Abstract

Genes with sex-biased expression show a number of unique properties and this has been seen as evidence for conflicting selection pressures in males and females, forming a genetic ‘tug-of-war’ between the sexes. However, we lack studies of taxa where an understanding of conflicting phenotypic selection in the sexes has been linked with studies of genomic signatures of sexual conflict. Here, we provide such a link. We used an insect where sexual conflict is unusually well understood, the seed beetle Callosobruchus maculatus, to test for molecular genetic signals of sexual conflict across genes with varying degrees of sex-bias in expression. We sequenced, assembled and annotated its genome and performed population resequencing of three divergent populations. Sex-biased genes showed increased levels of genetic diversity and bore a remarkably clear footprint of relaxed purifying selection. Yet, segregating genetic variation was also affected by balancing selection in weakly female-biased genes, while male-biased genes showed signs of overall purifying selection. Female-biased genes contributed disproportionally to shared polymorphism across populations, while male-biased genes, male seminal fluid protein genes and sex-linked genes did not. Genes showing genomic signatures consistent with sexual conflict generally matched life-history phenotypes known to experience sexually antagonistic selection in this species. Our results highlight metabolic and reproductive processes, confirming the key role of general life-history traits in sexual conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Natural selection acts in distinct ways in males and females1,2,3,4,5,6 and this has resulted in pervasive differences in gene expression between the sexes1,6. However, sex-specific evolution is constrained because males and females share a common genome. An evolutionary tug-of-war driven by sexually antagonistic (SA) selection, where alleles favoured in females are disfavoured in males (and vice versa), is thus believed to generate genome-wide balancing and diversifying selection through widespread SA pleiotropy4 which will act to maintain genetic variation in fitness7. Genes with sex-biased gene expression (SBGs) do tend to show increased levels of standing genetic variation within populations, greater divergence between populations and rapid evolution across species8,9. Yet, the relative role of SA selection and genetic drift in such genome-wide patterns is not well established and most studies involve taxa where we lack an understanding of SA selection and SA phenotypes4,5. This is problematic because SBGs are predicted to experience relaxed purifying selection and this could in theory underlie the striking genetic features of SBGs3. Further, the form of selection may generally differ across classes of SBGs1: male-biased genes (MBGs) are expected to experience strong sexual selection while female-biased genes (FBGs) may be more subject to selection deriving from life-history trade-offs4. Genome-wide studies of genetic diversity in SBGs10 in species where SA phenotypes are well understood are needed to untangle concomitant processes affecting the evolution of SBGs4,5.

The seed beetle C. maculatus is an experimental model system for studies of SA selection and SA phenotypes. Males carry genital spines that cause injuries in females at mating and such spines are favoured in males by post-mating sexual selection11. Males transfer large amounts of ejaculate proteins to females at mating that are under sexual selection in males but some of which also have detrimental effects in females12. More importantly, phenotypic selection on shared life-history traits is SA such that females show lower optima for a pace-of-life syndrome: lower metabolic rate, prolonged juvenile development, larger body size, lower adult activity and a longer life-span13,14,15. In concordance, genotypes showing high female fecundity simultaneously tend to show low male fitness in this species16,17,18. Here, we sequenced, de novo assembled and annotated the genome of C. maculatus and then resequenced three divergent populations by sequencing pools of individuals (Pool-seq). Leaning on detailed information on gene expression in males and females19 and in-house annotations of focal gene sets (Supplementary Materials and Methods), we relate the degree and direction of sex-biased expression of almost 5,000 genes to measures of within-population genetic polymorphism and to indices of selection. We then identify candidate SA loci and ask whether these match known SA phenotypes.

