Abstract

The response of evapotranspiration (ET) to warming is of critical importance to the water and carbon cycle of the boreal biome, a mosaic of land cover types dominated by forests and peatlands. The effect of warming-induced vapour pressure deficit (VPD) increases on boreal ET remains poorly understood because peatlands are not specifically represented as plant functional types in Earth system models. Here we show that peatland ET increases more than forest ET with increasing VPD using observations from 95 eddy covariance tower sites. At high VPD of more than 2 kPa, peatland ET exceeds forest ET by up to 30%. Future (2091–2100) mid-growing season peatland ET is estimated to exceed forest ET by over 20% in about one-third of the boreal biome for RCP4.5 and about two-thirds for RCP8.5. Peatland-specific ET responses to VPD should therefore be included in Earth system models to avoid biases in water and carbon cycle projections.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data for Figs. 1–4 and Extended Data Figs. 1–3 are provided with the paper. Eddy covariance flux tower data used in this study can be accessed through the AmeriFlux (https://ameriflux.lbl.gov/), FLUXNET (https://fluxnet.fluxdata.org/data/fluxnet2015-dataset/), or European Fluxes Database Cluster (http://www.europe-fluxdata.eu/) webpages (see Supplementary Data). Site data that are not accessible through these webpages (see Supplementary Data) are available from the corresponding author on request. Monthly climate data and PET can be accessed through the East Anglia Climate Research Unit webpage (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/cru_ts_4.02/). Most CMIP5 model output is archived and made available through the Earth System Grid Federation (https://esgf.llnl.gov/). CanESM2 model output can be downloaded through the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis (http://climate-modelling.canada.ca/data/cgcm4/CanESM2/index.shtml) and CESM1-CAM5 model output is available through the Climate Data Gateway at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (https://www.earthsystemgrid.org/). Peatland maps are freely available through the Research Data Leeds Repository (http://archive.researchdata.leeds.ac.uk/251/) and on request from the corresponding author. MODIS data can be accessed for all flux tower sites through the Global Subset Tool: MODIS/VIIRS Products (https://modis.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/MODIS/global/subset.pl). The global FLUXCOM land-atmosphere energy flux data product can be accessed through the FLUXCOM webpage (http://www.fluxcom.org/EF-Products/). Global monthly mean LAI climatology can be accessed through the ORNL Distributed Active Archive Center for Biogeochemical Dynamics (https://daac.ornl.gov/VEGETATION/guides/Mean_Seasonal_LAI.html).

Code availability

All MATLAB code used in this study is available through the corresponding author’s GitHub repository72 (https://github.com/manuelhelbig/BWF_Synthesis; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3653056) and is available from the corresponding author on request. The software used to generate all results is MATLAB 2016a.

References

Brandt, J. P., Flannigan, M. D., Maynard, D. G., Thompson, I. D. & Volney, W. J. A. An introduction to Canada’s boreal zone: ecosystem processes, health, sustainability, and environmental issues. Environ. Rev. 21, 207–226 (2013).

Verpoorter, C., Kutser, T., Seekell, D. A. & Tranvik, L. J. A global inventory of lakes based on high-resolution satellite imagery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6396–6402 (2014).

Xu, J., Morris, P. J., Liu, J. & Holden, J. PEATMAP: refining estimates of global peatland distribution based on a meta-analysis. CATENA 160, 134–140 (2018).

Bradshaw, C. J. A. & Warkentin, I. G. Global estimates of boreal forest carbon stocks and flux. Glob. Planet. Change 128, 24–30 (2015).

Le Quéré, C. et al. Global carbon budget 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 2141–2194 (2018).

Goulden, M. L. et al. Sensitivity of boreal forest carbon balance to soil thaw. Science 279, 214–217 (1998).

Kauppi, P. E., Posch, M. & Pirinen, P. Large impacts of climatic warming on growth of boreal forests since 1960. PLoS ONE 9, e111340 (2014).

Turetsky, M. R. et al. Global vulnerability of peatlands to fire and carbon loss. Nat. Geosci. 8, 11–14 (2015).

Koven, C. D. Boreal carbon loss due to poleward shift in low-carbon ecosystems. Nat. Geosci. 6, 452–456 (2013).

Allison, S. D. & Treseder, K. K. Warming and drying suppress microbial activity and carbon cycling in boreal forest soils. Glob. Change Biol. 14, 2898–2909 (2008).

