Abstract

The impact of climate change on migration has gained both academic and public interest in recent years. Here we employ a meta-analysis approach to synthesize the evidence from 30 country-level studies that estimate the effect of slow- and rapid-onset events on migration worldwide. Most studies find that environmental hazards affect migration, although with contextual variation. Migration is primarily internal or to low- and middle-income countries. The strongest relationship is found in studies with a large share of countries outside the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, particularly from Latin America and the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa, and in studies of middle-income and agriculturally dependent countries. Income and conflict moderate and partly explain the relationship between environmental change and migration. Combining our estimates for differential migration responses with the observed environmental change in these countries in recent decades illustrates how the meta-analytic results can provide useful insights for the identification of potential hotspots of environmental migration.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The meta-data and country-level data generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository107, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/Meta-Analysis_EnvironmentalMigration.

Code availability

The data analysis was carried out in R108. The complete codes used to generate and visualize the results reported in this study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository107, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/Meta-Analysis_EnvironmentalMigration. All used packages are acknowledged and cited in the source code file.

References

Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M. A., Seager, R. & Kushnir, Y. Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3241–3246 (2015).

Gleick, P. H. Water, drought, climate change, and conflict in Syria. Weather Clim. Soc. 6, 331–340 (2014).

De Châtel, F. The role of drought and climate change in the Syrian uprising: untangling the triggers of the revolution. Middle East. Stud. 50, 521–535 (2014).

Selby, J., Dahi, O. S., Fröhlich, C. & Hulme, M. Climate change and the Syrian civil war revisited. Polit. Geogr. 60, 232–244 (2017).

Myers, N. Environmental refugees: a growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 357, 609–613 (2002).

Renaud, F., Bogardi, J. J., Dun, O. & Warner, K. Control, Adapt or Flee: How to Face Environmental Migration? InterSecTions, Publication Series of United Nations University, ENS Vol. 5 (United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security, 2007).

Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006).

Biermann, F. & Boas, L. Preparing for a warmer world: towards a global governance system to protect climate refugees. Glob. Environ. Polit. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2010.10.1.60 (2010).

Cattaneo, C. et al. Human migration in the era of climate change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 13, 189–206 (2019).

Berlemann, M. & Steinhardt, M. F. Climate change, natural disasters, and migration—a survey of the empirical evidence. CESifo Econ. Stud. 63, 353–385 (2017).

Hunter, L. M., Luna, J. K. & Norton, R. M. Environmental dimensions of migration. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41, 377–397 (2015).

Piguet, E. Linking climate change, environmental degradation, and migration: a methodological overview. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 1, 517–524 (2010).

Borderon, M. et al. Migration influenced by environmental change in Africa: a systematic review of empirical evidence. Demogr. Res. 41, 491–544 (2019).

Black, R., Stephen, R., Bennett, G., Thomas, S. M. & Beddington, J. R. Migration as adaptation. Nature 478, 447–449 (2011).

Barrios, S., Bertinelli, L. & Strobl, E. Climatic change and rural-urban migration: the case of sub-Saharan Africa. J. Urban Econ. 60, 357–371 (2006).

Naudé, W. Natural disasters and international migration from sub-Saharan Africa. Migrat. Lett. 6, 165–176 (2009).

Ruyssen, I. & Rayp, G. Determinants of intraregional migration in sub-Saharan Africa 1980-2000. J. Dev. Stud. 50, 426–443 (2014).

Backhaus, A., Martinez-Zarzoso, I. & Muris, C. Do climate variations explain bilateral migration? A gravity model analysis. IZA J. Migrat. 4, 3 (2015).

Beine, M. & Parsons, C. Climatic factors as determinants of international migration. Scand. J. Econ. 117, 723–767 (2015).

Coniglio, N. D. & Pesce, G. Climate variability and international migration: an empirical analysis. Environ. Dev. Econ. 20, 434–468 (2015).

Ghimire, R., Ferreira, S. & Dorfman, J. H. Flood-induced displacement and civil conflict. World Dev. 66, 614–628 (2015).

