Abstract

The rapidly retreating Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers together dominate present-day ice loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and are implicated in runaway deglaciation scenarios. Knowledge of whether these glaciers were substantially smaller in the mid-Holocene and subsequently recovered to their present extents is important for assessing whether current ice recession is irreversible. Here we reconstruct relative sea-level change from radiocarbon-dated raised beaches at sites immediately seawards of these glaciers, allowing us to examine the response of the earth to loading and unloading of ice in the Amundsen Sea region. We find that relative sea level fell steadily over the past 5.5 kyr without rate changes that would characterize large-scale ice re-expansion. Moreover, current bedrock uplift rates are an order of magnitude greater than the rate of long-term relative sea-level fall, suggesting a change in regional crustal unloading and implying that the present deglaciation may be unprecedented in the past ~5.5 kyr. While we cannot preclude minor grounding-line fluctuations, our data are explained most easily by early Holocene deglaciation followed by relatively stable ice positions until recent times and imply that Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers have not been substantially smaller than present during the past 5.5 kyr.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) behaviour under future global warming scenarios remains a great uncertainty in sea-level projections1. Over recent decades, the WAIS has retreated and thinned at accelerating rates in the Amundsen Sea Embayment and is predicted to continue this trend2,3. Of concern is the ongoing mass loss of Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers (Fig. 1), which together drain a large portion of the Amundsen Sea sector and reach deep into the heart of the WAIS. These glaciers are susceptible to rapid retreat because they are being melted from beneath by warm Circumpolar Deep Water4,5. Moreover, Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers rest below sea level on a retrograde slope with no known major topographic highs on which the glaciers could stabilize, and therefore they may be susceptible to runaway retreat via marine ice-sheet instability6,7. Such retreat is likely to trigger extensive ice loss of the WAIS8,9, contributing as much as 3.4 m to global sea level over the next several centuries10.

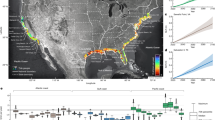

Our study locations are shown in bold text. Textured grey represents the current ice-sheet surface (from Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica35). Shaded grey areas outlined in blue represent ice shelves. Dashed blue lines indicate former ice flow directions through Pine Island Trough (PIT). Bathymetry (blue and white shades) is from GEBCO2019 global dataset36. The basemap was created from the SCAR Antarctic Digital Database.

Geologic evidence has provided insight into ice behaviour in the Amundsen Sea sector. Existing data show that Thwaites11 and Pine Island12 glaciers previously merged in Pine Island Trough to form a palaeo-ice stream, which extended to the continental shelf edge at the Last Glacial Maximum13,14. Marine radiocarbon and terrestrial exposure-age dating show deglaciation of the outer embayment at 12–9 thousand years ago (kyr)15,16, with the grounding line reaching close to its current position by the early Holocene14,15. Cosmogenic exposure-age studies on nunataks near Pope and Pine Island glaciers indicate that ice in this region thinned to current elevations by the mid-Holocene17,18 (Fig. 1).

However, the lack of evidence for ice behaviour since the mid-Holocene allows two plausible hypotheses: (1) Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers reached their current configuration in the mid-Holocene and have remained stable until very recently, or (2) these glaciers continued to retreat to positions behind present-day margins until subsequent re-advance to near current limits in the late Holocene. The former would suggest that the recent rapid ice loss from these glaciers is unprecedented over the past 5 kyr and could evolve into runaway retreat7,8, whereas the latter would imply that current rapid ice recession could be reversible. Discriminating between these scenarios is becoming increasingly urgent as some have proposed irreversible retreat of Thwaites Glacier may be under way19.

Records of relative sea level (RSL) reflect the combined effect of global ocean volume change and local perturbations to the solid Earth and geoid due to glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA). Thus, determining the timing and pattern of Holocene RSL variation can provide information on local ice history since the Last Glacial Maximum as well as on current and past rates of rebound directly related to ice-mass fluctuations (for example, refs. 20,21). Today, rapid uplift is prevalent in the Amundsen Sea Embayment region, where current rates exceed 40 mm yr–1 in some locations22. Holocene RSL data afford information on whether such rates are anomalous and can identify transgressions or periods of slowing RSL fall, both of which can be attributed to ice expansion when changes in global ocean volumes are considered.

