Abstract

The effects of education on people’s climate change beliefs vary as a function of political ideology: for those on the political left, education is related to pro-climate change beliefs, whereas for those on the political right, these effects are weak or negative. This phenomenon has been examined mainly in the US, where climate change has become a highly politicized issue; however, climate change is less politicized in other contexts. Here we analyse the effects of education and political ideology across 64 countries and show that education has positive effects on pro-climate change beliefs at low and mid-levels of development. At higher levels of development, right-wing ideology attenuates (but does not reverse) the positive effects of education. These analyses extend previous findings by systematically investigating the between-country variation in the relationship between education, ideology and climate change beliefs. The current findings suggest that US-centric theories on the topic should not be generally applied to other contexts uncritically.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Country-level data HDI are available at http://hdr.undp.org/en/data.

Per capita carbon emission data are available at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Type/TABLE/preview/on.

European Social Survey data are available at https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=8.

World Value Survey data are available at http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp.

Data from Hornsey et al.27 are available at https://osf.io/qzxv9/?view_only=852910a2c08c42018edf84a0b556aa14.

Code availability

The analysis code is available at https://osf.io/6ebna/.

References

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G. & Fielding, K. S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 622–626 (2016).

McCright, A. M., Marquart-Pyatt, S. T., Shwom, R. L., Brechin, S. R. & Allen, S. Ideology, capitalism, and climate: explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 21, 180–189 (2016).

Driscoll, D. Assessing sociodemographic predictors of climate change concern, 1994–2016. Soc. Sci. Q. 100, 1699–1708 (2019).

Lewandowsky, S. & Oberauer, K. Motivated rejection of science. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 25, 217–222 (2016).

Ballew, M. T., Pearson, A. R., Goldberg, M. H., Rosenthal, S. A. & Leiserowitz, A. Does socioeconomic status moderate the political divide on climate change? The roles of education, income, and individualism. Glob. Environ. Change 60, 102024 (2020).

Drummond, C. & Fischhoff, B. Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9587–9592 (2017).

Ehret, P. J., Sparks, A. C. & Sherman, D. K. Support for environmental protection: an integration of ideological-consistency and information-deficit models. Environ. Polit. 26, 253–277 (2017).

Hamilton, L. C. Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Climatic Change 104, 231–242 (2011).

Hamilton, L. C., Hartter, J., Lemcke-Stampone, M., Moore, D. W. & Safford, T. G. Tracking public beliefs about anthropogenic climate change. PLoS ONE 10, e0138208 (2015).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the american public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociol. Q. 52, 155–194 (2011).

Kahan, D. M. Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 8, 407–424 (2013).

Kahan, D. M. et al. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 732–735 (2012).

Zaller, J. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992).

Brulle, R. J., Carmichael, J. & Jenkins, J. C. Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010. Climatic Change 114, 169–188 (2012).

Guilbeault, D., Becker, J. & Centola, D. Social learning and partisan bias in the interpretation of climate trends. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9714–9719 (2018).

McPhetres, J. & Pennycook, G. Science beliefs, political ideology, and cognitive sophistication. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/ad9v7 (2019).

Jenkins-Smith, H. C. et al. Partisan asymmetry in temporal stability of climate change beliefs. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 322–328 (2020).

Unsworth, K. L. & Fielding, K. S. It’s political: how the salience of one’s political identity changes climate change beliefs and policy support. Glob. Environ. Change 27, 131–137 (2014).

Painter, J. & Ashe, T. Cross-national comparison of the presence of climate scepticism in the print media in six countries, 2007–10. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 044005 (2012).

Birch, S. Political polarization and environmental attitudes: a cross-national analysis. Environ. Polit. 29, 1–22 (2019).

McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E. & Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Environ. Polit. 25, 338–358 (2016).

Collomb, J.-D. The ideology of climate change denial in the united states. Eur. J. Am. Stud. https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.10305 (2014).

DeBardeleben, J. in Shades of Green: Environmental Attitudes in Canada and Around the World (eds Pammett, J. & Frizzel, A.) 147–168 (Carleton Univ. Press, 1997).

Haller, M. & Hadler, M. Dispositions to act in favor of the environment: fatalism and readiness to make sacrifices in a cross-national perspective. Sociol. Forum 23, 281–311 (2008).

Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. Environmental concerns in cross-national context: how do mass publics in Central and Eastern europe compare with other regions of the world? Sociol. Časopis Czech Sociol. Rev. 48, 441–446 (2012).

Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., Steg, L., Böhm, G. & Fisher, S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: a cross-European analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 55, 25–35 (2019).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A. & Fielding, K. S. Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 614–620 (2018).

Kim, S. Y. & Wolinsky-Nahmias, Y. Cross-national public opinion on climate change: the effects of affluence and vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Polit. 14, 79–106 (2014).

Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C.-Y. & Leiserowitz, A. A. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1014–1020 (2015).

Givens, J. E. & Jorgenson, A. K. The effects of affluence, economic development, and environmental degradation on environmental concern: a multilevel analysis. Organ. Environ. 24, 74–91 (2011).

Dunlap, R. E. & Mertig, A. G. Global environmental concern: an anomaly for postmaterialism. Soc. Sci. Q. 78, 21–29 (1997).

Kvaløy, B., Finseraas, H. & Listhaug, O. The publics’ concern for global warming: a cross-national study of 47 countries. J. Peace Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343311425841 (2012).

Franzen, A. & Vogl, D. Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: a comparative analysis of 33 countries. Glob. Environ. Change 23, 1001–1008 (2013).

Dunlap, R. E. & York, R. The globalization of environmental concern and the limits of the postmaterialist values explanation: evidence from four multinational surveys. Sociol. Q. 49, 529–563 (2008).

Guha, R. Environmentalism: A Global History (Pearson, 1999).

Inglehart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton Univ. Press, 1997).

Dunlap, R. E. Clarifying anti-reflexivity: conservative opposition to impact science and scientific evidence. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 021001 (2014).

McCright, A. M., Dentzman, K., Charters, M. & Dietz, T. The influence of political ideology on trust in science. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 044029 (2013).

European Social Survey Round 8 Data (European Social Survey, 2016); https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS8-2016

European Values Study 1981–2008, Longitudinal Data File. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne, Germany, ZA4804 Data File Version 1.0.0 (2011-04-30) (2011); https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13486

WVS. World Values Survey: All Rounds - Country-Pooled Datafile Version V1.2 (JD Systems Institute, 2015); http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp

Kossowska, M. & Van Hiel, A. The relationship between need for closure and conservative beliefs in Western and Eastern Europe. Polit. Psychol. 24, 501–518 (2003).

Mölder, M. The validity of the RILE left–right index as a measure of party policy. Part. Polit. 22, 37–48 (2016).

Nawrotzki, R. J. The politics of environmental concern: a cross-national analysis. Organ. Environ. 25, 286–307 (2012).

Campbell, T. H. & Kay, A. C. Solution aversion: on the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107, 809–824 (2014).

Kahan, D. M. Climate-science communication and the measurement problem. Polit. Psychol. 36, 1–43 (2015).

Tucker, M. Carbon dioxide emissions and global GDP. Ecol. Econ. 15, 215–223 (1995).

Steinberger, J. K. & Roberts, J. T. From constraint to sufficiency: the decoupling of energy and carbon from human needs, 1975–2005. Ecol. Econ. 70, 425–433 (2010).

Inglehart, R. Public support for environmental protection: objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 28, 57–72 (1995).

Cornelis, I., Hiel, A. V., Roets, A. & Kossowska, M. Age differences in conservatism: evidence on the mediating effects of personality and cognitive style. J. Pers. 77, 51–88 (2009).

Vollebergh, Wa. M., Iedema, J. & Meuss, W. The emerging gender gap: cultural and economic conservatism in the Netherlands 1970–1992. Polit. Psychol. 20, 291–321 (1999).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. Cool dudes: the denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 1163–1172 (2011).

Reinhart, R. Global warming age gap: younger Americans most worried. Gallup (11 May 2018); https://news.gallup.com/poll/234314/global-warming-age-gap-younger-americans-worried.aspx

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R (RStudio, 2019).

Wickham, H. & Miller, E. Haven: Import and Export ‘SPSS’, ‘Stata’ and ‘SAS’ Files. R package version 2.1.1 (RStudio, 2019).

Wickham, H. tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the ‘Tidyverse’ (RStudio, 2019).

Wickham, H. scales: Scale Functions for Visualization. R package version 1.0.0 (RStudio, 2020).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmertest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13 (2017).

Nash, J. C. & Varadhan, R. Unifying optimization algorithms to aid software system users: optimx for R. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v043.i09 (2011).

Nash, J. C. On best practice optimization methods in R. J. Stat. Softw. 60, 1–14 (2014).

