Abstract

Reaching net-zero targets requires massive increases in wind energy production, but efforts to build wind farms can meet stern local opposition. Here, inspired by related work on vaccinations, we examine whether opposition to wind farms is associated with a world view that conspiracies are common (‘conspiracy mentality’). In eight pre-registered studies (collective N = 4,170), we found moderate-to-large relationships between various indices of conspiracy beliefs and wind farm opposition. Indeed, the relationship between wind farm opposition and conspiracy beliefs was many times greater than its relationship with age, gender, education and political orientation. Information provision increased support, even among those high in conspiracy mentality. However, information provision was less effective when it was presented as a debate (that is, including negative arguments) and among participants who endorsed specific conspiracy theories about wind farms. Thus, the data suggest preventive measures are more realistic than informational interventions to curb the potentially negative impact of conspiracy beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

For many countries, achieving net-zero targets will require an extraordinary ramping up of energy sourced from wind. For example, when Princeton University modelled a pathway to net-zero emissions in the United States that relied entirely on renewable energy, they calculated it would require over 1 million square kilometres of land, roughly the size of Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, Illinois and Louisiana combined1. In Germany, the current government agreed to designate 2% of the country’s landscape for the construction of wind farms2. The scale of escalation suggests a fundamental transformation in people’s exposure to—and relationship with—wind farms in the future.

Existing research suggests that people are positive about wind energy in the abstract, but when it comes to actually establishing wind farms in local communities, there has been substantial resistance, to the point where many proposals have been killed off3. In some cases, resistance has been amplified by organized campaigns of disinformation (for example, about negative health consequences of wind farms)4,5. These pockets of resistance might be early red flags for what other nations may soon experience once wind farms become a more visible and salient part of people’s lived experiences. Just as nations will need to massively ramp up investment in wind farms to meet renewable energy targets, so too does the scientific community need to ramp up its ability to anticipate (and defuse) factors that lead to wind farm resistance.

In other domains, it has long been understood that people’s attitudes towards science and emerging technologies are shaped by their cultural and ideological world views6,7,8,9. One world view that has become a particular focus of attention is what we refer to here as ‘conspiracy mentality’, the notion that it is commonplace for groups of elites with bad intentions to conduct elaborate hoaxes on the public and to do so in near-perfect secrecy10,11,12. People who subscribe to this world view are more likely to be sceptical about climate science and (in particular) about vaccines9,13,14. This general, relatively stable world view manifests in beliefs in specific conspiracy theories regarding concrete situations or topics15. In many Western countries, for example, up to a quarter of variance in people’s attitudes towards vaccines can be explained merely by knowing whether they believe Princess Diana was murdered or the 9/11 attacks were an inside job13. Knowing the powerful role of conspiracy mentality and specific conspiracy beliefs in understanding attitudes towards other large-scale social initiatives, it seems overdue to examine its role in people’s attitudes towards wind farms.

In this Article, we report research in which we examine the relationship between several indicators of conspiracy beliefs and opposition to wind farms. In addition, we test experimentally the effects of different types of information provision on participants’ attitudes. We find that conspiracy mentality explains a large portion of people’s resistance to vote in favour of a potential wind farm in their community. Believing in a specific conspiracy theory around the construction of the wind farm does so to an even larger degree. Informing people about the benefits of the wind farm has a considerable positive effect on their intentions to vote for the wind farms, particularly among those with a strong conspiracy mentality. These effects are smaller when people are also provided with counterarguments or when they believe in a specific conspiracy theory about the wind farm. Overall, our research suggests that conspiracy beliefs play a major role in understanding resistance to wind farms and sheds light on how to counteract this opposition.

Conspiracy mentality and resistance to wind farms

There are at least two reasons to assume that wind farms are vulnerable to being caught in the net of suspicion implied by a conspiracy mentality. First, conspiracy theories have long circulated about wind turbines, even if this phenomenon has largely evaded academic attention. For example, despite dozens of academic studies indicating that wind farms pose no threat to human health16,17, conspiracy theories persist that they contribute to congenital abnormalities, fatigue and/or cancer, claims that have been propagated by anti-wind farm lobby groups and echoed by senior politicians including former US President Donald Trump5,18. More mainstream conspiracy theories assert that politicians are pushing ineffective technologies for cynical financial reasons. High conspiracy mentality predisposes people to believe such misinformation15.

