Abstract

Recombination between loci underlying mate choice and ecological traits is a major evolutionary force acting against speciation with gene flow. The evolution of linkage disequilibrium between such loci is therefore a fundamental step in the origin of species. Here, we show that this process can take place in the absence of physical linkage in hamlets—a group of closely related reef fishes from the wider Caribbean that differ essentially in colour pattern and are reproductively isolated through strong visually-based assortative mating. Using full-genome analysis, we identify four narrow genomic intervals that are consistently differentiated among sympatric species in a backdrop of extremely low genomic divergence. These four intervals include genes involved in pigmentation (sox10), axial patterning (hoxc13a), photoreceptor development (casz1) and visual sensitivity (SWS and LWS opsins) that develop islands of long-distance and inter-chromosomal linkage disequilibrium as species diverge. The relatively simple genomic architecture of species differences facilitates the evolution of linkage disequilibrium in the presence of gene flow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

How new species may arise and persist in the presence of gene flow is a fundamental and unresolved question in our understanding of the origins of biological diversity. This issue is particularly relevant in the ocean, where physical barriers are often poorly defined and pelagic larvae provide potential for extensive gene flow, but which nonetheless harbours some of the most diverse communities on Earth1. Indeed, diversity on coral reefs rivals the diversity seen in tropical forests2, and coral reef fish communities are among the most species-rich assemblages of vertebrates. The origin of coral reef fish families and functional groups dates back to the Palaeocene (66 million years ago); however, the vast majority of species arose within the past 5.3 Myr, with closely related species often differing primarily with respect to colour and patterning3.

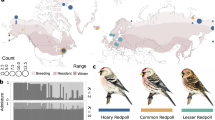

The hamlets (Hypoplectrus species; Serranidae)—a complex of 18 closely related reef fishes from the wider Caribbean (Fig. 1a)—provide an excellent context to explore speciation in the sea. Hamlets differ most notably in colour pattern, a trait that has been suggested to have direct ecological implications in terms of crypsis4,5 and mimicry4,6,7,8. Additionally, colour pattern plays a central role for reproductive isolation in this complex. Individuals mate assortatively with respect to colour pattern5,7,9,10 and it has been experimentally established that mate choice is driven by visual cues11. Nonetheless, spawnings between different species are observed at a low frequency (<2%) in natural populations5,7,9,10. Larvae from inter-specific crosses grow and develop normally12; those that have been raised past the juvenile stage show intermediate colour pattern phenotypes11, and individuals with intermediate phenotypes are also observed in natural populations at a low frequency13. Patterns of genetic divergence among species indicate that the radiation encompasses the entire range of genomic divergence (referred to as the speciation continuum14), from species that are nearly genetically indistinguishable7,9,10,15,16 to those that are well diverged17,18. There is extensive sympatry among hamlet species, with up to nine species co-occurring on Caribbean reefs10 with a high degree of overlap in feeding ecology and habitat19,20.

a, Three sympatric species from three locations. (B, Belize; H, Honduras; P, Panama) were targeted for resequencing. The area of sympatry among the three sampled species is highlighted in orange, and the distribution of the whole genus is shown in blue142. The three sampled species are the most common and widely distributed, but they represent just a fraction of the full hamlet diversity. Numbers indicate sample sizes. b, FST estimates among pairs of sympatric species, in order of increasing FST. Colours indicate the species pair, and labels on the x axis the location. c, PCA within each location, including genomic data from a total of 8,247,395 SNPs. PC, principal component.

Here, we focus on the lower end of the speciation continuum and examine patterns of genomic divergence among the three most abundant, widespread and genetically similar hamlets—the black hamlet (H. nigricans), barred hamlet (H. puella) and butter hamlet (H. unicolor) (Fig. 1a). We take advantage of their extensive and overlapping distributions to sample the three species in three reef systems in Panama, Honduras and Belize. This sampling design provides the opportunity to identify the genomic regions that are consistently differentiated among sympatric species across locations. Furthermore, microsatellite and restriction site-associated DNA (RAD) sequencing data from the same species and locations indicate that the levels of genetic differentiation among sympatric species are similar to the levels of differentiation among populations within species13,16,21, providing an opportunity to contrast between-species and between-population genetic architectures.

Given the slight genetic differences among species and the link between colour pattern, natural selection and mate choice, we made two predictions regarding genome-wide patterns of differentiation and divergence among the three species. First, we predicted that regions showing elevated and consistent differentiation between species would contain loci with strong functional links to either the development or the perception of colour pattern. Second, we reasoned that linkage disequilibrium (the non-random association of alleles at different loci) among these regions would develop as species diverge. Our second prediction derives from an influential theoretical paper by Felsenstein22, who identified recombination between loci underlying mate choice and ecological traits as a major evolutionary force acting against speciation with gene flow, with the corollary that the evolution of linkage disequilibrium between such loci is a fundamental step in the origin of species22. Empirical studies have shown that pleiotropy or physical linkage provide a direct way to generate associations between mate choice and ecology23,24,25, but it remains unclear whether and how long-distance linkage disequilibrium or inter-chromosomal linkage disequilibrium (ILD) between loci underlying mate choice and ecological traits may develop in the presence of gene flow14.

Results and discussion

Genome assembly and resequencing

To test these hypotheses, we assembled a reference genome for the hamlets. We used a combination of Illumina (245×) and PacBio (10×) data to assemble scaffolds, which were then anchored to a high-density linkage map including 24 linkage groups (denoted by ‘LG’ followed by a number)26, matching the 24 chromosomes expected in serranids27. The resulting assembly was 612 megabases (Mb) long with 92% of scaffolds anchored to the linkage map, resulting in a super-scaffold n50 of 24 Mb. We annotated 27,469 genes using a combination of ab initio gene predictions and RNA sequencing data from a variety of tissue types. Overall, there was broad synteny between the hamlet genome and the genome of the most closely related species with a similar high-quality genome—the three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Whole-genome analysis of 110 individuals (Fig. 1a) confirmed the striking genetic similarity among species and revealed differences in patterns of genetic differentiation (FST) among species in the three locations. Pairwise FST values among sympatric species ranged from 0.003 between H. puella and H. unicolor in Honduras to 0.035 between H. unicolor and H. nigricans in Panama (Fig. 1b). In all three locations, principal component analysis (PCA) clustered individuals by species; however, overall genetic differentiation among species showed differences among locations and was lowest in Honduras (FST among the three species = 0.004), intermediate in Belize (FST = 0.012) and highest in Panama (FST = 0.025) (Fig. 1c). PCA also suggested that some individuals might be of hybrid origin (for example, the two butter hamlets from Belize that clustered with barred hamlets). This hypothesis was corroborated by additional analyses based on Mendelian inheritance patterns of a small subset of highly differentiated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). A total of 8 high-probability hybrids or backcrosses were identified out of the 110 samples (5 in Belize, 2 in Honduras and 1 in Panama; Supplementary Fig. 2), establishing that gene flow is ongoing among species.

Similar to previous studies in other taxa28,29,30, differentiation was highly heterogeneous across the genome in local comparisons (Fig. 2), and a similar pattern was also evident when considering genotype × phenotype (G × P) associations (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, a large section of LG08 exhibited generally elevated levels of differentiation in all local comparisons. This may be explained by low levels of recombination along this linkage group (Supplementary Fig. 4), which might harbour a large chromosomal inversion. Nevertheless, patterns of differentiation in LG08 were not entirely consistent across locations or species, resulting in relatively weak differentiation in our global comparisons where samples were pooled across locations (Fig. 2, top panel).