Cai, R., Feng, S., Oppenheimer, M. & Pytlikova, M. Climate variability and international migration: the importance of the agricultural linkage. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 79, 135–151 (2016).

Cattaneo, C. & Peri, G. The migration response to increasing temperatures. J. Dev. Econ. 122, 127–146 (2016).

Maurel, M. & Tuccio, M. Climate instability, urbanisation and international migration. J. Dev. Stud. 52, 735–752 (2016).

Beine, M. & Parsons, C. R. Climatic factors as determinants of international migration: Redux. CESifo Econ. Stud. 63, 386–402 (2017).

Cattaneo, C. & Bosetti, V. Climate-induced international migration and conflicts. CESifo Econ. Stud. 63, 500–528 (2017).

Reuveny, R. & Moore, W. H. Does environmental degradation influence migration? Emigration to developed countries in the late 1980s and 1990s. Soc. Sci. Q. 90, 461–479 (2009).

Damette, O. & Gittard, M. Changement climatique et migrations: les transferts de fonds des migrants comme amortisseurs? Mondes Dev. 179, 85 (2017).

Gröschl, J. & Steinwachs, T. Do natural hazards cause international migration? CESifo Econ. Stud. 63, 445–480 (2017).

Henderson, J. V., Storeygard, A. & Deichmann, U. Has climate change driven urbanization in Africa? J. Dev. Econ. 124, 60–82 (2017).

Mahajan, P. & Yang, D. Taken by Storm: Hurricanes, Migrant Networks, and U.S. Immigration Working Paper 23756 (NBER, 2017); https://doi.org/10.3386/w23756

Marchiori, L., Maystadt, J.-F. & Schumacher, I. Is environmentally induced income variability a driver of human migration? Migr. Dev. 6, 33–59 (2017).

Missirian, A. & Schlenker, W. Asylum applications respond to temperature fluctuations. Science 358, 1610–1614 (2017).

Spencer, N. & Urquhart, M.-A. Hurricane strikes and migration: evidence from storms in central America and the caribbean. Weather Clim. Soc. 10, 569–577 (2018).

Peri, G. & Sasahara, A. The Impact of Global Warming in Rural-Urban Migrations: Evidence from Global Big Data Working Paper 25728 (NBER, 2019).

Wesselbaum, D. & Aburn, A. Gone with the wind: international migration. Glob. Planet. Change 178, 96–109 (2019).

Naudé, W. The determinants of migration from sub-Saharan African countries. J. Afr. Econ. 19, 330–356 (2010).

Alexeev, A., Good, D. H. & Reuveny, R. Weather-Related Disasters and International Migration (Indiana Univ., 2011); http://www.umdcipe.org/conferences/Maastricht/conf_papers/Papers/Effects_of_Natural_Disasters.pdf

Bettin, G. & Nicolli, F. Does Climate Change Foster Emigration from Less Developed Countries? Evidence from Bilateral Data Working Paper 10 (Univ. degli Stud. di Ferrara, 2012).

Brückner, M. Economic growth, size of the agricultural sector, and urbanization in Africa. J. Urban Econ. 71, 26–36 (2012).

Gröschl, J. Climate change and the relocation of population. In Beiträge zur Jahrestagung des Vereins für Soc. 2012 Neue Wege und Herausforderungen für den Arbeitsmarkt des 21. Jahrhunderts - Sess. Migr. II, No. D03-V1, ZBW (Verein für Socialpolitik (German Economic Association), 2012).

Hanson, G. H. & McIntosh, C. Birth rates and border crossings: Latin American migration to the US, Canada, Spain and the UK. Econ. J. 122, 707–726 (2012).

Marchiori, L., Maystadt, J. F. & Schumacher, I. The impact of weather anomalies on migration in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 63, 355–374 (2012).

Drabo, A. & Mbaye, L. M. Natural disasters, migration and education: an empirical analysis in developing countries. Environ. Dev. Econ. 20, 767–796 (2015).

Black, R. et al. The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 3–11 (2011).

Boas, I. et al. Climate migration myths. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 901–903 (2019).

Black, R. et al. Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change. Future Challenges and Opportunities (The Government Office for Science, 2011).

