Abstract

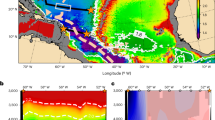

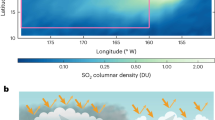

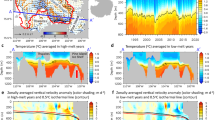

Ocean CO2 uptake accounts for 20–40% of the post-industrial sink for anthropogenic CO2. The uptake rate is the product of the CO2 interfacial concentration gradient and its transfer velocity, which is controlled by spatial and temporal variability in near-surface turbulence. This variability complicates CO2 flux estimates and in large part reflects variable sea surface microlayer enrichments in biologically derived surfactants that cause turbulence suppression. Here we present a direct estimate of this surfactant effect on CO2 exchange at the ocean basin scale, with derived relationships between its transfer velocity determined experimentally and total surfactant activity for Atlantic Ocean surface seawaters. We found up to 32% reduction in CO2 exchange relative to surfactant-free water. Applying a relationship between sea surface temperature and total surfactant activity to our results gives monthly estimates of spatially resolved ‘surfactant suppression’ of CO2 exchange. Large areas of reduced CO2 uptake resulted, notably around 20° N, and the magnitude of the Atlantic Ocean CO2 sink for 2014 was decreased by 9%. This direct quantification of the surfactant effect on CO2 uptake at the ocean basin scale offers a framework for further refining estimates of air–sea gas exchange up to the global scale.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

06 June 2018

In the version of this Article originally published, in the ‘Acknowledgements’ section the authors neglected to include the following text: “The Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT) is an international effort, endorsed by the International Ocean Carbon Coordination Project (IOCCP), the Surface Ocean Lower Atmosphere Study (SOLAS) and the Integrated Marine Biosphere Research (IMBeR) programme, to deliver a uniformly quality-controlled surface ocean CO2 database. The many researchers and funding agencies responsible for the collection of data and quality control are thanked for their contributions to SOCAT.” This has now been added in the online versions of the Article.

References

Upstill-Goddard, R. C. Air–sea gas exchange in the coastal zone. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 70, 388–404 (2006).

Asher, W. E. The effects of experimental uncertainty in parameterizing air–sea gas exchange using tracer experiment data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 131–139 (2009).

Ho, D. T. et al. Toward a universal relationship between wind speed and gas exchange: gas transfer velocities measured with 3He/SF6 during the Southern Ocean Gas Exchange Experiment. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C00F04 (2011).

Nightingale, P. D. et al. In situ evaluation of air–sea gas exchange parameterizations using novel conservative and volatile tracers. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 373–387 (2000).

Wanninkhof, R. Relationship between wind-speed and gas-exchange over the ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 7373–7382 (1992).

Wanninkhof, R. & McGillis, W. R. A cubic relationship between air–sea CO2 exchange and wind speed. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 1889–1892 (1999).

Bock, E. J., Hara, T., Frew, N. M. & McGillis, W. R. Relationship between air–sea gas transfer and short wind waves. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 104, 25821–25831 (1999).

Frew, N. M., Goldman, J. C., Dennett, M. R. & Johnson, A. S. Impact of phytoplankton-generated surfactants on air–sea gas-exchange. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 95, 3337–3352 (1990).

Sabbaghzadeh, B., Upstill-Goddard, R. C., Beale, R., Pereira, R. & Nightingale, P. D. The Atlantic Ocean surface microlayer from 50°N to 50°S is ubiquitously enriched in surfactants at wind speeds up to 13 m s−1. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2852–2858 (2017).

Wurl, O., Miller, L. & Vagle, S. Production and fate of transparent exopolymer particles in the ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 116, C00H13 (2011).

Brockmann, U. H., Huhnerfuss, H., Kattner, G., Broecker, H. C. & Hentzschel, G. Artificial surface-films in the sea area near Sylt. Limnol. Oceanogr. 27, 1050–1058 (1982).

Leck, C. & Bigg, E. K. Aerosol production over remote marine areas—a new route. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3577–3580 (1999).

Cunliffe, M. et al. Sea surface microlayers: a unified physicochemical and biological perspective of the air–ocean interface. Progress. Oceanogr. 109, 104–116 (2013).

Zancker, B., Bracher, A., Rottgers, R. & Engel, A. Variations of the organic matter composition in the sea surface microlayer: a comparison between open ocean, coastal, and upwelling sites off the Peruvian coast. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2369 (2017).

Goldman, J. C., Dennett, M. R. & Frew, N. M. Surfactant effects on air sea gas-exchange under turbulent conditions. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 35, 1953–1970 (1988).