The alternating white and grey blocks represent the 24 linkage groups. Each species pair is represented by one colour, pooled across locations (global) and within each location (Belize, Honduras and Panama). FST values correspond to the weighted mean per 50-kb window with 5-kb increments. Vertical bars on the right indicate the genome-wide weighted mean FST (note the different scale). The four genomic intervals above the 99.98th FST percentile in the global comparison are highlighted with a vertical line and labelled A–D.

Vision and pigmentation genes

In contrast with the pattern in LG08, four small (50–100-kilobase (kb)) genomic intervals were strongly and consistently differentiated among species, forming sharp ‘genomic islands’31 that stood out above the 99.98th percentile in the global comparisons considering either FST (Fig. 2) or G × P association (Supplementary Fig. 3). In agreement with our first hypothesis, each contained at least one candidate gene with a strong functional connection to either the development of colour pattern or sensory processes involved in pattern perception.

The sharp peak on LG09 (A in Fig. 2) contained sox10 (Fig. 3a). This gene encodes a transcription factor that has been shown to be involved in the development of melanophores in zebrafish32,33. The role of this gene in melanization is consistent with the finding of strong differentiation at this locus between the melanic species (H. nigricans) and the other two non-melanic species (H. puella and H. unicolor). Similarly, a strongly differentiated interval on LG12 (C in Fig. 2) was centred on the hoxca gene cluster (Fig. 3c). This region was identified in a previous genome scan using RAD sequencing16, but our new reference genome allowed us to localize the interval far more precisely. Hox genes code for homeodomain-containing transcription factors that play a central role in the patterning of tissues along the body axis, with 3′ genes expressed anteriorly and 5′ genes expressed posteriorly34. Hox genes can also be involved in the development of colour pattern phenotype. For example, they have been shown to play a role in the regulation of body pigmentation in birds35 and Drosophila36, as well as in eyespot formation on butterfly wings37. The strongest FST signal was positioned on hoxc13a specifically—the most 5′ gene of the hoxca cluster. This gene is known to be expressed in the caudal peduncle and at the pigment appearance stage in fishes38,39. Again, the specific role of this locus in patterning is consistent with pattern differences among hamlet species. This interval strongly differentiated H. unicolor, which has a prominent dark saddle on the caudal peduncle, from the other two species that lack this pattern. The possibility that hox genes may be involved in the development of colour pattern differences at a very shallow phylogenetic level in hamlets is intriguing and may provide an opportunity to better understand the links between micro- and macroevolutionary processes.

a–d, Linkage group, annotation, FST, dXY and genomic position for each of the four intervals above the 99.98th FST percentile (A–D, respectively, in Fig. 2). For clarity, only the genes in high FST regions are labelled, with candidate genes and non-synonymous SNPs within these genes highlighted in green. Coloured lines correspond to pairwise species comparisons (weighted mean; 10-kb window and 1-kb increments), and dots correspond to global FST values among the three species on a SNP basis. In all comparisons, species samples are pooled across the three locations.

The remaining two highly differentiated genomic intervals contained candidate loci with strong functional connections to vision. One of these two intervals was on LG12 (B in Fig. 2) and fell in an apparently non-genic region upstream of casz1 that strongly differentiated H. puella from the other two uniformly coloured species (Fig. 3b). The protein encoded by casz1 is a castor zinc finger transcription factor involved in a number of processes through development, including the development of photoreceptors40. Given that the visual system grows continuously in teleost fishes, we examined RNA expression in the retinas of 24 adult black, barred and butter hamlets from Panama. We confirmed that casz1 is consistently and strongly expressed in the retina, and also identified two splice variants of casz1 that extend the coding region across a large part of this peak (Fig. 3b). The other interval, on LG17 (D in Fig. 2), contained a cluster of short- and long-wave sensitive opsin genes (sws2aβ, sws2aα, sws2b and lws; Fig. 3d) that play a key role in the fine-tuning of visual sensitivity41. Unlike the previous intervals, which each differentiated a particular species from the other two, differentiation at this interval was not clearly species-specific. It was strongest in the comparison between the melanic (H. nigricans) and white (H. unicolor) species, where it presented a peak–valley–peak pattern that may reflect parallel adaptation from standing genetic variation42,43.

These four highly differentiated genomic intervals were narrow, and our highlighted candidate genes were not selectively picked from a large set of loci: the first peak on LG12 (B) contained only casz1; the second one (C) contained only hox genes (except for the calcoco1 locus) and was centred on hoxc13a specifically; and the peak on LG09 (A) contained only two genes, sox10 and rnaseh2a (Fig. 3). The last highly differentiated interval on LG17 (D) contained more genes, but the peak–valley–peak pattern was centred on the opsin genes specifically, with sws2b in the valley, and sws2aβ, sws2aα and lws in the two flanking peaks (Fig. 3). In line with ref. 44, simulations indicate that a combination of large effective population size (Ne = 10,000), intermediate migration rate (m = 0.01) and strong selection (s = 0.1–0.5) may generate sharp peaks of differentiation as observed in the hamlets (Supplementary Fig. 5).

It is noteworthy that all but one of the diverged SNPs in the four regions are either in non-coding regions or synonymous, suggesting that species differences are mainly driven by regulatory mechanisms. The only exception was one diverged, non-synonymous SNP on sws2aβ that corresponds to the bovine rhodopsin amino acid 200. Although not a known spectral tuning site, the location of this amino acid suggests that it might possibly be involved in spectral tuning41. We also note that only three genes (chac1_1, sema4b and cyp3a27) showed significant differences in expression among species in the retinal tissue (Supplementary Fig. 6), yet our methodology does not allow for the capture of differences in expression that may occur during development, in specific light environments (for example, at dusk at the time of spawning) or in specific cell types.

Additional vision and pigmentation genes were identified by extending our analyses to the genomic regions above the 99.90th FST percentile that presented weaker or less consistent differentiation among species. This less stringent selection identified 14 additional intervals across 7 linkage groups (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8 and Supplementary Table 1), 4 of which contained further vision or pigmentation genes (Supplementary. Fig. 9). ednrb on LG04 (E in Supplementary Fig. 7) is involved in zebrafish melanophore and iridophore development45 and again differentiated H. nigricans from the other non-melanic species. One interval on LG08 (F in Supplementary Fig. 7) presented a non-species-specific peak–valley–peak pattern centred on foxd3, which encodes a transcription factor also involved in melanophore differentiation in zebrafish46. A further interval on LG08 (G in Supplementary Fig. 7) included rorb, which plays a critical role during photoreceptor differentiation in mice47. Similar to casz1 (the other gene involved in photoreceptor development), rorb singled out H. puella and was consistently and strongly expressed in the retina (Supplementary Fig. 6). Finally, invs on LG20 (H in Supplementary Fig. 7) is involved in the transport of opsins into the outer segment of photoreceptors48.