Results and discussion

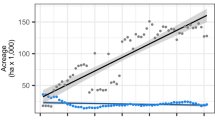

Genetic variation within populations was significantly higher in SBGs, whether estimated as single nucleotide polymorphism or as nucleotide diversity (π), and this was particularly pronounced for MBGs (Fig. 1a–c). In theory, increased genetic variation could be due to stronger balancing selection but relaxed purifying selection on SBGs could also contribute, since net screening of gene copies by selection is weaker if only one sex expresses a gene3. We used the ratio of substitution rates (p) at non-synonymous and synonymous sites (pN/pS) between segregating variants to infer the efficacy of purifying selection within populations20. The absolute value of pN/pS is somewhat difficult to interpret in this context but our observation of within-population pN/pS ratios for weakly SBGs of approximately 0.1 is at least consistent with simulations of strong purifying selection21. More importantly, that this ratio was significantly higher for more strongly SBGs (Fig. 1d) aligns very well indeed with the prediction that SBGs should experience relaxed purifying selection3. That this pattern was more pronounced for nucleotide diversity at non-synonymous sites (πns) than at synonymous sites (πs) (Fig. 1b versus 1c) is also consistent with this conclusion. Similar findings have previously been reported in flycatchers20, guppies10, birds9 and humans22. This strongly suggests that the unique properties of SBGs are at least in part due to relaxed purifying selection3.

Shown are mean (±95% bootstrap CI) metrics for genes showing different degrees of sex-biased expression, separately for the three populations (Brazil, blue; California, red; Yemen, green). Genes were grouped into quartiles based on their log2FC value, separately for FBGs and MBGs, resulting in eight bins in total. Sample size per bin is n = 592–656 genes. a, The density of polymorphism varied significantly across SBG categories (all P < 10−6). b,c, Nucleotide diversity also varied significantly across the SBG categories in synonymous (b; all P < 0.002) and, particularly, in non-synonymous (c; all P < 10–6) sites. These three different measures of DNA sequence variation all showed increased variation in SBGs, particularly in MBGs. d, The pattern of pN/pS across SBGs genes (all P < 10–6) was consistent with a history of strong negative selection in the least SBGs and relatively relaxed purifying selection with increasing sex-bias. e,f, Estimates of D also varied across SBG categories, significantly so in all populations when based on synonymous sites (e; Brazil: F7,4697 = 3.05, P = 0.004; California: F7,4877 = 4.97, P < 0.001; Yemen: F7,4851 = 5.66, P < 0.001) and in one population when based on non-synonymous sites (f; Brazil: F7,4011 = 1.76, P = 0.090; California: F7,4149 = 4.35, P < 0.001; Yemen: F7,4176 = 1.63, P = 0.122). Those SBG categories showing overall positive D with CIs not overlapping zero were intermediately biased FBGs. In fact, D tended to relate to sex-bias in gene expression by a wave-shaped pattern, which was significantly sigmoidal in three out of the four cases where the effect of SBG category was significant (third-order polynomial contrasts: California Dns: F1,4190 = 6.372, P = 0.012; California Ds: F1,4877 = 11.59, P < 0.001; Yemen Ds: F1,4851 = 8.45, P = 0.003). Fitted functions in e and f represent cubic polynomials. This pattern was also seen when instead modelling sex-bias as a continuous trait (Supplementary Fig. 4) and remained intact when accounting for variation in overall gene expression, gene length and GC content (Supplementary Table 5).

