Abstract

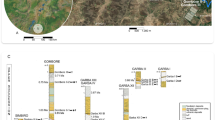

Despite its largely hyper-arid and inhospitable climate today, the Arabian Peninsula is emerging as an important area for investigating Pleistocene hominin dispersals. Recently, a member of our own species was found in northern Arabia dating to ca. 90 ka, while stone tools and fossil finds have hinted at an earlier, middle Pleistocene, hominin presence. However, there remain few direct insights into Pleistocene environments, and associated hominin adaptations, that accompanied the movement of populations into this region. Here, we apply stable carbon and oxygen isotope analysis to fossil mammal tooth enamel (n = 21) from the middle Pleistocene locality of Ti’s al Ghadah in Saudi Arabia associated with newly discovered stone tools and probable cutmarks. The results demonstrate productive grasslands in the interior of the Arabian Peninsula ca. 300–500 ka, as well as aridity levels similar to those found in open savannah settings in eastern Africa today. The association between this palaeoenvironmental information and the earliest traces for hominin activity in this part of the world lead us to argue that middle Pleistocene hominin dispersals into the interior of the Arabian Peninsula required no major novel adaptation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Gamble, C. Timewalkers: The Prehistory of Global Colonization (Alan Sutton, Gloucester, 1993).

Gamble, C. Settling the Earth: The Archaeology of Deep Human History (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2013).

Roberts, P. & Stewart, B. A. Defining the ‘generalist specialist’ niche for Pleistocene Homo sapiens. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 542–550 (2018).

Dennell, R. & Roebroeks, W. An Asian perspective on early human dispersal from Africa. Nature 438, 1099–1104 (2005).

Joordens, J. C. A. et al. Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving. Nature 518, 228–231 (2016).

Hoffman, D. L. et al. U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberial cave art. Science 359, 912–915 (2018).

Morwood, M. J., O’Sullivan, P. B., Aziz, F. & Raza, A. Fission-track ages of stone tools and fossils on the east Indonesian island of Flores. Nature 392, 173–176 (1998).

Zhu, R. X. et al. Early evidence of the genus Homo in East Asia. J. Hum. Evol. 55, 1075–1085 (2008).

Parfitt, S. A. et al. Early Pleistocene human occupation at the edge of the boreal zone in northwest Europe. Nature 466, 229–233 (2010).

Jennings, R. P. et al. The greening of Arabia: multiple opportunities for human occupation in the Arabian Peninsula during the late Pleistocene inferred from an ensemble of climate model simulations. Quat. Int 382, 181–199 (2015).

Fleitmann, D., Burns, S. J., Neff, U., Mangini, A. & Matter, A. Changing moisture sources over the last 333,000 years in northern Oman from fluid-inclusion evidence in speleothems. Quat. Res. 60, 223–232 (2003).

Thomas, H. et al. First Pleistocene faunas from the Arabian Peninsula: An Nafud desert, Saudi Arabia. C. R. Acad. Sci. II 326, 145–152 (1998).

Stimpson, C. M. et al. Stratified Pleistocene vertebrates with a new record of a jaguar-sized pantherine (Panthera cf. gombaszogensis) from northern Saudi Arabia. Quat. Int. 382, 168–180 (2015).

Stimpson, C. M. et al. Middle Pleistocene vertebrate fossils from the Nefud Desert, Saudi Arabia:implications for biogeography and palaeoecology. Quat. Sci. Rev. 143, 13–36 (2016).

Stewart, M. et al. Middle and late Pleistocene mammal fossils of Arabia and surrounding regions: implications for biogeography and hominin dispersals. Quat. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.11.052 (2017).

Rosenberg, T. M. et al. Middle and late Pleistocene humid periods recorded in palaeolake deposits of the Nafud desert, Saudi Arabia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 70, 109–123 (2013).

Parton, A. et al. Alluvial fan records from southeast Arabia reveal multiple windows for human dispersal. Geology 43, 295–298 (2015).

Groucutt, H. S. et al. Human occupation of the Arabian Empty Quarter during MIS 5: evidence from Mundafan Al-Buhayrah, Saudi Arabia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 119, 116–135 (2015).

Breeze, P. S. et al. Palaeohydrological corridors for hominin dispersals in the Middle East ~250–70,000 years ago. Quat. Sci. Rev. 144, 155–185 (2016).