Radiocarbon and exposure-age results

Our study focused on three largely granitic island chains (Lindsey, Schaefer and Edwards) in the Amundsen Sea Embayment (Fig. 1). Many islands display striations and glacially polished bedrock at higher elevations16 (>19 m above present-day sea level (asl)). These erosional features probably restrict past sea level to <19 m elevation since deglaciation because such features are destroyed easily by wave erosion. All three island chains have raised beaches (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), the highest of which occur on the Lindsey Islands at ~19 m asl. Thus, available evidence indicates the regional marine limit (the highest elevation reached by the post-glacial sea) is at 19 m elevation. At the Schaefer and Edwards islands, the highest discernible beaches are at ~15 m and 11 m elevation, respectively, although the marine limit may well be a few metres higher on the Schaefer Islands, where it was obscured by snow during our visit.

a–c, Left panel shows Edwards Islands (a), Lindsey Islands (b) and Schaefer Islands (c). Dashed lines in photos on right panels denote raised marine beaches from which shell and bone samples were collected. Photos are from sites corresponding to the red squares in adjacent imagery. Yellow stars in a denote location of additional sampled islands (Photos provided in Supplementary Figs. 2, 3 and 6). Credit: a–c (left), WorldView-2/DigitalGlobe, a Maxar Company; a–c (right), Scott Braddock.

We derived an RSL curve from 55 calibrated radiocarbon ages of shells (limpets, probably Nacella sp.) and penguin bones (probably Adélie) extracted from raised beaches (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 1). We infer that the shells were incorporated into beaches while the molluscs were still alive or shortly thereafter, so radiocarbon dates from shells date beach formation and therefore contemporaneous sea level. However, it is also possible for previously deposited shells to be recycled into younger beaches, so some fraction of shell radiocarbon dates may represent only maximum-limiting ages for beach deposits. In this study, except for three old outliers from the Schaefer Islands, shell radiocarbon ages increase systematically with elevation. Furthermore, ages from similar elevations are tightly clustered, and, as noted in the following, shell ages and a single exposure age at 8 m elevation agree. Thus, we conclude that the shells afford actual—rather than apparent—ages for the beaches and that the true RSL curve must pass through the shell data (Fig. 3a; see Supplementary Information). Extrapolating the trend in shell ages to the marine limit at 19 m indicates that the marine limit dates to 5.5 kyr. In contrast to the shells, we infer that bone samples, mostly surface finds from relict penguin nests, were deposited only after a beach uplifted above sea level. They afford minimum-limiting ages for the beaches, and therefore the RSL curve must lie on or below the elevation of these samples.

a, RSL curve based on radiocarbon ages of shells from raised beaches. All samples are presented as calibrated radiocarbon ages for shells and bones with horizontal bars indicating 2-sigma errors. The solid black line with associated bootstrap confidence intervals is an interpolation of the shell data (see Supplementary Information) using the method of ref. 37. The horizontal dashed black line represents the proposed regional marine limit (elevation of highest sampled beach) at 19 m. Elevation errors (Methods) associated with radiocarbon samples are represented by vertical bars on each data point and range from 0.3 to 0.7 m. Vertical error bars for Lindsey Island samples (0.3 m) are smaller than symbols at this scale. b, Comparison of RSL data with GIA model predictions derived using two different ice-history models (ICE-6G_C27,32 and W1228,33). For each ice-history model, two curves are shown; these represent RSL change assuming either a strong (solid lines, upper mantle viscosity = 5 × 1020 Pa s) or a weak (dashed lines, upper mantle viscosity = 5 × 1019 Pa s) Earth model. The lithosphere thickness is set at 71 km (ref. 34).

In addition to shells and bones, we also measured cosmogenic 10Be from four bedrock samples to provide additional information on the timing of deglaciation. Two samples from the Lindsey Islands (LD-19-C1 and LD-19-C2), both from striated bedrock above the inferred marine limit, yielded ages of 7.9 ± 0.3 kyr and 8.8 ± 0.2 kyr (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that the islands became ice free at approximately this time. These ages are younger than two published 10Be bedrock exposure ages from the Lindsey Islands (recalculated 10.5 ± 0.4 kyr, 15.4 ± 0.7 kyr (ref. 16); Supplementary Table 3). The latter of these published ages was excluded by ref. 16 as having previous exposure. The former also could have previous exposure, but alternatively could reflect slightly earlier deglaciation of the other side of the island from our samples. Our ages are the same as that of a similar-elevation sample from the Jaynes Islands (9.0 ± 0.5 kyr; ISL-3 in16), 50 km from the Lindsey Islands.