Variation in standing genetic variation within populations represents the outcome of several interacting processes, notably balancing selection, purifying selection and genetic drift. To estimate the net effect of these processes, we related Tajima’s D (D) to sexual dimorphism in expression. D summarizes the site-frequency spectrum (the distribution of single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP, frequencies in a population) and represents a measure of the relative proportion of variable sites at a given locus, normalized such that D = 0 is expected for genes under mutation-drift equilibrium while D > 0 signifies balancing selection and D < 0 purifying selection. Our analyses unveiled a characteristic wave-shaped relationship between expression dimorphism and D, which was consistent across populations and across synonymous and non-synonymous sites (Fig. 1e,f), showing that the strength and nature of overall selection depends upon the type and degree of sex-bias in gene expression. Weakly biased FBGs showed strongest signs of balancing selection within populations, consistent with an elevation of genetic variation in these genes due to SA selection. We identified 149 candidate SA loci, representing FBGs (log2FC > 1, where FC denotes fold change) that also showed Dns > 0 and Ds > 0 in all three populations. Classic theory23 predicts that the X chromosome should be enriched with SA loci24, and some population genomic studies have found support for this tenet25 while others have not26. We found little evidence for a general enrichment of candidate SA loci on the X chromosome in our study, as only two of these 149 loci were located on X-linked contigs (Fisher’s exact test; P = 0.336). We also note that genes with sex-limited expression, potentially reflecting genes where SA has been resolved1, were not significantly overrepresented on the X chromosome although this may in part reflect the apparent occurrence of partial dosage compensation and/or female X-inactivation in this species (Supplementary Results). Gene ontology enrichment analyses of our candidate set showed enrichment for genes involved in (1) a variety of general metabolic processes, (2) organelle (for example mitochondrial) organization and (3) cell division and egg production (Supplementary Table 6). Several of those FBGs that showed a signal of strong balancing selection in all three populations showed significant homologies with key metabolic genes, for example involved in ATP production, known to affect life-history traits such as life-span in other species27 (Supplementary Results).

Sexual conflict can be resolved by sex-limited expression of genes1. We therefore expect balancing SA selection to be absent or weakened in highly SBGs, as an indirect result of relaxed selection in the sex showing little or no expression of a given gene3. We found that overall balancing selection was indeed weakened in strongly FBGs (Fig. 1e,f). A similar finding in humans has been interpreted as evidence for SA selection being a major source of balancing selection among SBGs28. The fact that weakly SBGs showed the clearest hallmarks of balancing selection is consistent with the hypothesis that SA is more likely to promote the maintenance of polymorphism in genes where the evolution of sex-specific expression is constrained such that SA selection is more enduring29,30.

The pattern of overall selection in MBGs within populations was different from that in FBGs (Fig. 1e,f). While very weakly biased MBGs showed some evidence for overall balancing selection in two populations, intermediately biased MBGs tended to show, if anything, overall purifying selection. Clearly, the overall pattern of selection is distinct in MBGs and FBGs and the marked influence of balancing selection seen in intermediately biased FBGs was absent in MBGs. This does of course not negate the possibility that some MBGs may be involved in balancing SA selection but it does suggest that MBGs are overall more affected by negative selection than are FBGs. This is in concord with the suggestion that MBGs should be less constrained by pleiotropy than FBGs or unbiased genes4,8,30 and should be more affected by purifying sexual selection1 than FBGs. The fact that there are overall more MBGs than FBGs in C. maculatus supports this possibility as does the interesting fact that FBGs generally show more overlap across tissues than do MBGs19. Available evidence thus implies that FBGs are more often subject to antagonistic pleiotropy through shared function across sexes and tissues. We found further support for this hypothesis in that the degree of shared expression across tissues (abdomen versus head and thorax) among our 149 candidate SA loci was considerably and significantly higher (92%) than expected on the basis of all expressed genes (79%; Supplementary Results).

Several studies have shown that genetic variation in fitness in C. maculatus populations is, to an appreciable extent, SA16,17,18. Detailed phenotyping and experimental studies have placed general life-history traits, such as metabolic rate, locomotor activity, body mass, life-span, mitochondrial function and female egg production at the epicentre of SA selection13,14,15. The molecular hallmarks of selection documented here accord remarkably well with this previous body of research: general life-history genes tend to be female- rather than male-biased in expression in this species19 and we found that candidate SA loci were indeed enriched with genes involved in general metabolic processes and egg production. MBGs are instead enriched with genes with more special functions, such as receptor signalling pathways, visual perception, detection of chemical stimulus and neurotransmitter transport19. Interestingly, a focused analysis of 185 genes encoding C. maculatus male ejaculate proteins, which are male-biased in expression (Supplementary Results), under sexual selection12 and generally assumed to be candidate SA loci31, provided only limited evidence for overall balancing selection (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). Our results thus imply that genetic variation maintained by balancing SA selection is highly polygenic and is dominated by weakly FBGs involved in general life-history traits rather than by sex-specific traits under sexual selection in males.

