2023)

-

The intersection of the retrieval state and internal attention

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Human thirst behavior requires transformation of sensory inputs by intrinsic brain networks

BMC Biology (2022)

-

Functional coupling between frontoparietal control subnetworks bridges the default and dorsal attention networks

Brain Structure and Function (2022)

-

Prediction of stimulus-independent and task-unrelated thought from functional brain networks

Nature Communications (2021)