Second, attitudes towards wind farms appear to be trust sensitive; analyses of surveys, experiments and interview data converge to argue that support for wind farms is primarily shaped by people’s sense of equity, integrity-based trust, justice and fairness19,20,21. Given that conspiracy mentality is characterized by distrust of elites12,22—and given that trust in the involved parties (for example, local governments) is a key driver of the acceptance of wind farms19,20—it seems reasonable to expect that people with a stronger conspiracy mentality might be more opposed to the construction of wind farms in their community. Similarly, wind farms could be rejected because wind energy is largely accepted by societies, and holding views in counterpoint to the mainstream is related to conspiracy mentality23,24.

We tested this prediction in eight pre-registered studies in Germany (collective N = 4,170). The German context is ideally suited to examine this question because of Germany’s leading role in wind farm technology; in 2020, it produced 131 TWh (103.7 TWh onshore), which amounts to 23.7% of the country’s gross energy consumption25. Germany ranks third in terms of installed wind power capacities26, and the current government has envisaged to nearly double the capacity until 203027. However, there have been examples of citizen resistance towards wind farms in Germany28,29, and occasionally, such protests have been seized upon by far-right populist parties as part of a broader sentiment of alienation and resentment in coal mining communities30. In short, policy around wind energy is a major topic in Germany, one that is discussed both at the grassroots level and in official political debates. Understanding the psychology of wind farm resistance in an early adopter such as Germany will provide important clues to what might occur in other countries seeking rapid decarbonization.

We asked participants to imagine a scenario in which the construction of five wind turbines was planned close to their community and to indicate the likelihood (0–100%) with which they would vote in favour of the wind turbines in a local referendum. In addition, we measured participants’ conspiracy mentality (for example, ‘Politicians and other leaders are nothing but the string puppets of powers operating in the background’; ‘Most people do not recognize to what extent our life is determined by conspiracies that are concocted in secret’)12. None of the items used in this measure referred to wind farms or energy policies.

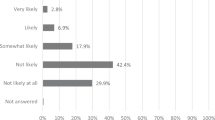

Studies 1–7 were conducted with convenience samples of German adults. When aggregated, they revealed a strong negative correlation, r(2,055) = −0.34, p < 0.001, such that acceptance of wind turbines was lower among those with a stronger conspiracy mentality. To obtain a more accurate estimation of this relationship in the German population, Study 8 (N = 2,115) used a nationally quota-balanced sample regarding gender, age, education and state. We also controlled for political orientation, given that conspiracy mentality is particularly strong among conservatives in Germany31. On average, participants in this sample indicated modestly high support for the building of wind turbines (mean (M) = 64.95, standard deviation (SD) = 31.30). However, supporting our prediction, a higher conspiracy mentality strongly predicted lower support for the building of wind turbines, unstandardized regression coefficient (b) = −7.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−8.90; −6.98], Student’s t(2,106) = −16.23, p < 0.001, Pearson correlation coefficient (r) = −0.33, over and above age, gender, education, and political orientation (Fig. 1). This means that conspiracy mentality (M = 4.01, SD = 1.34) was associated with lower support for wind turbines by 11 percentage points per standard deviation (for example, from 65% to 54% from people with average conspiracy mentality to people with 1 SD above average).

Standardized regression coefficients β (centre) with error bars indicating the 95% CI for each predictor from a multiple linear regression with willingness to vote in favour of constructing wind turbines close to one’s hometown as criterion (N = 2,113).

Effects of providing arguments in favour of wind farms

The substantial and robust relationship between conspiracy mentality and rejection of wind farms raises the question of how this resistance might be reduced. Usually, there are campaigns preceding local referenda in which stakeholders provide information supporting their position to the local population. Indeed, there is initial evidence that such communication can help increase wind farm acceptance3,32. One important factor that was identified in these studies was the local authority’s support for the wind project. It is, however, questionable whether such support would be beneficial to persuading people with a conspiracy mentality, as there is some evidence that they react defensively towards communication provided by sources of power33.