Loci under balancing SA selection are predicted to show a higher degree of shared polymorphism across diverging populations, as ancestral polymorphisms are more likely to be maintained over time by balancing selection5. Previous studies have found that candidate SA loci are indeed more likely to show shared polymorphism, both across populations in fruit flies26 and across closely related species in flycatchers20. We tested this prediction by modelling the probability that genes carrying ≥1 SNP showed shared intermediate frequency polymorphism (minor allele frequency 0.3–0.5 in all three populations). This analysis revealed that FBGs showed a significantly higher probability of shared intermediate frequency polymorphism than did MBGs (Fig. 2). This is consistent with our analyses of balancing selection and, in fact, within-population estimates of D covaried strongly with shared polymorphism across populations (Supplementary Table 5). Genes with high values of Dns, and to a lesser extent also pN/pS, in the three populations were more likely to show shared polymorphism, while genes with more divergent estimates of Dns were less likely to show shared polymorphism. Male seminal fluid proteins and, in particular, sex-linked genes showed a relatively low incidence of shared intermediate frequency polymorphism, in concordance with a more pronounced role of purifying selection in these genes (Supplementary Fig. 7).

This figure shows predicted values (± s.e.m.) of the probability that a gene harbours ≥1 SNP that shows intermediate frequency polymorphism in all three populations across bins, from a generalized linear model (binomial errors and a logit link function) accounting for the effects of gene length and SNP density. The effect of SBG category on shared polymorphism, accounting for these covariates, was highly significant (Wald χ27 = 24.93, P < 0.001). Sample size per bin is n = 592–656 genes.

The identification of candidate SA loci can be refined by combining several metrics, each of which suggests a history of balancing SA selection6. We inspected the subset of genes showing (1) shared intermediate frequency polymorphism across populations, (2) signs of balancing selection within all populations (Dns > 1) and (3) at least weak sex-biased expression (log2FC > 1 or < −1). This identified 15 FBGs and 10 MBGs. Functional enrichment of these genes again showed an enrichment for general metabolic and catabolic processes (both sets) and egg production (the female set) (Supplementary Table 7).

We currently lack a recombination map of the C. maculatus genome and it is therefore not possible to assess whether and how variation in recombination rate across the genome might have influenced our results. C. maculatus has a fairly large (1.2 gigabases) and repeat-rich (>65%) genome with ten chromosome pairs (2n = 18 + XX/XY), and we found that genes carrying SNPs showing intermediate frequency polymorphism were distributed across contigs in accordance with random expectations rather than being enriched on some contigs (Supplementary Results). These facts suggest that linked selection is not responsible for the genome-wide patterns documented here.

Some studies have shown that loci with SB expression, in particular MB genes, tend to show increased rates of divergent sequence and expression evolution1. This is consistent with relaxed purifying selection in SBGs3 but is difficult to reconcile with theory4,7 and empirical observations26 of signals of balancing selection and shared polymorphism in candidate SA genes. This apparent incongruence is not yet fully resolved. Possible resolutions may include a release from SA constraints in strongly SBGs29, allowing such SBGs to respond to divergent sex-specific selection. Other factors may involve strong positive sexual selection in a subset of MB genes4, less constraints through antagonistic pleiotropy in certain MB genes1,4,30, the fixation of alternative alleles across some SA loci for complex polygenic traits under SA selection32 and the possibility that inter-locus SA coevolution2 spurs rapid evolution in a subset of SBGs. This is clearly an issue that deserves further attention.