Long-distance linkage disequilibrium and barrier genes

The four intervals that showed marked differentiation in our genome-wide comparison were either on different linkage groups or 2 Mb apart on the same linkage group (B and C), which is well beyond physical linkage in hamlets (Supplementary Fig. 10d). The four candidate intervals are therefore not physically linked. Nevertheless, in line with our second hypothesis, these intervals showed islands of elevated long-distance linkage disequilibrium and ILD in a backdrop of nearly zero genome-wide ILD (Fig. 4a,b). In addition, there was a build-up of ILD with increasing genome-wide differentiation, with the weakest ILD in Honduras, intermediate in Belize and most pronounced in Panama (Fig. 4c,d). As expected, there was no ILD among these intervals within species (Fig. 4e). The same patterns were observed when considering the four additional vision and pigmentation genes above the 99.90th FST percentile (Supplementary Fig. 11).

a, The four intervals displayed islands of increased linkage disequilibrium. b, Genome-wide ILD. Box edges represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers show 1.5× the interquartile range, dots are outliers, and red lines represent the r2 expectation for the mean (1/2n, where n is the sample size). Genome-wide ILD was lower for the global dataset due to the larger sample size (n = 110) compared with the location- and species-specific datasets (n = 35–39). c, ILD among the four candidate intervals. d, Linkage disequilibrium among the four intervals increased with increasing differentiation among species (grey gradient). e, In contrast, linkage disequilibrium among the four intervals was low or absent within species. r2 values are shown on a SNP basis in b and c and averaged over two-dimensional bins of 10 × 10 kb in a,d and e.

Local regions of strong differentiation can arise for a number of reasons49,50, including processes unrelated to speciation such as background selection51 or the sorting of ancestral polymorphisms52. These processes are almost certainly operating within hamlet species. Indeed, we see an expected build-up of genetic differentiation across a large region on LG08 with very low recombination. This region may be a large chromosomal inversion and is exceptional as it contains 6 of the 14 intervals that showed moderate levels of differentiation among species. Nonetheless, the sharp erosion in overall levels of differentiation among species in our global comparisons, coupled with the elevated differentiation among populations of the same species (Supplementary Fig. 12), suggests that this region does not contain loci that are essential for the maintenance of species differences and that, if it does contain an inversion, it is polymorphic both within and between species.

In contrast, there are a number of compelling reasons to argue that the four intervals that showed much stronger and consistent differentiation among species contain the loci responsible for reproductive isolation. Foremost, all of them contain genes involved in vision, pigmentation or patterning in vertebrates, fitting our initial expectations about the types of loci involved in speciation based on the ecology and reproductive biology of these species. This pattern is even more compelling when considering that variation at the candidate loci for pigmentation (sox10) and patterning (hoxc13a) parallels the specific colour pattern differences that characterize hamlets (melanization and marking on the caudal peduncle). Moreover, our sampling design permits us to isolate genomic intervals that are consistently differentiated among species across locations, effectively filtering out processes acting within populations, and to establish that differentiation is specific to between-species comparisons. In contrast with the low-recombining region on LG08, differentiation in the four intervals was weaker or absent when comparing populations within species (Supplementary Fig. 12). Furthermore, the effects of background selection are unlikely to be important in the earliest stages of differentiation studied here53. This is confirmed by the weak genome-wide correlation between recombination rate and differentiation, and by the fact that our four candidate intervals do not show particularly low recombination rates (Supplementary Fig. 10). Finally, patterns of differentiation (FST) across these intervals were paralleled by genetic divergence (dXY; Fig. 3). This is the expected genomic signature of so-called barrier genes54 that maintain species differences in the face of gene flow55.

Linkage disequilibrium, gene flow and speciation in the sea

In the presence of gene flow, the extent of selection that is required to maintain long-distance linkage disequilibrium or ILD increases with the number of loci involved56. This is because the number of possible genotypes in backcrosses increases exponentially with the number of loci57. Thus, disproportionally stronger selection is required to filter species-specific genotypes as the number of loci increases55. In hamlets, a small number of genomic intervals are strongly and consistently differentiated among species. This simple genetic architecture is expected to facilitate the build-up of ILD. Furthermore, differentiation is species specific at three of these genomic intervals. Accordingly, long-distance linkage disequilibrium and ILD are not systematically observed among all pairs of intervals in all species pairs (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Once gene flow is sufficiently reduced through strong assortative mating, divergence and linkage disequilibrium can accumulate rapidly by a combination of extrinsic and intrinsic forces56. This is exactly the pattern we capture within the three hamlet species, which show a gradient of increasing differentiation and linkage disequilibrium among populations (Figs. 1b,c and 4c,d and Supplementary Fig 11b). The build-up of more pervasive ILD might be aided by epistatic interactions among loci. For example, foxd3 on LG08 and sox10 on LG09 both regulate the expression of mitf, a transcription factor involved in the development of melanophores in zebrafish33,46. ednrb on LG04 (ref. 45) is also involved in the development of melanophores in zebrafish, and these three intervals show strong ILD when compared between the melanic (H. nigricans) and white (H. unicolor) species (Supplementary. Fig. 14).

Our data provide a compelling scenario where speciation is driven by a combination of assortative mating and natural selection acting on a small number of large-effect loci, among which long-distance linkage disequilibrium and ILD are maintained in the presence of gene flow. The relatively simple genomic architecture underlying species differences in hamlets parallels that observed in parapatric bird subspecies29, parapatric butterflies races30 and depth-segregated cichlid ecomorphs28, and we suggest that such a simple genomic architecture may be an important initial condition for the origin of many new species. Hamlets stand out from these other case studies by being fully sympatric at both the macro (overlapping distributions) and micro (overlapping habitats) geographic scales. In this respect, they provide a counter-example to the idea that divergence tends to be genomically widespread among species that are fully sympatric14. The relatively simple genomic architecture observed in hamlets also contrasts with other systems in which differentiation is more widespread across the genome58,59,60. Factors contributing to this difference may include recent divergence, relatively high levels of gene flow associated with extensive sympatry, and a simple genetic basis of the traits involved in reproductive isolation in hamlets. In addition, the two-week planktonic larval stage of hamlets provides potential for long-distance dispersal11. Nonetheless, our genomic data show that local evolutionary processes are operating in three communities separated by only a few hundred kilometres, despite this dispersal phase. For example, H. puella and H. unicolor present two marked peaks of differentiation on LG17 in Panama that are not observed in Belize and Honduras for the same species pair. Marine speciation can therefore be characterized by local, heterogeneous and complex processes, as observed in terrestrial and freshwater systems notwithstanding the apparent homogeneity of the marine environment.

Methods

Sampling

The majority of samples considered in this study were already available from previous studies7,10. New samples were only collected in Bocas del Toro (Panama) for RNA expression analysis (following methods published previously61 and relevant ethical regulations under Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol 2017-0101-2020-2 and Panamanian Ministry of Environment permits SC/A-53-16 and SEX/A-35-17). Samples for expression analysis were collected in the early afternoon, kept in tanks overnight under natural light conditions and processed at noon on the following day. Only samples that could be unambiguously assigned to species on the basis of their colour pattern were considered.

Software versions, parameter settings and scripts

Software versions and parameter settings were omitted from the text for readability. Software versions are instead listed in Supplementary Table 2. All software parameter settings and scripts needed to reproduce our results, from raw data to figures, are provided in the accompanying repository (https://doi.org/10.3289/SW_2_2018; hereafter, git).

De novo genome assembly

Library preparation and sequencing

Genome assembly was based on a single barred hamlet (H. puella) from Panama (ID: 27678; Supplementary Table 3). Genomic DNA was extracted from gill and muscle tissue using Qiagen MagAttract kits. Four paired-end 2 × 151-base pair (bp) libraries with insert sizes ranging from roughly 250 to 320 bp were prepared, as well as one paired-end 2 × 251-bp PCR-free library with a 580-bp insert size (Supplementary Table 4). Furthermore, two mate-pair libraries with insert sizes of about 2.5 and 4.3 kb were prepared. All paired-end and mate-pair libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2000/2500 platforms. Finally, Illumina data were complemented with longer PacBio reads from 20 single molecule, real-time (SMRT) sequencing cells. All sequencing for genome assembly was done at the Duke Center for Genomic and Computational Biology.

