Abstract

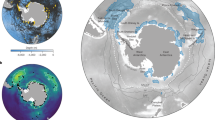

During their migrations, marine predators experience varying levels of protection and face many threats as they travel through multiple countries’ jurisdictions and across ocean basins. Some populations are declining rapidly. Contributing to such declines is a failure of some international agreements to ensure effective cooperation by the stakeholders responsible for managing species throughout their ranges, including in the high seas, a global commons. Here we use biologging data from marine predators to provide quantitative measures with great potential to inform local, national and international management efforts in the Pacific Ocean. We synthesized a large tracking data set to show how the movements and migratory phenology of 1,648 individuals representing 14 species—from leatherback turtles to white sharks—relate to the geopolitical boundaries of the Pacific Ocean throughout species’ annual cycles. Cumulatively, these species visited 86% of Pacific Ocean countries and some spent three-quarters of their annual cycles in the high seas. With our results, we offer answers to questions posed when designing international strategies for managing migratory species.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Block, B. A. et al. Tracking apex marine predator movements in a dynamic ocean. Nature 475, 86–90 (2011).

Halpern, B. S. et al. A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 319, 948–952 (2008).

Tapilatu, R. F. et al. Long-term decline of the western Pacific leatherback, Dermochelys coriacea: a globally important sea turtle population. Ecosphere 4, 1–15 (2013).

2016 Pacific Bluefin Tuna Stock Assessment: Report of the Pacific Tuna Working Group (International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-Like Species in the North Pacific Ocean, 2016); http://isc.fra.go.jp/pdf/ISC16/ISC16_Annex_09_2016_Pacific_Bluefin_Tuna_Stock_Assessment.pdf

Dulvy, N. K. et al. Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. ELife 3, e00590 (2014).

Croxall, J. P. et al. Seabird conservation status, threats and priority actions: a global assessment. Bird. Conserv. Int. 22, 1–34 (2012).

Lascelles, B. et al. Migratory marine species: their status, threats and conservation management needs. Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 24, 111–127 (2014).

Mora, C. et al. Management effectiveness of the world’s marine fisheries. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000131 (2009).

Cullis-Suzuki, S. & Pauly, D. Failing the high seas: a global evaluation of regional fisheries management organizations. Mar. Policy 34, 1036–1042 (2010).

Gilman, E., Passfield, K. & Nakamura, K. Performance of regional fisheries management organizations: ecosystem-based governance of bycatch and discards. Fish Fish. Fish. (Oxf) 15, 327–351 (2014).

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (United Nations, 1982).

United Nations Conference on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks: Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982, Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (United Nations, 1995).

Wood, S. N., Pya, N. & Säfken, B. Smoothing parameter and model selection for general smooth models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 111, 1548–1575 (2016).

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA 2006).

Shaffer, S. A. et al. Migratory shearwaters integrate oceanic resources across the Pacific Ocean in an endless summer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12799–12802 (2006).

Weise, M. J., Costa, D. P. & Kudela, R. M. Movement and diving behavior of male California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) during anomalous oceanographic conditions of 2005 compared to those of 2004. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L22S10 (2006).

Lyons, K. et al. The degree and result of gillnet fishery interactions with juvenile white sharks in southern California assessed by fishery-independent and -dependent methods. Fish. Res. 147, 370–380 (2013).

Domeier, M. L. & Nasby-Lucas, N. Migration patterns of white sharks Carcharodon carcharias tagged at Guadalupe Island, Mexico, and identification of an eastern Pacific shared offshore foraging area. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 370, 221–237 (2008).

Wallace, B. P., Tiwari, M. & Girondot, M. Dermochelys coriacea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: e.T6494A43526147 (2013); https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T6494A43526147.en

Dutton, P. H. & Squires, D. Reconciling biodiversity with fishing: a holistic strategy for Pacific sea turtle recovery. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 39, 200–222 (2008).

Dutton, P. H. & Squires, D. in Conservation of Pacific Sea Turtles (eds Dutton, P. H. et al.) 1–23 (Univ. Hawaii Press, Honolulu, HI, USA, 2011).

Russ, G. R. & Zeller, D. C. From Mare Liberum to Mare Reservarum. Mar. Policy 27, 75–78 (2003).

Lubchenco, J. & Grorud-Colvert, K. OCEAN. Making waves: the science and politics of ocean protection. Science 350, 382–383 (2015).

Cressey, D. Talks aim to tame marine Wild West: nations debate how to protect biodiversity in the high seas.Nature 532, 18–19 (2016).

McCauley, D. J. et al. Ending hide and seek at sea. Science 351, 1148–1150 (2016).

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS, Bonn, Germany, 1979).

Hussey, N. E. et al. Aquatic animal telemetry: a panoramic window into the underwater world. Science 348, 1255642 (2015).

Burger, A. E. & Shaffer, S. A. Application of tracking and data-logging technology in research and conservation of seabirds. Auk 125, 253–264 (2008).

