Abstract

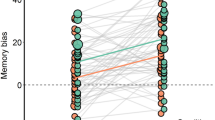

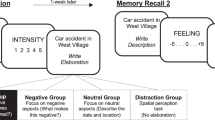

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide1. Early life stress exposure increases risk for depression2 and has been proposed to sensitize the maturing psychophysiological stress system to stress in later life3. In response to stress, positive memory activation has been found to dampen cortisol responses and improve mood in humans4 and to reduce depression-like behaviour in mice5. We used path modelling to examine whether recalling specific positive memories predicts reduced vulnerability to depression (high morning cortisol6,7,8,9 and negative self-cognitions during low mood10,11,12) in adolescents at risk due to early life stress (n = 427, age 14 years)8. We found that positive memory specificity was associated with lower morning cortisol and fewer negative self-cognitions during low mood over the course of one year. Moderated mediation analyses demonstrated that positive memory specificity was related to lower depressive symptoms through fewer negative self-cognitions in response to negative life events reported in the one-year interval. These findings indicate that recalling specific positive life experiences may be a resilience factor13 that helps in lowering depressive vulnerability in adolescents with a history of early life stress.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data supporting the analyses presented in this paper is available at the University of Cambridge research repository (https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.23436) and the corresponding authors’ websites (https://www.annelauravanharmelen.com and www.adriandahlaskelund.com).

Change history

20 May 2019

The original and corrected references are shown in the accompanying Author Correction.

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper

References

Barber, R. M. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 743–800 (2015).

Green, J. G. et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 113–123 (2010).

McLaughlin, K. A., Conron, K. J., Koenen, K. C. & Gilman, S. E. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol. Med. 40, 1647–1658 (2010).

Speer, M. E. & Delgado, M. R. Reminiscing about positive memories buffers acute stress responses. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0093 (2017).

Ramirez, S. et al. Activating positive memory engrams suppresses depression-like behaviour. Nature 522, 335–339 (2015).

Owens, M. et al. Elevated morning cortisol is a stratified population-level biomarker for major depression in boys only with high depressive symptoms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 111, 3638–3643 (2014).

Vreeburg, S. A. et al. Major depressive disorder and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 617–626 (2009).

Goodyer, I. M., Herbert, J., Tamplin, A. & Altham, P. M. E. Recent life events, cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone and the onset of major depression in high-risk adolescents. Br. J. Psychiatry 177, 499–504 (2000).

Mannie, Z. N., Harmer, C. J. & Cowen, P. J. Increased waking salivary cortisol levels in young people at familial risk of depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 617–621 (2007).

Teasdale, J. D. Cognitive vulnerability to persistent depression. Cogn. Emot. 2, 247–274 (1988).

Alloy, L.B., Abramson, L, Stange, J. & Rachel, S. The Oxford Handbook of Mood Disorders (eds. DeRubeis, R. J. & Strunk, D. R.) (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

Teasdale, J. D. & Cox, S. G. Dysphoria: self-devaluative and affective components in recovered depressed patients and never depressed controls. Psychol. Med. 31, 1311–1316 (2001).

Kalisch, R. et al. The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 784–790 (2017).

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330, 932 (2010).

Josephson, B. R., Singer, J. A. & Salovey, P. Mood regulation and memory: repairing sad moods with happy memories. Cogn. Emot. 10, 437–444 (1996).

Tugade, M. M. & Fredrickson, B. L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86, 320–333 (2004).

Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., Bisconti, T. L. & Wallace, K. A. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 730–749 (2006).

Joormann, J., Siemer, M. & Gotlib, I. H. Mood regulation in depression: differential effects of distraction and recall of happy memories on sad mood. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 116, 484–490 (2007).

Park, R. J., Goodyer, I. M. & Teasdale, J. D. Categoric overgeneral autobiographical memory in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 32, 267–276 (2002).

Begovic, E. et al. Positive autobiographical memory deficits in youth with depression histories and their never-depressed siblings. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 329–346 (2017).

Williams, J. M. G. et al. Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychol. Bull. 133, 122–148 (2007).

Young, K. D., Bellgowan, P. S. F., Bodurka, J. & Drevets, W. C. Behavioral and neurophysiological correlates of autobiographical memory deficits in patients with depression and individuals at high risk for depression. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 698–708 (2013).