For annotation, RNA was extracted from gill, liver and muscle tissue from a single individual (ID: 16_2130; Supplementary Table 3) with an Invitrogen PureLink mRNA Mini Kit and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq at the STRI in Panama. Additionally, RNA was extracted from the retinal tissue of 24 hamlets from Bocas del Toro, Panama (Supplementary Table 5), and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform by Novogene.

Illumina sequencing data preparation

Before assembly, the sequencing data were preprocessed to remove low-quality reads and possible contamination. As a first step, Illumina adaptors and low-quality reads were trimmed or filtered using Trimmomatic62 (paired-end and mate-pair libraries; git 1.1.1.1) and NextClip63 (mate-pair libraries; git 1.1.1.2 and 1.1.1.3).

To check for contamination, the filtered data were screened for bacterial and viral content using Kraken64 (default database and settings; git 1.1.1.4 and 1.1.1.5), and classified reads were discarded using seqtk (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk; git 1.1.1.6). To remove possible human contamination, a two-step approach was applied. First, the reads were mapped against the human genome (GRCh38.p5) using Bowtie2 (ref. 65) and hits were removed from the sample (git 1.1.1.7). The discarded reads were then mapped against the genome of the Asian seabass Lates calcarifer66 (git 1.1.1.8). The aim was to identify reads from conserved regions shared between the hamlet and the human genome. These reads were then merged back into the original samples (git 1.1.1.9).

PacBio sequencing data preparation

Preparation of the PacBio data was done with proovread67 and Trimmomatic (git 1.1.2.0−1.1.2.5). The first 25 bp of all reads were trimmed to remove PacBio adaptors. Then, a subset (∼40×) of the filtered 2 × 251-bp PCR-free Illumina library (number 5 in Supplementary Table 4) was mapped against the PacBio data. The mapping results were used to correct the PacBio reads and break apart chimeric reads. The whole process was parallelized using the SeqChunker script distributed with proovread. The results of every step were monitored with FastQC68 and MultiQC69 throughout the preparation phase.

De novo genome assembly

After exploring a number of assemblers, Platanus70 was chosen due to its good performance with the relatively heterozygous hamlet genome, using only the Illumina data in a first step. The contiging was based on the paired-end libraries, and both paired-end and mate-pair libraries were used for scaffolding and gap closing (git 1.2.1−1.2.3). The resulting scaffolds were additionally gap closed with the Illumina-corrected PacBio data using PBjelly71 (git 1.2.4.1−1.2.4.6). Finally, the twofold gap-closed scaffolds were anchored and oriented to two RAD-based hamlet linkage maps26 using Allmaps72. Briefly, the linkage map RAD tags were mapped onto the assembly scaffolds using Bowtie2 and the physical positions of the markers on the scaffolds were retrieved. Using custom R73 scripts, the physical positions (bp) from the mapping were combined with the linkage map positions (cM) (git 1.2.5). The resulting maps were merged into a single file and used for anchoring with Allmaps (git 1.2.6).

Manual curation

The anchored assembly was unmasked to capitalize lower-case sections resulting from PBjelly. The mitochondrial scaffold was identified by mapping the mitochondrial genome of the blue hamlet (Hypoplectrus gemma; GenBank accession number: FJ848375) to the assembly. Finally, scaffolds smaller than 500 bp were removed from the assembly using SAMtools74 and bedtools75 (git 1.2.7). At this point, the assembly was considered complete and used as a reference throughout the study (hereafter, the hamlet reference genome).

Quality assessment

The final assembly was aligned with the stickleback genome76 (G. aculeatus; https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.846nj)—the most closely related high-quality genome—using LAST77 (git 1.2.8). The alignments were visualized using Circos78 based on matches larger than 5 kb (git 2.2.0.1). The large-scale synteny among the two genomes (Supplementary Fig. 1) was interpreted as a validation of the general structure of the hamlet genome assembly, and the hamlet linkage groups were numbered following the numbering of the homologous stickleback linkage groups. Furthermore, the presence of genes highly conserved in vertebrates was assessed using BUSCO79, and summary statistics for the assembly were generated with the summarizeAssembly.py script provided in the PBjelly suite.

Recombination landscape

To assess the large-scale recombination landscape, the RAD tags from the linkage map were mapped with Bowtie2 to the final assembly (git 1.2.9). A rough estimate of the recombination density was provided by dividing linkage (cM) by physical distances (Mb) using R.

Annotation

The RNA libraries were assembled into a combined transcriptome as a basis for genome annotation. To prepare the reference genome, it was screened for specific repeat families using RepeatModler80 (git 1.3.1), and repeats were masked for mapping using RepeatMasker81 (git 1.3.2). Scaffolds that contained only masked sequences were removed from the assembly. The RNA sequences were quality checked using FastQC, quality filtered using Trimmomatic (git 1.3.3) and mapped onto the masked version of the reference genome using HISAT2 (git 1.3.4)82. The transcriptome was assembled from the mapped sequences using Trinity83 in genome_guided mode (git 1.3.5). Preliminary gene models were constructed using the MAKER package84, combining the information from de novo assembled transcripts with evidence-based, full-length protein sequences from zebrafish and stickleback (UniProt85). Functional inferences were generated using similarity searches of the annotated gene models against UniProt/Swiss-Prot and InterProScan86, followed by manual curation of selected genes of interest with the WebApollo platform87.

Resequencing and variant calling

Resequencing

The black (H. nigricans), barred (H. puella) and butter (H. unicolor) hamlets from Panama, Honduras and Belize were considered for resequencing. A total of 11–13 individuals were sequenced per species and location, adding up to a total of 110 samples (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 3). An additional golden hamlet (H. gumigutta) was genotyped but excluded before analysis. Genomic libraries were prepared at the STRI in Panama (Belize and Honduras samples) and Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology in Kiel, Germany (Panama samples) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 (paired end, 2 × 151) by Novogene (Belize and Honduras samples) and the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology in Kiel (Panama samples) at a mean sequencing depth of 24× (Supplementary Table 3).

Variant calling

The genotyping procedure followed the best practice recommendations for the GATK88 work flow provided by the Broad Institute89,90. We describe here the general work flow, while the exact parameters used for each step are specified in git 2.1.1−2.1.12. Note that the samples from Panama were sequenced first and prepared independently of the Belize and Honduras samples, but processed together from the variant calling stage onwards (git 2.1.7).

Picard Tools91 was used to transform the sequences from fq to uBAM format, assign read groups, mark adaptors and back-transform into fq format (git 2.1.1−2.1.3). They were then mapped to the hamlet reference genome using BWA74 and merged with the uBAM files containing the read group information with Picard Tools (git 2.1.3). Afterwards, duplicated reads were removed (git 2.1.4). Then, using GATK, genotype likelihoods were called (git 2.1.6) and all 110 samples were genotyped jointly (git 2.1.7.1). This step was duplicated, generating one dataset with variant sites only (git 2.1.7.1.call_variants.sh) to be used for phasing and another dataset including every callable site (even invariant ones; git 2.1.7.all_Variants_temp.sh) to calculate π and dXY. SNPs were extracted from the raw genotypes and hard filtered with respect to quality (git 2.1.8). Furthermore, SNPs with missing data in more than 11 genotypes, as well as multiallelic SNPs, were removed using VCFtools92 (git 2.1.8).