Veroniki, A. A. et al. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 7, 55–79 (2016).

Crespo Cuaresma, J., Fidrmuc, J. & Hake, M. Demand and supply drivers of foreign currency loans in CEECs: a meta-analysis. Econ. Syst. 38, 26–42 (2014).

Hsiang, S. M., Burke, M. & Miguel, E. Quantifying the influence of climate on human conflict. Science 341, 1235367 (2013).

Nawrotzki, R. J. & Bakhtsiyarava, M. International climate migration: evidence for the climate inhibitor mechanism and the agricultural pathway. Popul. Space Place 23, 1–16 (2016).

Beine, M. & Jeusette, L. A Meta-Analysis of the Literature on Climate Change and Migration CREA Discussion Paper Series (Center for Research in Economic Analysis, Univ. Luxembourg, 2018).

Auffhammer, M., Hsiangy, S. M., Schlenker, W. & Sobelz, A. Using weather data and climate model output in economic analyses of climate change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 7, 181–198 (2013).

Hsiang, S. Climate econometrics. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 8, 43–75 (2016).

Hugo, G. Future demographic change and its interactions with migration and climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 21(Suppl.), S21–S33 (2011).

Martin, P. L. & Taylor, J. E. in Development Strategy, Employment and Migration: Insights from Models 43–62 (OECD, 1996).

Feng, S., Krueger, A. B. & Oppenheimer, M. Linkages among climate change, crop yields and Mexico–US cross-border migration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14257–14262 (2010).

Mendelsohn, R. & Dinar, A. Climate change, agriculture, and developing countries: does adaptation matter? World Bank Res. Obs. 14, 277–293 (1999).

Schlenker, W. & Roberts, M. J. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to U.S. crop yields under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15594–15598 (2009).

Schlenker, W. & Lobell, D. B. Robust negative impacts of climate change on African agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 014010 (2010).

Abel, G. J., Brottrager, M., Crespo Cuaresma, J. & Muttarak, R. Climate, conflict and forced migration. Glob. Environ. Change 52, 239–249 (2019).

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Climate and conflict. Annu. Rev. Econ. 7, 577–617 (2015).

Barnett, J. & Adger, W. N. Climate change, human security and violent conflict. Polit. Geogr. 26, 639–655 (2007).

Schlenker, W., Hanemann, W. M. & Fisher, A. C. The impact of global warming on U.S. agriculture: An econometric analysis of optimal growing conditions. Rev. Econ. Stat. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465306775565684 (2006).

Dimitrova, A. & Bora, J. K. Monsoon weather and early childhood health in India. PLoS ONE 15, e0231479 (2020).

Muttarak, R. & Dimitrova, A. Climate change and seasonal floods: potential long-term nutritional consequences for children in Kerala, India. BMJ Glob. Health 4, e001215 (2019).

Deschênes, O. & Greenstone, M. Climate change, mortality, and adaptation: evidence from annual fluctuations in weather in the US. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 3, 152–185 (2011).

Deschenes, O. Temperature, human health, and adaptation: a review of the empirical literature. Energ. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2013.10.013 (2014).

Burgess, R., Deschênes, O., Donaldson, D. & Greenstone, M. Weather, Climate Change and Death in India Working Paper (LSE, 2017).

Zivin, J. G. & Neidell, M. Environment, health, and human capital. J. Econ. Lit. 51, 689–730 (2013).

Gemenne, F. Why the numbers don’t add up: a review of estimates and predictions of people displaced by environmental changes. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 41–49 (2011).

Findley, S. E. Does drought increase migration? A study of migration from rural Mali during the 1983–1985 drought. Int. Migr. Rev. 28, 539 (1994).

Black, R., Arnell, N. W., Adger, W. N., Thomas, D. & Geddes, A. Migration, immobility and displacement outcomes following extreme events. Environ. Sci. Policy 27, S32–S43 (2013).

Bohra-Mishra, P., Oppenheimer, M., Cai, R., Feng, S. & Licker, R. Climate variability and migration in the Philippines. Popul. Environ. 38, 286–308 (2017).