In contrast to data from the Lindsey Islands, our two exposure ages from the Edwards Islands of bedrock at 19.1 m elevation yielded an average age of 3.9 ± 0.1 kyr (Fig. 3a). These much-younger ages may reflect either delayed deglaciation of the Edwards Islands relative to the Lindsey and Schaefer islands or emergence of the bedrock from the ocean. If the latter, the 10Be ages appear too young when compared with the radiocarbon-derived RSL curve. Moreover, it would require the local marine limit on the Edwards Islands to be at or above 19 m elevation, something for which we did not find evidence. Because of these factors, and the fact that the age of the samples is approximately equal to the age of the observed local marine limit at 11 m elevation (on the basis of the RSL curve), we favour the interpretation of delayed deglaciation, of either local glacier ice or a remnant stagnant ice block, for these ages.

A recalculated age of 2.8 ± 0.2 kyr (Fig. 3a) from an erratic boulder at 8 m elevation on an island 5 km north of the Edwards Islands was previously interpreted as representing retreat of the Canisteo Peninsula ice front23. However, this exposure age is indistinguishable from radiocarbon-dated shells in beach deposits at the same elevation, so must record emergence rather than deglaciation.

Broader implications of RSL data

Regardless of the interpretation of the exposure-age data, the radiocarbon-constrained RSL curve (Fig. 3a) implies uninterrupted RSL fall in the Amundsen Sea Embayment since 5.5 kyr. We attribute this to unloading of the ice mass dominated by Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers. Although the shell data form an approximately linear array, an exponential curve also could fit the data with reasonable confidence. The data indicate monotonic RSL fall, which is consistent with a simple unloading history (for example, ref. 24). More complex curves, including those showing evidence of marine transgression, typically reflect complicated glacial histories including re-advance (for example, refs. 20,21,25). Our RSL curve does not provide evidence for Holocene ice thickness fluctuations large enough to slow or reverse isostatic rebound following early Holocene mass loss. Although we cannot exclude the possibility of minor grounding-line oscillations, these RSL data do not indicate substantial mass fluctuations in the Amundsen Sea Embayment since 5.5 kyr.

Our results show that the Amundsen Sea region experienced on average ~3.5 mm yr–1 of RSL fall between 5.5 and 0.3 kyr (Fig. 3a). By contrast, bedrock uplift rates are currently 15 mm yr–1 at sites 60–95 km from our field sites and as much as 41 mm yr–1 elsewhere in the Amundsen Sea Embayment22. Although RSL change reflects multiple factors in addition to bedrock uplift (for example, ocean volume change), the large difference we observe between modern bedrock uplift rates and Holocene RSL change requires that a recent increase in the rate of viscoelastic uplift is contributing to current high rates of isostatic adjustment. These rates are linked to contemporary ice-mass loss in this region22, which appears to be unprecedented over the past 5.5 kyr.

The exposure ages from the Lindsey Islands, along with the radiocarbon date of 10.7 kyr from a reworked shell from the Schaefer Islands, indicate that the eastern Amundsen Sea Embayment continental shelf was deglaciated at 11–9 kyr. These ages are consistent with marine geological records that show retreat of the grounding line to its modern position by the early Holocene15. However, beaches apparently did not develop until ~5.5 kyr. Given the proximity of the islands to the current ice margin on the Canisteo Peninsula (<2 km), a possible explanation for the delay is the presence of an ice shelf until ~5.5 kyr, as suggested by ref. 17. An ice shelf that surrounded (but did not cover) the islands would prevent beaches from forming but allow marine organisms to live offshore and 10Be to accumulate in exposed bedrock. This hypothesis is consistent with evidence from marine sediment cores that indicates a remnant ice shelf persisted in the Amundsen Sea Embayment until at least 7.5 kyr (ref. 26). Perennial land-fast sea ice could have the same effect of preventing beach formation.