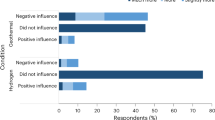

In Studies 1–8, we also tested whether communication that provides arguments in favour of wind turbines would increase likelihood of voting for wind turbines and whether this depended on participants’ conspiracy mentality. We provided participants in one experimental condition with a leaflet (written by the authors but inspired by real information campaigns; Supplementary Methods) about hypothetical planned wind turbines said to be issued by the local municipality. The leaflet featured arguments about, for instance, potential for reducing carbon emissions, security of energy supply and opportunities for financial profit of citizens and municipality. In a merged analysis across all studies (N = 4,170), moderated multiple regressions showed that providing pro arguments about wind turbines significantly increased participants’ willingness to vote in favour of constructing them, compared with a no-information control, b = 4.66, 95% CI [3.74; 5.57], t(4,164) = 9.98, p < 0.001. Interestingly, an interaction with conspiracy mentality emerged, b = 0.76, 95% CI [0.05; 1.46], t(4,164) = 2.11, p = 0.035, such that the effect of communication was greatest among those with a stronger conspiracy mentality (Fig. 2). In other words, a communication that took participants roughly 2 minutes (median 112 seconds) to read was highly effective in reducing the negative relationship between conspiracy mentality and wind farm acceptance.

Willingness to vote in favour of constructing the wind turbines as a function of conspiracy mentality (7-point rating scale from 1 ‘do not agree at all' to 7 = ‘fully agree’ with higher scores indicating stronger conspiracy mentality) and communication (only pro versus balanced versus no communication) from an aggregated analysis across all studies (nonly pro = 1,578, nbalanced = 1,044, nno communication = 1,548). Lines represent estimates per condition, shaded areas the ± 1 standard error margin. The solid vertical line represents the sample mean of conspiracy mentality; the dotted vertical lines mark one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively.

To probe the robustness of these effects, Study 2 examined what would happen if the information was provided by industry (as opposed to government); the effects reported above remained unchanged (Supplementary Table 7). In Study 3, we examined what happens if the referendum was initiated by local opponents of the project (as opposed to supporters). Again, the main effects of conspiracy mentality and information provision were not moderated by this manipulation (Supplementary Table 7). Thus, our data provide stable evidence that communication in favour of building wind turbines increases likelihood of voting for it—especially among those with strong conspiracy mentality.

A subset of studies (Studies 4–6, 8) included an additional experimental condition in which participants received arguments in favour of the wind turbines but also the same number of contra arguments. Here we sought to increase ecological validity because in real-world contexts, people are exposed to pro and contra arguments as part of debate. These studies also spoke to a theoretical controversy. On the basis of the classical Yale model of persuasion, this kind of two-sided communication could be considered particularly trustworthy and effective34, although subsequent research has shown inconsistent results35.

Results revealed that the effectiveness of pro arguments was significantly reduced when counterarguments were also included, b = −3.19, 95% CI [−4.21; −2.17], t(4,164) = −6.13, p < 0.001. Still, receiving both pro and contra arguments slightly increased willingness to vote in favour of wind turbines compared with receiving no communication, b = 1.47, 95% CI [0.45; 2.49], t(4,164) = 2.81, p = 0.005 (Fig. 2). It is reassuring to know that providing pro and contra arguments simultaneously does not make things worse—especially in light of previous research showing that denialists’ rhetoric reduces beliefs in anthropogenic climate change36. Still, these studies demonstrate that stakeholders who want to convince the local population of wind turbines’ merits might have a harder time when facing other stakeholders with competing interests.

Specific conspiracy beliefs

Results reported so far are based on a measure of conspiracy mentality; that is, the general propensity to believe in conspiracy theories. As outlined above, this needs to be distinguished from believing a specific conspiracy theory within a given context15; in this case, conspiracies surrounding the referendum that participants were evaluating. To examine specific conspiracy beliefs, we included six items (for example, ‘The municipality withholds important information that would speak against the construction of the wind turbines’; ‘The municipality has made secret arrangements with the executing energy company so that both would profit financially from the construction of the wind turbines’). These beliefs were relatively widespread in the nationally quota-balanced sample; 26% of participants scored above the scale midpoint (M = 3.23, SD = 1.39; Fig. 3).

a,b, Distribution of specific conspiracy beliefs (7-point rating scale from 1 ‘do not agree at all’ to 7 ‘fully agree’ with higher scores indicating stronger specific conspiracy beliefs)(a) and correlation between specific conspiracy beliefs and willingness to vote in favour of the wind turbines (b) (N = 2,115). The line represents estimates of voting intention; the shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval.

These conspiracy beliefs were even more strongly associated with lower support for wind turbines than conspiracy mentality (again controlling for demographic variables and political orientation), b = −11.51, 95% CI [−12.33; −10.69], t(2,106) = −27.45, p < 0.001, r = −0.51 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Support for wind turbines was by approximately 16 percentage points lower with each 1 SD increase in specific conspiracy beliefs. When adding specific conspiracy beliefs and conspiracy mentality simultaneously to the regression, conspiracy mentality predicted substantially less variance, b = −1.25, 95% CI [−2.32; −0.17], t(2,105) = −2.28, p = 0.023, than the specific belief, b = −10.83, 95% CI [−11.84; −9.82], t(2,105) = −21.01, p < 0.001. This supports the idea that specific conspiracy beliefs are manifestations of conspiracy mentality in concrete contexts15.