For the ‘all callable sites’ dataset, the genotypes (VCF) were subset by linkage group (git 2.1.9) and transformed to a custom genotype format required for popgenWindows.py93 (git 2.1.10.vcf_2_geno_temp.sh).

The SNPs-only dataset was subset by linkage group as well (git 2.1.9.subset_LGs.sh). Phase-informative reads were extracted (git 2.1.10.loop_extractPIRs.sh) and the genotypes were phased (git 2.1.11) using SHAPEIT94. As a final step, SNPs with a minor allele count of 1 (minor allele frequency < 0.9%) were removed from the dataset (git 2.1.12).

Population genomics

Most population genomic statistics were calculated within sliding windows along the genome. This was done at two resolutions. For a genome-wide overview, a window size of 50 kb with 5-kb increments was chosen. For more fine-scale analysis, a window size of 10 kb with 1-kb increments was applied. In the following, these two resolutions are referred to as broad and fine scale.

PCA

For the PCA, the SNPs-only dataset was subset by location using VCFtools, and the subsets were reformatted. The three PCAs were then run independently using the R package pcadapt95 (git 2.2.4). Similar results were obtained when considering physically unlinked SNPs only (Supplementary Fig. 15).

π

Nucleotide diversity was based on the ‘all callable sites’ dataset and computed with VCFtools. It was calculated for each species, as well as each species pair within each population at fine-scale resolution (git 2.2.2 and 2.2.3).

d XY

Genetic divergence96 was based on the reformatted ‘all callable sites’ dataset. It was calculated for each population pair within each location in both resolutions using popgenWindows.py93 (git 2.2.1).

F ST

Genetic differentiation97 was based on the SNPs-only dataset and computed with VCFtools, using the weighted mean following Weir and Cockerham97. It was calculated at both resolutions for each species pair, both within each location and globally, as well as on a SNP basis among the three species pooled over locations. Additionally, it was calculated in broad resolution for every pair of locations within each species and globally (git 2.2.5).

G × P

G × P associations were based on the SNPs-only dataset and estimated using a linear model (-lm) with GEMMA98. For this, the dataset was transformed to the PLINK format using VCFtools and PLINK99. G × P association was calculated on a SNP basis for every species pair, both within each location and globally, as well as for every pair of locations both within each species and globally (git 2.2.6.2 and 2.2.6.3). The results were then averaged over windows at both resolutions for the species comparisons, and at broad resolution for the location comparisons using custom shell scripts (git 2.2.6.4−2.2.6.6). Note that Wald-test P values were −log10 transformed before averaging, so that \({\overline{-{{\rm{log}}_{10}}(P)}}\) was reported for every window. GEMMA was additionally run under the linear mixed model, which provided similar results (Supplementary Fig. 16). Note also that the G × P association, when applied to discrete phenotypes as done here, introduces some degree of redundancy with respect to FST.

r 2

Linkage disequilibrium(r2) was calculated using VCFtools (git 2.2.8.1) at four different levels. First, to estimate the decay of linkage disequilibrium with physical distance, the pairwise r2 for all SNPs within 20 randomly selected windows of 15 kb was calculated. Second, to establish a baseline, genome-wide levels of linkage disequilibrium were estimated from a random subset of 570 SNPs separated by at least 1 Mb (to rule out physical linkage) and considering inter-chromosomal pairs of SNPs only (ILD). Third, r2 was calculated for all SNPs in and between broad regions around the candidate intervals. Fourth, considering only SNPs within the candidate intervals (exact regions: git LD.bed and extendedLD.bed). The SNPs within the regions considered were then collated to allow continuous visualization (git 2.2.8.2 and 2.2.9.2). The pairwise r2 values were sorted into two-dimensional bins of 10 × 10 kb each, and the average r2 value for each bin was then calculated using R (git 2.2.8.3 and 2.2.9.3). Note that r2 = 0 when there is no linkage, as opposed to the recombination rate r (not considered here), which equals 0.5 in the absence of linkage.

Hybrids and backcrosses

The approach implemented in NewHybrids100 was used to test our hypothesis that some individuals might be of hybrid origin. This method does not require the a priori identification of pure individuals and relies on an explicit genetic model based on Mendelian inheritance. These analyses were run on small subsets of the SNPs-only dataset. First, for every pairwise species comparison within each location, the 800 SNPs with highest FST values were selected. These SNP subsets were further filtered to include only SNPs that are separated by at least 5 kb, to limit the effect of physical linkage among SNPs. From the resulting SNPs, 80 were randomly chosen to ensure that all analyses are based on the same number of markers. Note that the results were robust to alternative SNP selection strategies. Subsetting was done using a combination of R, VCFtools and unix commands (git 2.2.10.1 and 2.2.10.2). The SNP subsets were transformed to the NewHybrids input format using PGDSpider101 (git 2.2.10.2). NewHybrids100 was run in parallel using the R package parallelnewhybrid102 with a burn-in of 106 iterations and 10 × 106 sweeps (git 2.2.10.3).

ρ

The population recombination rate was estimated using the machine learning R package FastEPRR103. It was based on the SNPs-only dataset and calculated within non-overlapping windows of 50 kb using 250 parallel jobs (git 2.2.11.1–2.2.11.3). For visualization, the results where reformatted using a custom bash script (git 2.2.11.4).

RNA expression

A FASTA version of the transcriptome was created from the genome annotation file (GFF in combination with the hamlet reference genome using gffread104 (git 2.3.1). The reference transcriptome was then indexed (git 2.3.2) and transcript abundances of the filtered retina RNA samples (also used for annotation) were estimated using kallisto105 (git 2.3.3). Expression was analysed using the R package DSeq2 (git 3_figures and docs/index.html)106.

Simulations

Simulations were conducted to explore which combination of parameters may generate patterns of differentiation as sharp as the ones observed in the four candidate regions. Several demographic scenarios were simulated using the coalescent simulator msms107, considering a selected site located in the middle of a 500-kb chromosome. The simulations consisted of two populations of constant size Ne that split t generations ago and experienced constant and symmetrical migration (m) since then. The selected site was a single codominant locus with two alleles, A and a, that are advantageous in populations 1 and 2, respectively, with a fitness of 1 + s for homozygotes and 1 + s/2 for heterozygotes, where s is the selection coefficient. We explored the parameter space spanned by the combinations of Ne ∊ {1,000, 10,000, 100,000}, t ∊ {10,000, 100,000, 1,000,000}, m ∊ {0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.10} and s ∊ {0.05, 0.1, 0.5}. The simulations were conducted with a recombination rate r of 0.02, providing a population recombination rate 4Ner similar to the one estimated from the empirical data with FastEPRR.

Sequences were simulated on the basis of the simulated genealogies using Seq-Gen108, and variable sites were exported to the VCF format using msa2vcf109. The VCF files were then used to calculate FST with VCFtools over 10-kb windows with 1-kb increments. NextFlow110 was used to manage the simulations and analysis across the entire parameter space. Visualization of the results was done within R (git 3_figures and docs/index.html).