Gentine, P. et al. Coupling between the terrestrial carbon and water cycles—a review. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 083003 (2019).

Woo, M., Thorne, R., Szeto, K. & Yang, D. Streamflow hydrology in the boreal region under the influences of climate and human interference. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 2249–2258 (2008).

Fisher, J. B. et al. The future of evapotranspiration: global requirements for ecosystem functioning, carbon and climate feedbacks, agricultural management, and water resources. Water Resour. Res. 53, 2618–2626 (2017).

Lafleur, P. M. & Rouse, W. R. The influence of surface cover and climate on energy partitioning and evaporation in a subarctic wetland. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 44, 327–347 (1988).

Yuan, W. et al. Increased atmospheric vapor pressure deficit reduces global vegetation growth. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax1396 (2019).

Novick, K. A. et al. The increasing importance of atmospheric demand for ecosystem water and carbon fluxes. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1023–1027 (2016).

Brümmer, C. et al. How climate and vegetation type influence evapotranspiration and water use efficiency in Canadian forest, peatland and grassland ecosystems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 153, 14–30 (2012).

Barr, A. G., Betts, A. K., Black, T. A., McCaughey, J. H. & Smith, C. D. Intercomparison of BOREAS northern and southern study area surface fluxes in 1994. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 33543–33550 (2001).

Massmann, A., Gentine, P. & Lin, C. When does vapor pressure deficit drive or reduce evapotranspiration. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 3305–3320 (2019).

Admiral, S. W. & Lafleur, P. M. Partitioning of latent heat flux at a northern peatland. Aquat. Bot. 86, 107–116 (2007).

Williams, T. G. & Flanagan, L. B. Effect of changes in water content on photosynthesis, transpiration and discrimination against 13CO2 and C18O16O in Pleurozium and Sphagnum. Oecologia 108, 38–46 (1996).

Oren, R. et al. Survey and synthesis of intra- and interspecific variation in stomatal sensitivity to vapour pressure deficit. Plant Cell Environ. 22, 1515–1526 (1999).

Kellner, E. Surface energy fluxes and control of evapotranspiration from a Swedish Sphagnum mire. Agric. For. Meteorol. 110, 101–123 (2001).

Helbig, M. et al. Regional atmospheric cooling and wetting effect of permafrost thaw-induced boreal forest loss. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 4048–4066 (2016).

Chaudhary, N., Miller, P. A. & Smith, B. Modelling past, present and future peatland carbon accumulation across the Pan-Arctic region. Biogeosciences 14, 4023–4044 (2017).

Qiu, C. et al. ORCHIDEE-PEAT (revision 4596), a model for northern peatland CO2, water, and energy fluxes on daily to annual scales. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 497–519 (2018).

Wu, Y., Verseghy, D. L. & Melton, J. R. Integrating peatlands into the coupled canadian land surface scheme (class) v3.6 and the canadian terrestrial ecosystem model (CTEM) v2.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2639–2663 (2016).

Bechtold, M. et al. PEAT-CLSM: a specific treatment of peatland hydrology in the NASA catchment land surface model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2130–2162 (2019).

Poulter, B. et al. Plant functional type mapping for earth system models. Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 993–1010 (2011).

Abramowitz, G., Leuning, R., Clark, M. & Pitman, A. Evaluating the performance of land surface models. J. Clim. 21, 5468–5481 (2008).

Green, J. K. et al. Large influence of soil moisture on long-term terrestrial carbon uptake. Nature 565, 476–479 (2019).

Harris, I., Jones, P. D., Osborn, T. J. & Lister, D. H. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations—the CRU TS3.10 Dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 623–642 (2014).

Yurova, A., Tolstykh, M., Nilsson, M. & Sirin, A. Parameterization of mires in a numerical weather prediction model. Water Resour. Res. 50, 8982–8996 (2014).

Lemordant, L., Gentine, P., Swann, A. S., Cook, B. I. & Scheff, J. Critical impact of vegetation physiology on the continental hydrologic cycle in response to increasing CO2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4093–4098 (2018).

Ewers, B. E., Gower, S. T., Bond-Lamberty, B. & Wang, C. K. Effects of stand age and tree species on canopy transpiration and average stomatal conductance of boreal forests. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 660–678 (2005).