Providing arguments in favour of building the wind turbines still enhanced support among those strongly endorsing specific conspiracy beliefs, b = 2.86, 95% CI [1.95; 3.76], t(3,747) = p < 0.001, but only about half of the extent to which it did for those with a strong conspiracy mentality. However, in the studies for which positive information was balanced with negative information, there was no reliable improvement in voting intentions among those with strong specific conspiracy beliefs, b = 0.54, 95% CI [−0.42; 1.50], t(3,747) = 1.10, p = 0.270. Although there was no evidence that information provision caused backfire effects among those high in conspiracy beliefs, it is sobering that the positive effects of supportive evidence could be neutralized by counterarguments.

Discussion

A rapid increase in the number of wind farms is needed to reduce carbon emissions worldwide and to slow climate change. The current research revealed a factor that could be a major barrier to achieving this goal: conspiracy beliefs. We showed that the stronger people’s conspiracy mentality, the less likely they were to vote for the construction of wind turbines close to their community in a potential referendum. It is revealing to examine the relative strength in predictive value of conspiracy mentality compared with other variables (percentage of variance explained in voting intentions can be calculated by squaring the correlations). Conspiracy mentality explained five times more variance compared with political orientation and around 20 times more variance than age, gender, education and state in the nationally quota-balanced sample.

Notably, over a quarter of this sample scored high on endorsement of specific conspiracy theories about the wind farm construction. When considering participants’ beliefs in these specific conspiracy theories, the relationship was even stronger, explaining at least 25 times more variance in voting intentions compared with the other variables. These findings suggest that a predisposition to believe conspiracy theories is a barrier to wind farm acceptance and even more so when this general predisposition crystallizes into believing specific conspiracy theories about the authorities’ motives.

Longitudinal research provided evidence for the causal effects of conspiracy beliefs on vaccination and countermeasures during the COVID-19 pandemic37,38,39. It therefore also seems reasonable to assume a similar causal pathway here: that participants start with a general conspiracy mentality, which takes shape in the form of specific conspiracy beliefs, which then directly affect voting intentions15 (but see ref. 40). However, our studies are not designed to test this causal claim. Longitudinal studies may be useful going forward in terms of shoring up the case for a causal relationship between conspiracy beliefs and wind farm resistance.

Our studies also investigated potential methods of intervention and offered good news: people can be reached via public communication that stresses the benefits of wind farms. Overall, and particularly among those holding a strong conspiracy mentality, willingness to vote for the construction of wind turbines could be enhanced by providing pro arguments (for example, potential to reduce emissions). This communication was still effective (but to a lesser degree) among people who strongly believed in specific conspiracy theories around the wind turbines. This adds substance to the limited body of research investigating public communication about wind energy projects3,32. It shows that providing arguments early on (ideally before specific conspiracy beliefs evolve) is important to increase wind farm acceptance and to counter the negative phenomena associated with conspiracy mentality. Drawing on research on conspiracy mentality and vaccination, such communication might be even more effective when it comes from people’s close social environment (compared with authorities)41 as peer influence also shapes energy-related behaviours42. The positive effect of information provision is reassuring given discussion in other literature that in polarized environments, information about science can cause backfire effects43,44 and in the context of a general scepticism in the scholarly community that conspiracy theorists can be ‘reached’ through information provision alone45,46.

However, some of the reported studies examined effects of information provision under more realistic conditions, that is, when people had access to both arguments in favour of and against building the wind turbines. These results gave less reason for optimism. On one hand, balanced communication was still somewhat effective among those with a strong conspiracy mentality. On the other hand, it remained ineffective among those who strongly believed in a specific conspiracy theory around the referendum. One way of reaching these people might be prevention rather than intervention.

Preventive approaches against conspiracy beliefs and their negative correlates have already been tested in the literature. Most prominently, inoculation or pre-bunking strategies are effective in reducing people’s susceptibility to misinformation and conspiracy theories46,47,48. That is, providing people with a weak dose of false information up front, or making them aware of the strategies that are used by conspiracy theorists, can prepare them to resist misinformation. Likewise, providing detailed explanations about an issue before conspiracy theories spread can increase people’s resistance against these narratives49,50. Such strategies could be applied in the domain of wind farm acceptance as well.