Visualization

All of the results were plotted using R, with the exception of the synteny plot (Supplementary Fig. 1, Circos) and LG08 low-recombination plot (Supplementary Fig. 4, Allmaps and Inkscape). Details of the visualization are provided in the R scripts and their documentation (git 3_figures and docs/index.html). Within those R scripts, the following packages were used: bookdown (0.7)143,111, colorspace (1.3–2)112, cowplot (0.9.2)113, DESeq2 (1.16.1)106, dplyr (0.7.4)114, FastEPRR (1.0)103, gdata (2.18.0)115, ggforce (0.1.2)116, ggmap (2.6.1)117, ggplot2 (3.0.0)118, ggrepel (0.7.0)119, gplots (3.0.1)120, grConvert (0.1–0)121, grid (3.4.3)73, gridExtra (2.3)122, gridSVG (1.60)123, grImport2 (0.1–4)124, gtable (0.2.0)125, hrbrthemes (0.1.0)126, knitr (1.20)127,128,129, maptools (0.92)130, marmap (0.9.6)131, parallelnewhybrid (0.0.0.9002)102, PBSmapping (2.70.4)132, pcadapt (3.0.4)95, RColorBrewer (1.1–2)133, rtracklayer (1.36.6)134, scales (0.5.0.9000)135, scatterpie (0.0.9)136, sp (1.27)137,138, tidyverse (1.2.1)139, tximport (1.4.0)140 and vsn (3.44.0)141.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data and genome assembly (FASTA format) are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (project accession number PRJEB27858). Accession numbers for all of the sample sequences are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 5. Additional data underlying this study, including the genome annotation (GFF format), genotypes (VCF format), and per-locus FST and G × P results, are deposited in Dryad (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pg8q56g).

References

Palumbi, S. R. Genetic divergence, reproductive isolation, and marine speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 25, 547–572 (1994).

Reaka-Kudla, M. L. in Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting our Biological Resources Vol. 2 (eds Reaka-Kudla, M. L., Wilson, D. E. & Wilson, E. O.) 83–108 (Joseph Henry Press, Washington DC, 1997).

Bellwood, D. R., Goatley, C. H. & Bellwood, O. The evolution of fishes and corals on reefs: form, function and interdependence. Biol. Rev. 92, 878–901 (2017).

Thresher, R. E. Polymorphism, mimicry, and the evolution of the hamlets (Hypoplectrus, Serranidae). Bull. Mar. Sci. 28, 345–353 (1978).

Fischer, E. A. The relationship between mating system and simultaneous hermaphroditism in the coral-reef fish, Hypoplectrus nigricans (Serranidae). Anim. Behav. 28, 620–633 (1980).

Randall, J. E. & Randall, H. A. Examples of mimicry and protective resemblance in tropical marine fishes. Bull. Mar. Sci. 10, 444–480 (1960).

Puebla, O., Bermingham, E., Guichard, F. & Whiteman, E. Colour pattern as a single trait driving speciation in Hypoplectrus coral reef fishes?. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 1265–1271 (2007).

Puebla, O., Picq, S., Lesser, J. S. & Moran, B. Social-trap or mimicry? An empirical evaluation of the Hypoplectrus unicolor–Chaetodon capistratus association in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Coral Reefs 37, 1127–1137 (2018).

Barreto, F. S. & McCartney, M. A. Extraordinary AFLP fingerprint similarity despite strong assortative mating between reef fish color morphospecies. Evolution 62, 226–233 (2008).

Puebla, O., Bermingham, E. & Guichard, F. Pairing dynamics and the origin of species. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 1085–1092 (2012).

Domeier, M. L. Speciation in the serranid fish Hypoplectrus. Bull. Mar. Sci. 54, 103–141 (1994).

Whiteman, E. A. & Gage, M. J. G. No barriers to fertilization between sympatric colour morphs in the marine species flock Hypoplectrus (Serranidae). J. Zool. 272, 305–310 (2007).

Puebla, O., Bermingham, E. & Guichard, F. Population genetic analyses of Hypoplectrus coral reef fishes provide evidence that local processes are operating during the early stages of marine adaptive radiations. Mol. Ecol. 17, 1405–1415 (2008).

Seehausen, O. et al. Genomics and the origin of species. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 176–192 (2014).

McCartney, M. A. et al. Genetic mosaic in a marine species flock. Mol. Ecol. 12, 2963–2973 (2003).

Puebla, O., Bermingham, E. & McMillan, W. O. Genomic atolls of differentiation in coral reef fishes (Hypoplectrus spp., Serranidae). Mol. Ecol. 23, 5291–5303 (2014).

Victor, B. C. Hypoplectrus floridae n. sp. and Hypoplectrus ecosur n. sp., two new barred hamlets from the Gulf of Mexico (Pisces: Serranidae): more than 3% different in COI mtDNA sequence from the Caribbean Hypoplectrus species flock. J. Ocean Science Found. 5, 2–19 (2012).

Tavera, J. & Acero, A. P. Description of a new species of Hypoplectrus (Perciformes: Serranidae) from the Southern Gulf of Mexico. Aqua 19, 29–38 (2013).

Whiteman, E. A., Côté, I. M. & Reynolds, J. D. Ecological differences between hamlet (Hypoplectrus: Serranidae) colour morphs: between-morph variation in diet. J. Fish Biol. 71, 235–244 (2007).

Holt, B. G., Emerson, B. C., Newton, J., Gage, M. J. G. & Cote, I. M. Stable isotope analysis of the Hypoplectrus species complex reveals no evidence for dietary niche divergence. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 357, 283–289 (2008).

Picq, S., McMillan, W. O. & Puebla, O. Population genomics of local adaptation versus speciation in coral reef fishes (Hypoplectrus spp, Serranidae). Ecol. Evol. 6, 2109–2124 (2016).

Felsenstein, J. Skepticism towards Santa Rosalia, or why are there so few kinds of animals. Evolution 35, 124–138 (1981).

Hawthorne, D. J. & Via, S. Genetic linkage of ecological specialization and reproductive isolation in pea aphids. Nature 412, 904–907 (2001).

Kronforst, M. R. et al. Linkage of butterfly mate preference and wing color preference cue at the genomic location of wingless. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6575–6580 (2006).

Bay, R. A. et al. Genetic coupling of female mate choice with polygenic ecological divergence facilitates stickleback speciation. Curr. Biol. 27, 3344–3349 (2017).

Theodosiou, L., McMillan, W. O. & Puebla, O. Recombination in the eggs and sperm in a simultaneously hermaphroditic vertebrate. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20161821 (2016).

Arai, R. Fish Karyotypes: A Check List (Springer, Tokyo, 2011).

Malinsky, M. et al. Genomic islands of speciation separate cichlid ecomorphs in an East African crater lake. Science 350, 1493–1498 (2015).

Vijay, N. et al. Evolution of heterogeneous genome differentiation across multiple contact zones in a crow species complex. Nat. Commun. 7, 13195 (2018).

Van Belleghem, S. M. et al. Complex modular architecture around a simple toolkit of wing pattern genes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 52 (2017).

Turner, T. L., Hahn, M. W. & Nuzhdin, S. V. Genomic islands of speciation in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Biol. 3, e285 (2005).

Dutton, K. A. et al. Zebrafish colourless encodes sox10 and specifies non-ectomesenchymal neural crest fates. Development 128, 4113–4125 (2001).

Elworthy, S., Lister, J. A., Carney, T. J., Raible, D. W. & Kelsh, R. N. Transcriptional regulation of mitfa accounts for the sox10 requirement in zebrafish melanophore development. Development 130, 2809–2818 (2003).

Carroll, S. B., Grenier, J. K. & Weatherbee, S. D. From DNA to Diversity, Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design 2nd edn (Blackwell, Oxford, 2005).

