Abstract

The gap between actual carbon prices and those required to achieve ambitious climate change mitigation could be closed by enhancing the public acceptability of carbon pricing through appropriate use of the revenues raised. In this Perspective, we synthesize findings regarding the optimal use of carbon revenues from both traditional economic analyses and studies in behavioural and political science that are focused on public acceptability. We then compare real-world carbon pricing regimes with theoretical insights on distributional fairness, revenue salience, political trust and policy stability. We argue that traditional economic lessons on efficiency and equity are subsidiary to the primary challenge of garnering greater political acceptability and make recommendations for enhancing political support through appropriate revenue uses in different economic and political circumstances.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2018 (World Bank, Ecofys & Vivid Economics, 2018).

Carbon Pricing Watch 2017 (World Bank & Ecofys, 2017); https://go.nature.com/2KnGk8t

Stiglitz, J. E. & Stern, N. Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices (World Bank, 2017).

Benson, J. E. Massachusetts Bill H.1726. An Act to Promote Green Infrastructure, Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and Create Jobs (General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2017); https://malegislature.gov/Bills/190/H1726

California’s 2017 Climate Change Scoping Plan (California Air Resources Board, 2017).

US Republican idea for tax on carbon makes climate sense. Nature 542, 271–272 (2017).

Baranzini, A., Goldemberg, J. & Speck, S. A future for carbon taxes. Ecol. Econ. 32, 395–412 (2000).

Drews, S. & van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. What explains public support for climate policies? A review of empirical and experimental studies. Clim. Policy 16, 855–876 (2016).

Bowen, A. Carbon Pricing: How Best to Use the Revenue? (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 2015).

Engström, G. & Gars, J. Optimal taxation in the macroeconomics of climate change. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 7, 127–150 (2015).

Aldy, J. E. & Stavins, R. N. The promise and problems of pricing carbon: theory and experience. J. Environ. Dev. 21, 152–180 (2012).

Aldy, J. E. & Pizer, W. A. The competitiveness impacts of climate change mitigation policies. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2, 565–595 (2015).

Jenkins, J. D. Political economy constraints on carbon pricing policies: What are the implications for economic efficiency, environmental efficacy, and climate policy design? Energy Policy 69, 467–477 (2014).

Impacts of Carbon Prices on Indicators of Competitiveness: A Review of Empirical Findings (OECD, 2015).

Carbon Pricing, Competitiveness, and Carbon Leakage: Theory, Evidence and Policy Design (World Bank, 2015).

Martin, R., Muûls, M., Laure, L. B. & Wagner, U. J. Industry compensation under relocation risk: a firm-level analysis of the EU emissions trading scheme. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 2482–2508 (2014).

Svendsen, G. T., Daugbjerg, C., Hjollund, L. & Pedersen, A. B. Consumers, industrialists and the political economy of green taxation: CO2 taxation in OECD. Energy Policy 29, 489–497 (2001).

Jakob, M., Steckel, J. C. & Edenhofer, O. Consumption- versus production-based emission policies. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 6, 297–318 (2014).

Andersen, M. S. & Ekins, P. (eds). Carbon-Energy Taxation: Lessons from Europe (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2009).

Goulder, L. H. Climate change policy’s interactions with the tax system. Energy Econ. 40, S3–S11 (2013).

Klenert, D. & Mattauch, L. How to make a carbon tax reform progressive: The role of subsistence consumption. Econ. Lett. 138, 100–103 (2016).

Bennear, L. S. & Stavins, R. N. Second-best theory and the use of multiple policy instruments. Environ. Resour. Econ. 37, 111–129 (2007).

Combet, E. Fiscalité Carbone et Progrès Social (Carbon Taxation and Social Progress). PhD thesis, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (2013).

Mirrlees, J. A. An exploration in the theory of optimal taxation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 38, 175–208 (1971).

Aigner, R. Environmental taxation and redistribution concerns. Finanz. Public Financ. Anal. 70, 249–277 (2014).

Cremer, H., Gahvari, F. & Ladoux, N. Environmental tax design with endogenous earning abilities (with applications to France). J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 59, 82–93 (2010).

Cremer, H. & Gahvari, F. Second-best taxation of emissions and polluting goods. J. Public Econ. 80, 169–197 (2001).

Jacobs, B. & de Mooij, R. A. Pigou meets Mirrlees: On the irrelevance of tax distortions for the second-best Pigouvian tax. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 71, 90–108 (2015).

Klenert, D., Schwerhoff, G., Edenhofer, O. & Mattauch, L. Environmental taxation, inequality and engel’s law: the double dividend of redistribution. Environ. Resour. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-016-0070-y (2016).