Green, J. K. et al. Regionally strong feedbacks between the atmosphere and terrestrial biosphere. Nat. Geosci. 10, 410–414 (2017).

Trenberth, K. E. Atmospheric moisture recycling: role of advection and local evaporation. J. Clim. 12, 1368–1381 (1999).

Ford, T. W. & Frauenfeld, O. W. Surface–atmosphere moisture interactions in the frozen ground regions of Eurasia. Sci. Rep. 6, 19163 (2016).

Konings, A. G., Katul, G. G. & Porporato, A. The rainfall–no rainfall transition in a coupled land-convective atmosphere system. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L14401 (2010).

Sikma, M. & Vilà-Guerau de Arellano, J. Substantial reductions in cloud cover and moisture transport by dynamic plant responses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 1870–1878 (2019).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320, 1444–1449 (2008).

Teuling, A. J. et al. Contrasting response of European forest and grassland energy exchange to heatwaves. Nat. Geosci. 3, 722–727 (2010).

Alekseychik, P. et al. Surface energy exchange in pristine and managed boreal peatlands. Mires Peat 20, 1–26 (2018).

Zoltai, S. C. & Vitt, D. H. Canadian wetlands: environmental gradients and classification. Vegetatio 118, 131–137 (1995).

Sulman, B. N. et al. CO2 fluxes at northern fens and bogs have opposite responses to inter-annual fluctuations in water table. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L19702 (2010).

Girardin, M. P. et al. Negative impacts of high temperatures on growth of black spruce forests intensify with the anticipated climate warming. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 627–643 (2016).

Clenciala, E., Kucera, J., Ryan, M. G. & Lindroth, A. Water flux in boreal forest during two hydrologically contrasting years; species specific regulation of canopy conductance and transpiration. Ann. Sci. For. 55, 47–61 (1998).

Helbig, M., Humphreys, E. R. & Todd, A. Contrasting temperature sensitivity of CO2 exchange in peatlands of the Hudson Bay Lowlands, Canada. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 124, 2126–2143 (2019).

Fenner, N. & Freeman, C. Drought-induced carbon loss in peatlands. Nat. Geosci. 4, 895–900 (2011).

Charman, D. J. Summer water deficit variability controls on peatland water-table changes: implications for Holocene palaeoclimate reconstructions. The Holocene 17, 217–227 (2007).

Rydin, H. Effect of water level on desiccation of Sphagnum in relation to surrounding Sphagna. Oikos 45, 374–379 (1985).

Waddington, J. M. et al. Hydrological feedbacks in northern peatlands. Ecohydrol. 8, 113–127 (2014).

Waddington, J. M., Kellner, E., Strack, M. & Price, J. S. Differential peat deformation, compressibility, and water storage between peatland microforms: Implications for ecosystem function and development. Water Resour. Res. 46, W07538 (2010).

Nijp, J. J. et al. Including hydrological self-regulating processes in peatland models: Effects on peatmoss drought projections. Sci. Total Environ. 580, 1389–1400 (2017).

Heijmans, M. M. P. D., van der Knaap, Y. A. M., Holmgren, M. & Limpens, J. Persistent versus transient tree encroachment of temperate peat bogs: effects of climate warming and drought events. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 2240–2250 (2013).

Sulman, B. N., Desai, A. R. & Mladenoff, D. J. Modeling soil and biomass carbon responses to declining water table in a wetland-rich landscape. Ecosystems 16, 491–507 (2013).

Carpino, O. A., Berg, A. A., Quinton, W. L. & Adams, J. R. Climate change and permafrost thaw-induced boreal forest loss in northwestern Canada. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 084018 (2018).

Buermann, W., Bikash, P. R., Jung, M., Burn, D. H. & Reichstein, M. Earlier springs decrease peak summer productivity in North American boreal forests. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 024027 (2013).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. BioScience 51, 933–938 (2001).

Hollinger, D. Y. et al. Seasonal patterns and environmental control of carbon dioxide and water vapour exchange in an ecotonal boreal forest. Glob. Change Biol. 5, 891–902 (1999).

Papale, D. et al. Towards a standardized processing of net ecosystem exchange measured with eddy covariance technique: algorithms and uncertainty estimation. Biogeosciences 3, 571–583 (2006).