Embedded in the German context, the current research focused on a single country in which wind energy already plays a major role. But given their pledge to reach net-zero emissions, other countries will probably be in a similar position of increasing wind energy in the future. Investigating the role of conspiracy mentality in shaping citizens’ support for wind farms in a country on the forefront of implementing this technology provides valuable insights for other countries on steep decarbonization trajectories.

Methods

Participants and study design

We pre-registered all studies on aspredicted.org (Study 1: https://aspredicted.org/46at3.pdf; Study 2: https://aspredicted.org/rn59j.pdf; Study 3: https://aspredicted.org/z3by8.pdf; Study 4: https://aspredicted.org/pg5st.pdf; Study 5: https://aspredicted.org/gt893.pdf; Study 6: https://aspredicted.org/vv9wi.pdf; Study 7: https://aspredicted.org/mq4ut.pdf; Study 8: https://aspredicted.org/m295a.pdf).

In total, N = 4,170 participants took part in our studies (Study 1: n = 142; Study 2: n = 275; Study 3: n = 361; Study 4: n = 416; Study 5: n = 419; Study 6: n = 249; Study 7: n = 193; Study 8: n = 2,115). Three hundred and one additional participants were excluded based on pre-registered criteria (below). The sample sizes of all single studies were determined to be able to detect at least a small effect (f² = 0.05) in a multiple regression analysis with a statistical power of 80% at a significance level of 5%. Demographic data of the participants are presented in the Supplementary Table 1. All studies were conducted online with German adults who were recruited via participant platforms (Clickworker: Studies 1, 2, 3 and 7; Prolific: Studies 5 and 6). Study 8 was run by a recruiting agency (Respondi) to collect a nationally quota-balanced sample (in terms of age, gender, education and state). Payment of participants differed between studies due to different survey lengths but was generally above the statutory minimum wage in the country (except Study 8 for which the recruiting agency determined the payment).

As noted in our pre-registrations, we included participants in our analyses if they fulfilled the following criteria: were at least 18 years old, spoke German fluently (because study materials were largely text based), did not fail the attention check items included in the survey, did not take the survey multiple times, were not psychology students (because they are familiar with psychological study procedures and might be suspicious about our hypotheses) and were not identified as statistical outliers in the main analysis (based on studentized deleted residuals, see pre-registrations). In Study 8, however, we did not apply the language and psychology criteria (as pre-registered) to not compromise the representativeness of the sample. For the same reason, we did not analyse the data of 75 participants in Study 8 who were additionally recruited due to a sampling error of the recruiting agency. On the basis of these criteria N = 301 participants from the original samples were excluded (Study 1: n = 10; Study 2: n = 24; Study 3: n = 36; Study 4: n = 34; Study 5: n = 28; Study 6: n = 22; Study 7: n = 4; Study 8: n = 143). The applied exclusions did not change the results in a way that would lead to different conclusions than the ones we presented in the main text.

Procedure and measures

The experiments were implemented via the Qualtrics survey software. The procedure and measures were nearly identical across all studies. Slight differences across studies were due to the specific research questions addressed in each study. After giving informed consent at the outset of the studies, participants were asked to imagine that there were plans to build five wind turbines close to their communities and that there was a referendum to decide on these plans. Participants were aware that the referendum and the wind farms were fictitious.

Then, participants were randomly assigned to different experimental conditions. Two of these conditions were identical in all studies: the only pro condition and the no communication condition. In the only pro condition, participants were told that the municipality published a leaflet to inform citizens about the planned wind turbines and that the information was based on independent experts’ reviews. The leaflet contained seven arguments in favour of building the wind turbines (Supplementary Methods for details). Participants in the no communication condition did not receive such a leaflet but directly proceeded with the survey. Besides these two basic experimental conditions, several studies contained additional experimental conditions (Supplementary Table 2 for an overview). In Study 2, we added a condition in which the leaflet (containing only pro arguments) ostensibly stemmed from the operating energy company (instead of the municipality) to manipulate vested interests (Supplementary Table 8 for manipulation check results). Studies 4 and 5 contained an additional experimental condition in which participants received an equal number of arguments opposed to building the wind turbines in alternation with the pro arguments. These counterarguments were said to be raised by a local initiative opposing the wind turbines. In Studies 6 and 8, we presented the same balanced arguments, but here they were presented by the same source (that is, the municipality bringing up both sides but eventually refuting the counterarguments). We refer to these latter two conditions as balanced conditions.