Drèze, J. & Stern, N. Policy reform, shadow prices, and market prices. J. Public Econ. 42, 1–45 (1990).

Siegmeier, J. et al. The fiscal benefits of stringent climate change mitigation: an overview. Clim. Policy 18, 352–367 (2017).

Carbone, J. C., Morgenstern, R. D., Williams R. III & Burtraw, D. Deficit Reduction and Carbon Taxes: Budgetary, Economic, and Distributional Impacts (Resources for the Future, 2013).

Combet, E. & Méjean, A. The Equity and Efficiency Trade-off of Carbon Tax Revenue Recycling: A Reexamination (CIRED, 2017); https://go.nature.com/2MolwuY

Goulder, L. H. & Hafstead, M. A. C. Tax Reform and Environmental Policy: Options for Recycling Revenue from a Tax on Carbon Dioxide Discussion Paper 13-31 (Resources for the Future, 2013).

Mckibbin, W. J., Morris, A. C., Wilcoxen, P. J. & Cai, Y. The Potential Role of a Carbon Tax in U. S. Fiscal Reform (Brookings Climate and Energy Economics, 2012).

Rausch, S., Metcalf, G. E. & Reilly, J. M. Distributional impacts of carbon pricing: a general equilibrium approach with micro-data for households. Energy Econ. 33, S22–S33 (2011).

Williams, R. C. I., Gordon, H., Burtraw, D., Carbone, J. C. & Morgenstern, R. D. The Initial Incidence of a Carbon Tax across US States. Natl Tax. J. 68, 195–214 (2015).

Rausch, S. & Reilly, J. Carbon taxes, deficits, and energy policy interactions. Natl Tax. J. 68, 157–178 (2015).

Gonand, F. The carbon tax, ageing and pension deficits. Environ. Model. Assess. 21, 307–322 (2016).

Camerer, C., Loewenstein, G. & Rabin, M. in Advances in Behavioral Economics (eds Camerer, C., Loewenstein, G. & Rabin, M.) 3–51 (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ, 2004).

Chetty, R., Looney, A. & Kroft, K. Salience and taxation: theory and evidence. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 1145–1177 (2009).

DellaVigna, S. Psychology and economics: evidence from the field. J. Econ. Lit. 47, 315–372 (2009).

Shogren, J. F. & Taylor, L. O. On behavioral-environmental economics. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2, 26–44 (2008).

Allcott, H., Mullainathan, S. & Taubinsky, D. Energy policy with externalities and internalities. J. Public Econ. 112, 72–88 (2014).

Alberini, A., Bigano, A., Šcasný, M., & Zverinoá, I. Preferences for energy efficiency vs. renewables: what is the willingness to pay to reduce CO2 emissions? Ecol. Econ. 144, 171–185 (2016).

Ziegler, A. Political orientation, environmental values, and climate change beliefs and attitudes: an empirical cross country analysis. Energy Econ. 63, 144–153 (2017).

Campbell, T. H. & Kay, A. C. Solution aversion: on the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107, 809–824 (2014).

Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H. & Braman, D. Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J. Risk Res. 14, 147–174 (2011).

Cherry, T. L., Kallbekken, S. & Kroll, S. Accepting market failure: cultural worldviews and the opposition to corrective environmental policies. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 85, 193–204 (2017).

Kallbekken, S., Kroll, S. & Cherry, T. L. Do you not like Pigou, or do you not understand him? Tax aversion and revenue recycling in the lab. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 62, 53–64 (2011).

Bristow, A. L., Wardman, M., Zanni, A. M. & Chintakayala, P. K. Public acceptability of personal carbon trading and carbon tax. Ecol. Econ. 69, 1824–1837 (2010).

Baranzini, A., Caliskan, M. & Carattini, S. Economic Prescriptions and Public Responses to Climate Policy HES-SO/HEG-GE/C-14/3/1 (Haute École de Gestion de Genève, 2014).

Baranzini, A. & Carattini, S. Effectiveness, earmarking and labeling: testing the acceptability of carbon taxes with survey data. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 19, 197–227 (2017).

Hsu, S. L., Walters, J. & Purgas, A. Pollution tax heuristics: an empirical study of willingness to pay higher gasoline taxes. Energy Policy 36, 3612–3619 (2008).

Kallbekken, S. & Aasen, M. The demand for earmarking: results from a focus group study. Ecol. Econ. 69, 2183–2190 (2010).

Kotchen, M. J., Turk, Z. M. & Leiserowitz, A. A. Public willingness to pay for a US carbon tax and preferences for spending the revenue. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 094012 (2017).

Steg, L., Dreijerink, L. & Abrahamse, W. Why are energy policies acceptable and effective? Environ. Behav. 38, 92–111 (2006).

