Abstract

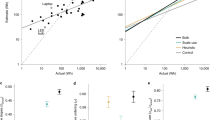

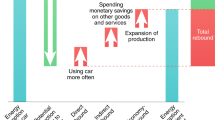

Sustaining large-scale public goods requires individuals to make environmentally friendly decisions today to benefit future generations1,2,3,4,5,6. Recent research suggests that second-order normative beliefs are more powerful predictors of behaviour than first-order personal beliefs7,8. We explored the role that second-order normative beliefs—the belief that community members think that saving energy helps the environment—play in curbing energy use. We first analysed a data set of 211 independent, randomized controlled trials conducted in 27 US states by Opower, a company that uses comparative information about energy consumption to reduce household energy usage (pooled N = 16,198,595). Building off the finding that the energy savings varied between 0.81% and 2.55% across states, we matched this energy use data with a survey that we conducted of over 2,000 individuals in those same states on their first-order personal and second-order normative beliefs. We found that second-order normative beliefs predicted energy savings but first-order personal beliefs did not. A subsequent pre-registered experiment provides causal evidence for the role of second-order normative beliefs in predicting energy conservation above first-order personal beliefs. Our results suggest that second-order normative beliefs play a critical role in promoting energy conservation and have important implications for policymakers concerned with curbing the detrimental consequences of climate change.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data set containing household energy savings from 211 large-scale RCTs is Opower’s propriety data and may not currently be shared publicly. To inquire about access to the proprietary Opower data, please get in touch with J.D.O. (jdpobrien@gmail.com). The survey response data collected on AMT is available on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/jaz4w.

References

Levin, S. A. Public goods in relation to competition, cooperation, and spite. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10838–10845 (2014).

Clark, W. C. & Dickson, N. M. Sustainability science: the emerging research program. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8059–8061 (2003).

Hauser, O. P., Rand, D. G., Peysakhovich, A. & Nowak, M. A. Cooperating with the future. Nature 511, 220–223 (2014).

Fischer, M.-E., Irlenbusch, B. & Sadrieh, A. An intergenerational common pool resource experiment. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 48, 811–836 (2004).

Barrett, S. & Dannenberg, A. Climate negotiations under scientific uncertainty. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17372–17376 (2012).

Dennig, F., Budolfson, M. B., Fleurbaey, M., Siebert, A. & Socolow, R. H. Inequality, climate impacts on the future poor, and carbon prices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15827–15832 (2015).

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A. & Reno, R. R. A focus theory of normative conduct: a theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 24, 201–234 (1991).

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R. & Kallgren, C. A. A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 1015–1026 (1990).

Bem, D. J. Beliefs, Attitudes, and Human Affairs (Brooks/Cole, Oxford, 1970).

Howe, P. D., Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J. R. & Leiserowitz, A. Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 596–603 (2015).

Tertoolen, G., van Kreveld, D. & Verstraten, B. Psychological resistance against attempts to reduce private car use. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 32, 171–181 (1998).

Sedikides, C. & Alicke, M. D. in Oxford Handbook of Motivation (ed. Ryan, R.) Ch. 13 (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2012).

Abrahamse, W., Steg, L., Vlek, C. & Rothengatter, T. Review of intervention studies aimed at household energy conservation. J. Environ. Psychol. 25, 273–291 (2005).

Gillingham, K., Newell, R. & Palmer, K. Energy efficiency policies: a retrospective examination. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 31, 161–192 (2006).

Chiu, C.-Y., Gelfand, M. J., Yamagishi, T., Shteynberg, G. & Wan, C. Intersubjective culture: the role of intersubjective perceptions in cross-cultural research. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 482–493 (2010).

Zou, X. et al. Culture as common sense: perceived consensus versus personal beliefs as mechanisms of cultural influence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 579–597 (2009).

Shteynberg, G., Gelfand, M. J. & Kim, K. Peering into the ‘Magnum Mysterium’ of culture: the explanatory power of descriptive norms. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 40, 46–69 (2009).

Allport, G. The Nature of Prejudice (Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, 1954).

Staub, E. & Pearlman, L. A. in Psychological Interventions in Times of Crisis (eds Barbanel, L. & Sternberg, R. J.) 214–243 (Springer, New York, 2006).

Paluck, E. L. What’s in a norm? Sources and processes of norm change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 594–600 (2009).

Paluck, E. L. Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict using the media: a field experiment in Rwanda. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 574–587 (2009).

Paluck, E. L. & Shepherd, H. The salience of social referents: a field experiment on collective norms and harassment behavior in a school social network. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 103, 899–915 (2012).

Hallsworth, M., List, J. A., Metcalfe, R. D. & Vlaev, I. The behavioralist as tax collector: using natural field experiments to enhance tax compliance. J. Public Econ. 148, 14–31 (2017).

Turner, J., Perkins, H. W. & Bauerle, J. Declining negative consequences related to alcohol misuse among students exposed to a social norms marketing intervention on a college campus. J. Am. Coll. Health 57, 85–94 (2008).

Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N. & Larimer, M. E. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 68, 556–565 (2007).

Allcott, H. Social norms and energy conservation. J. Public Econ. 95, 1082–1095 (2011).

Allcott, H. & Rogers, T. The short-run and long-run effects of behavioral interventions: experimental evidence from energy conservation. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 3003–3037 (2014).

Fischer, C. Feedback on household electricity consumption: a tool for saving energy? Energy Effic. 1, 79–104 (2008).