Comparison with GIA models

The GIA models for Antarctica typically predict RSL rise in the early Holocene, a marine limit at ~20 m asl and RSL fall in the mid to late Holocene27,28. These GIA model results agree relatively well with observations where extensive RSL data exist (for example, the Ross Sea24,29 and Marguerite Bay30,31). Existing RSL data commonly show raised beach deposits recording exponential RSL fall in the mid to late Holocene. Our RSL data from Pine Island Bay display similar features. We compared our RSL data with GIA model predictions generated using two different Antarctic ice-history models, ICE-6G_C27,32 and W1228,33 (Fig. 3b). In W12, the islands in this study become ice free between 11 and 10.5 kyr, and in ICE6G_C, between 8.5 and 8.0 kyr. Predictions were generated separately for all three island groups, but since all sites lie within 30 km, model predictions differ by only ~2 m at all sites for the late Holocene. For this reason, Fig. 3b shows the averaged-RSL prediction for all three island groups. Results are shown in Fig. 3b for a strong (upper mantle viscosity = 5 × 1020 Pa s) and a weak (upper mantle viscosity = 5 × 1019 Pa s) Earth rheology model. The Amundsen Sea Embayment is known to have a relatively thin lithosphere34 with a very low upper mantle viscosity22. The ICE-6C_C model, combined with the weaker Earth rheology model, provides the best fit to our RSL data. In addition, the exponential curve produced by the weaker Earth rheology model fits within the confidence bounds of our RSL reconstruction, whereas that of the strong Earth rheology model does not and overestimates regional Holocene RSL. However, none of the models is consistent with the exposure ages on bedrock above the marine limit or with our interpretation of the elevation of the marine limit based on the upper limit of marine sediments and the lower limit of glacial polish and striations. All of the GIA models in Fig. 3b predict that the exposure-age samples at 19–26 m elevation should have been under water at the time of deglaciation and consequently not exposed to cosmic radiation. Therefore, although the ICE-6G_C (weak) model fits our RSL data between 0 and 4 kyr (Fig. 3b), we infer that none of the models considered here accurately captures the mid- to late Holocene RSL history of the region.

In summary, the Holocene RSL record presented here puts into context the current rapid bedrock uplift near the grounding lines of Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers and shows a monotonic fall in RSL since the mid-Holocene. Although the resolution of the RSL curve does not preclude the possibility of minor marginal fluctuations of Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers during the past ~5.5 kyr, this record is best explained by the hypothesis that ice reached close to its current margin in the mid-Holocene and has remained in the vicinity of that position since, without large-scale glacier recession or re-advance. Thus, there remains no direct evidence that Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers were substantially smaller than present during the present interglacial period, and the present-day rate of ice recession appears to be unprecedented in the past ~5.5 yr.

Methods

Field sampling

Field operations were part of cruise NBP1902 conducted from the US research vessel the Nathaniel B. Palmer. Marine organic material (shells, probably from the limpet Nacella, and bones, probably from Adélie penguins (Supplementary Fig. 7)) were collected from raised marine beaches. Samples were found beneath boulders (up to 25 cm diameter) or in ~0.5 m deep excavations. We collected a minimum of three samples from each beach where possible. We avoided surface samples because they are more likely to be modern in an area heavily colonized by penguins at the present day. Samples for exposure-age dating were collected from bedrock outcrops using a hammer and chisel. There was no topographic shielding.

We determined the elevation relative to sea level (here defined as the EGM96 geoid) of at least one location on each distinct raised beach using a Septentrio APS3 high-precision Global Positioning System (GPS) unit with differential correction relative to a temporary base station deployed during each sampling period and located additional sample locations using uncorrected handheld GPS. To determine the elevations of sample locations lacking DGPS positions, but that are still located on corresponding beach ridges, we used photogrammetric digital elevation models (DEMs) of each island group prepared by the Polar Geospatial Center from DigitalGlobe satellite imagery. We registered each DEM to the Differential GPS (DGPS) data by applying a vertical offset determined to minimize mean square differences between DEM and DGPS elevations for DGPS survey points, and then sampled elevations from the corrected DEMs for all sample locations. The elevation uncertainty is estimated from the distribution of the residuals between the DGPS points and the elevations of the corrected DEMs at those locations and ranges from 0.3 to 0.7 m. We applied the DEM-derived elevation uncertainties to all samples in Fig. 3 to account for undulations in beach ridges.