Poelstra, J. W., Vijay, N., Hoeppner, M. P. & Wolf, J. B. W. Transcriptomics of colour patterning and coloration shifts in crows. Mol. Ecol. 24, 4617–4628 (2015).

Jeong, S., Rokas, A. & Carroll, S. B. Regulation of body pigmentation by the Abdominal-B Hox protein and its gain and loss in Drosophila evolution. Cell 125, 1387–1399 (2006).

Saenko, S. V., Marialva, M. S. & Beldade, P. Involvement of the conserved Hox gene Antennapedia in the development and evolution of a novel trait. EvoDevo 2, 9 (2011).

Thummel, R., Li, L., Tanase, C., Sarras, M. P. & Godwin, A. R. Differences in expression pattern and function between zebrafish hoxc13 orthologs: recruitment of Hoxc13b into an early embryonic role. Dev. Biol. 274, 318–333 (2004).

Jakovlić, I. & Wang, W.-M. Expression of Hox paralog group 13 genes in adult and developing Megalobrama amblycephala. Gene Expr. Patterns 21, 63–68 (2016).

Mattar, P., Ericson, J., Blackshaw, S. & Cayouette, M. A conserved regulatory logic controls temporal identity in mouse neural progenitors. Neuron 85, 497–504 (2015).

Yokoyama, S. Evolution of dim-light and color vision pigments. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 9, 259–282 (2008).

Bierne, N. The distinctive footprints of local hitchhiking in a varied environment and global hitchhiking in a subdivided population. Evolution 64, 3254–3272 (2010).

Roesti, M., Gavrilets, S., Hendry, A. P., Salzburger, W. & Berner, D. The genomic signature of parallel adaptation from shared genetic variation. Mol. Ecol. 23, 3944–3956 (2014).

Feder, J. L. & Nosil, P. The efficacy of divergence hitchhiking in generating genomic islands during ecological speciation. Evolution 64, 1729–1747 (2010).

Parichy, D. M. et al. Mutational analysis of endothelin receptor b1 (rose) during neural crest and pigment pattern development in the zebrafish Danio rerio. Dev. Biol. 227, 294–306 (2000).

Curran, K., Raible, D. W. & Lister, J. A. Foxd3 controls melanophore specification in the zebrafish neural crest by regulation of Mitf. Dev. Biol. 332, 408–417 (2009).

Jia, L. et al. Retinoid-related orphan nuclear receptor RORβ is an early-acting factor in rod photoreceptor development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17534–17539 (2009).

Zhao, C. & Malicki, J. Nephrocystins and MKS proteins interact with IFT particle and facilitate transport of selected ciliary cargos. EMBO J. 30, 2532–2544 (2011).

Ravinet, M. et al. Interpreting the genomic landscape of speciation: a road map for finding barriers to gene flow. J. Evol. Biol. 30, 1450–1477 (2017).

Wolf, J. B. & Ellegren, H. Making sense of genomic islands of differentiation in light of speciation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 87–100 (2017).

Charlesworth, B., Morgan, M. & Charlesworth, D. The effect of deleterious mutations on neutral molecular variation. Genetics 134, 1289–1303 (1993).

Guerrero, R. F. & Hahn, M. W. Speciation as a sieve for ancestral polymorphism. Mol. Ecol. 26, 5362–5368 (2017).

Burri, R. Interpreting differentiation landscapes in the light of long-term linked selection. Evol. Lett. 1, 118–131 (2017).

Noor, M. A. F. & Feder, J. L. Speciation genetics: evolving approaches. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 851–861 (2006).

Cruickshank, T. E. & Hahn, M. W. Reanalysis suggests that genomic islands of speciation are due to reduced diversity, not reduced gene flow. Mol. Ecol. 23, 3133–3157 (2014).

Flaxman, S. M., Wacholder, A. C., Feder, J. L. & Nosil, P. Theoretical models of the influence of genomic architecture on the dynamics of speciation. Mol. Ecol. 23, 4074–4088 (2014).

Slatkin, M. Linkage disequilibrium—understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 477–485 (2008).

Tine, M. et al. European sea bass genome and its variation provide insights into adaptation to euryhalinity and speciation. Nat. Commun. 5, 5770 (2014).

Feulner, P. G. et al. Genomics of divergence along a continuum of parapatric population differentiation. PLoS Genet. 11, e1004966 (2015).

Meier, J. I., Marques, D. A., Wagner, C. E., Excoffier, L. & Seehausen, O. Genomics of parallel ecological speciation in Lake Victoria cichlids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1489–1506 (2018).

Puebla, O., Bermingham, E. & Guichard, F. Perspective: matching, mate choice, and speciation. Integr. Comp. Biol. 51, 485–491 (2011).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Leggett, R. M., Clavijo, B. J., Clissold, L., Clark, M. D. & Caccamo, M. NextClip: an analysis and read preparation tool for Nextera Long Mate Pair libraries. Bioinformatics 30, 566–568 (2014).

Wood, D. E. & Salzberg, S. L. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46 (2014).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Vij, S. et al. Chromosomal-level assembly of the Asian seabass genome using long sequence reads and multi-layered scaffolding. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005954 (2016).

Hackl, T., Hedrich, R., Schultz, J. & Förster, F. proovread: large-scale high-accuracy PacBio correction through iterative short read consensus. Bioinformatics 30, 3004–3011 (2014).

Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data (Babraham Institute, 2012); https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Kajitani, R. et al. Efficient de novo assembly of highly heterozygous genomes from whole-genome shotgun short reads. Genome Res. 24, 1384–1395 (2014).

English, A. C. et al. Mind the gap: upgrading genomes with Pacific Biosciences RS long-read sequencing technology. PLoS ONE 7, e47768 (2012).

Tang, H. et al. ALLMAPS: robust scaffold ordering based on multiple maps. Genome Biol. 16, 3 (2015).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Roesti, M., Moser, D. & Berner, D. Recombination in the threespine stickleback genome—patterns and consequences. Mol. Ecol. 22, 3014–3027 (2013).

Kiełbasa, S. M., Wan, R., Sato, K., Horton, P. & Frith, M. C. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome Res. 21, 487–493 (2011).

Krzywinski, M. I. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645 (2009).

Simão, F. A. et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Smit, A. F. A. & Hubley, R. RepeatModeler Open-1.0 (Institute for Systems Biology, 2008); http://www.repeatmasker.org

Smit, A. F. A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0 (Institute for Systems Biology, 2013-2015); http://www.repeatmasker.org

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011).

Campbell, M. S., Holt, C., Moore, B. & Yandell, M. Genome annotation and curation using MAKER and MAKER-P. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 48, 4.11.1–4.11.39 (2012).

The UniProt Consortium UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 2699 (2018).

Finn, R. D. et al. InterPro in 2017—beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D190–D199 (2017).

Lee, E. et al. Web Apollo: a web-based genomic annotation editing platform. Genome Biol. 14, R93 (2013).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

DePristo, M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011).

Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high-confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 43, 11.10.1–11.10.33 (2013).

Picard (Broad Institute, 2015); http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Martin, S. H. genomics_general: general tools for genomic analyses. GitHub https://github.com/simonhmartin/genomics_general.git (2016).

Delaneau, O., Marchini, J. & Zagury, J.-F. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat. Methods 9, 179–181 (2012).

Luu, K. & Blum, M. pcadapt: Fast principal component analysis for outlier detection. R package version 3.0.4 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pcadapt (2017).

Nei, M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics (Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 1987).

Weir, B. S. & Cockerham, C. C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38, 1358–1370 (1984).