Reichstein, M. et al. On the separation of net ecosystem exchange into assimilation and ecosystem respiration: review and improved algorithm. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 1424–1439 (2005).

Humphreys, E. R. et al. Summer carbon dioxide and water vapor fluxes across a range of northern peatlands. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 111, G04011 (2006).

Verma, S. B. Aerodynamic Resistances to Transfers of Heat, Mass and Momentum (eds Black, T. A. et al.) Vol. 177, 13–20 (International Association of Hydrological Sciences, 1989); http://hydrologie.org/redbooks/a177/iahs_177_0013.pdf

Medlyn, B. E. et al. Reconciling the optimal and empirical approaches to modelling stomatal conductance. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2134–2144 (2011).

Moore, T. R., Bubier, J. L., Frolking, S. E., Lafleur, P. M. & Roulet, N. T. Plant biomass and production and CO2 exchange in an ombrotrophic bog. J. Ecol. 90, 25–36 (2002).

Kelliher, F. M., Leuning, R., Raupach, M. R. & Schulze, E.-D. Maximum conductances for evaporation from global vegetation types. Agric. For. Meteorol. 73, 1–16 (1995).

Myneni, R., Knyazikhin, Y. & Park, T. MOD15A2H v006: MODIS/Terra Leaf Area Index/FPAR 8-Day L4 Global 500 m SIN Grid (NASA, 2015); https://doi.org/doi:10.5067/MODIS/MOD15A2H.006

Mao, J. & Yan, B. Global Monthly Mean Leaf Area Index Climatology, 1981–2015 (ORNL DAAC, 2019); https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1653

Ficklin, D. L. & Novick, K. A. Historic and projected changes in vapor pressure deficit suggest a continental-scale drying of the United States atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 122, 2061–2079 (2017).

Jung, M. et al. The FLUXCOM ensemble of global land-atmosphere energy fluxes. Sci. Data 6, 74 (2019).

Helbig, M. Analysis of Boreal Peatland and Forest Evapotranspiration (Zenodo, 2020); https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3653056

Acknowledgements

The research published in this paper is part of the project titled Boreal Water Futures, which is funded by the Global Water Futures programme of the Canada First Research Excellence Fund; additional information is available at www.globalwaterfutures.ca. We thank all the eddy covariance flux tower teams for sharing their data and we are grateful to the ESM groups for providing their model output through CMIP5. We thank the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling for leading the CMIP. We acknowledge the research group that made the peatland map freely available and we thank E. Chan (ECCC) for processing the shapefile PEATMAP to a raster map. We are grateful to E. Sahlée and A. Rutgersson for providing lake eddy covariance data to an earlier version of the manuscript, T. Zivkovic and S. Davidson for insightful feedback, and M. Khomik, A. Green, E. Kessel, G. Drewitt, P. Kolari and M. Provenzale for helping with data preparation. I.M. acknowledges funding from ICOS-FINLAND (grant no. 281255), the Finnish Center of Excellence (grant no. 307331) and the EU Horizon 2020 RINGO project (grant no. 730944). A.P. acknowledges funding through the research project no. 18–05–60203-Arktika (RFBR and Government of Krasnoyarsk Territory, Krasnoyarsk Regional Fund of Science) and support for flux tower sites RU-ZOP and RU-ZOB through the Max Planck Society. A.D. and J.T. acknowledge funding from US National Science foundation (grant no. DEB-1440297) and a DOE Ameriflux Network Management Project award to the ChEAS core site cluster. T.A.B., A.G.B. and R.J. acknowledge support received through grants from the Fluxnet Canada ResearchNetwork (2002–2007; NSERC, CFCAS and BIOCAP) and the Canadian Carbon Program (2008–2012; CFCAS) and by an NSERC (Climate Change and Atmospheric Research) grant to the Changing Cold Regions Network (CCRN; 2012–2016) and an NSERC Discovery Grant. H. I. and M. U. acknowledge support by the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability (ArCS) project. J.K. and A.V. acknowledge funding from RFBR project no. 19–04–01234-a. B.A. acknowledges funding through NASA, NSERC, BIOCAP Canada, the Canadian Foundation for Climate and Atmospheric Sciences and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation for flux measurements at CA-MAN and through the Canadian Forest Service, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the FLUXNET-Canada Network (NSERC, the Canadian Foundation for Climate and Atmospheric Sciences (CFCAS) and BIOCAP Canada), the Canadian Carbon Program (CFCAS), Parks Canada, the Program of Energy Research and Development (PERD), and Action Plan 2000 for flux measurements at CA-SF1, CA-SF2 and CA-SF3. M.B.N, M.O.L, M.P. and J.C. gratefully acknowledge funding from the Swedish research infrastructures SITES and ICOS Sweden and research grants from Kempe Foundations, (grant no. SMK-1743); VR (grant no. 2018–03966) and Formas, (grant no. 2016–01289) and M.P. gratefully acknowledges funding from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (grant no. 2015.0047). M.W. and I.F. acknowledge funding by the German Research Foundation (grant no. Wi 2680/2–1) and the European Union (grant no. 36993). B.R. and L.K. acknowledge support by the Cluster of Excellence ‘CliSAP’ (EXC177) of the University of Hamburg, funded by the German Research Foundation. O.S. acknowledges funding by the Canada Research Chairs, Canada Foundation for Innovation Leaders Opportunity Fund, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant Programs. H.I. acknowledges JAMSTEC and IARC/UAF collaboration study (JICS) and Arctic Challenge for Sustainability Project (ArCS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and J.M.W. designed the study. M.H., J.M.W. and J.R.M. developed the methodology. J.M.W., P.A., B.A., M.A., A.G.B., T.A.B., P.D.B., S.K.C, J.Chen, J.Chi, A.R.D., A.D., E.E., T.F., L.B.F., I.F., A.G., S.H., M.H., E.R.H., H.Ikawa, H.Iwata, P.-E.I., R.J., J.K., M.K., L.K., A.Lindroth, T.O., M.O.L., A.Lohila, T.M., I.M., P.M., P.A.M., D.F.N., E.M.N., M.B.N., M.P., R.M.P., R.P., A.P., W.L.Q., N.T.R., D.E.R., B.R.K.R., O.S., I.B.S., P.T., E.-S.T., J.-P.T., J.T., M.U., A.V., M.W., S.W. and V.Z. contributed eddy covariance flux data. M.H. analysed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to data interpretation and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Climate Change thanks Claire Treat and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Anomalies of growing season (May-September) mean daily maximum vapour pressure deficit (VPDGS) for the boreal biome (circles, relative to the mean of 1981–2010).