Costa, D. L. & Kahn, M. E. Energy conservation ‘nudges’ and environmentalist ideology: evidence from a randomized residential electricity field experiment. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 11, 680–702 (2013).

McAuliffe, K., Raihani, N. J. & Dunham, Y. Children are sensitive to norms of giving. Cognition 167, 151–159 (2017).

Fehr, E. & Gächter, S. Fairness and retaliation: the economics of reciprocity. J. Econ. Perspect. 14, 159–182 (2000).

Rand, D. G., Dreber, A., Ellingsen, T., Fudenberg, D. & Nowak, M. A. Positive interactions promote public cooperation. Science 325, 1272–1275 (2009).

Posner, R. & Rasmusen, E. Creating and enforcing norms, with special reference to sanctions. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 19, 369–382 (1999).

Feinberg, M., Willer, R. & Schultz, M. Gossip and ostracism promote cooperation in groups. Psychol. Sci. 25, 656–664 (2014).

Balafoutas, L. & Nikiforakis, N. Norm enforcement in the city: a natural field experiment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 56, 1773–1785 (2012).

Chopik, W. & Motyl, M. Ideological fit enhances interpersonal orientations. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7, 759–768 (2016).

Hauser, O. P., Hendriks, A., Rand, D. G. & Nowak, M. A. Think global, act local: preserving the global commons. Sci. Rep. 6, 36079 (2016).

Allcott, H. Site selection bias in program evaluation. Q. J. Econ. 130, 1117–1165 (2015).

Hauser, O. P., Linos, E. & Rogers, T. Innovation with field experiments: studying organizational behaviors in actual organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 37, 185–198 (2017).

Wooldridge, J. M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach (Upper Level Economics Titles) (Southwestern College Publishing, Nashville, 2012).

O’Brien, R. M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 41, 673–690 (2007).

Côté, S., House, J. & Willer, R. High economic inequality leads higher-income individuals to be less generous. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15838–15843 (2015).

Rand, D. G. & Nowak, M. A. Human cooperation. Trends. Cogn. Sci. 17, 413–425 (2013).

Castro Santa, J., Exadaktylos, F. & Soto-Faraco, S. Beliefs about others’ intentions determine whether cooperation is the faster choice. Sci. Rep. 8, 7509 (2018).

Rand, D. G., Greene, J. D. & Nowak, M. A. Spontaneous giving and calculated greed. Nature 489, 427–430 (2012).

Tinghög, G. et al. Intuition and cooperation reconsidered. Nature 498, E1–E2 (2013).

Bouwmeester, S. et al. Registered Replication Report: Rand, Greene, and Nowak (2012). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 527–542 (2017).

Brozyna, C., Guilfoos, T. & Atlas, S. Slow and deliberate cooperation in the commons. Nat. Sustain. 1, 184–189 (2018).

Hauser, O. P. Running out of time. Nat. Sustain. 1, 162–163 (2018).

Tankard, M. E. & Paluck, E. L. Norm perception as a vehicle for social change. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 10, 181–211 (2016).

Berinsky, A., Huber, G. & Lenz, G. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Polit. Anal. 20, 351–368 (2012).

Huff, C. & Tingley, D. ‘Who are these people?’ Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Res. Polit. 2, 1–12 (2015).

Harrington, J. R. & Gelfand, M. J. Tightness-looseness across the 50 united states. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 11, 7900–7995 (2014).

Jokela, M., Bleidorn, W., Lamb, M. E., Gosling, S. D. & Rentfrow, P. J. Geographically varying associations between personality and life satisfaction in the London metropolitan area. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 725–730 (2015).

Waytz, A., Young, L. L. & Ginges, J. Motive attribution asymmetry for love vs. hate drives intractable conflict. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15687–15692 (2014).

Ross, L. The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: distortions in the attribution process. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 10, 173–220 (1977).

Heilman, M. E. & Haynes, M. C. No credit where credit is due: attributional rationalization of women’s success in male-female teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 905–916 (2005).

Kelley, H. H. & Stahelski, A. J. Social interaction basis of cooperators’ and competitors’ beliefs about others. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 16, 66–91 (1970).

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J. & Ipeirotis, P. G. Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 5, 411–419 (2010).

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T. & Gosling, S. D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 3–5 (2011).

Hauser, D. J. & Schwarz, N. Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than subject pool participants. Behav. Res. Methods 48, 400–407 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to N. Castelo, K. Duke, F. Cushman, H. Foster, J. Greene, G. Kraft-Todd, E. U. Weber and L. Zaval for helpful feedback, and the Center for Decision Sciences at Columbia University, the Behavioral Insights Group at Harvard University and the German Academic Merit Foundation for funding. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D.O. and E.S. oversaw the Opower data collection. J.M.J. and O.P.H. analysed the data, designed the online experiment and wrote the manuscript. J.D.O., E.S. and A.D.G. provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.D.O. and E.S. previously worked at Opower. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supporting Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Results, Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Tables 1–5

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jachimowicz, J.M., Hauser, O.P., O’Brien, J.D. et al. The critical role of second-order normative beliefs in predicting energy conservation. Nat Hum Behav 2, 757–764 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0434-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0434-0

This article is cited by

-

Financial professionals and climate experts have diverging perspectives on climate action

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Delivering affordable clean energy to consumers

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (2024)

-

Trust within human-machine collectives depends on the perceived consensus about cooperative norms

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Neighborhood effects in climate change adaptation behavior: empirical evidence from Germany

Regional Environmental Change (2023)

-

Leveraging social cognition to promote effective climate change mitigation

Nature Climate Change (2022)