Radiocarbon dates

Radiocarbon samples were prepared at the University of Maine Glacial Geology and Geochronology Laboratory. We cleaned shell samples in ultrapure water overnight in an ultrasonic bath before drying, weighing and shipping them to the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (NOSAMS) facility for dating. For bone samples, we extracted collagen following procedures modified from the University of California Santa Cruz Stable Isotope Laboratory (https://websites.pmc.ucsc.edu/~silab/ea.collagen_SOP.php). Pieces (50–100 mg) of bone were washed in ultrapure water for 24 hours in a sonicator and dried overnight. Then samples were decalcified in a 0.5 N HCL solution for 24–48 hours. Next, we rinsed the samples and let them sit in ~10 ml of 0.1 N NaOH solution overnight to remove contaminants. To defat samples, they were subjected to multiple baths in petroleum ether while in an ultrasonic bath. Last, we rinsed and dried the collagen samples before sending them to the Environmental Geochemistry Laboratory at Bates College for carbon/nitrogen ratio (C/N) analysis. Samples with a C/N ratio between 2.9 and 3.6 were considered to have sufficiently well-purified collagen to be suitable for radiocarbon dating38. We sent collagen samples within the appropriate C/N range to the NOSAMS facility for radiocarbon dating. Resultant radiocarbon ages were converted to calendar yr bp using CALIB version 8.139 and the Marine20 calibration dataset40. Although this calibration dataset is not optimized for polar regions40, it is the best correction available at present (P. Reimer, personal communication). We applied a delta-R value of 610 ± 110 yr, recalculated from the Holocene Antarctic coral dataset41 for specific use with Marine2020.

Cosmogenic exposure-age dating

Four bedrock samples were processed at the University of Maine Cosmogenic Isotope Laboratory. We crushed and sieved samples and subjected them to froth flotation, followed by a sequence of HF/HNO3 leaches to isolate pure quartz (as determined by ICP-OES). We weighed approximately 30 g of pure quartz for each sample and spiked them with an in-house 10Be carrier made from phenakite. Following standard ion-exchange chemistry42, samples were precipitated as hydroxides, converted to BeO and then packed in cathodes with niobium. The 10Be/9Be ratios were measured at the Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Samples ran with high 9Be currents (20–30 microamps). The full 10Be/9Be procedural blank for the batch was 3.6E−16. We calculated ages with version 3 of the online exposure-age calculator described by ref. 43 and subsequently updated using the default calibration dataset44 and ‘St’ scaling45,46. Ages in the text are given with 1-sigma internal errors, whereas those plotted on the RSL curve are shown with 1-sigma external errors that incorporate uncertainties in production rate and scaling for more realistic comparison to radiocarbon ages.

Data availability

The authors state that all data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and in the Supplementary Information. They also can be found in public databases, including the United States Antarctic Program Data Center (https://doi.org/10.15784/601554) and the ICE-D cosmogenic database (https://version2.ice-d.org/antarctica/site/EDWARDSIS/ and https://version2.ice-d.org/antarctica/site/LINDSI/).

References

Bamber, J. L., Oppenheimer, M., Kopp, R. E., Aspinall, W. P. & Cooke, R. M. Ice sheet contributions to future sea-level rise from structured expert judgment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1195–1120 (2019).

Rignot, E. et al. Four decades of Antarctic Ice Sheet mass balance from 1979–2017. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1095–1103 (2019).

Milillo, P. et al. Heterogeneous retreat and ice melt of Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3433 (2019).

Pritchard, H. et al. Antarctic ice-sheet loss driven by basal melting of ice shelves. Nature 484, 502–505 (2012).

Holland, D., Nicholls, K. & Basinski, A. The Southern Ocean and its interaction with the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Science 367, 1326–1330 (2020).

Joughin, I. & Alley, B. R. Stability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in a warming world. Nat. Geosci. 4, 506–513 (2011).

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J., Morlighem, M., Seroussi, H. & Scheuchl, B. Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith, and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3502–3509 (2014).

Hughes, T. The weak underbelly of the West Antarctic Ice-Sheet. J. Glaciol. 27, 518–525 (1981).