Groucutt, H. S. et al. Homo sapiens in Arabia by 85,000 years ago. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 800–809 (2018).

Armitage, S. J. et al. The southern route “out of Africa”: evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia. Science 331, 453–456 (2011).

Petraglia, M. et al. Middle Paleolithic occupation on a Marine Isotope Stage 5 lakeshore in the Nefud Desert, Saudi Arabia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 1555–1559 (2011).

Petraglia, M. D. et al. Hominin dispersal into the Nefud Desert and middle Palaeolithic settlement along the Jubbah Palaeolake, northern Arabia. PLoS ONE 7, e49840 (2012).

Scerri, E. M. L. et al. Middle to late Pleistocene human habitation in the Nefud Desert, Saudi Arabia. Quat. Int. 382, 200–214 (2015).

Lee-Thorp, J. A., Sealy, J. C. & van der Merwe, N. J. Stable carbon isotope ratio differences between bone collagen and bone apatite, and their relationship to diet. J. Archaeol. Sci. 16, 585–599 (1989).

Lee-Thorp, J. A., van der Merwe, N. J. & Brain, C. K. Isotopic evidence for dietary differences between two extinct baboon species from Swartkrans. J. Hum. Evol. 18, 183–189 (1989).

Levin, N. E., Simpson, S. W., Quade, J., Cerling, T. E. & Frost, S. R. in The Geology of Early Humans in the Horn of Africa (eds Quade, J. & Wynn, J. G.) 215–234 (Geological Society of America, Boulder, 2008).

Calvin, M. & Benson, A. A. The path of carbon in photosynthesis. Science 107, 476–480 (1948).

Hatch, M., Slack, C. R. & Johnson, H. S. Further studies on a new pathway of photosynthetic carbon dioxide fixation in sugar-cane and its occurrence in other plant species. Biochem. J. 102, 417–422 (1967).

Tieszen, L. L. Natural variations in the carbon isotope values of plants: implications for archaeology, ecology, and paleoecology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 18, 227–248 (1991).

Flanagan, L. B., Comstock, J. P. & Ehleringer, J. R. Comparison of modeled and observed environmental influences on the stable oxygen and hydrogen isotope composition of leaf water in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Plant Physiol. 96, 588–596 (1991).

Barbour, M. M. Stable oxygen isotope composition of plant tissue: a review. Funct. Plant Biol. 34, 83–94 (2007).

Levin, N. E., Cerling, T. E., Passey, B. H., Harris, J. M. & Ehleringer, J. R. A stable isotope aridity index for terrestrial environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11201–11205 (2006).

Blumenthal, S. A. et al. Aridity and hominin environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7331–7336 (2017).

Balasse, M. Reconstructing dietary and environmental history from enamel isotopic analysis: time resolution of intra-tooth sequential sampling. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 12, 155–165 (2002).

Roberts, P. et al. Fruits of the forest: human stable isotope ecology and rainforest adaptations in late Pleistocene and Holocene (~36 to 3 ka) Sri Lanka. J. Hum. Evol. 106, 102–118 (2017).

Pineda, A. et al. Trampling versus cut marks on chemically altered surfaces: an experimental approach and archaeological application at the Barranc de la Boella site (la Canonja, Tarragona, Spain). J. Archaeol. Sci. 50, 84–93 (2014).

Pickering, T. R. et al. Taphonomy of ungulate ribs and the consumption of meat and bone by 1.2-million-year-old hominins at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 1295–1309 (2013).

Sponheimer, M. & Lee-Thorp, J. A. Isotopic evidence for the diet of an early hominid, Australopithecus africanus. Science 283, 368–370 (1999).

Sponheimer, M. & Lee-Thorp, J. A. The oxygen isotope composition of mammalian enamel carbonate from Morea Estate, South Africa. Oecologia 126, 153–157 (2001).

Cerling, T. E. et al. Stable isotopes in elephant hair document migration patterns and diet changes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 371–373 (2006).

Ingicco, T. et al. Earliest known hominin activity in the Philippines by 709 thousand years ago. Nature 557, 233–237 (2018).

Parker, A. G. in The Evolution of Human Populations in Arabia: Paleoenvironments, Prehistory and Genetics (eds Petraglia, M. D. & Rose, J. I .) 39–49 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2010).

Drake, N. A., Breeze, P. & Parker, A. Palaeoclimate in the Saharan and Arabian deserts during the middle Palaeolithic and the potential for hominin dispersals. Quat. Int 300, 48–61 (2013).