Lascelles, B. G. et al. Applying global criteria to tracking data to define important areas for marine conservation. Divers. Distrib. 22, 422–431 (2016).

Ogburn, M. B.et al. Addressing challenges in the application of animal movement ecology to aquatic conservation and management. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 70 (2017).

Jonsen, I. D., Flemming, J. M. & Myers, R. A. Robust state–space modeling of animal movement data. Ecology 86, 2874–2880 (2005).

Winship, A. J. et al. State–space framework for estimating measurement error from double-tagging telemetry experiments. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 291–302 (2012).

Shillinger, G. L. et al. Persistent leatherback turtle migrations present opportunities for conservation. PLoS Biol 6, e171 (2008).

Benson, S. R. et al. Large-scale movements and high-use areas of western Pacific leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea. Ecosphere 2, 1–27 (2011).

Suryan, R. M. et al. Migratory routes of short-tailed albatrosses: use of exclusive economic zones of North Pacific Rim countries and spatial overlap with commercial fisheries in Alaska. Biol. Conserv. 137, 450–460 (2007).

Wood, S. N. Mixed GAM computation vehicle with automatic smoothness estimation v. 1.8-24 (CRAN, 2018); https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mgcv/mgcv.pdf

Acknowledgements

This article is a product of the Census of Marine Life Tagging of the TOPP Project. Funding for this work was provided by the Sloan Foundation’s Census of Marine Life programme. TOPP research was funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation with additional support from the Office of Naval Research, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the E&P Sound and Marine Life Joint Industry Programme under contract from the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, donors to the Oregon State University Marine Mammal Institute, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. A.-L.H. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, a University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) M.R.C. Greenwood Fellowship in Interdisciplinary Environmental Research, a UCSC Graduate Division Dissertation Year Fellowship, the UCSC Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department, the UCSC Center for the Dynamics and Evolution of the Land-Sea Interface, the American Cetacean Society, Monterey Bay Chapter, a UCSC Marilyn C. and Raymond E. Davis Memorial Scholarship Professional Development Award, the Institute for Parks at Clemson University, and by the ConocoPhillips Global Signature Programme. We thank the TOPP scientific teams and all those who contributed to tag deployment efforts, including international partners in Canada, Indonesia, Mexico, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and Solomon Islands, the numerous captains and crews who provided ship time and logistical support, the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Hawaii, and many graduate students and undergraduate researchers and volunteers. We thank the TOPP data management team (A. Swithenbank, J.E. Ganong and M. Castleton) and the Future of Marine Animal Populations Project of the Census of Marine Life (FMAP) tracking data modelling and compilation team (I.D. Jonsen and G.A. Breed). Earlier versions of this article were improved by discussions with B. Abrahms, A.M. Boustany, M.H. Carr, M. Dias and P.P. Marra.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conceived by A.-L.H. The TOPP project was designed and coordinated by B.A.B., D.P.C. and S.J.B. B.A.B., A.B.C., H.D., S.J.J., S.K., K.M.S., G.L.S and K.C.W. designed the experiments and deployed the electronic tags on fish and sharks. S.R.B., P.H.D., G.L.S. and B.A.B., designed the experiments and deployed the electronic tags on leatherback sea turtles. D.P.C., P.W.R., S.E.S. and B.R.M. designed the experiments and deployed the electronic tags on marine mammals. S.A.S. and M.A. designed the experiments and deployed the electronic tags on seabirds. Analyses were conducted by A.-L.H. and A.J.W. Figures were created by A.-L.H. The manuscript was drafted by A.-L.H. and edited by D.P.C., A.J.W., S.R.B., S.J.B., A.B.C., H.D., P.H.D, S.J.J., M.A., S.K., S.A.S., K.M.S., G.L.S., S.E.S., K.C.W. and B.A.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Kristina Gjerde is an unpaid member of the Sargasso Sea Project, Inc. Board, the Global Ocean Biodiversity Initiative Scientific Steering Committee, the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative Executive Board, the High Seas Alliance Steering Committee, and the Deep Ocean Observing Strategy Scientific Steering Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1–10; Supplementary Tables 1–5; Supplementary References

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harrison, AL., Costa, D.P., Winship, A.J. et al. The political biogeography of migratory marine predators. Nat Ecol Evol 2, 1571–1578 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0646-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0646-8

This article is cited by

-

Thermal vulnerability of sea turtle foraging grounds around the globe

Communications Biology (2024)

-

Beyond boundaries: governance considerations for climate-driven habitat shifts of highly migratory marine species across jurisdictions

npj Ocean Sustainability (2024)

-

A vision for incorporating human mobility in the study of human–wildlife interactions

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Impacts of marine heatwaves on top predator distributions are variable but predictable

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Basin-scale biogeochemical and ecological impacts of islands in the tropical Pacific Ocean

Nature Geoscience (2022)