Bardsley, D. K. & Hugo, G. J. Migration and climate change: examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making. Popul. Environ. 32, 238–262 (2010).

Mertz, O., Mbow, C., Reenberg, A. & Diouf, A. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and agricultural adaptation strategies in rural Sahel. Environ. Manage. 43, 804–816 (2009).

Garcia, A. J., Pindolia, D. K., Lopiano, K. K. & Tatem, A. J. Modeling internal migration flows in sub-Saharan Africa using census microdata. Migr. Stud. 3, 89–110 (2015).

Naudé, W. Conflict, Disasters and No Jobs: Reasons for International Migration from sub-Saharan Africa. WIDER Research Paper 85 (United Nations Univ., 2008).

Dell, M., Jones, B. F. & Olken, B. A. What do we learn from the weather? The new climate-economy literature. J. Econ. Lit. 52, 740–798 (2014).

Gemenne, F. & Blocher, J. How can migration serve adaptation to climate change? Challenges to fleshing out a policy ideal. Geogr. J. 183, 336–347 (2017).

Zickgraf, C. Keeping people in place: political factors of (im)mobility and climate change. Soc. Sci. 8, 1–17 (2019).

Ayeb-Karlsson, S. et al. I will not go, I cannot go: cultural and social limitations of disaster preparedness in Asia, Africa, and Oceania. Disasters 43, 752–770 (2019).

Oakes, R. Culture, climate change and mobility decisions in pacific small island developing states. Popul. Environ. 40, 480–503 (2019).

Gharad, B., Chowdhury, S. & Mobarak, A. M. Underinvestment in a profitable technology: the case of seasonal migration in Bangladesh. Econometrica 82, 1671–1748 (2014).

Kniveton, D., Black, R. & Schmidt-Verkerk, K. Migration and climate change: towards an integrated assessment of sensitivity. Environ. Plan. A 43, 431–450 (2011).

Hornbeck, R. The enduring impact of the American Dust Bowl: Short- and long-run adjustments to environmental catastrophe. Am. Econ. Rev. 102, 1477–1507 (2012).

Libecap, G. D. & Steckel, R. H. in The Economics of Climate Change: Adaptations Past and Present (eds Libecap, G. D. & Steckel, R. H.) 1–22 (Univ. Chicago Press, 2011).

Hsiang, S. M. & Narita, D. Adaptation to cyclone risk: evidence from the global cross-section. Clim. Change Econ. 03, 1250011 (2012).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 97–111 (2010).

Hedges, Larry V. & Olkin, I. Statistical Method for Meta-Analysis (Academic Press, 1998).

Lipsey, M. W. & Wilson, D. B. Practical meta-analysis (SAGE Publications, 2001).

Hedges, L. V. & Olkin, I. Vote-counting methods in research synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 88, 359–369 (1980).

Combs, J. G., Ketchen, D. J., Crook, T. R. & Roth, P. L. Assessing cumulative evidence within ‘macro’ research: why meta-analysis should be preferred over vote counting. J. Manage. Stud. 48, 178–197 (2011).

Beine, M., Bertoli, S. & Fernández-Huertas Moraga, J. A practitioners’ guide to gravity models of international migration. World Econ. 39, 496–512 (2016).

Angrist, J. D. & Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics (Princeton Univ. Press, 2009).

Dell, M., Jones, B. F. & Olken, B. A. Temperature shocks and economic growth: evidence from the last half century. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.4.3.66 (2012).

Bohra-Mishra, P., Oppenheimer, M. & Hsiang, S. M. Nonlinear permanent migration response to climatic variations but minimal response to disasters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9780–9785 (2014).

World Development Indicators (The World Bank, 2019).

Marshall, M. G. Major Episodes of Political Violence (MEPV) and Conflict Regions, 1946–2018 (Center for Systemic Peace, 2019).

Sundberg, R. & Melander, E. Introducing the UCDP georeferenced event dataset. J. Peace Res. 50, 523–532 (2013).

Högbladh, S. UCDP GED Codebook Version 19.1 (Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala Univ., 2019).

Harris, I., Jones, P. D., Osborn, T. J. & Lister, D. H. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations—the CRU TS3.10 dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 623–642 (2014).

EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2020); www.emdat.be

Bell, M. et al. Internal migration data around the world: assessing contemporary practice. Popul. Space Place 21, 1–17 (2015).

Bell, M. & Charles-Edwards, E. Cross-National Comparisons of Internal Migration: An Update of Global Patterns and Trends Technical Paper 2013/1 (United Nations, 2013).

Chindarkar, N. Gender and climate change-induced migration: proposing a framework for analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 025601 (2012).

Hoffmann, R., Dimitrova, A., Muttarak, R., Crespo Cuaresma, J. & Peisker, J. A meta-analysis of country level studies on environmental change and migration | replication data and code. Harvard Dataverse, V1 https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HYRXVV (2020).

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019); https://www.r-project.org/

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the papers included in the meta-analysis who kindly shared their data and codes with us. This research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund, grant number Z171-G11.We also thank the IIASA for funding, as well as the National Member Organizations that support the institute. Further funding was provided by the International Climate Initiative (IKI: www.international-climate-initiative.com) and the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research is a member of the Lebniz Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H. and R.M. conceived the project and designed research; A.D., R.H. and R.M. collected and reviewed the literature; J.C.C. helped with statistical techniques and procedures; A.D., R.H. and J.P. collected, compiled and analysed data; J.C.C., A.D., R.H., R.M. and J.P. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Climate Change thanks Cristina Cattaneo, Clark Gray, Jessica Gurevitch and Robert Oakes for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

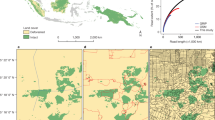

Extended Data Fig. 1 Relationships between environmental hazards and migration for different parts of the world.

Blue lines show climate trends and dark gray bars show population movement variables. Lines for temperature and drought are smoothed moving averages. Temperature and rainfall anomalies are yearly deviations from the long-term average (1901–2016). The standardized precipitation and evapotranspiration index (SPEI) is measured at a 3-month scale. Rapid-onset disasters include climatological, hydrological and meteorological disasters. Sources: a) North Africa, SPEIbase (Beguería et al., Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 2010) and Cai et al. (J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 7922); b) Syria, SPEIbase and UNHCR Refugee Statistics; c) South Asia, CRU TS 3.25 (Harris et al., Int. J. Climatol. 34104) and Cai et al22; d) Central America and Mexico, CRU TS 3.25 and Cai et al22; e) Angola, CRU TS 3.25 and UN World Urbanization Prospects 2018; f) Philippines, EM-DAT and IDMC Global Internal Displacement Database.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Density distributions of standardized effects.

Panel a shows the distribution of (unweighted) standardized effects of all model estimates (k = 1803) across studies (displayed range −1 to +1). Positive effects are highlighted in darker grey. Panel b shows the mean effect distribution on study level (n = 30, between-study variation). Panel c shows the distribution of the deviations of the individual estimates (k = 1803) from the study mean effects (within-study variation).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Differences in sample composition by study cases.

Panel a shows boxplots of the share of countries in the model samples belonging to a specific category of countries. Panel b shows the regional focus of the study models. SSA, Sub Saharan Africa, MENA, Middle East North Africa, LAC, Latin America and the Caribbean, OECD, Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Conflict countries are countries with a recurring conflict for at least five years in the period of 1960 to 2000 (Major Episodes of Political Violence database).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5, Tables 1–16 and references.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffmann, R., Dimitrova, A., Muttarak, R. et al. A meta-analysis of country-level studies on environmental change and migration. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 904–912 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0898-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0898-6

This article is cited by

-

The impact of anthropogenic climate change on pediatric viral diseases

Pediatric Research (2024)

-

Environmental migration? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature

Review of World Economics (2024)

-

A framework to link climate change, food security, and migration: unpacking the agricultural pathway

Population and Environment (2024)

-

Climate (im)mobilities in the Eastern Hindu Kush: The case of Lotkuh Valley, Pakistan

Population and Environment (2024)

-

Beyond borders: exploring the migration-climate change dynamics of Asian migrants to Russian Federation

Letters in Spatial and Resource Sciences (2024)