McKenna, S. P. & McGillis, W. R. The role of free-surface turbulence and surfactants in air-water gas transfer. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 47, 539–553 (2004).

Tsai, W. T. & Liu, K. K. An assessment of the effect of sea surface surfactant on global atmosphere–ocean CO2 flux. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 108, 3127 (2003).

Salter, M. E. et al. Impact of an artificial surfactant release on air–sea gas fluxes during Deep Ocean Gas Exchange Experiment II. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 116, C11016 (2011).

Wurl, O. & Holmes, M. The gelatinous nature of the sea-surface microlayer. Mar. Chem. 110, 89–97 (2008).

Sieburth, J. M. et al. Dissolved organic matter and heterotrophic microneuston in the surface microlayers of the North Atlantic. Science 194, 1415–1418 (1976).

Lass, K. & Friedrichs, G. Revealing structural properties of the marine nanolayer from vibrational sum frequency generation spectra. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 116, C08042 (2011).

Kuznetsova, M., Lee, C., Aller, J. & Frew, N. Enrichment of amino acids in the sea surface microlayer at coastal and open ocean sites in the North Atlantic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 1605–1619 (2004).

Tilstone, G. H., Airs, R. L., Martinez-Vicente, V., Widdicombe, C. & Llewellyn, C. High concentrations of mycosporine-like amino acids and colored dissolved organic matter in the sea surface microlayer off the Iberian Peninsula. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1835–1850 (2010).

Schmidt, R. & Schneider, B. The effect of surface films on the air–sea gas exchange in the Baltic Sea. Mar. Chem. 126, 56–62 (2011).

Pereira, R., Schneider-Zapp, K. & Upstill-Goddard, R. C. Surfactant control of gas transfer velocity along an offshore coastal transect: results from a laboratory gas exchange tank. Biogeosciences 13, 3981–3989 (2016).

Schneider-Zapp, K., Salter, M. E. & Upstill-Goddard, R. C. An automated gas exchange tank for determining gas transfer velocities in natural seawater samples. Ocean Sci. 10, 587–600 (2014).

Longhurst, A. Seasonal cycles of pelagic production and consumption. Progress. Oceanogr. 36, 77–167 (1995).

Wurl, O., Stolle, C., Van Thuoc, C., Thu, P. T. & Mari, X. Biofilm-like properties of the sea surface and predicted effects on air–sea CO2 exchange. Progress. Oceanogr. 144, 15–24 (2016).

Thornton, D. C. O. Dissolved organic matter (DOM) release by phytoplankton in the contemporary and future ocean. Eur. J. Phycol. 49, 20–46 (2014).

Wanninkhof, R. et al. Gas transfer experiment on Georges Bank using two volatile deliberate tracers. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 98, 20237–20248 (1993).

Wanninkhof, R. et al. Gas exchange, dispersion, and biological productivity on the West Florida Shelf: results from a Lagrangian tracer study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 24, 1767–1770 (1997).

Hoppe, H. G., Gocke, K., Koppe, R. & Begler, C. Bacterial growth and primary production along a north–south transect of the Atlantic Ocean. Nature 416, 168–171 (2002).

Bell, T. G. et al. Estimation of bubble-mediated air–sea gas exchange from concurrent DMS and CO2 transfer velocities at intermediate-high wind speeds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 9019–9033 (2017).

Blomquist, B. W. et al. Wind speed and sea state dependencies of air–sea gas transfer: results from the High Wind Speed Gas Exchange Study (HiWinGS). J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 8034–8062 (2017).

Patro, R., Leifer, I. & Bowyer, P. Better bubble process modeling: improved bubble hydrodynamics parameterization. in Gas Transfer at Water Surfaces (ed. Donelan, M. A.) 315–320 (AGU, Washington, DC, 2013).

Schlitzer, R. Ocean Data View (ODV, 2018); https://odv.awi.de

Cunliffe, M. W. O. Guide to Best Practices to Study the Ocean’s Surface (Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, Plymouth, 2014).

Garrett, W. D. Collection of slick-forming materials from the sea surface. Limnol. Oceanogr. 10, 602–605 (1965).

Cunliffe, M. et al. Dissolved organic carbon and bacterial populations in the gelatinous surface microlayer of a Norwegian fjord mesocosm. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 299, 248–254 (2009).

Cosovic, B. & Vojvodic, V. The application of AC polarography to the determination of surface-active substances in sea-water. Limnol. Oceanogr. 27, 361–368 (1982).

Tayler, J. R. An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements (University Science Books, Sausalito, 1996).

Welschmeyer, N. A. Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll-a in the presence of chlorophyll-B and pheopigments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39, 1985–1992 (1994).