In conclusion, the hypothesis that balancing SA selection has a major influence on genome-wide levels of genetic variation has considerable support from quantitative genetic studies but has rarely been tested using large-scale genomic data in species in which SA selection, SBG expression and SA phenotypes are well understood4. We provide such a test and our findings supported many key predictions and generated new insights ((1)–(4) as follows). (1) We found genome-wide evidence for relaxed purifying selection in SBGs, supporting the tenet that relaxed selection contributes to relatively high levels of genetic variation and rates of evolution of SBGs3. (2) However, our analyses also showed that indices of balancing selection showed a tighter covariation with shared genetic variation across populations than did those of relaxed purifying selection—the latter fact suggests that SA pleiotropy plays a central role in the elevation of genetic variation seen in SBGs. (3) Theory suggests that SA should be highly polygenic7, which seems to be true in Drosophila26. In line with this last prediction, our analyses identified many candidate SA loci. This molecular genetic finding corresponds well with recent quantitative genetic findings in this species, which have documented a negative genetic covariance between male and female reproductive fitness15,16,17 and have provided evidence for genome-wide sex-specific dominance reversal for fitness18. The latter phenomenon greatly increases the capacity for SA selection to generate balancing selection that results in stable polymorphism33 and promotes the maintenance of polygenic SA variation.

Finally, strong sexual selection on MBGs and male-specific traits has traditionally been assumed to be the primary generator of SA pleiotropy. In contrast to this belief, we found that (4) the footprints of balancing SA selection were most pronounced in weakly FBGs involved in metabolic processes that affect general life-history traits, matching previous studies identifying SA phenotypes in this species14,15,16,17,18. MBGs known to be under sexual selection in males (that is, male seminal fluid proteins) did not generally show consistent evidence for balancing SA selection. The degree to which the patterns documented here are general, as opposed to being specific for our model system, is currently unclear, as few studies have studied genetic diversity in SBGs in species with known SA phenotypes4,5. However, in conjunction with recent single-locus studies that have also revealed SA selection on genes related to metabolic processes and life-history traits33,34,35, our findings do suggest that our understanding of SA pleiotropy may need to be revised: a primary generator of this perpetual genetic tug-of-war between the sexes seems to be genes involved in a variety of general metabolic cascades, where sex-biased expression is constrained by shared function across the sexes.

Methods

Model system

The beetle C. maculatus (Bruchinae) is originally a West African species that has become a serious pest of legume crop seed stores in all tropical and subtropical arid regions of the world36. It has recently been established as an amenable model system in ecology and evolution because its natural habitat can be well replicated in the laboratory. Females lay eggs on dry beans and the larvae complete their development inside the bean in about 3 weeks under optimal conditions. This species shows an XY sex-determination system, with males being the heterogametic sex. We used the inbred South India SI4 reference strain for the genome assembly, to minimize SNP density in sequence data. We then resequenced three outbred populations, originally collected in Yemen, California and Brazil. Seed beetles were brought to Asia from West Africa by human farmers of its main host (Vigna unguiculata) some 2,000 years ago (Yemen) and were introduced to the Americas from West Africa by Spanish settlers in the early 1700s (California and Brazil)36. The three populations have been kept in the laboratory on V. unguiculata (29 °C, 65% relative humidity) for some 300 generations at population sizes >400 individuals. Refer to the Supplementary Materials and Methods for full details.

Genome assembly and annotation

A de novo genome assembly was generated using a sample (n = 12) of males from the SI4 strain. PacBio long-read sequences representing 32× genomic coverage with an average read-length of 9.0 kilobases were assembled using FALCON, and subsequently error-corrected based on realignment of both PacBio (32×) and Illumina (125×) reads. The resulting polished assembly is 1.01 gigabases in total size (somewhat smaller than the expected 1.19 gigabases genome size37), with an N50 of 149 kilobases and the longest contig spanning 2.1 megabases. Notably, RepeatMasker (v.4.0.5) identified as much as 64% of the assembly as repetitive elements (Supplementary Materials and Methods). Using a comprehensive MAKER3 pipeline using transcriptome data38, homology, and ab initio prediction methods, we identified 21,264 coding genes. Despite the high repeat content and the fragmented assembly, evaluations based on conserved proteins sets indicated a high fraction of well-assembled genes in the assembly (CEGMA: 85% complete, 11% partially complete; BUSCO: 75% complete, 10% partially complete). The CEGMA and BUSCO estimates for duplicated complete genes indicated a relatively high level of uncollapsed haplotypes in the assembly, not unusual for assemblies based on pooled samples (Supplementary Table 3).