Gevrek, Z. E. & Uyduranoglu, A. Public preferences for carbon tax attributes. Ecol. Econ. 118, 186–197 (2015).

Carattini, S., Baranzini, A., Thalmann, P., Varone, F. & Vöhringer, F. Green taxes in a post-Paris world: are millions of nays inevitable? Environ. Resour. Econ. 68, 97–128 (2017).

Carattini, S., Carvalho, M. & Fankhauser, S. How to Make Carbon Taxes More Acceptable (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2017).

Atansah, P., Khandan, M., Moss, T., Mukherjee, A. & Richmond, J. When Do Subsidy Reforms Stick? Lessons from Iran, Nigeria, and India (Center for Global Development, 2017); https://go.nature.com/2MWXmIZ

Rivers, N. & Schaufele, B. Salience of carbon taxes in the gasoline market. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 74, 23–36 (2015).

Davis, L. W. & Kilian, L. Estimating the effect of a gasoline tax on carbon emissions. J. Appl. Econ. 26, 1187–1214 (2011).

Baranzini, A. & Weber, S. Elasticities of gasoline demand in Switzerland. Energy Policy 63, 674–680 (2013).

Li, S., Linn, J. & Muehlegger, E. Gasoline taxes and consumer behavior. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 6, 302–342 (2014).

Edenhofer, O., Knopf, B., Bak, C. & Bhattacharya, A. Aligning climate policy with finance ministers’ G20 agenda. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 463–465 (2017).

Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth (OECD, 2017).

Sage, D. & Diamond, P. Europe’s New Social Reality: The Case Against Universal Basic Income (Policy Network, 2017); https://repository.edgehill.ac.uk/8738

Rafaty, R. Perceptions of corruption, political distrust, and the weakening of climate policies. Glob. Environ. Polit. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3175064 (2018).

Hammar, H. & Jagers, S. C. Can trust in politicians explain individuals’ support for climate policy? The case of CO2 tax. Clim. Policy 5, 613–625 (2006).

Levi, M. & Stoker, L. Political trust and trustworthiness. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 3, 475–507 (2000).

Rothstein, B. & Uslaner, E. M. All for all: equality, corruption, and social trust. World Polit. 58, 41–72 (2005).

Hourcade, J. C. & Combet, E. Carbon Taxation and Climate Finance: A Social Contract for Our Times [in French] (Les Petits Matins, Institut Veblen, Paris, 2017).

Agell, J., Englund, P. & Södersten, J. A. N. Tax reform of the century: the Swedish experiment. Natl Tax. J. 49, 1–22 (1996).

Sterner, T. Environmental Tax Reform in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 5, 135–163 (1995).

Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Harvard Univ. Press, Cabridge, USA, 1965). https://go.nature.com/2lBMQL2

Aldy, J. E. Mobilizing political action on behalf of future generations. Future Child. 26, 157–178 (2016).

Costa, H. Pork Barrel as a Signaling Tool: The Case of US Environmental Policy Working Paper No. 255 (Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, 2016).

Primo, D. M. & Snyder, J. M. Party strength, the personal vote, and government spending. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 54, 354–370 (2010).

Lazarus, R. J. Super wicked problems and climate change: restraining the present to liberate the future. Cornell Law Rev. 94, 1153–1233 (2009).

Marsiliani, L. & Renstrom, T. I. Time inconsistency in environmental policy: tax earmarking as a commitment solution. Econ. J. 110, C123–C138 (2000).

Aklin, M. & Urpelainen, J. Political competition, path dependence, and the strategy of sustainable energy transitions. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 57, 643–658 (2013).

Rothstein, B. Just Institutions Matter: The Moral and Political Logic of the Universal Welfare State 153 (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1998).

Boyce, J. Carbon Dividends: The Bipartisan Key to Climate Policy? (INET Economics, 2017); https://go.nature.com/2tBRE6A

Gilens, M. Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy (Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 2009).

Auctioning (European Commission, 2018); https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/auctioning_en

Burtraw, D. & Sekar, S. Two world views on carbon revenues. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 4, 110–120 (2014).

Edenhofer, O., Flachsland, C., Jakob, M. & Lessman, K. in The Oxford Handbook of the Macroeconomics of Global Warming (eds Bernard, L. & Semmler, W.) 261–297 (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2015).

Koch, N., Grosjean, G., Fuss, S. & Edenhofer, O. Politics matters: Regulatory events as catalysts for price formation under cap-and-trade. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 78, 121–139 (2016).

Soile, I. & Mu, X. Who benefit most from fuel subsidies? Evidence from Nigeria. Energy Policy 87, 314–324 (2015).