Zhou, X. & Stephens, M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat. Genet. 44, 821–824 (2012).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Anderson, E. C. & Thompson, E. A. A model-based method for identifying species hybrids using multilocus genetic data. Genetics 160, 1217–1229 (2002).

Lischer, H. E. L. & Excoffier, L. PGDSpider: an automated data conversion tool for connecting population genetics and genomics programs. Bioinformatics 28, 298–299 (2012).

Wringe, B., Stanley, R., Jeffery, N., Anderson, E. & Bradbury, I. parallelnewhybrid: an R package for the parallelization of hybrid detection using NEWHYBRIDS. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17, 91–95 (2016).

Gao, F., Ming, C., Hu, W. & Li, H. New software for the fast estimation of population recombination rates (FastEPRR) in the genomic era. G3 6, 1563–1571 (2016).

Pertea, G. gffread: GFF/FTF utility providing format conversions, region filtering, FASTA sequence extraction and more. GitHub https://github.com/gpertea/gffread.git (2015).

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-Seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 525–527 (2016).

Love, M., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Ewing, G. & Hermisson, J. MSMS: a coalescent simulation program including recombination, demographic structure and selection at a single locus. Bioinformatics 26, 2064–2065 (2010).

Rambaut, A. & Grass, N. C. Seq-Gen: an application for the Monte Carlo simulation of DNA sequence evolution along phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 13, 235–238 (1997).

Lindenbaum, P. JVarkit: java-based utilities for bioinformatics. Figshare https://figshare.com/articles/JVarkit{_}java{_}based{_}utilities{_}for{_}Bioinformatics/1425030 (2015).

Di Tommaso, P. et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 316–319 (2017).

Xie, Y. bookdown: Authoring Books and Technical Documents with R Markdown (Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, 2016).

Ihaka, R., Murrell, P., Hornik, K., Fisher, J. C. & Zeileis, A. colorspace: Color space manipulation. R package version 1.3-2 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=colorspace (2016).

Wilke, C. O. cowplot: Streamlined plot theme and plot annotations for ’ggplot2′. R package version 0.9.2 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cowplot (2017).

Wickham, H., Francois, R., Henry, L. & Müller, K. dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation. R package version 0.7.4 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (2017).

Warnes, G. R. et al. gdata: Various R programming tools for data manipulation. R package version 2.18.0 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gdata (2017).

Pedersen, T. L. ggforce: Accelerating ’ggplot2′. R package version 0.1.2 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggforce (2018).

Kahle, D. & Wickham, H. ggmap: Spatial visualization with ggplot2. R J. 5, 144–181 (2013).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, New York, 2016).

Slowikowski, K. ggrepel: Repulsive text and label geoms for ’ggplot2′. R package version 0.7.0 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggrepel (2017).

Warnes, G. R. et al. gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data. R package version 3.0.1 https: //CRAN.R-project.org/package=gplots (2016).

Potter, S. grConvert: Converting vector graphics. R package version 0.1-0. (2013).

Auguie, B. gridExtra: Miscellaneous functions for “grid” graphics. R package version 2.3 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gridExtra (2017).

Murrell, P. & Potter, S. gridSVG: Export ’grid’ graphics as SVG. R package version 1.6-0 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gridSVG (2017).

Potter, S. grImport2: Importing ’SVG’ graphics. R package version 0.1-4 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=grImport2 (2018).

Wickham, H. gtable: Arrange ’grobs’ in tables. R package version 0.2.0 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gtable (2016).

Rudis, B. hrbrthemes: Additional themes, theme components and utilities for ’ggplot2′. R package version 0.1.0 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=hrbrthemes (2017).

Xie, Y. knitr: A general-purpose package for dynamic report generation in R. R package version 1.20 https://yihui.name/knitr/ (2018).

Xie, Y. Dynamic Documents with R and knitr 2nd edn (Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, 2015).

Xie, Y. in Implementing Reproducible Research (eds Stodden, V., Leisch, F. & Peng, R. D.)3–32 (Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, 2014).

Bivand, R. & Lewin-Koh, N. maptools: Tools for reading and handling spatial objects. R package version 0.9-2 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=maptools (2017).

Pante, E. & Simon-Bouhet, B. marmap: a package for importing, plotting and analyzing bathymetric and topographic data in R. PLoS ONE 8, e73051 (2013).

Schnute, J. T., Boers, N. & Haigh, R. PBSmapping: mapping fisheries data and spatial analysis tools. R package version 2.70.4 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=PBSmapping (2017).

Neuwirth, E. RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer palettes. R package version 1.1-2 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RColorBrewer (2014).

Lawrence, M., Gentleman, R. & Carey, V. rtracklayer: An R package for interfacing with genome browsers. Bioinformatics 25, 1841–1842 (2009).

Wickham, H. scales: Scale functions for visualization. R package version 0.5.0.9000 https://github.com/hadley/scales (2017).

Yu, G. scatterpie: Scatter pie plot. R package version 0.0.9 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scatterpie (2018).

Pebesma, E. J. & Bivand, R. S. Classes and methods for spatial data in R. R News 5, 9–13 (2005).

Bivand, R. S., Pebesma, E. & Gomez-Rubio, V. Applied Spatial Data Analysis with R 2nd edn (Springer, New York, 2013).

Wickham, H. tidyverse: Easily install and load the ’tidyverse’. R package version 1.2.1 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyverse (2017).

Soneson, C., Love, M. I. & Robinson, M. D. Differential analyses for RNA-Seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res 4, 1521 (2015).

Huber, W., von Heydebreck, A., Sueltmann, H., Poustka, A. & Vingron, M. Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics 18, S96–S104 (2002).

Robertson, D. R. & Tassell, J. V. Shorefishes of the Greater Caribbean: online information system. Version 1.0 (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, 2015); http://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/caribbean/en/research/index/range

Xie, Y. bookdown: Authoring books and technical documents with R Markdown. GitHub https://github.com/rstudio/bookdown (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an individual German Research Foundationgrant to O.P. (PU571/1–1) and a grant from the Smithsonian Institute for Biodiversity Genomics and Global Genome Initiative Grants Program to W.O.M., O.P. and C. Baldwin. The authors thank T. Bayer, B. Bermingham, K. Fietz, P. Frandsen, B. Haubold, C. Jiggins, R. Merrill, T. Reusch, M. Torres Oliva and S. Van Belleghem, as well as the Belizean, Honduran and Panamanian authorities, for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.P., W.O.M. and K.H. designed the study and participated in the sampling. K.H., M.V. and O.P. contributed to the DNA extractions. M.V. prepared part of the DNA and all of the RNA libraries. K.H. assembled the hamlet genome and conducted the data analyses, in collaboration with O.P. and W.O.M. M.P.H. annotated the genome and contributed to the sequencing. All authors contributed to the writing, with major input from K.H., O.P. and W.O.M.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1–17 and Supplementary Tables 1–8

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hench, K., Vargas, M., Höppner, M.P. et al. Inter-chromosomal coupling between vision and pigmentation genes during genomic divergence. Nat Ecol Evol 3, 657–667 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0814-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0814-5

This article is cited by

-

Allorecognition genes drive reproductive isolation in Podospora anserina

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022)

-

Correlational selection in the age of genomics

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2021)

-

Stable species boundaries despite ten million years of hybridization in tropical eels

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Visual mate preference evolution during butterfly speciation is linked to neural processing genes

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Ecology shapes epistasis in a genotype–phenotype–fitness map for stick insect colour

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2020)