DeConto, R. M. & Pollard, D. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature 531, 591–597 (2016).

Fretwell, H. D. et al. Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica. Cryosphere 7, 375–393 (2013).

Hogan, K. A. et al. Revealing the former bed of Thwaites Glacier using sea-floor bathymetry. Cryosphere 14, 2883–2908 (2020).

Nitsche, F. et al. Paleo ice flow and subglacial meltwater dynamics in Pine Island Bay, West Antarctica. Cryosphere 7, 249–262 (2013).

Graham, A. G. C. et al. Flow and retreat of the late Quaternary Pine Island–Thwaites palaeo-ice stream, West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. 115, F03025 (2010).

Larter, R. D. et al. Reconstruction of changes in the Amundsen Sea and Bellingshausen Sea sector of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet since the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 100, 55–86 (2014).

Hillenbrand, C.-D. et al. Grounding-line retreat of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet from inner Pine Island Bay. Geology 41, 35–38 (2013).

Lindow, J. et al. Glacial retreat in the Amundsen Sea sector, West Antarctica—first cosmogenic evidence from central Pine Island Bay and the Kohler Range. Quat. Sci. Rev. 98, 166–173 (2014).

Johnson, J. S. et al. Rapid thinning of Pine Island Glacier in the early Holocene. Science 343, 999–1001 (2014).

Johnson, J. S. et al. Deglaciation of Pope Glacier implies widespread early Holocene ice sheet thinning in the Amundsen Sea sector of Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 548, 116501 (2020).

Joughin, I., Smith, B. & Medley, B. Marine ice sheet collapse potentially under way for the Thwaites Glacier basin, West Antarctica. Science 344, 735–738 (2014).

Motyka, R. Little Ice Age subsidence and post Little Ice Age uplift at Juneau, Alaska, inferred from dendrochronology and geomorphology. Quat. Res. 59, 300–309 (2003).

Hall, B. L. Holocene relative sea-level changes and ice fluctuations in the South Shetland Islands. Glob. Planet. Change 74, 15–26 (2010).

Barletta, V. et al. Observed rapid bedrock uplift in Amundsen Sea Embayment promotes ice-sheet stability. Science 360, 1335–1339 (2018).

Johnson, J. S., Bentley, M. J. & Gohl, K. First exposure ages from the Amundsen Sea Embayment, West Antarctica: the late Quaternary context for recent thinning of Pine Island, Smith, and Pope glaciers. Geology 36, 223–226 (2008).

Hall, B., Baroni, C. & Denton, G. Holocene relative sea-level history of the Southern Victoria Land Coast, Antarctica. Glob. Planet. Change 42, 241–263 (2004).

Simms, A. R., Ivins, E. R., DeWitt, R., Kouremenos, P. & Simkins, L. M. Timing of the most recent Neoglacial advance and retreat in the south Shetland Islands, Antarctic Peninsula: insights from raised beaches and Holocene uplift rates. Quat. Sci. Rev. 47, 41–55 (2012).

Hillenbrand, C.-D. et al. West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat driven by Holocene warm water incursions. Nature 547, 43–48 (2017).

Argus, D. F., Peltier, W. R., Drummond, R. & Moore, A. W. The Antarctic component of post glacial rebound Model ICE-6G_C (VM5a) based upon GPS positioning, exposure age dating of ice thicknesses and sea level histories. Geophys. J. Int. 198, 537–563 (2014).

Whitehouse, P. L., Bentley, K. J., Milne, G. A., King, M. & Thomas, I. D. A new glacial isostatic adjustment model for Antarctica: calibrated and tested using observations of relative sea level change and present day uplift rates. Geophys. J. Int. 190, 1464–1482 (2012).

Baroni, C. & Hall, L. H. A new Holocene relative sea-level curve for Terra Nova Bay, Victoria Land, Antarctica. J. Quat. Sci. 19, 377–396 (2004).

Bentley, M., Hodgson, D., Smith, J. & Cox, N. Relative sea level curves for the South Shetland Islands and Marguerite Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1203–1216 (2005).

Simkins, L. M., Simms, A. R. & DeWitt, R. Relative sea-level history of Marguerite Bay, Antarctic Peninsula derived from optically stimulated luminescence-dated beach cobbles. Quat. Sci. Rev. 77, 141–155 (2013).