Afterwards, participants were asked to indicate their voting intentions as our main dependent variable. The concrete wording of the referendum was ‘Are you in favour of the municipality leasing land for the purpose of constructing and operating five wind turbines?’. Participants’ response options ranged from ‘I would definitely vote no’ (0%) to ‘I would definitely vote yes’ (100%). In Study 3, we added two experimental conditions (one presenting only pro and one presenting no communication) in which the framing of the referendum was reversed; that is, asking whether participants were against (instead of in favour of) constructing the wind turbines. In all studies, we included further measures for exploratory reasons (Supplementary Table 3 for a complete list of measures). In Studies 3–8, we measured belief in specific conspiracy theories about the referendum with a six-item scale. Conspiracy mentality was always assessed at the end of the survey with a 12-item scale12. Both measures were not substantially affected by the preceding experimental manipulation (conspiracy mentality: effect size eta-squared (η²) = 0.002; specific conspiracy beliefs: η² = 0.01). Thus, we were successful in our aim to not activate conspiracy theories with our manipulation. Demographic information including age, gender and education was then retrieved before debriefing participants about the purpose of the study.

Analysis strategy

To analyse the relationship between conspiracy mentality (or specific conspiracy beliefs) and the acceptance of wind turbines in the nationally quota-balanced sample (that is, Study 8), we conducted linear multiple regression analysis. Conspiracy mentality was included as predictor and age, gender (+1 female, −1 male), education (1 = low, 2 = medium, 3 = high), political orientation (from 1 ‘left’ to 7 ‘right’) and state. We sorted the 16 German federal states according to their installed onshore wind power capacity divided by the size of the state. Then, we split the states into two groups representing the lower (−1) and the upper half (+1) in terms of installed capacity per km² resulting in comparable numbers of participants (Supplementary Table 4 for the rank order of the states). To be able to include gender as a covariate in these analyses, we removed the two participants who reported their gender as ‘other’.

To examine the impact of the pro arguments versus balanced arguments, we report merged analyses across all studies in the main text (that is, we combined the data of all studies into one large dataset). This was possible because all studies shared the crucial properties of the experimental design and used the same procedure and measures. Such an aggregated way of analysing the data has the advantage of maximizing statistical power to detect the true effect of interest with smaller confidence intervals51. It also allows for presenting all the data we collected in an efficient and transparent manner (that is, we report all studies that we conducted to test the research questions). The reason for conducting several smaller studies partly lies in the fact that the first results were counter to our theory-driven expectations (pre-registrations), which led us to replicate them in subsequent studies and to test several plausible moderators (as outlined in the main text). The final study served to confirm these results with a large and nationally quota-balanced sample.

The merged analyses followed the pre-registration of Study 8 and contained three experimental conditions (communication: only pro versus balanced versus no communication). In a first linear multiple regression analysis, we tested the impact of the only pro (versus no communication) condition on willingness to vote for the construction of the wind turbines. To this end, and following the recommendations of Aiken and West52, we used orthogonal contrasts to code the experimental conditions (focal contrast: +1 only pro, 0 balanced, −1 no communication; residual contrast: −1 only pro, +2 balanced, −1 no communication) and mean-centred the continuous predictor conspiracy mentality. In addition, the interaction terms of both contrasts and mean-centred conspiracy mentality were included as predictors. Following the same principal procedure, we conducted two more linear multiple regression analyses to examine the effectiveness of the balanced communication. These two regression analyses used different contrasts to compare the balanced with the only pro condition (focal contrast: −1 only pro, +1 balanced, 0 no communication; residual contrast: +1 only pro, +1 balanced, −2 no communication) and the balanced with the no communication condition (focal contrast: 0 only pro, +1 balanced, −1 no communication; residual contrast: +2 only pro, −1 balanced, −1 no communication). All statistical tests were two sided. Analyses with specific conspiracy beliefs as predictor were carried out analogously. Complete results of these regression analyses and the pre-registered analyses for all individual studies can be found in the Supplementary Notes. All analyses were carried out with IBM SPSS v25. The research data are publicly available via PsychArchives53.

Ethics

All studies were conducted in line with the ethical guidelines for psychological research of the American Psychological Association and the German Research Foundation and received ethical approval by the institutional ethics board of the Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien (Tübingen, Germany; LEK 2019/001).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings reported in the manuscript and the source data of Figs. 1–3 are publicly available via PsychArchives (https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.8253).