State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2016 (World Bank, Ecofys & Vivid Economics, 2016).

Schwab, K. The Global Competitiveness Report 2012–2013: Full Data Edition (World Economics Forum, 2012).

Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International, 2017).

Carbon Levy and Rebates (Government of Alberta, 2018); https://www.alberta.ca/climate-carbon-pricing.aspx

Jotzo, F. Australia’s carbon price. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 475–476 (2012).

Budget and Fiscal Plan 2016/17–2018/19 (British Columbia Ministry of Finance); https://go.nature.com/2KmRQ3R

Beck, M., Rivers, N., Wigle, R. & Yonezawa, H. Carbon tax and revenue recycling: Impacts on households in British Columbia. Resour. Energy Econ. 41, 40–69 (2015).

Carl, J. & Fedor, D. Tracking global carbon revenues: A survey of carbon taxes versus cap-and-trade in the real world. Energy Policy 96, 50–77 (2016).

CO 2 Levy (FOEN, 2017); https://go.nature.com/2MU6o8G

Carbon tax: a timeline of its tortuous history in Australia. ABC News (17 July 2014); https://go.nature.com/2N1xP1q

Dreyer, S. J., Walker, I., McCoy, S. K. & Teisl, M. F. Australians’ views on carbon pricing before and after the 2013 federal election. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1064–1067 (2015).

Harrison, K. The Political Economy of British Columbia’s Carbon Tax Environment Working Paper No. 63 (OECD, 2013).

Murray, B. & Rivers, N. British Columbia’s revenue-neutral carbon tax: a review of the latest ‘grand experiment’ in environmental policy. Energy Policy 86, 674–683 (2015).

Baranzini, A., Thalmann, P. & Gonseth, C. in Voluntary Approaches in Climate Policy (eds Barranzini, A. & Thalman, P.) 249–277 (Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2004).

Thalmann, P. The public acceptance of green taxes: 2 million voters express their opinion. Public Choice 119, 179–217 (2004).

Gebhart, T. Direct Democracy and Environmental Policy [in German] (Deutscher Universitäts, Wiesbaden, 2002).

Évaluations des Voies et Moyens - Annexe au Projet de Loi de Finances Pour 2018 (French Government, 2018); https://go.nature.com/2lyTem7

Perthuis, C. de & Faure, A. Hausse de la taxe carbone: quels impacts sur le porte-monnaie? The Conversation (8 January 2018); https://go.nature.com/2tEjDCv

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Carattini, M. Carvalho, I. Dorband, C. Flachsland, M. Jakob, F. Jotzo, L. Osberg, J. Pless, A. Skarbek and C. Touzet for helpful discussions. We further thank M. Roesti, J. Schiele and S. Sulikova for research assistance. We thank participants of a symposium for the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, seminar audiences in Berlin, Gothenburg and Oxford and attendees of the 23rd annual conference of the European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists for useful comments. L. M. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). C.H. acknowledges support from the Oxford Martin Programme on the Post-Carbon Transition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

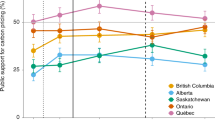

Emmanuel Combet, David Klenert and Linus Mattauch jointly conceived the study. Its design was further refined through inputs from Cameron Hepburn and Ryan Rafaty. David Klenert coordinated the writing process and wrote large parts of the manuscript with inputs from Emmanuel Combet, Cameron Hepburn, Linus Mattauch and Ryan Rafaty. Ryan Rafaty is responsible for writing the section on political science and for creating Fig. 1. David Klenert and Linus Mattauch jointly wrote the behavioral science and public economics sections. Ottmar Edenhofer and Nicholas Stern provided crucial feedback on the manuscript at different stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.R. is employed as a researcher at Climate Leadership Council, a non-governmental organization promoting a proposal for a national US carbon tax with revenues allocated as per-capita lump-sum dividends. This employment commenced five months after he joined as a co-author.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary notes 1-2, Supplementary tables 1-2, Supplementary references

Supplementary Data 1

A more extensive summary of publicly available data on real-world carbon pricing revenue recycling

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klenert, D., Mattauch, L., Combet, E. et al. Making carbon pricing work for citizens. Nature Clim Change 8, 669–677 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0201-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0201-2

This article is cited by

-

Designing a circular carbon and plastics economy for a sustainable future

Nature (2024)

-

The impacts of decarbonization pathways on Sustainable Development Goals in the European Union

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Political strategies for climate and environmental solutions

Nature Sustainability (2023)

-

Psychological inoculation strategies to fight climate disinformation across 12 countries

Nature Human Behaviour (2023)

-

Emission pathways and mitigation options for achieving consumption-based climate targets in Sweden

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)