The solid line shows five-year running mean. VPDGS is derived from the University of East Anglia Climate Research Unit [CRU] TS v4.03 dataset (Methods) and boreal biome grid cells are identified based on ref. 59.

Extended Data Fig. 2

Relationship between observed half-hourly afternoon (15h-18h) evaporative fraction and vapour pressure deficit for forest and peatland sites during the growing season. Shaded areas show standard errors.

Extended Data Fig. 3

Probability density function (PDF, solid lines) of observed growing season (May- September) forest (n = 305 growing seasons) and peatland (n = 122 growing seasons) evapotranspiration. Dashed lines show median growing season evapotranspiration.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

List of eddy covariance flux tower sites used in this study, including metadata for each site.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

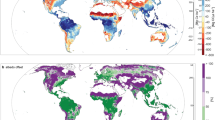

Projected changes in vapour pressure deficit in the boreal biome.

Source Data Fig. 2

Dryness index map and flux tower site locations.

Source Data Fig. 3

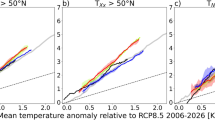

VPD-ET/gs response curve data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Map of current and projected ratios of peatland versus forest ET.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

VPD anomaly data for the boreal biome.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

VPD-evaporative fraction response curve data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Growing season ET data for boreal peatlands and forests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Helbig, M., Waddington, J.M., Alekseychik, P. et al. Increasing contribution of peatlands to boreal evapotranspiration in a warming climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 555–560 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0763-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0763-7

This article is cited by

-

Influence of snowmelt on increasing Arctic river discharge: numerical evaluation

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2024)

-

Wildfire and degradation accelerate northern peatland carbon release

Nature Climate Change (2023)

-

Warming-induced vapor pressure deficit suppression of vegetation growth diminished in northern peatlands

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Peatland groundwater level in the Indonesian maritime continent as an alert for El Niño and moderate positive Indian Ocean dipole events

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Evapotranspiration frequently increases during droughts

Nature Climate Change (2022)