Lenth, R. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (2019).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. Visualizing fit and lack of fit in complex regression models with predictor effect plots and partial residuals. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v087.i09 (2018).

Hothorn, T., Bretz, F. & Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 50, 346–363 (2008).

Lüdecke, D. ggeffects: Tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 772 (2018).

Lüdecke, D. sjPlot—Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science (2018); https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1308157

Human Development Report 2016: Human Development for Everyone (United Nations Development Programme, 2016); http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf

Human Development Report 2005. International Cooperation at a Crossroads: Aid, Trade and Security in an Unequal World (United Nations Development Programme, 2005); http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/266/hdr05_complete.pdf

World Development Indicators (The World Bank, accessed 27 February 2020); https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Type/TABLE/preview/on#

Malka, A., Soto, C. J., Inzlicht, M. & Lelkes, Y. Do needs for security and certainty predict cultural and economic conservatism? A cross-national analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106, 1031–1051 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by RIKSBANKENS JUBILEUMSFOND (grant no. M18-0310:1; 2019–2024). We thank T. Lindholm for providing comments to an early version of the paper and A. Mansure for helping to prepare the figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C. and M.K. contributed to the design of the study. G.C. conducted analyses. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Climate Change thanks Matthew Ballew, Robin Bayes and Matthew Hornsey for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

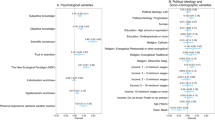

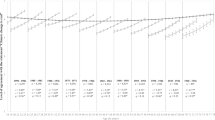

Extended Data Fig. 1 Per-country effects of left-right identification, education, and their interaction on climate change awareness (2016 European Social Survey data).

We first display the effects for the English-speaking countries and then the rest of the European countries by their HDI. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Per-country effects of education for the political left and right on climate change awareness (2016 European Social Survey data).

The order of the countries reflects the charts with the coefficients presented in Extended Data Fig. 1. Grey shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals. CC = climate change.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Per-country effects of left-right identification, education, and their interaction on the beliefs that climate change is human-caused (2016 European Social Survey data).

We first display the effects for the English-speaking countries and then the rest of the European countries by their HDI. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Per-country effects of education for the political left and right on the beliefs that climate change is human-caused (2016 European Social Survey data).

The order of the countries reflects the charts with the coefficients presented in Extended Data Fig. 3. Grey shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals. CC = climate change.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Per-country effects of the left-right identification, education, and their interaction on the beliefs that climate change is human-caused (data from Hornsey et al., 2018).

We first display the effects for the US and English-speaking countries, then for the European and the countries from other continents by their HDI. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Per-country effects of education for the political left and right on the belief that climate change is human-caused (data from Hornsey et al., 2018).

The order of the countries reflects the charts with the coefficients presented in Extended Data Fig. 5. Grey shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals. CC=climate change.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Per-country effects of left-right identification, education, and their interaction on the perception of climate change seriousness (2005–2009 World Value Survey data).

We first display the effects for the US and English-speaking countries, then for the European countries and the countries from other continents by their HDI. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Per-country effects of education for the political left and right on the perception of climate change seriousness (2005–2009 World Value Survey data).

The order of the countries reflects the charts with the coefficients presented in Extended Data Fig. 7. Grey shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals. CC=climate change.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Per-country effects of left-right identification, education, and their interaction on climate change policy support (2016 European Social Survey data).

We first display the effects for the English-speaking countries and then the rest of the European countries by their HDI. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Per-country effects of education for the political left and right on climate change policy support (2016 European Social Survey data).

The order of the countries reflects the charts with the coefficients presented in Extended Data Fig. 9. Grey shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals. CC=climate change.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–25 and Figs. 1–36.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Czarnek, G., Kossowska, M. & Szwed, P. Right-wing ideology reduces the effects of education on climate change beliefs in more developed countries. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 9–13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00930-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00930-6

This article is cited by

-

Financial constraints and short-term planning are linked to flood risk adaptation gaps in US cities

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Comparative analysis of Australian climate change and COVID-19 vaccine audience segments shows climate skeptics can be vaccine enthusiasts

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Global warming vs. climate change frames: revisiting framing effects based on new experimental evidence collected in 30 European countries

Climatic Change (2023)

-

Ideology, scientific literacy, and climate change: the case of Spain

Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences (2023)

-

Drought Exposure and Accuracy: Motivated Reasoning in Climate Change Beliefs

Environmental and Resource Economics (2023)