Putative sex-linked contigs were identified by analysing Illumina read coverage, normalized to median coverage over all contigs, from Illumina sequencing of a male (~125×) and a female (~125×) sample from SI4 (HiSeq2000; two sequencing libraries and four lanes per sample). This is based on the prediction that X-linked contigs should show twice as high coverage in the female sample as in the male sample and that Y-linked contigs should have no or very low coverage in the female sample (see Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Resequencing

To assess polymorphism within and between populations, we sequenced pools of individuals (n = 100 males in each sample/pool) from Yemen, California and Brazil (two replicate samples per population)39. Each sample was sequenced in two Illumina lanes, resulting in ~62× coverage per sample (~125× per population).

Analyses

Data on gene expression were obtained from Immonen et al.19, who used RNA-seq of replicated samples of males and females to characterize expression. Here, we focused on all genes where data on sex-specific gene expression in the abdomen of adult reproductively mature virgin beetles were available (n = 4,993)19. These genes were grouped into eight bins, based on their pattern of SBG expression. Genes showing female-biased expression log2FC > 0; n = 2,623; FBGs) were divided into quartiles as were all genes showing male-biased expression (log2FC) < 0; n = 2,370; MBGs). Our inferences are based on (1) bootstrapped mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI; bias corrected) for each bin and/or (2) linear models treating bin as a fixed effect factor testing for effects of direction and relative magnitude of SB expression (Supplementary Results).

Parameters of interest were extracted from analyses in PoPoolation and PoPoolation2 (ref. 40), using default settings (Supplementary Materials and Methods). Genes harbouring ≥1 SNP showing a minor allele frequency of ≥0.3 in a given population were deemed to show intermediate frequency polymorphism in that population, given that genes showing minor allele frequencies of ≥0.3 show signs of balancing selection in Drosophila41. In these analyses, both samples from a given population were pooled.

We also analysed several additional gene sets. These were (1) a set of 741 enzymes involved in digestion of food in larval guts, (2) 185 male reproductive proteins42, (3) 126 candidate female reproductive proteins, (4) 281 candidate Y-linked genes and (5) 658 candidate X-linked genes. Refer to the Supplementary Results for the results for these gene sets.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The annotated genome assembly, along with sequence data, are available from the European Nucleotide Archive under accession PRJEB30475. Pool-seq raw sequencing data have been deposited at the NCBI sequence read archive, under the accession number PRJNA503561.

Code availability

Custom scripts have been published at GitHub where they are openly and freely available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3382061.

References

Parsch, J. & Ellegren, H. The evolutionary causes and consequences of sex-biased gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 83–87 (2013).

Arnqvist, G. & Rowe, L. Sexual Conflict (Princeton Univ. Press, 2005).

Dapper, A. L. & Wade, M. J. The evolution of sperm competition genes: the effect of mating system on levels of genetic variation within and between species. Evolution 70, 502–511 (2016).

Rowe, L., Chenoweth, S. F. & Agrawal, A. F. The genomics of sexual conflict. Am. Nat. 192, 274–286 (2018).

Kasimatis, K. R., Nelson, T. C. & Phillips, P. C. Genomic signatures of sexual conflict. J. Hered. 108, 780–790 (2017).

Mank, J. E. Population genetics of sexual conflict in the genomic era. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 721–730 (2017).

Connallon, T. & Clark, A. G. Balancing selection in species with separate sexes: insights from Fisher’s geometric model. Genetics 197, 991–1006 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Sturgill, D., Parisi, M., Kumar, S. & Oliver, B. Constraint and turnover in sex-biased gene expression in the genus Drosophila. Nature 450, 233–237 (2007).