Ashton, I. G., Shutler, J. D., Land, P. E., Woolf, D. K. & Quartly, G. D. A sensitivity analysis of the impact of rain on regional and global sea–air fluxes of CO2. PLoS ONE 11, e0161105 (2016).

Shutler, J. D. et al. FluxEngine: a flexible processing system for calculating atmosphere–ocean carbon dioxide gas fluxes and climatologies. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 33, 741–756 (2016).

Wrobel, I. & Piskozub, J. Effect of gas-transfer velocity parameterization choice on air–sea CO2 fluxes in the North Atlantic Ocean and the European Arctic. Ocean Sci. 12, 1091–1103 (2016).

Woolf, D. K., Land, P. E., Shutler, J. D., Goddijn-Murphy, L. M. & Donlon, C. J. On the calculation of air–sea fluxes of CO2 in the presence of temperature and salinity gradients. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 1229–1248 (2016).

Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea–air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 554–577 (2009).

Reynolds, R. W. et al. Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. J. Clim. 20, 5473–5496 (2007).

Donlon, C. J. et al. Toward improved validation of satellite sea surface skin temperature measurements for climate research. J. Clim. 15, 353–369 (2002).

Goddijn-Murphy, L. M., Woolf, D. K., Land, P. E., Shutler, J. D. & Donlon, C. The OceanFlux Greenhouse Gases methodology for deriving a sea surface climatology of CO2 fugacity in support of air–sea gas flux studies. Ocean Sci. 11, 519–541 (2015).

Dlugokencky, E. J. et al. Atmospheric carbon dioxide dry air mole fractions from the NOAA ESRL Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network, 1968–2016 Version 2017-07-28 (NOAA, 2017).

Weiss, R. F. Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: the solubility of a non-ideal gas. Mar. Chem. 2, 203–215 (1974).

Bigdeli, A., Loose, B., Nguyen, A. T. & Cole, S. T. Numerical investigation of the Arctic ice–ocean boundary layer and implications for air–sea gas fluxes. Ocean Sci. 13, 61–75 (2017).

Galgani, L., Piontek, J. & Engel, A. Biopolymers form a gelatinous microlayer at the air–sea interface when Arctic sea ice melts. Sci. Rep. 6, 29465 (2016).

BIPM. Evaluation of measurement data—guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement. JCGM 100, 2008 (2008).

Acknowledgements

AMT director A. Rees (Plymouth Marine Laboratory) enabled our participation in JCR cruise 303 (AMT24) and the authors thank the crew and scientists who supported our work. The authors thank the British Oceanographic Data Centre (BODC) for calibrated ancillary data, and J. Barnes (Newcastle) and J. Bischoff (Lyell Centre) for laboratory support and cruise mobilization. This work was supported by grants from the Leverhulme Trust to R.C.U.G. (RPG-303) and the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) to R.C.U.G. (NE/K00252X/1) and J.D.S. (NE/K002511/1). Both NERC grants are components of RAGNARoCC (Radiatively Active Gases from the North Atlantic Region and Climate Change), which contributes to NERC’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Feedbacks programme (www.nerc.ac.uk/research/funded/programmes/greenhouse). J.D.S. and I.A. acknowledge additional support from the European Space Agency (grant 4000112091/14/I-LG). R.P. acknowledges support from T. Wagner. This study is a contribution to the international IMBeR project and was supported by UK NERC National Capability funding to Plymouth Marine Laboratory and the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton. This is contribution no. 324 of the AMT programme.

The Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT) is an international effort, endorsed by the International Ocean Carbon Coordination Project (IOCCP), the Surface Ocean Lower Atmosphere Study (SOLAS) and the Integrated Marine Biosphere Research (IMBeR) programme, to deliver a uniformly quality-controlled surface ocean CO2 database. The many researchers and funding agencies responsible for the collection of data and quality control are thanked for their contributions to SOCAT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P. performed the gas exchange experiments. B.S. provided the surfactant measurements. I.A. and J.D.S developed the FluxEngine analysis and ran the model. R.P. and R.C.U.G. conceived the study. All authors discussed the results and developed the project and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Data Tables 1–4

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pereira, R., Ashton, I., Sabbaghzadeh, B. et al. Reduced air–sea CO2 exchange in the Atlantic Ocean due to biological surfactants. Nature Geosci 11, 492–496 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0136-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0136-2

This article is cited by

-

Visual anemometry for physics-informed inference of wind

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

The possibilities of voltammetry in the study reactivity of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in natural waters

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2023)

-

Assessment on the distributions and exchange of anionic surfactants in the coastal environment of Peninsular Malaysia: A review

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

-

Natural variability in air–sea gas transfer efficiency of CO2

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Distinct air–water gas exchange regimes in low- and high-energy streams

Nature Geoscience (2019)