Martínez-Navarro, B. in Human Palaeoecology in the Levantine Corridor (eds Goren-Inbar, N. & Speth, J. D.) 37–52 (Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2004).

Potts, R. Hominin evolution in settings of strong environmental variability. Quat. Sci. Rev. 73, 1–13 (2013).

Delagnes, A. et al. Inland human settlement in southern Arabia 55,000 years ago. New evidence from the Wadi Surdud middle Paleolithic site complex, western Yemen. J. Hum. Evol. 63, 452–474 (2012).

Breeze, P. Prehistory and palaeoenvironments of the western Nefud Desert, Saudi Arabia. Archaeol. Res. Asia 10, 1–16 (2017).

Nash, D. J. et al. Going the distance: mapping mobility in the Kalahari Desert during the middle Stone Age through multi-site geochemical provenancing of silcrete artefacts. J. Hum. Evol. 96, 113–133 (2016).

Dewar, G. & Stewart, B. A. in Africa from MIS 6-2: Population Dynamics and Paleoenvironments (eds Jones, S. C. & Stewart, B. A.) 195–212 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2016).

Scerri, E. M. L., Drake, N. A., Jennings, R. & Groucutt, H. S. Earliest evidence for the structure of Homo sapiens populations in Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 101, 207–216 (2014).

Capaldo, S. D. & Blumenschine, R. J. A quantitative diagnosis of notches made by hammerstone percussion and carnivore gnawing on bovid long bones. Am. Antiq. 59, 724–748 (1994).

Fisher, J. W. Jr Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2, 7–68 (1995).

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M., de Juana, S., Galán, A. B. & Rodríguez, M. A new protocol to differentiate trampling marks from butchery cut marks. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 2643–2654 (2009).

Galán, A. B., Rodríguez, M., de Juana, S. & Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. A new experimental study on percussion marks and notches and their bearing on the interpretation of hammerstone-broken faunal assemblages. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 776–784 (2009).

Sponheimer, M. et al. Hominins, sedges, and termites: new carbon isotope data from the Sterkfontein valley and Kruger National Park. J. Hum. Evol. 48, 301–312 (2005).

Lee-Thorp, J. A. et al. Isotopic evidence for an early shift to C4 resources by Pliocene hominins in Chad. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 20369–20372 (2012).

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank HRH Prince Sultan bin Salman, President of the Saudi Commission for Tourism & National Heritage (SCTH) and Vice Presidents A. Ghabban and J. Omar for permission to conduct this study. This project was funded by the European Research Council (grant no. 295719 to M.D.P.), the Max Planck Society, and the SCTH. Z. Nawab, former President of the Saudi Geological Survey, provided research support. We thank A. Gledhill, University of Bradford, for his assistance with the stable isotope analysis. We thank K. Privat of the Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre (UNSW) for assistance with SEM imagery. H.S.G. and E.M.L.S. acknowledge the British Academy for funding. M.S acknowledges The Leakey Foundation for funding. ANA acknowledges the Deanship of Scientific Research at the King Saud University through Vice Deanship of Research Chairs for their additional funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.R., M.S. and M.P. planned the project. P.R., M.S., A.N.A., P.B., H.S.G., E.M.L.S., J.L.T., J.L., J.Z. and I.S.Z. performed the experiments. P.R., M.S., A.N.A., P.B., H.S.G., E.M.L.S., J.L.T., J.L., J.Z. and I.S.Z. performed the data analysis. All authors interpreted the data. All authors wrote and provided comment on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Text, Figures, Tables and References

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts, P., Stewart, M., Alagaili, A.N. et al. Fossil herbivore stable isotopes reveal middle Pleistocene hominin palaeoenvironment in ‘Green Arabia’. Nat Ecol Evol 2, 1871–1878 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0698-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0698-9

This article is cited by

-

Adaptive foraging behaviours in the Horn of Africa during Toba supereruption

Nature (2024)

-

Multiple phases of human occupation in Southeast Arabia between 210,000 and 120,000 years ago

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The expansion of Acheulean hominins into the Nefud Desert of Arabia

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Earliest Olduvai hominins exploited unstable environments ~ 2 million years ago

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Isotopic evidence for initial coastal colonization and subsequent diversification in the human occupation of Wallacea

Nature Communications (2020)