Code availability

The code used to analyse the datasets is publicly available via PsychArchives (https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.8252).

References

Larson, E. et al. Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts Report (Princeton University, 2021).

Bundesregierung (Federal Government). Koalitionsvertrag 2021 (Coalition Agreement 2021) https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/1990812/04221173eef9a6720059cc353d759a2b/2021-12-10-koav2021-data.pdf (2021).

Enevoldsen, P. & Sovacool, B. K. Examining the social acceptance of wind energy: practical guidelines for onshore wind project development in France. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 53, 178–184 (2016).

Crichton, F., Chapman, S., Cundy, T. & Petrie, K. J. The link between health complaints and wind turbines: support for the nocebo expectations hypothesis. Front. Public Health 2, 220 (2014).

Chapman, S., St. George, A., Waller, K. & Cakic, V. The pattern of complaints about Australian wind farms does not match the establishment and distribution of turbines: support for the psychogenic, ‘communicated disease’ hypothesis. PLoS ONE 8, e76584 (2013).

Kahan, D. M., Braman, D., Slovic, P., Gastil, J. & Cohen, G. Cultural cognition of the risks and benefits of nanotechnology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 87–90 (2009).

Kahan, D. M. Fixing the communications failure. Nature 463, 296–297 (2010).

Kahan, D. M. et al. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 732–735 (2012).

Lewandowsky, S., Gignac, G. E. & Vaughan, S. The pivotal role of perceived scientific consensus in acceptance of science. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 399–404 (2013).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M. & Cichocka, A. The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 26, 538–542 (2017).

Goertzel, T. Belief in conspiracy theories. Polit. Psychol. 15, 731–742 (1994).

Imhoff, R. & Bruder, M. Speaking (un-)truth to power: conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. Eur. J. Pers. 28, 25–43 (2014).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A. & Fielding, K. S. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: a 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 37, 307–315 (2018).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A. & Fielding, K. S. Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 614–620 (2018).

Imhoff, R., Bertlich, T. & Frenken, M. Tearing apart the ‘evil’ twins: a general conspiracy mentality is not the same as specific conspiracy beliefs. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 46, 101349 (2022).

McCunney, R. J. et al. Wind turbines and health: a critical review of the scientific literature. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 56, e108–e130 (2014).

Knopper, L. D. & Ollson, C. A. Health effects and wind turbines: a review of the literature. Environ. Health 10, 78 (2011).

Bump, Philip. Trump claims that wind farms cause cancer for very Trumpian reasons. Washington Post (3 April 2019).

Hall, N., Ashworth, P. & Devine-Wright, P. Societal acceptance of wind farms: analysis of four common themes across Australian case studies. Energy Policy 58, 200–208 (2013).

Liu, L., Bouman, T., Perlaviciute, G. & Steg, L. Effects of competence- and integrity-based trust on public acceptability of renewable energy projects in China and the Netherlands. J. Environ. Psychol. 67, 101390 (2020).

Wolsink, M. Wind power implementation: the nature of public attitudes: equity and fairness instead of ‘backyard motives’. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 11, 1188–1207 (2007).

Lamberty, P. & Imhoff, R. Powerful pharma and its marginalized alternatives? Effects of individual differences in conspiracy mentality on attitudes toward medical approaches. Soc. Psychol. 49, 255–270 (2018).

Pummerer, L. Belief in conspiracy theories and non-normative behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 47, 101394 (2022).

Lantian, A., Muller, D., Nurra, C. & Douglas, K. M. ‘I know things they don’t know!’ The role of need for uniqueness in belief in conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. 48, 160–173 (2017).

Renewable energy. BMWK https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/EN/Dossier/renewable-energy.html (2022).

Lebedys, A. et al. Renewable Energy Statistics 2022 (IRENA, 2022); https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2022/Jul/IRENA_Renewable_energy_statistics_2022.pdf

Federal Minister Robert Habeck says Easter package is accelerator for renewable energy as the Federal Cabinet adopts key amendment to accelerate the expansion of renewables. BMWK https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2022/04/20220406-federal-minister-robert-habeck-says-easter-package-is-accelerator-for-renewable-energy.html (2022).

Arifi, B. & Winkel, G. Wind energy counter-conducts in Germany: understanding a new wave of socio-environmental grassroots protest. Environ. Polit. 30, 811–832 (2021).

Liebe, U. & Dobers, G. M. Decomposing public support for energy policy: what drives acceptance of and intentions to protest against renewable energy expansion in Germany? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 47, 247–260 (2019).