Sumner, J. A., Griffith, J. W. & Mineka, S. Overgeneral autobiographical memory as a predictor of the course of depression: a meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 48, 614–625 (2010).

Sumner, J. A. et al. Overgeneral autobiographical memory and chronic interpersonal stress as predictors of the course of depression in adolescents. Cogn. Emot. 25, 183–192 (2011).

Alloy, L. B. et al. Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 115, 145–156 (2006).

Schuler, K. L. et al. Diurnal cortisol interacts with stressful events to prospectively predict depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. Health 61, 767–772 (2017).

Beck, A. T. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 969–977 (2008).

Buss, A. H. & Plomin, R. Temperament: Early Developing Personality Traits (Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1984).

Williams, J. M. G. & Broadbent, K. Autobiographical memory in suicide attempters. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 95, 144–149 (1986).

Costello, E. J. & Angold, A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: Checklists, screens, and nets. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 27, 726–737 (1988).

Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36 (2012).

Koenen, K. C. et al. Childhood IQ and adult mental disorders: A test of the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 50–57 (2009).

van Harmelen, A.-L. et al. Adolescent friendships predict later resilient functioning across psychosocial domains in a healthy community cohort. Psychol. Med. 47, 2312–2322 (2017).

Kass, R. E. & Raftery, A. E. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90, 773–795 (1995).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis (Guilford Press, New York, 2013).

Hitchcock, C., Rees, C. & Dalgleish, T. The devil’s in the detail: accessibility of specific personal memories supports rose-tinted self-generalizations in mental health and toxic self-generalizations in clinical depression. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 146, 1286–1295 (2017).

Goodyer, I. M. et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytical psychotherapy versus a brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depressive disorder (IMPACT): a multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 109–119 (2017).

van Harmelen, A.-L. et al. Child abuse and negative explicit and automatic self-associations: the cognitive scars of emotional maltreatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 48, 486–494 (2010).

McCrory, E. J. et al. Autobiographical memory: a candidate latent vulnerability mechanism for psychiatric disorder following childhood maltreatment. Br. J. Psychiatry 211, 216–222 (2017).

Munafò, M. R. & Davey Smith, G. Nature 553, 399–401 (2018).

Gutenbrunner, C., Salmon, K. & Jose, P. E. Do overgeneral autobiographical memories predict increased psychopathological symptoms in community youth? A 3-year longitudinal investigation. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 46, 197–208 (2018).

Browning, M., Holmes, E. A., Charles, M., Cowen, P. J. & Harmer, C. J. Using attentional bias modification as a cognitive vaccine against depression. Biol. Psychiatry 72, 572–579 (2012).

Hallford, D. J., Austin, D. W., Raes, F. & Takano, K. A test of the functional avoidance hypothesis in the development of overgeneral autobiographical memory. Mem. Cogn. 46, 895–908 (2018).

Ali, N., Nitschke, J. P., Cooperman, C. & Pruessner, J. C. Suppressing the endocrine and autonomic stress systems does not impact the emotional stress experience after psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 78, 125–130 (2017).

Hanson, J. L., Hariri, A. R. & Williamson, D. E. Blunted ventral striatum development in adolescence reflects emotional neglect and predicts depressive symptoms. Biol. Psychiatry 78, 598–605 (2015).

Speer, M. E., Bhanji, J. P. & Delgado, M. R. Savoring the past: positive memories evoke value representations in the striatum. Neuron 84, 847–856 (2014).

Pizzagalli, D. A. et al. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated subjects with major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 702–710 (2009).

Haber, S. N. & Knutson, B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 4–26 (2010).

Heller, A. S. et al. Sustained striatal activity predicts eudaimonic well-being and cortisol output. Psychol. Sci. 24, 2191–2200 (2013).

Urry, H. L. Amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. J. Neurosci. 26, 4415–4425 (2006).

Dillon, D. G. & Pizzagalli, D. A. Mechanisms of memory disruption in depression. Trends Neurosci. 41, 137–149 (2018).

Young, K. D. et al. Randomized clinical trial of real-time fMRI amygdala neurofeedbackfor major depressive disorder: effects on symptoms and autobiographical memory recall. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 748–755 (2017).

Russo, S. J., Murrough, J. W., Han, M.-H., Charney, D. S. & Nestler, E. J. Neurobiology of resilience. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1475–1484 (2012).