Harrison, P. W. et al. Sexual selection drives evolution and rapid turnover of male gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4393–4398 (2015).

Wright, A. E. et al. Male biased gene expression resolves sexual conflict through the evolution of sex-specific genetic architecture. Evol. Lett. 2, 52–61 (2018).

Hotzy, C., Polak, M., Rönn, J. L. & Arnqvist, G. Phenotypic engineering unveils the function of genital morphology. Curr. Biol. 22, 2258–2261 (2012).

Goenaga, J., Yamane, T., Rönn, J. & Arnqvist, G. Within-species divergence in the seminal fluid proteome and its effect on male and female reproduction in a beetle. BMC Evol. Biol. 15, 266 (2015).

Berg, E. C. & Maklakov, A. A. Sexes suffer from suboptimal lifespan because of genetic conflict in a seed beetle. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 279, 4296–4302 (2012).

Berger, D., Berg, E. C., Widegren, V., Arnqvist, G. & Maklakov, A. A. Multivariate intralocus sexual conflict in seed beetles. Evolution 68, 3457–3469 (2014).

Berger, D. et al. Intralocus sexual conflict and the tragedy of the commons in seed beetles. Am. Nat. 188, E98–E112 (2016).

Berger, D. et al. Intralocus sexual conflict and environmental stress. Evolution 68, 2184–2196 (2014).

Bilde, T., Foged, A., Schilling, N. & Arnqvist, G. Postmating sexual selection favors males that sire offspring with low fitness. Science 324, 1705–1706 (2009).

Grieshop, K. & Arnqvist, G. Sex-specific dominance reversal of genetic variation for fitness. PLoS Biol. 16, e200681 (2018).

Immonen, E., Sayadi, A., Bayram, H. & Arnqvist, G. Mating changes sexually dimorphic gene expression in the seed beetle Callosobruchus maculatus. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 677–699 (2017).

Dutoit, L. et al. Sex‐biased gene expression, sexual antagonism and levels of genetic diversity in the collared flycatcher (Ficedula albicollis) genome. Mol. Ecol. 27, 3572–3581 (2018).

Kryazhimskiy, S. & Plotkin, J. B. The population genetics of dN/dS. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000304 (2008).

Gershoni, M. & Pietrokovski, S. Reduced selection and accumulation of deleterious mutations in genes exclusively expressed in men. Nat. Comm. 5, 4438 (2014).

Rice, W. R. Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution 38, 735–742 (1984).

Dean, R. & Mank, J. E. The role of sex chromosomes in sexual dimorphism: discordance between molecular and phenotypic data. J. Evol. Biol. 27, 1443–1453 (2014).

Lucotte, E. A. et al. Detection of allelic frequency differences between the sexes in humans: a signature of sexually antagonistic selection. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 1489–1500 (2016).

Ruzicka, F. et al. Genome-wide sexually antagonistic variants reveal longstanding constraints on sexual dimorphism in the fruitfly. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000244 (2019).

Berger, F., Ramı́rez-Hernández, M. H. & Ziegler, M. The new life of a centenarian: signalling functions of NAD(P). Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 111–118 (2004).

Cheng, C. & Kirkpatrick, M. Sex-specific selection and sex-biased gene expression in humans and flies. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006170 (2016).

Griffin, R. M., Dean, R., Grace, J. L., Rydén, P. & Friberg, U. The shared genome is a pervasive constraint on the evolution of sex-biased gene expression. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2168–2176 (2013).

Dean, R. & Mank, J. E. Tissue specificity and sex-specific regulatory variation permit the evolution of sex-biased gene expression. Am. Nat. 188, E74–E84 (2016).

Sirot, L. K., Wong, A., Chapman, T. & Wolfner, M. F. Sexual conflict and seminal fluid proteins: a dynamic landscape of sexual interactions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a017533 (2015).