MacGillis, Alec. Can Germany show us how to leave coal behind? New Yorker (31 January 2022).

Imhoff, R. et al. Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 392–403 (2022).

Walker, B. J. A., Wiersma, B. & Bailey, E. Community benefits, framing and the social acceptance of offshore wind farms: an experimental study in England. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 3, 46–54 (2014).

Imhoff, R., Lamberty, P. & Klein, O. Using power as a negative cue: how conspiracy mentality affects epistemic trust in sources of historical knowledge. Personality Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 1364–1379 (2018).

Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L. & Kelley, H. H. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Studies of Opinion Change (Yale Univ. Press, 1953).

Crowley, A. E. & Hoyer, W. D. An integrative framework for understanding two-sided persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 20, 561–574 (1994).

McCright, A. M., Charters, M., Dentzman, K. & Dietz, T. Examining the effectiveness of climate change frames in the face of a climate change denial counter-frame. Top Cognit. Sci. 8, 76–97 (2016).

Oleksy, T. et al. Barriers and facilitators of willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19: role of prosociality, authoritarianism and conspiracy mentality. A four-wave longitudinal study. Personality Individual Differ. 190, 111524 (2022).

Bierwiaczonek, K., Kunst, J. R. & Pich, O. Belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories reduces social distancing over time. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 12, 1270–1285 (2020).

Pummerer, L. et al. Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Personality Sci. 13, 49–59 (2022).

Sutton, R. M. & Douglas, K. M. Conspiracy theories and the conspiracy mindset: implications for political ideology. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 34, 118–122 (2020).

Winter, K., Pummerer, L., Hornsey, M. J. & Sassenberg, K. Pro-vaccination subjective norms moderate the relationship between conspiracy mentality and vaccination intentions. Br. J. Health Psychol. 27, 390–405 (2022).

Wolske, K. S., Gillingham, K. T. & Schultz, P. W. Peer influence on household energy behaviours. Nat. Energy 5, 202–212 (2020).

Hart, P. S. & Nisbet, E. C. Boomerang effects in science communication: how motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Commun. Res. 39, 701–723 (2012).

Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. When corrections fail: the persistence of political misperceptions. Polit. Behav. 32, 303–330 (2010).

Hornsey, M. J. in Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19 (eds Jetten, J. et al.) 41–46 (SAGE Publishing, 2020).

Krekó, P. in Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories (eds Butter, M. & Knight, P.) 242–256 (Routledge, 2020).

Lewandowsky, S. & van der Linden, S. Countering misinformation and fake news through inoculation and prebunking. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 32, 348–384 (2021).

Ecker, U. K. H. et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 13–29 (2022).

Pummerer, L., Winter, K. & Sassenberg, K. Addressing COVID-19 vaccination conspiracy theories and vaccination intentions. Eur. J. Health Commun. 3, 1–12 (2022).

Jolley, D. & Douglas, K. M. Prevention is better than cure: addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 47, 459–469 (2017).

Curran, P. J. & Hussong, A. M. Integrative data analysis: the simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychol. Methods 14, 81–100 (2009).

Aiken, L. S. & West, S. G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions (Sage, 1991).

Winter, K., Hornsey, M. J., Pummerer, L. & Sassenberg, K. Dataset for: Anticipating and defusing the role of conspiracy beliefs in shaping opposition to wind farms. PsychArchives https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.8253 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, #SA800/17-1) awarded to K.S. and M.J.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S. and M.J.H. acquired funding for the studies. K.W. and K.S. conceptualized the study with feedback from L.P. and M.J.H. K.W. collected and analysed the data. K.W., L.P., K.S. and M.J.H. interpreted the data. K.W. drafted the article. All authors provided critical revision and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Energy thanks Roland Imhoff, Stephen Lewandowsky and Joseph Uscinski for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Notes 1–5, Tables 1–8 and Fig. 1.

Source data

Source Data For Fig. 1

Spreadsheet containing the source data of Fig. 1.

Source Data For Fig. 2

Spreadsheet containing the source data of Fig. 2.

Source Data For Fig. 3

Spreadsheet containing the source data of Fig. 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Winter, K., Hornsey, M.J., Pummerer, L. et al. Anticipating and defusing the role of conspiracy beliefs in shaping opposition to wind farms. Nat Energy 7, 1200–1207 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-022-01164-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-022-01164-w

This article is cited by

-

Realizing the full potential of behavioural science for climate change mitigation

Nature Climate Change (2024)