Hitchcock, C., Werner-Seidler, A., Blackwell, S. E. & Dalgleish, T. Autobiographical episodic memory-based training for the treatment of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 52, 92–107 (2017).

Arditte Hall, K. A., De Raedt, R., Timpano, K. R. & Joormann, J. Positive memory enhancement training for individuals with major depressive disorder. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 47, 155–168 (2018).

Werner-Seidler, A. & Dalgleish, T. The Method of Loci improves longer-term retention of self-affirming memories and facilitates access to mood-repairing memories in recurrent depression. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 4, 1065–1072 (2016).

Dalgleish, T. & Werner-Seidler, A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 596–604 (2014).

Bollen K. A. & Pearl, J. in Handbook of Causal Analysis for Social Research (ed. Morgan, S. L.) 301–328 (Springer, Dordrecht, Germany, 2013).

Biddle, B. J. & Marlin, M. M. Causality, confirmation, credulity, and structural equation modeling. Child Dev. 58, 4–17 (1987).

Abercrombie, H. C. et al. Neural signaling of cortisol, childhood emotional abuse, and depression-related memory bias. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 3, 274–284 (2018).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 593–602 (2005).

Goodyer, I. M., Herbert, J., Secher, S. M. & Pearson, J. Short-term outcome of major depression: I. Comorbidity and severity at presentation as predictors of persistent disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 179–187 (1997).

Gibbs, B. R. & Rude, S. S. Overgeneral autobiographical memory as depression vulnerability. Cognit. Ther. Res. 28, 511–526 (2004).

Goodyer, I. M., Ashby, L., Altham, P. M., Vize, C. & Cooper, P. J. Temperament and major depression in 11 to 16 year olds. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 34, 1409–1423 (1993).

Heron, J. et al. 40,000 memories in young teenagers: psychometric properties of the Autobiographical Memory Test in a UK cohort study. Memory 20, 300–320 (2012).

Sund, A. M., Larsson, B. & Wichstrøm, L. Depressive symptoms among young Norwegian adolescents as measured by the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 10, 222–229 (2001).

Chambers, W. J. et al. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: test-retest reliability of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present Episode Version. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 42, 696–702 (1985).

Wechsler, D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Revised (Psychological Corporation, New York, 1974).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 174, 245–246 (2009).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling 3rd edn (Guilford Press, New York, 2011).

Enders, C. K. & Bandalos, D. L. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct. Equ. Modeling 8, 430–457 (2001).

Nunnally, J. C. Psychometric Theory (McGraw-Hill: New York, 1967).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182 (1986).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Aker Scholarship (A.D.A.), the Royal Society (A.L.v.H.; grant no. DH15017, grant no. RGF/EA/180029, grant no. RGF/R1/180064) and Wellcome Trust (S.S.; grant no. 209127/Z/17/Z). I.M.G. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award and declares consulting to Lundbeck. The funders had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors thank R.A. Kievit for valuable input on the statistical analyses, and K. Ioannidis for important input on a previous version of the manuscript. Finally, the authors thank the participants for their contribution to our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D.A., I.M.G and A.L.v.H conceptualized the study. All authors contributed to the study design. A.D.A. analysed the data and drafted the paper under the supervision of A.L.v.H.; S.S. and I.M.G. provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Results, Supplementary Results, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, and Supplementary Tables 1–7

Supplementary Software

Supplementary R Code

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Askelund, A.D., Schweizer, S., Goodyer, I.M. et al. Positive memory specificity is associated with reduced vulnerability to depression. Nat Hum Behav 3, 265–273 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0504-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0504-3

This article is cited by

-

Bayesian evaluation of diverging theories of episodic and affective memory distortions in dysphoria

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Transdiagnostic distortions in autobiographical memory recollection

Nature Reviews Psychology (2023)

-

A Meta-Analysis of the Influence of Cue Valence on Overgeneral Memory and Autobiographical Memory Specificity Among Youth

Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology (2023)

-

The Interplay Between Adolescent Friendship Quality and Resilient Functioning Following Childhood and Adolescent Adversity

Adversity and Resilience Science (2021)

-

The complex neurobiology of resilient functioning after childhood maltreatment

BMC Medicine (2020)