Arnqvist, G., Vellnow, N. & Rowe, L. The effect of epistasis on sexually antagonistic genetic variation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 281, 20140489 (2014).

Barson, N. J. et al. Sex-dependent dominance at a single locus maintains variation in age at maturity in salmon. Nature 528, 405–408 (2015).

Lonn, E. et al. Balancing selection maintains polymorphisms at neurogenetic loci in field experiments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 3690–3695 (2017).

Rostant, W. G., Kay, C., Wedell, N. & Hosken, D. J. Sexual conflict maintains variation at an insecticide resistance locus. BMC Biol. 13, 34 (2015).

Kébé, K. et al. Global phylogeography of the insect pest Callosobruchus maculatus (Coleoptera: Bruchinae) relates to the history of its main host, Vigna unguiculata. J. Biogeo. 44, 2515–2526 (2017).

Arnqvist, G. et al. Genome size correlates with reproductive fitness in seed beetles. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 282, 20151421 (2015).

Sayadi, A., Immonen, E., Bayram, H. & Arnqvist, G. The de novo transcriptome and its functional annotation in the seed beetle Callosobruchus maculatus. PLoS ONE 11, e0158565 (2016).

Schlötterer, C., Tobler, R., Kofler, R. & Nolte, V. Sequencing pools of individuals—mining genome-wide polymorphism data without big funding. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 749–763 (2014).

Kofler, R. et al. PoPoolation: a toolbox for population genetic analysis of next generation sequencing data from pooled individuals. PLoS ONE 6, e15925 (2011).

Kelly, J. K. & Hughes, K. A. Pervasive linked selection and intermediate-frequency alleles are implicated in an evolve-and-resequencing experiment of Drosophila simulans. Genetics 211, 943–961 (2019).

Bayram, H., Sayadi, A., Immonen, E. & Arnqvist, G. Identification of novel ejaculate proteins in a seed beetle and division of labour across male accessory reproductive glands. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 104, 50–57 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to S. Chenoweth, L. Rowe and H. Ellegren for comments on a previous draft of the manuscript. Laboratory assistance was provided by J. L. Rönn and G. Engström. Sequencing was performed by the Uppsala University SNP&SEQ Technology Platform as part of the National Genomics Infrastructure at the Science for Life Laboratory, financially supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Bioinformatic work was supported by the National Bioinformatics Infrastructure Sweden, including the Wallenberg Advanced Bioinformatics Infrastructure. This work was financed by grants from the European Research Council (no. GENCON AdG-294333 to G.A.), the Swedish Research Council VR (no. 621-2014-4523 to G.A.) and FORMAS (no. 2018-00705 to G.A.). The computations were performed on resources provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) through Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.A., A.S. and B.N. conceived and designed this study. C.T.-R., A.S., B.N. and A.M.B. performed the genome assembly. J.D. annotated the genome. A.S., B.N., A.M.B., J.D. and E.I. conducted bioinformatic analyses. G.A., A.S. and A.M.B. analysed the data. G.A., A.S., B.N., D.B., A.M.B., J.D. and C.T.-R. provided intellectual input and drafted the first manuscript. G.A. revised and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material and Methods, Results, References, Tables 1–7 and Figs. 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sayadi, A., Martinez Barrio, A., Immonen, E. et al. The genomic footprint of sexual conflict. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 1725–1730 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1041-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-1041-9

This article is cited by

-

The genomics and evolution of inter-sexual mimicry and female-limited polymorphisms in damselflies

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

The roles of sexual selection and sexual conflict in shaping patterns of genome and transcriptome variation

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Correlation scan: identifying genomic regions that affect genetic correlations applied to fertility traits

BMC Genomics (2022)

-

Genomic evidence that a sexually selected trait captures genome-wide variation and facilitates the purging of genetic load

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022)

-

The draft genome of the specialist flea beetle Altica viridicyanea (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)

BMC Genomics (2021)