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. F. & Drummond, R. Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: the global ICE-6G_C (VM5a) model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 450–487 (2015).

Whitehouse, P. L., Bentley, M. J. & Le Brocq, A. M. A deglacial model for Antarctica: geological constraints and glaciological modeling as a basis for a new model of Antarctica glacial isostatic adjustment. Quat. Sci. Rev. 32, 1–24 (2012).

Heeszel, D. S. et al. Upper mantle structure of central and West Antarctica from array analysis of Rayleigh wave phase velocities. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 121, 1758–1775 (2016).

Howat, I. M., Porter, C., Smith, B. E., Noh, M.-J. & Morin, P. The Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica. Cryosphere 13, 665–674 (2019).

Weatherall P. et al. The GEBCO_2019 Grid—A Continuous Terrain Model of the Global Oceans and Land (British Oceanographic Data Centre, National Oceanography Centre and NERC, 2019); https://doi.org/10.5285/836f016a-33be-6ddc-e053-6c86abc0788e

Lougheed, B. C. & Obrochta, S. P. A rapid, deterministic age–depth modeling routine for geological sequences with inherent depth uncertainty. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 122–133 (2019).

Ambrose, S. H. Preparation and characterization of bone and tooth collagen for isotopic analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 17, 431–451 (1990).

Stuiver, M., Reimer, P. J. & Reimer, R. W. CALIB Version 8.2 (accessed 30 March 2021); http://calib.org

Heaton, T. et al. Marine20—the marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 cal bp). Radiocarbon 62, 779–820 (2020).

Hall, B. L., Henderson, G. M., Baroni, C. & Kellogg, T. B. Constant Holocene Southern-Ocean 14C reservoir ages and ice-shelf flow rates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 296, 115–123 (2010).

Hall, B. L., Lowell, T. V. & Brickle, P. Multiple glacial maxima of similar extent at ∼20–45 ka on Mt Usborne, East Falkland, South Atlantic region. Quat. Sci. Rev. 250, 106677 (2020).

Balco, G., Stone, J., Lifton, N. & Dunai, T. A complete and easily accessible means of calculating surface exposure ages or erosion rates from 10Be and 26Al measurements. Quat. Geochronol. 3, 174–195 (2008).

Borchers, B. et al. Geological calibration of spallation production rates in the CRONUS-Earth project. Quat. Geochronol. 31, 188–198 (2016).

Lal, D. Cosmic ray labeling of erosion surfaces: in situ nuclide production rates and erosion models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 104, 424–439 (1991).

Stone, J. O. Air pressure and cosmogenic isotope production. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 753–23,759 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the ‘Geological History Constraints’ project, a component of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration. We thank C. Beeler, N. Fenney, V. Fitzgerald, A. Fox, K. Hogan, B. Johnson, J. Kirkham, E. Rush, UNAVCO, the Polar Geospatial Center and the Captain and Crew of the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer for assistance. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant OPP-1738989—S.B., B.L.H., G.B., M.S., B.M.G. and SC) and the Natural Environment Research Council (grants NE/S006710/1 and NE/S006753/1—J.S.J., D.H.R. and J.W.). This is ITGC Contribution No. ITGC-050.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B., S.C., B.M.G., B.L.H., J.S.J., D.H.R. and J.W. conceived the overarching ‘Geological History Constraints’ project of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration. B.L.H. developed and directed the RSL component. S.B. and M.S. carried out the fieldwork and collected the samples. S.B. and B.L.H. performed laboratory work. P.L.W. provided GIA model output. G.B. constructed the age model for the RSL curve. S.B. and B.L.H. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Lauren Simkins, Carlo Baroni and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: James Super, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion, Figs. 1–8 and Tables 1–3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Braddock, S., Hall, B.L., Johnson, J.S. et al. Relative sea-level data preclude major late Holocene ice-mass change in Pine Island Bay. Nat. Geosci. 15, 568–572 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00961-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00961-y

This article is cited by

-

Assessing demographic and economic vulnerabilities to sea level rise in Bangladesh via a nighttime light-based cellular automata model

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheet during the pre-industrial Holocene

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2022)