Abstract

Existing literature on climate change beliefs in the US suggests that partisan polarization begets climate change polarization and that the climate beliefs of those on both sides of the partisan divide are firmly held and invariable. Here, we use data from a large panel survey of Oklahoma residents administered quarterly from 2014 through 2018 to challenge this perspective. Contrary to the expectation of rough symmetry in partisan polarization on climate change, we find that partisans on the political right have much more unstable beliefs about climate change than partisans on the left. An important implication is that if climate beliefs are well anchored on the left, but less so on the right, the latter are more susceptible to change. We interpret this to suggest that, despite polarizing elite rhetoric, public beliefs about climate change maintain the potential to shift towards broader acceptance and a perceived need for action.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

M-SISNet data and metadata are available at: http://crcm.ou.edu/epscordata/.

Code availability

R code for the current study is available on GitHub: https://github.com/ripberjt/msisnet.

References

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers. In Global warming of 1.5 °C (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 32 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Saad, L. Americans Concerned as Ever about Climate Change (Gallup, 2019).

Ritchie, E. J. Fact checking the claim of a major shift in climate change opinion. Forbes (30 January 2019).

Hamilton, L. C. Data Snapshot: Public Acceptance of Human-Caused Climate Change is Gradually Rising (Carsey School of Public Policy, University of New Hampshire, 2017).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G. & Fielding, K. S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 622–626 (2016).

McCright, A. M., Charters, M., Dentzman, K. & Dietz, T. Examining the effectiveness of climate change frames in the face of a climate change denial counter-frame. Top. Cogn. Sci. 8, 76–97 (2016).

Kahan, D. Why we are poles apart on climate change. Nature News 488, 255 (2012).

Saad, L. Half in U.S. Are Now Concerned Global Warming Believers (Gallup, 2017).

Leiserowitz, A. et al. Climate Change in the American Mind: October 2017 (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication, 2017).

Kahn, M. E. & Kotchen, M. J. Business cycle effects on concern about climate change: the chilling effects of recession. Clim. Change Econ. 2, 257–273 (2011).

Mildenberger, M. & Leiserowitz, A. Public opinion on climate change: is there an economy–environment tradeoff? Environ. Pol. 26, 801–824 (2017).

Dunlap, R. E., McCright, A. M. & Yarosh, J. H. The political divide on climate change: partisan polarization widens in the US. Environ. Sci. Pol. Sustain. Dev. 58, 4–23 (2016).

Carmichael, J. T. & Brulle, R. J. Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: an integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001–2013. Environ. Pol. 26, 232–252 (2017).

Tesler, M. Elite domination of public doubts about climate change (not evolution). Pol. Commun. 35, 306–326 (2018).

Howe, P. D., Marlon, J. R., Mildenberger, M. & Shield, B. S. How will climate change shape climate opinion? Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 113001 (2019).

Moore, F. C., Obradovich, N., Lehner, F. & Baylis, P. Rapidly declining remarkability of temperature anomalies may obscure public perception of climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 4905–4910 (2019).

Ripberger, J. T. et al. Bayesian versus politically motivated reasoning in human perception of climate anomalies. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 114004 (2017).

McCright, A. M., Marquart-Pyatt, S. T., Shwom, R. L., Brechin, S. R. & Allen, S. Ideology, capitalism, and climate: explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 21, 180–189 (2016).

Krehbiel, K. Pivotal Politics: A Theory of US Lawmaking (University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Deeg, K., Lyon, E., Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., & Marlon, J. Who is changing their mind about global warming and why? (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2019).

Smith, T. W. Recalling attitudes: an analysis of retrospective questions on the 1982 GSS. Public Opin. Quart. 48, 639–649 (1984).

Dex, S. The reliability of recall data: a literature review. Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 49, 58–89 (1995).

Palm, R., Lewis, G. B. & Feng, B. What causes people to change their opinion about climate change? Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 107, 883–896 (2017).

Jenkins-Smith, H. et al. The Oklahoma meso-scale integrated socio-geographic network: a technical overview. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 34, 2431–2441 (2017).

Howe, P., Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J. & Leiserowitz, A. Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 596–603 (2015).

Burstein, P. The impact of public opinion on public policy: a review and an agenda. Pol. Res. Quart. 56, 29–40 (2003).

Converse, P. E. Changing conceptions of public opinion in the political process. Public Opin. Quart. 51, S12–S24 (1987).

Zaller, J. R. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992).

Bassili, J. N. & Fletcher, J. F. Response-time measurement in survey research a method for CATI and a new look at nonattitudes. Public Opin. Quart. 55, 331–346 (1991).

Yan, T. & Tourangeau, R. Fast times and easy questions: the effects of age, experience and question complexity on web survey response times. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 22, 51–68 (2008).

Krosnick, J. A. Response strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitude measures in surveys. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 5, 213–236 (1991).

Converse, P. E. in Handbook of Political Science (eds Greenstein, F. I. & Polsby, N. W.) 75–170 (Addison-Wesley, 1975).

Zaller, J. & Feldman, S. A simple theory of the survey response: answering questions versus revealing preferences. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 36, 579–616 (1992).

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J. & Rasinski, K. The Psychology of Survey Response (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000).

Hoffman, A. J. The growing climate divide. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 195–196 (2011).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociol. Quart. 52, 155–194 (2011).

Hamilton, L. C., Hartter, J., Lemcke-Stampone, M., Moore, D. W. & Safford, T. G. Tracking public beliefs about anthropogenic climate change. PLoS ONE 10, e0138208 (2015).

Kahan, D., Jenkins‐Smith, H. & Braman, D. Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J. Risk Res. 14, 147–174 (2011).

Kahan, D. M. et al. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 732–735 (2012).

Grant, J. On climate change, John Kasich marches to a different beat. The Allegheny Front (11 March 2016).

Gladwell, M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make A Big Difference (Abacus, 2006).

Centola, D., Becker, J., Brackbill, D. & Baronchelli, A. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention. Science 360, 1116–1119 (2018).

Sunstein, C. R. How Change Happens (Michigan Institute of Technology Press, 2019).

Gardina, J. The tipping point: legal epidemics, constitutional doctrine, and the defense of marriage act. Vermont Law Rev. 34, 291 (2009).

Lohmann, S. The dynamics of informational cascades: the Monday demonstrations in Leipzig, East Germany, 1989–91. World Pol. 47, 42–101 (1994).

Gelman, A. Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Stats Medicine 27, 2865–2873 (2008).

Imai, K., King, G., & Lau, O. Zelig: Everyone’s Statistical Software v.3 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study is based on work supported by the National Science foundation under grant no. OIA-1301789. The authors thank M. Henderson, A. Goodin and the University of Oklahoma Public Opinion Learning Laboratory (OU POLL) for their help with survey implementation and data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study. H.J-S., C.S., J.R., and N.C. contributed to data collection. J.R., H.J-S., and D.C. conducted the data analysis. All authors contributed to writing and editing the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Climate Change thanks Lawrence Hamilton and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

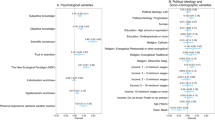

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of predicted certainty of climate change beliefs of Oklahoma panelists with a cross-section of US adults.

Points indicate conditional mean estimates from linear regression models with covariates in the models set to their average values. Panel (a) shows these estimates by political ideology and (b) shows them by political party. N-sizes are 1,353 for Oklahoma and 1,673 for the US in (a) and 1,353 for Oklahoma and 1,771 for the US in (b). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Distribution of variation in panelist’s beliefs about climate change by wave count.

Wave count indicates the number of quarterly surveys panelists completed, ranging from 2+ surveys (n=2,115) to all 16 surveys (n=614).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Prediction of variation in panelist’s beliefs about climate change by wave count.

Points indicate coefficient estimates from models comparable the one shown in Table 1, but the samples used vary by the number of quarterly surveys panelists completed, ranging from 2+ surveys (n=2,097) to all 16 surveys (n=612). Coefficients shown in panel (a) correspond to column 1 in Table 1; (b) corresponds to column 2 in Table 1; and c, corresponds to column 3 in Table 1. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Distribution of variation in panelist’s beliefs about climate change.

Proportion of panelists (n = 1,380) at each value of within-subject root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD). Percentages indicate the percent of panelists in each bin marked with a red dotted line.

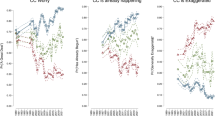

Extended Data Fig. 5 Time series trends in sample panelist’s beliefs about climate change.

Belief in climate change for random samples of 25 panelists with (a) stable beliefs (RMSSD < 1); 18% of the full sample; (b) somewhat stable beliefs (1 < RMSSD < 2); 22% of the full sample; (c) somewhat unstable beliefs (2 < RMSSD < 3); 12% of the full sample; and (d) unstable beliefs (RMSSD> 3); 48% of the full sample.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Influence of ideology and partisanship on variation in climate change beliefs.

Conditional mean estimates of within-subject RMSSD for (a) political ideology and (b) political party when the covariates in the linear regression models are set to their average values. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. N-sizes are 1,374 for (a) and 1,353 for (b).

Extended Data Fig. 7 The Effects of Salience and Cues from Scientists on variation in climate change beliefs.

Points indicate mean estimates of within-subject RMSSD for (a) issue salience and (b) cues from scientists for panelists identifying as Democrat. For (a), n size for Democrats is 330 and for Republicans is 459. For (b), n size for Democrats is 331 and for Republicans is 464 . Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Influence of ideology and partisanship on variation in beliefs that climate change is or is not occurring.

Conditional estimates of the probability of at least one change in beliefs for (a) political ideology and (b) political party when the covariates in the linear regression models are set to their average values. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. N-sizes are 1,374 for (a) and 1,353 for (b).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Influence of the 2016 US election on variation in climate change beliefs.

Points indicate mean estimates of within-subject standard deviation based on (a) political ideology and (b) political party before the 2016 US election (n=1,368) and after the 2016 US election (n=1,345). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Influence of ideology and partisanship on survey variability.

Conditional mean estimates of survey variability for (a) political ideology and (b) political party when the covariates in the linear regression models are set to their average values. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. N-sizes are 1,374 for (a) and 1,353 for (b).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 1–5 and Supplementary Note 1.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jenkins-Smith, H.C., Ripberger, J.T., Silva, C.L. et al. Partisan asymmetry in temporal stability of climate change beliefs. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 322–328 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0719-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0719-y

This article is cited by

-

Financial constraints and short-term planning are linked to flood risk adaptation gaps in US cities

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Increase in concerns about climate change following climate strikes and civil disobedience in Germany

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Multidimensional partisanship shapes climate policy support and behaviours

Nature Climate Change (2023)

-

Hedonism as a motive for information search: biased information-seeking leads to biased beliefs

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Respondents with more extreme views show moderation of opinions in multi-year surveys in the USA and the Netherlands

Communications Psychology (2023)